Wind River Indian Reservation

| Wind River Indian Reservation | |

|---|---|

| Indian reservation | |

| |

| Coordinates: 43°16′51″N 108°48′55″W / 43.28083°N 108.81528°WCoordinates: 43°16′51″N 108°48′55″W / 43.28083°N 108.81528°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| Population (2010) | 26,490 |

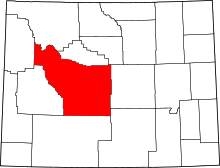

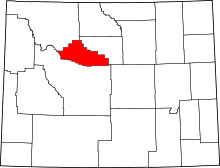

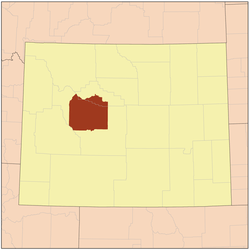

Wind River Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation, located in the central-western portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming, where Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Native American tribes currently live. It is the seventh-largest Indian reservation by area in the United States, encompassing a land area of 3,473.272 sq mi (8,995.733 km²), or land and water area of 3,532.010 sq mi (9,147.864 km²), and the fifth-largest[1] American Indian reservation by population. The reservation constitutes just over one-third of Fremont County and over one-fifth of Hot Springs County.[2]

The reservation is located in the Wind River Basin and is surrounded by the Wind River Mountain Range, Owl Creek Mountains, and the Absaroka Mountains. The 2000 census reported the population of Fremont County as 40,237 inhabitants. According to the 2010 census,[3] only 26,490 people now live on the Reservation. Tribal headquarters are located at Fort Washakie. The Shoshone Rose Casino (Eastern Shoshone) and the Wind River Casino, Little Wind Casino, and 789 Smoke Shop & Casino (all Northern Arapaho) are the only casinos in Wyoming.

History

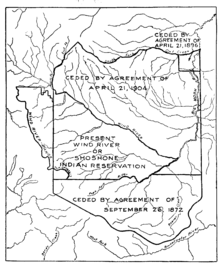

The Wind River Indian Reservation was established by the United States for the Eastern Shoshone Indians in 1868, restricting them from their formerly vast territory. Camp Augur, a military post with troops, was established at the present site of Lander on June 28, 1869. In 1870 the name was changed to Camp Brown and in 1871, the post was moved to the current site of Fort Washakie. The name was changed to honor the Shoshone Chief Washakie in 1878 and the fort continued to serve as a military post until the US abandoned it in 1909.[4] By that time, a community had developed around the fort. Sacagawea, a woman guide with the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806, was later interred here. Her son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, who was a child on the expedition, has a memorial stone in Fort Washakie but was interred in Danner, Oregon.

A government school and hospital operated for many years east of Fort Washakie; Arapaho children were sent here to board during the school year. St. Michael's at Ethete was constructed in 1917–1920. The village of Arapahoe was originally established as a US sub-agency to distribute rations to the Arapaho. At one time it also operated a large trading post. In 1906 a portion of the reservation was ceded to white settlement and Riverton developed on some of this land. Under the Dawes Act, communal land was allotted to individual households. Many Arapaho names were anglicized at the time. Irrigation was constructed to support farming and ranching in the arid region. The Arapaho constructed a flour mill near Fort Washakie.[4]

Mid-20th century to present

Of the population in 2011, 3,737 were Shoshone and 8,177 were Arapaho. 1,880,000 acres of Tribal Land with 180,387 acres of Wilderness area,[5][6] compared to the population in 2000, 6,728 (28.9%) were Native Americans (full or part) and of them 54% were Arapaho and 30% Shoshone. Of the Native American population, 22% spoke a language other than English at home.

Major Crime on the Reservation

A study conducted titled, Delinquency Among Wind River Indian Reservation Youth, showed that large amounts of the Reservation's youth were charged with a variety of crimes. This study shows that from the years 1967-1971, 1,047 juvenile cases were examined by the Court of Indian Offenses on the Reservation. A large majority, 693, of the 1,047 cases dealt with delinquency, with 470 of these cases involving a young male defendant. The distribution of juvenile charges showed that 251 of 917 total charges involved alcohol-related crimes (public intoxication, minor in possession, and driving under the influence).[6]

In 2009, three young Native American girls (13, 14, and 15 years of age) were murdered on the Reservation. They were found in the bedroom of a small home in Beaver Creek, which is a low-income tribal housing community. They had overdosed on methadone, a painkiller which is used to wean heroin addicts off of heroin. However, no one knows how they received the painkillers, which is why the coroner ruled their deaths homicides. The Reservation has a very thin police force, which led to the FBI being the lead investigators on the homicide. The Reservation has six officers who are responsible for patrolling an area about the size of Rhode Island. Two teenage boys were arrested in connection with the girls' deaths. One boy had given them his grandmother's methadone, saying that the girls were already high and he wanted to help them, because they didn't want to go home and have their parents see them.[7]

In the early 21st century, the media reported severe problems of reservation poverty and unemployment, resulting in associated crime and a high rate of drug abuse.[9] In 2012, the New York Times released an article titled, "Brutal Crimes Grip an Indian Reservation". According to this article, written by Timothy Williams, an Iraq war strategy, "the surge", was used to attempt to fight crime taking hundreds of officers from the National Park Service and other federal agencies. This had major success at other reservations, but on the Wind River Indian Reservation, violent crime increased by seven percent. In 2013, Business Insider produced a photo scrapbook and indicated locals refer to different streets by infamously violent American locations such as Compton near Los Angeles.[8]

The reservation was experiencing a methamphetamine crisis that has since been significantly reduced, even while addiction continues to be a problem. Other residents say the Wind River Indian Reservation is a more hopeful place than is often portrayed in press reports.[7]

Issues on the Reservation

Health

There are only two outpatient clinics located on the reservation. There is one located in Arapahoe and the second one is located in Ft. Washakie. The clinics offer a variety of services such as Behavioral Health, Social Services, Business Office, Community Health Nursing, Purchased/Referred Care (PRC), Dental, Diabetes Program, Laboratory/Radiology, Medical Records, Medical Services, Nursing, Optometry, Office of Environmental Health, Utilization Review and Compliance.[9] The average life expectancy for someone living on the reservation is 49 years old.[10]

According to A Suicide Epidemic in an American Indian Community, a study done regarding suicide on the Reservation in 1985, the months of August and September produced very high suicide numbers. There were 12 reported deaths, and 88 additional verified instances of suicide threats or suicidal attempts. This epidemic is nothing new to Native American tribes which can be attributed to high unemployment and extensive abuse of alcohol. 40 of the attempts were between the ages of 13-19, and 24 attempts were between the ages of 20-29. Of the 88 attempts, alcohol was involved in 47 cases, with 46 male and 42 females attempting suicide. Many events were created to attempt to stop this suicide epidemic that hit the Reservation. Parents, and elder community members, closed Bingo nights for children recreational activities instead. The schools extended hours for learning centers and gymnasiums time. An alcohol treatment program began holding weekly alcohol-free teen dances, which were very popular and had a high attendance. These initiatives were designed to provide a safe, and alcohol-free, environment for the children and young adults. This ultimately helped the epidemic, and prevent suicide attempts across such young age groups.[11]

Another issue affecting the reservation is alcoholism. An article published in 2001, The Social Construction of American Indian Drinking: Perceptions of American Indian and White Officials, discovered, by interviewing 12 Native Americans residing on the Reservation and 12 Whites who also reside on the Reservation, that alcoholism is present and thriving on the Reservation. 10 of 12 Natives have said that alcohol is a problem shared by both minors and adults, while all 12 Whites have said this. 10 of 12 American Indians said that alcohol is strongly linked to crime, while 11 of 12 Whites have agreed. The biggest outlier was that only 8 of 12 American Indians have said that alcohol is a very serious problem on the Reservation, while 11 of 12 Whites have said the same.[11] In an article in Casper Startribune, of the 79 deaths from 2004, a quarter of the deaths were attributed to alcoholic cirrhosis and half of the deaths were related to alcoholic deaths due to car crashes and homicide killing connected to drugs. According to Cathy Keene, local director for Indian Health Services, the reservation's situation has gotten to the point where the Public Health Service can only fund things that require emergency care.[12] The lack of funding has resulted in less surgeries and medical procedures. The Ft. Washakie Health Center is only working with slightly more than half of its needed funding according to Richard Brannan, chief executive officer of the Indian Health Service.[13]

Approximately 71% of the population is obese and 12% have diabetes, compared to the National average 36.5% and 9.4%. In 2009, the reservation received a five-year grant in funding from the Merck Foundation Alliance's for Reducing Diabetes Disparities (ARDD) to improve patient care, community clinical system of care, and clinicians.[14] The ultimate goal of the funding is to find an ideal model or solution that can be repeated at other reservations to decrease the rate of diabetes. After receiving funding, the project team gathered other members who shared an interest in preventing and managing diabetes on the reservation. They recruited members of the Wind Reservation Coalition for Diabetes Management and Prevention, Wind River Indian Health Service, Fremont County Public Health, The University of Wyoming's Centsible Nutrition Program, Sundance Research Institute, and the State of Wyoming Department of Health's Diabetes Prevention program. These members help create focus groups consisting of residents from the reservation to understand the barriers and the issues with the health services. The group created a disease management program based on the Chronic Care Model which focused on looking at members with or at risk of diabetes views on diabetes. They created specific exercises and nutrition programs that took in account of the lifestyle and culture of the residents. For individuals that were already diagnosed, the program created a self-management education program. After the 5 year program, the results showed improved clinical outcomes. 47% of the participants saw a decrease in their HbA1c levels, improved diabetes management with a mean decrease of 1.12 points. Due to the success of the program, a two-year grant from the AstraZeneca Foundation proposed to help 350 reservation residents who are at risk for cardiovascular disease.[15]

Education

Only 60% of Native Americans complete high school, compared to 80 percent of the White students who graduate high school. The Wind River reservation dropout rate is 40 percent more than twice the state average of Wyoming. Teenagers are twice as likely to commit suicide compared to other young adults within Wyoming.[10] There are other issues that commonly occur on the reservation such as child abuse, teenage pregnancy, sexual assault, and domestic violence are endemic, and alcoholism are common problems within the reservation. There was the death of an eighth grader at Wyoming Indian Middle School who was killed by voluntary manslaughter in April 2010. Wind River's crime rate is 5-7 times the national average, and has a long history of gang violence.[10] The Wind River Indian Reservation have struggled with an alarming percent of unemployment. According to a 2005 Bureau of Indian Affairs report, the Northern Arapaho Tribe's unemployment rate was 73 percent and Eastern Shoshone's was 84 percent.[16] Sadly, the employment situation on the Wind River reservation is not at all atypical. Other reservations have similar or even higher rates of unemployment. There does seem to be a consensus on what some of the contributing factors are. One example is lack of adequate physical infrastructure—good roads and bridges, public water supply and sanitation facilities, and adequate education. The Wyoming Department of Education decided to collaborate with the North Central Comprehensive Center in order to improve the reservations education system. They conducted multiple listening sessions within classes of different schools within the reservations. After the session, both parents and students came to the consensus that the Wind River reservation schools needed more teachers that are Native American. Also, since there are a high percentage of gang violence that occur in Wind River, they also advocated for more security in order to lessen bullying and gangs, and more Native American relevant courses, such as their Native American Language.[17] Lastly, students and parents wanted a standard for academic expectations that should be held within all schools within the reservation. One of the parents remarked "My grandson goes to the school in Lander. We won't transfer him back here to the reservation because they're two years behind where my grandson is." Megan Degenfelder, Wyoming Department of Education Policy Advisor, said the inputs from the listening sessions has the department headed in the right track "to improve education for Native American students and to best be able to allocate our resources and time."[17]

Environmental

According to Folo Akintan's preliminary data, a medical doctor and epidemiologist from Rocky Mountain Tribal Epidemiology Center in Billings, Mont., 4 out of 10 Wind River Reservation residents reported that they have had a relative die from cancer. Many of the residents believe it's due to uranium mill.[19] In 1958 Susquehanna-Western began processing uranium and vanadium ore on the reservation with sulfuric acid. Although the mill closed in 1963, there were tailings left behind. In 1988 the Department of Energy (DOE) found that soils, surface water and shallow groundwater were all contaminated. The DOE believes the land will naturally flush itself and be contamination free 100 years from now.[20] In 2010, the DOE recorded high levels of contaminant. The levels were 100 times higher than what is allowed by the USEPA Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for drinking water.[21] Tribal officials were worried about their water sources being contaminated by these deadly toxins. The DOE placed plastic PVC for the water pipeline. They reassured the residents that it was secure and wouldn't break however the Wind River Environmental Quality Commission official state that the pipe has broken multiple times within the past year. The residents have become fed up with the DOE due to lack of cleaning up the land, poor pipeline equipment, and lack of spreading data about the high levels of contamination from the flood.[20] Although it's hard to suggest that a uranium tailing site is causing an increased cancer rate, Dr. Akintan suggests, "It is a risk indicator". The cancer rates on the reservation are higher than the national and state average. Although Dr. Akintan's reports show an increased cancer rate in the research had many limitations. The first limitation was lack of responses returned back. There was a total of 3,000 surveys and only 286 were completed. Also, the data collected was only self-report data which is unreliable due to response bias from the participants. Also, the results were leading but not statistically significant.[19]

The tribes have re-established populations of big game, such as moose, elk, mule deer, whitetail deer, bighorn sheep and pronghorn antelope, and have passed hunting regulations to conserve these species.[22] In November 2016 the Shoshone introduced ten bison to the reservation, the beginning of what is planned as a 1000-head herd. They were the first bison to be seen on the Wind River Reservation since 1885. Area suited as buffalo habitat is estimated at 700,000 acres on the west side and another 500,000 acres on the north of the reservation.[22]

In popular culture

- PBS aired the documentary film Chiefs, filmed from 2000-2001 by Daniel Junge about the members of the successful high school basketball team on the Wind River Reservation.

- Margaret Coel has written a series of mystery novels set on the Wind River Reservation featuring Arapaho attorney Vicky Holden and Father John O'Malley, pastor of the fictional St. Francis mission. The actual Roman Catholic mission on the reservation is the Saint Stephen's Indian Mission.

- In 2017, the film Wind River was released. Written and directed by Taylor Sheridan, it stars Jeremy Renner, Elizabeth Olsen, Graham Greene and Gil Birmingham. Set in winter, the thriller mystery explores the death of a young Arapaho woman on the reservation and social conditions there. The film was based on true events and shows depictions of sexual assault on reservations.

The Wind River at the Wind River Indian Reservation, Wyoming

The Wind River at the Wind River Indian Reservation, Wyoming Sunset with tepees on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming.

Sunset with tepees on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming. Flag of the Eastern Shoshone tribe

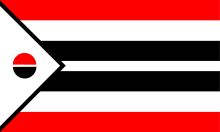

Flag of the Eastern Shoshone tribe Flag of the Northern Arapaho tribe

Flag of the Northern Arapaho tribe

Communities

- Arapahoe

- Boulder Flats

- Crowheart

- Ethete

- Fort Washakie

- Hudson (part, population 72)

- Johnstown

See also

Notes

- ↑ http://www.worldatlas.com/articles/biggest-indian-reservations-in-the-united-states.html

- ↑ 2000 Census, U.S. Census Bureau

- ↑ http://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-publications/Rocky_Mountain_Region.pdf

- 1 2 Eastern Shoshone Tribal Culture

- ↑ "2011/2012 Fishing Regulations, Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes, Wind River Indian Reservation Wyoming" (Press release). Fish and Game Department, Wind River Indian Reservation, Fort Washakie, Wyoming. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- 1 2 "Wind River Fish & Game - Home". Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- 1 2 "The reservation reacts to new, troubling press coverage". WyoFile. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- ↑ AP. "ON ONE RESERVATION, A SUICIDE CRISIS". Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Wind River Service Unit | Healthcare Facilities". Billings Area. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Timothy (2012-02-02). "Brutal Crimes Grip Wind River Indian Reservation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- 1 2 Tower, R.N., M.S., Margene (Summer 1989). "A Suicide Epidemic in an American Indian Community". American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 3 (1): 34–44 – via UCDenver.

- ↑ correspondent, BRODIE FARQUHAR Star-Tribune. "Tribes target health problems". Casper Star-Tribune Online. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Indian Country: Covering Native Health Issues with Sensitivity". Center for Health Journalism. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ "Battling Diabetes on Reservations: A Two-Part Look at Coalitions and Culture - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Wind River Reservation | Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality". www.ahrq.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "UNEMPLOYMENT ON INDIAN RESERVATIONS AT 50 PERCENT: THE URGENT NEED TO CREATE JOBS IN INDIAN COUNTRY" (PDF).

- 1 2 Edwards, Melodie. ""We Need More Native Teachers": Wyoming DOE Hears Input On Reservation Schools". Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ↑ "Greater sage-grouse lek on the Wind River Reservation". Flickr. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- 1 2 "Wind River Indian Reservation study ties cancer to uranium site". WyoFile. 2013-06-25. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- 1 2 "Cancer-Riddled Wind River Reservation Fights EPA Over Uranium Contamination - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ Lewis, Johnnye; Hoover, Joseph; MacKenzie, Debra (2017). "Mining and Environmental Health Disparities in Native American Communities". Current Environmental Health Reports. 4 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1007/s40572-017-0140-5. PMC 5429369. PMID 28447316.

- 1 2 https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/environment/wind-river-reservation-receives-first-bison-since-1885/ Indian Country Today, 31 December 2016

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wind River Indian Reservation. |

- Wind River Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Wyoming United States Census Bureau

- Tetona Dunlap (February 2012). "As elders pass, Wind River Indian Reservation teachers turn to technology to preserve Shoshone language". WyoFile. Retrieved 2012-02-29.