Arrack

Two kinds of Arrack from Sri Lanka | |

| Type | Alcoholic drink |

|---|---|

Arrack, also spelt arak,[1] is a distilled alcoholic drink typically produced in the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia, made from either the fermented sap of coconut flowers, sugarcane, grain (e.g. red rice) or fruit, depending upon the country of origin. The clear distillate may be blended, aged in wooden barrels, or repeatedly distilled and filtered depending upon the taste and color objectives of the manufacturer. Arrack is not to be confused with arak, an anise-flavored alcoholic beverage traditionally consumed in Eastern Mediterranean and North African countries.

Etymology

The word derived from the Arabic word arak (عرق, arq), meaning 'distillate'. In the Middle East and Near East, the term arak is usually used for liquor distilled from grapes and flavored with anise.

Unlike arak, the word arrack has been considered by some experts to be derived from areca nut, a palm seed originating in India from the areca tree and used as the basis for many varieties of arrack. In 1838, Samuel Morewood's work on the histories of liquors was published. On the topic of arrack, he said:

| “ | The word arrack is decided by philologers to be of Indian origin; and should the conjecture be correct, that it is derived from the areca-nut, or the arrack-tree, as Kaempfer calls it, it is clear, that as a spirit was extracted from that fruit, the name was given to all liquors having similar intoxicating effects. The term arrack being common in eastern countries where the arts of civilized life have been so early cultivated, it is more reasonable to suppose that the Tartars received this word through their eastern connections with the Chinese, or other oriental nations, than to attribute it to a derivation foreign to their language, or as a generic term of their own. The great source of all Indian literature, and the parent of almost every oriental dialect, is the Sanskrit, a language of the most venerable and unfathomable antiquity, though now confined to the libraries of the Brahmins, and solely appropriated to religious laws and records. Mr. Halhed, in the preface to his Grammar of the Bengal language, says, that he was astonished to find a strong similitude between the Persian, Arabian, and even the Latin and Greek languages, not merely in technical and metaphorical terms, which the mutation of refined arts or improved manners might have incidentally introduced, but in the very groundwork of language in monosyllables in the names of numbers, and the appellations which would be first employed on the immediate dawn of civilisation. Telinga is a dialect of the Sanskrit, in which the word areca is found, it is used by the Brahmins in writing Sanskrit, and since to the latter all the other tongues of India are more or less indebted, the term areca, or arrack, may be fairly traced through the different languages of the East, so that the general use and application of this word in Asiatic countries cannot appear strange. To these considerations may be added, that in Malabar the tree which yields the material from which this oriental beverage is produced is termed areca, and, among the Tungusians, Calmucks, Kirghizes, and other hordes, koumiss, in its ardent state, is known by the general term, "Arrack or Rak." Klaproth says that the Ossetians, (anciently Alans,) a Caucasian people, applied the word " Arak" to denote all distilled liquors, a decided confirmation of the foregoing observations and opinions.[2] | ” |

Regardless of the exact origin, arrack has come to symbolize a multitude of largely unrelated, distilled alcohols produced throughout Asia and the eastern Mediterranean. This is largely due to the proliferation of distillation knowledge throughout the Middle East during the 14th century. Each country named its own alcohol by using various Latin alphabet forms of the same word which was synonymous with distillation at the time (arak, araka, araki, ariki, arrack, arack, raki, raque, racque, rac, rak).[3]

Arrack in different countries

India

Arrack was banned in the states of Kerala in 1996,[4] and Karnataka on 1 July 2007.[5][6]

-stokerij_Maatschappij_'Aparak'_Batavia'_TMnr_10014126.jpg)

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the term arak is widely used to describe the arrack. Arak (or rice wine) was a popular alcoholic beverage during the colonial era.[7] It is considered the "rum" of Indonesia, because like rum, it is distilled from sugarcane. It is a pot still distillation. To start the fermentation, local fermented red rice is combined with local yeast to give a unique flavor and smell of the distillate. It is distilled to approx. 70% ABV. Like rum, Batavia-arrack is often a blend of different original parcels.

One of the longest established arak company in Indonesia is the Batavia Arak Company (Dutch Batavia-Arak Maatschappij), which was already in business by 1872, became a limited liability company in 1901, and was still operating in the early 1950s. The Batavia Arak Company also exported arak to the Netherlands and had an office in Amsterdam. Some of the arrack brand produced by Batavia Arak Company were KWT (produced in the Bandengan (Kampung Baru) area of old Jakarta) and OGL.[7]

Batavia-Arrack is said to enhance the flavor when used as a component in other products, as in the herbal and bitter liqueurs. It is used as a component in liqueurs (like the punsch), pastries (like the Scandinavian Runeberg torte or the Dresdner Stollen), and also in the confectionery and flavor industries.

In Indonesia, arrack is often created as a form of moonshine. Such illicit production may result in methanol-tainted arrack that can lead to death.[8][9]

Philippines

The Filipino term for wine (and by extension alcoholic beverages in general) is alak, derived from the Arabic word "arrak". The term "arak," though, is specifically used in Ilocano.

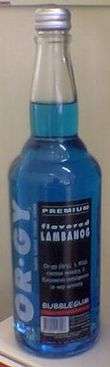

Lambanóg is commonly described as coconut wine or coconut vodka. Distilled from the sap of the unopened coconut flower, it is particularly potent, having a typical alcohol content of 80 to 90 proof (40 to 45%) after a single distillation; this may go as high as 166 proof (83%) after the second distillation. As with coconut arrack, the process begins with the sap from the coconut flower. The sap is harvested into bamboo receptacles similar to rubber tapping, then cooked or fermented to produce a coconut toddy called tubà. The tubà, which by itself is also a popular beverage, is further distilled to produce lambanóg.

Until recently, lambanóg was considered a local analogue to moonshine and other home-brewed alcoholic drinks due to the process's long history as a cottage industry. Though usually served pure, it is traditionally flavoured with raisins, but lambanóg has recently been marketed in several flavours such as mango, blueberry, pineapple, bubblegum and cinnamon in an effort to appeal to all age groups.[10]

Quezon province is the major producer of lambanog wine in the Philippines because of the abundance of coconut plantations in the area. The Lambanog originated and first distilled in Tayabas in Quezon, a Spanish soldier named Alandy established the first distilling business, which has come down to the present generation as Mallari Distillery. The three main distilleries in the country are also located in Tayabas City - the Mallari Distillery, the Buncayo Distillery, and the Capistrano Distillery (Vito, 2004).[11]

The Italian explorer, Antonio Pigafetta, stated that the arrack that he drank in Palawan and nearby islands in 1521 was made from distilled rice wine.[12]

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is the largest producer of coconut arrack and up until 1992 the government played a significant role in its production.[13][14]

Other than water, the entire manufacturing process revolves around the fermentation and distillation of a single ingredient, the sap of unopened flowers from a coconut palm (Cocos nucifera).[15] Each morning at dawn, men known as toddy tappers move among the tops of coconut trees using connecting ropes not unlike tightropes. A single tree may contribute up to two litres per day.

Due to its concentrated sugar and yeast content, the captured liquid naturally and immediately ferments into a mildly alcoholic drink called "toddy", tuak, or occasionally "palm wine". Within a few hours after collection, the toddy is poured into large wooden vats, called "wash backs", made from the wood of teak or Berrya cordifolia. The natural fermentation process is allowed to continue in the wash backs until the alcohol content reaches 5-7% and deemed ready for distillation.

Distillation is generally a two-step process involving either pot stills, continuous stills, or a combination of both. The first step results in "low wine", a liquid with an alcohol content between 20 and 40%.[16] The second step results in the final distillate with an alcohol content of 60 to 90%. It is generally distilled to between 33% and 50% alcohol by volume (ABV) or 66 to 100 proof. The entire distillation process is completed within 24 hours. Various blends of coconut arrack diverge in processing, yet the extracted spirit may also be sold raw, repeatedly distilled or filtered, or transferred back into halmilla vats for maturing up to 15 years, depending on flavor, color and fragrance requirements.

Premium blends of arrack add no other ingredients, while the inexpensive and common blends are mixed with neutral spirits before bottling. Most people describe the taste as resembling "…a blend between whiskey and rum", similar, but distinctively different at the same time.

Coconut arrack is traditionally consumed by itself or with ginger beer, a popular soda in Sri Lanka. It also may be mixed in cocktails as a substitute for the required portions of either rum or whiskey. Arrack is often combined with popular mixers such as cola, soda water, and lime juice.

Production types

According to the Alcohol and Drug Information Centre's 2008 report on alcohol in Sri Lanka, the types of arrack are:[17]

- Special arrack, which is produced in the highest volume, nearly doubling in production between 2002 and 2007.

- Molasses arrack is the least-processed kind and considered the common kind.[17] Nevertheless, as a whole, arrack is the most popular local alcoholic beverage consumed in Sri Lanka and produced as a wide variety of brands that fit into the following three categories:

- Premium aged, after distillation, is aged in halmilla vats for up to 15 years to mature and mellow the raw spirit before blending. Premium brands include Ceylon Arrack, VSOA, VX, Vat9, Old Reserve and Extra Special.

- Premium clear is generally not aged, but often distilled and/or filtered multiple times to soften its taste. Premium clear brands include Double Distilled and Blue Label.

- Common is blended with other alcohols produced from molasses or mixed with neutral spirits as filler.

Producers

Sri Lanka's largest manufacturers, listed in order based on their 2007 annual production of arrack,[17] are:

- DCSL (Distilleries Company of Sri Lanka), 37.25 million litres

- IDL (International Distilleries Ltd), 3.97 million litres

- Rockland Distilleries (Pvt) Ltd, 2.18 million litres

- Mendis, 0.86 million litres

Ceylon Arrack, a brand of Sri Lankan coconut arrack, was recently launched in the UK in 2010. It is also available in France and Germany.[18] White Lion VSOA entered the American market soon after.[19]

St Helena

Historically Arrack has been a common beverage on the island of St Helena, This is likely due to influences of the East India Company, which controlled St Helena and used it as a halfway point between India and England.

Sweden

In Sweden arrak is made into punsch by mixing it with other ingredients. The alcohol content is normally not over 25%, although it has a high sugar content of nearly 30%. The original recipe was a mixture of arrak, sugar, lemon water, water and tea and/or spices. Today punsch is mostly drunk warm as an accompaniment to yellow split pea soup, although it's also used as a flavouring in several types pastries and sweets as well. The name arrak is still retained for some pastries, for example arraksboll, whereas punsch is used for things like punschrulle.

See also

- Feni (Urrack)

- Arak

- List of Indonesian beverages

References

- ↑ Dobbin 1996, p. 54.

- ↑ Morewood, Samuel. A philosophical and statistical history of the inventions and customes of ancient and modern nations in the manufacture and use of inebriating liquors, W. Curry, jun. and company, and W. Carson, 1834, p140.

- ↑ Lopez 1990, p. 109.

- ↑ Arrack ban to stay in Kerala

- ↑ Arrack ban in Karnataka from tomorrow - Economic Times

- ↑ Siddu wants cheap, safe liquor for poor

- 1 2 Merrillees 2015, p. 82.

- ↑ More alcohol deaths in Indonesia, June 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8079531.stm

- ↑ Newcastle nurse poisoned by methanol, October 2011, http://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2011/10/12/3337722.htm

- ↑ Lambanog: a Philippine drink, TED Case Studies #782, 2005

- ↑ , STATUS AND STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS OF THE LAMBANOG WINE PROCESSING INDUSTRY IN LILIW, LAGUNA, PHILIPPINES 2010

- ↑ The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898 (Volume XXXIII, 1519–1522)

- ↑ "Distilleries Company - 'One of the World's Greatest Privatisation Stories'". The Island. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ SL’s Sin Industry and Sin Tax, W. A. Wijewardena Daily Ft ThinkWorth, Accessed 2015-10-11

- ↑ Gunawardena, Charles A. (2005). Encyclopedia of Sri Lanka. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9781932705485.

- ↑ "Arrack for Dummy's". Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 "The Alcohol and Drug information Centre" (PDF). ALCOHOL INDUSTRY PROFILE 2008: AN INSIGHT TO THE ALCOHOL INDUSTRY IN SRI LANKA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Ceylon Arrack Bottled in UK Archived March 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 September 2009

- ↑ "Arrack coming soon to US". Retrieved 17 October 2010.

External links

Cited works

- Dobbin, Christine E. (1996). Asian entrepreneurial minorities: conjoint communities in the making of the world-economy 1570-1940. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7007-0404-0.

- Lopez, Robert S. (1990). Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World. United States: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12357-0.

- Merrillees, Scott (2015). Jakarta: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980. Jakarta: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 9786028397308.

|

| This article is part of the series |

| Indian cuisine |

|---|

|

Regional cuisines

|

|

Ingredients, types of food |

|

See also

|

|