Apollo 15 postal covers incident

The Apollo 15 postal covers incident, a 1972 NASA scandal, involved the astronauts of Apollo 15, who carried about 400 unauthorized postal covers into space and to the Moon's surface on the lunar lander Falcon. Some of the envelopes were sold later at high prices by West German stamp dealer Hermann Sieger, and are known as "Sieger covers". The crew of Apollo 15, David Scott, Alfred Worden and James Irwin, agreed to take payments for carrying the covers; though they returned the money, they were reprimanded by NASA. Amid much press coverage of the incident, the astronauts were called upon to appear before a closed session of a Senate committee and never flew in space again.

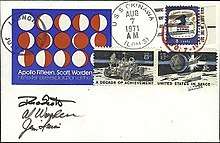

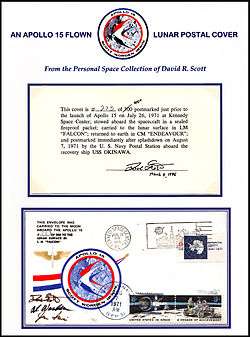

The three astronauts and an acquaintance, Horst Eiermann, had agreed to have the covers made and taken into space. Each astronaut was to receive about $7,000. Scott arranged to have the covers postmarked on the morning of the Apollo 15 launch. They were packaged for space and brought to him as he prepared for liftoff. Apparently due to an error, they were not included on the list of the personal items he was taking into space. These covers spent from July 30 to August 2, 1971, on the Moon inside the Falcon. On August 7, the day of splashdown, the covers were postmarked again on the recovery carrier USS Okinawa. One hundred were sent to Eiermann (and passed on to Sieger); the remaining covers were divided among the astronauts.

Worden had made arrangements to carry 144 additional covers for an acquaintance, F. Herrick Herrick, which he sent to Herrick after the mission. When NASA subsequently heard about the Herrick covers, the astronauts' supervisor, Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton, warned Worden to avoid further commercialization of what he had been allowed to bring into space. After Slayton heard about the Sieger arrangement, he removed the three as backup crew members for Apollo 17, though the astronauts had by then refused compensation from Sieger and Eiermann. The Sieger matter became generally known in June 1972. There was widespread news coverage, with some saying astronauts should not be allowed to reap personal profits from NASA missions.

By 1977, all three former astronauts had left NASA. In 1983, they sued successfully for the return of the covers impounded in 1972, and received them in an out-of-court settlement. One of the covers given to Sieger sold for over $50,000 in 2014.

Background

After the start of the Space Age with the launch of Sputnik I on October 4, 1957, astrophilately (space-related stamp collecting) began. Nations such as the United States and USSR issued commemorative postage stamps depicting spacecraft and satellites. Astrophilately was most popular during the years of the Apollo Program's moon landings from 1969 to 1972.[1]

Collectors and dealers sought philatelic souvenirs related to the American space flight program, often through specially-designed envelopes (known as covers). Cancelling them became a major duty of the employees of the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) post office on space mission launch days.[2] Beginning in the late 1960s, Harold G. Collins, head of the Mission Support Office at KSC[lower-alpha 1] arranged for specially designed envelopes to be printed for the different missions, and to be cancelled on the launch dates.[3] Such unflown philatelic covers were often gifts for the astronauts' friends, or for employees of NASA and its contractors.[4] American astronauts were allowed to take Personal Preference Kits (PPKs) into space with them. These small bags, limited in size and weight, contained personal items the astronauts wanted to be flown as souvenirs of the mission. As the spaceflights moved toward and culminated in the moon landings, the public's fascination with items flown in space increased, as did their value.[5]

Although it was not publicly known until September 1972, 15 of the men who entered space as Apollo Program astronauts, before Apollo 15, had agreed with a West German named Horst Eiermann to autograph 500 philatelic items (postcards and blocks of stamps) in exchange for $2,500. This included a member of each mission between Apollo 7 (1967) and Apollo 13 (1970). These items were not taken into space.[6] Covers were prepared by the crews and flown on Apollo 11, Apollo 13 and Apollo 14. Ed Mitchell, Lunar Module Pilot for Apollo 14, took his to the Moon's surface in a PPK.[7] These were often retained by the astronauts for many years: Apollo 11's Neil Armstrong kept his until he died, and they were not offered for sale until 2018.[8]

The Apollo 15 mission began when the spacecraft blasted off from KSC on July 26, 1971, and ended when the astronauts and the Command Module Endeavour were recovered by the aircraft carrier USS Okinawa on August 7. Onboard Endeavour were Mission Commander David Scott, Command Module Pilot Alfred Worden and Lunar Module Pilot James Irwin. The Lunar Module Falcon, with Scott and Irwin aboard, landed on the Moon on July 30, 1971, and remained there for just under 67 hours. The mission set a number of space records and was the first to use the Lunar Rover, which Scott and Irwin rode to explore the area around the landing site during three periods of extravehicular activity (EVA).[9] On August 2, prior to terminating the final EVA and entering the Lunar Module, Scott used a special postmarking device to cancel a first day cover of two stamps[lower-alpha 2] for the 10th anniversary of Americans entering space, with their designs depicting lunar astronauts and a rover.[lower-alpha 3][10] According to Irwin in his autobiography, in describing his actions to his terrestrial television audience Scott "brought up a subject that would later have fateful consequences for all of us".[11]

Preparation

Eiermann was acquainted with a stamp dealer named Hermann Sieger from Lorch, West Germany.[12] They had met at KSC in about 1970. Sieger conceived the idea for the space-flown covers in early 1971, and communicated it to Eiermann.[13] Convinced there was a market for such covers, Sieger hoped to recruit an Apollo crew through Eiermann, who knew many of the astronauts.[14]

While Scott and his crewmates were completing their training for the mission, a controversy developed within NASA and Congress over some of the souvenir silver medallions that the crew of Apollo 14 had carried to the Moon. The private Franklin Mint, which had supplied the medallions, melted down some of the ones that had been flown. These were mixed with a large quantity of other metal, and commemorative medals were struck from the mass. These were used as a premium to attract people to pay to join the Franklin Mint Collector's Club. The fact that some part of the medals had flown to the Moon was used in the mint's advertisements.[15] Because the Apollo 14 crew had accepted no money, they were not disciplined.[16] Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton, who supervised the astronauts, reduced the number of medallions each member of Apollo 15 could take along by half.[15] Slayton warned the Apollo 15 crew against carrying any items into space that could make money for them or others.[16] In August 1965, Slayton had issued regulations regarding what personal items could be taken into space by astronauts. His policy required that the items be listed, approved, and checked for safety in space if similar items had not already been flown.[17] Each crew member was bound by NASA standards of conduct issued in 1967 forbidding using one's position in a way "which is motivated by or has the appearance of being motivated by private gain for himself or other persons".[18]

Eiermann lived in Cocoa Beach, Florida, at the time of Apollo 15, and was a local representative of Dyna-Therm Corporation, a Los Angeles firm[19] which was a NASA contractor.[20] According to Scott's autobiography, one night several months before launch, Slayton had Scott and the other crew members came to dinner at Eiermann's house; Scott described Eiermann as a longtime friend of Slayton.[21] Worden, in his autobiography, agreed that the crew was invited to dinner there, but described Scott as inviting his crewmates, and did not mention involvement by Slayton.[22] Scott, in his testimony before a congressional committee in 1972, described Eiermann as a "friend of ours at the Cape", someone with whom he had dined and who knew many people at KSC, including a number of the astronauts.[23] Scott also told the committee that he had met Eiermann at a party, rather than through anyone else at NASA,[24] and that the first Slayton knew of the space-flown Sieger covers was in April of 1972, following an inquiry from a member of the public.[25]

At the dinner, Eiermann proposed the astronauts carry 100 special stamp covers, to be flown to the Moon. Worden stated that he and Irwin, who had not previously gone into space, were assured that this was common practice. The astronauts were told the covers would not be sold until some time in the future after the Apollo Program had ended. They would receive $7,000 each. They were informed that other Apollo crews had made and profited from similar agreements. Earlier astronauts had been given free life insurance. This benefit was no longer available by the time of Apollo 15. To ensure their families were provided for given the severe risks and dangers of their profession, the astronauts agreed to the deal, planning to put the payments aside as funds for their children.[26][27] According to Scott, the astronauts also decided the covers would make good gifts and requested an additional 100 for each of them, totaling 400 covers. Scott indicated in his testimony that after discussion with his crewmates, he expected the covers to be a "very private and noncommercial enterprise." He added: "I admit that this is wrong. I understand it very clearly now. But at the time, for some naive and thoughtless reason, I did not understand the significance of it."[28] Irwin had concerns about the deal, but said nothing to avoid friction with his commander.[29] He wrote in his autobiography that the initial meeting with Eiermann took place in May 1971, and that the astronauts met with him twice thereafter.[30]

A further 144 covers were flown pursuant to an understanding between Worden and F. Herrick Herrick of Miami. According to a letter reporting on the incident with the stamps from NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher to the chairman of the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Clinton P. Anderson, Herrick was a friend of the three astronauts and a longtime stamp collector. He had arranged for Worden, also a stamp collector, to buy an album full of stamps and proposed the astronauts take covers into space. These would be split and set aside for some years, and then sold.[31] In his book Worden said that he had been introduced to Herrick at lunch by former race car driver Jim Rathmann,[lower-alpha 4] and that Herrick proposed the cover scheme. Worden recalled he had been unfamiliar with commemorative covers, and Herrick explained, proposing to have the envelopes printed, and they would be divided between the two of them. The astronaut also related in his autobiography his insistence that the covers must be held, unsold and unpublicized, until after the Apollo Program had ended, and he had retired from NASA and the Air Force. "I didn't want to do anything that would embarrass either myself or NASA, and I believed Herrick was as good as his word. It was a huge lapse in judgment on my part to trust this stranger. I was too old to believe in Santa Claus."[32] In his 1972 testimony before the Senate committee, Worden had described Herrick as a friend with whom he had had past dealings, and with whom he discussed the possibility of commemorative covers;[33] according to a 1978 Justice Department report, Herrick advised Worden before the Apollo 15 flight "that taking such souvenirs to the moon would be a wise investment because of their value to stamp collectors".[34]

Creation and spaceflight

.jpg)

Eiermann was supposed to create the cachet for the special covers he had proposed, but time ran short and Scott did it instead. He used the mission patch for Apollo 15, and when he completed it, he gave it to Collins of the Mission Support Office. Collins arranged with the Brevard Printing Company of Cocoa, Florida for the design to be reproduced on both regular and lightweight ones. The company performed the work, and billed Alvin B. Bishop Jr. in the sum of $156 for the lightweight envelopes and $209 for the regular ones.[35] Bishop, a public relations executive who specialized in the aerospace industry, and who knew many astronauts, created specially-designed covers for a number of the Apollo missions, which he only supplied to the crew and their families.[26] Approximately 3,400 regular envelopes were delivered by the printers, as were between about 1,200 and 1,500 lightweight ones. About a third of the lightweight envelopes were given the additional inscription, "This envelope was carried to the Moon aboard Apollo 15".[35]

Worden recalled that Herrick arranged for a commercial artist, with whom the astronaut had a discussion, and Herrick sent Worden 100 envelopes depicting the phases of the Moon. The astronaut also had in his possession 44 first day covers. Worden added the 144 envelopes to the items he planned to put in his PPK, and listed them for Slayton's approval.[36][37] The 100 Herrick envelopes, along with card inserts stating that the accompanying cover had been carried on Apollo 15, were printed by Ad-Pro Graphics, Inc. of Miami at an expense to Herrick of $50.50; Herrick also obtained the postage stamps for the covers, and two rubber stamps stating the dates of launching and splashdown.[38] Additionally, Worden carried a cover honoring the Wright Brothers. Irwin carried 89 covers, one with a "flown-to-the-Moon" theme, eight with an Apollo 15 design, and 80 covers honoring Apollo 12, carried as a favor for Barbara Gordon, wife of Apollo 12 astronaut Dick Gordon.[39] Barbara Gordon, a stamp collector, had wanted her husband to take the 80 covers on his lunar mission, but he had refused.[40] The eight Irwin Apollo 15 envelopes were apparently supplied by the Kennedy Space Center Philatelic Society.[41] Apollo 15 also carried the cover from the Postal Service to be cancelled on the surface of the Moon, and a backup. All except the 400 had been approved by Slayton,[42] who stated in his testimony that he would almost certainly have approved them if asked, (assuming that their weight could be negotiated with the Flight Director) on condition they remained in the Command Module, and did not go to the lunar surface.[43] In July 1972, after the story broke, William Hines of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that "the idea that this complicated caper could have been carried out without the knowledge and at least tacit permission of Slayton is regarded by people familiar with NASA as ludicrous. Slayton's tight rein over his sometimes fractious charges is legendary."[44]

The crew bought several hundred of the ten-cent First Man on the Moon postage stamp issue,[lower-alpha 5][4] which were affixed to the lightweight Sieger envelopes by the secretaries in the Astronaut Office.[45] Collins had made arrangements with the KSC post office for it to open at 1 am on the launch day—opening so early being not unusual for that facility on an Apollo launch morning—and brought several hundred of the stamped covers. Once the envelopes had been run through the cancellation machine, he took them to the astronaut quarters, where members of the Flight Crew Support Team vacuum sealed them in non-flammable material.[46] Normally, if the Flight Crew Support Team found that an item was not on an astronaut's PPK list, they would add it, but James L. Smotherman, head of the team, stated that "I goofed". Smotherman explained that he had confused the 400 covers with the Herrick covers, which had been approved by Slayton.[47] Scott stated, "I never intended to bootleg the covers. If I had intended to bootleg the covers, I certainly would not have allowed Mr. Collins to handle them or the rest of the people to assist me."[47] Like other items being placed in the pockets on Scott's space suit (for example, his sunglasses), they were first shown to him by the suit technicians helping him dress.[48] Divided into two packets, the bundled covers were about 2 inches (51 mm) thick and weighed about 30 ounces (850 g); they entered the spacecraft in Scott's pockets.[46] Apollo 15 blasted off for the Moon at 9:34 am on July 26, 1971, with three astronauts and about 632 covers aboard.[9][48][49]

At some point while the mission was en route to the Moon, the 400 covers were moved into the lunar lander Falcon; in his testimony, Scott agreed this violated the rules. He stated that he did not recall how it was the transfer took place, and that he was only certain that the envelopes went to the lunar surface because they were in the bag of items taken out of the Falcon in preparation for the return to Earth. Worden stated in his testimony that they were aware of the presence of the covers in the Command Module after the mission's launch, but he did not recall if the covers had been among the many items moved into the Falcon in preparation for the lunar landing; he did not believe the matter had been discussed during the flight.[50] He stated in his autobiography that the night he had agreed to the deal with Eiermann "was the last I heard or thought of about the covers until after the flight ... What arrangements Dave [Scott], Eiermann, and Sieger made to get the covers onto the flight, I never knew until later. Dave later told a congressional committee that he had placed them in a pocket of his spacesuit, but he never shared that information with me".[51] He indicated that the covers he had arranged to have on board, including those from Herrick, remained in his PPK in the Command Module throughout the flight.[52] The testimony before Congress, from multiple individuals including Apollo 15 astronauts, was that the carrying of the covers did not interfere with the mission in any way.[53]

[Irwin:] No!

[Worden:] Good. Very good.

[Scott:] Okay?

[Worden:] Yes. You got to – yes. We've already signed those, haven't we? We haven't signed these? It really doesn't make much difference, does it?

[Scott:] No.

[Worden:] We don't really have to sign them now I guess. We can do that anytime.

[Worden (continuing):] Yes, those – those covers would have been infinitely more valuable, I think.

[Scott:] Oh, well.

[Worden:] Maybe, Dave, it's just as well we didn't.

NASA, Apollo 15 Command Module Onboard Voice Transcription, p. 267. August 3, 1971, 1:56:11 pm through 1:57:21 pm EDT (mission time 196:22:11 through 196:23:21), aboard Endeavour in lunar orbit above the far side of the Moon

Apollo 15 splashed down about 335 miles (539 km) north of Honolulu at 4:46 pm EDT on August 7, 1971; the crew was retrieved by helicopters from the Okinawa.[9] Scott had asked that a supply of the twin space stamps of the design he had cancelled on the Moon (issued August 2) be available on the Okinawa, and on July 14, Forrest J. Rhodes, who ran the postal facility at KSC wrote to the Chief Petty Officer in charge of the Okinawa's post office. The ship replied on the 20th, stating that the stamps could be obtained in time.[54] The stamps were secured from the post office at Pearl Harbor,[55] and were reportedly flown to the Okinawa at sea in the custody of a naval officer.[56] The astronauts had the assistance of Okinawa crew members in affixing the stamps to the 400 covers for cancellation by the ship's post office.[55] The Irwin covers were not postmarked, either at liftoff or splashdown.[57] Worden stated in his book that he never saw the Sieger covers until they were on the flight to Houston, but as Scott mentioned he was having them postmarked with the splashdown date, arranged to have that done for the ones he had taken into space. On the flight, the 400 covers were autographed and divided by the three astronauts:[58] Irwin remembered that the signing took several hours.[59]

Worden later expressed his pride in the successful mission to the Moon, "Under Dave's excellent command, we'd really done our jobs, and felt delighted with the way things had turned out. The mission had been what Apollo was truly all about."[60]

Distribution and scandal

On August 31, 1971, C.G. Carsey, a clerk in the Astronaut Office in Houston, typed certifications on 100 of the covers, with the aid of other NASA employees in her office. The certifications stated that the cover had been landed on the Moon aboard the Falcon. She then signed them as a notary public of Texas. The covers carried a handwritten statement signed by Scott and Irwin that the cover had been landed on the Moon on July 30, and Carsey later stated that she intended only to certify that the signatures were genuine.[61] The question of whether Carsey had improperly certified that the covers had been landed on the Moon (something she had no personal knowledge of) was the subject of an investigation by the Texas Attorney General.[62] On September 2, Scott sent the 100 covers by registered mail to Eiermann, who was in Stuttgart, where he had moved.[63] Eiermann turned the covers over to Sieger, and was rewarded with a commission of about $15,000—ten percent of the anticipated proceeds.[64] One of Irwin's covers was given to Rhodes and one to the president of the Kennedy Space Center Philatelic Society; Irwin stated in 1972 that he had retained the other six.[65]

Sieger received the envelopes from Eiermann in late September or early October, and began to market them, selling them at a price of DM 4,850 (about $1,500 at the time), though he allowed some discount for customers who bought more than one. He kept one for himself, and by November had sold the remaining 99.[66] He numbered and signed the backs of the envelopes in the lower left as token of their genuineness.[56]

Worden recalled in his book that he sent 44 covers to Herrick soon after the return from space, the number that had been agreed, but then sent him 60 belonging to himself for safekeeping.[67] He also gave 28 of them to friends.[34] Herrick consigned 70 covers to Robert E. Siegel, a prominent New York dealer. Siegel sold ten covers for a total of $7,900, receiving a commission from Herrick of 25 percent. Herrick sold three himself, at a price of $1,250 and placed several on commission in Europe.[68]

In late October 1971, a potential customer for one of the Herrick covers wrote to NASA to enquire as to its authenticity. On November 5, Slayton responded, stating that NASA could not confirm whether it was genuine. He warned Worden to ensure that his covers would not be further commercialized.[69] Worden wrote an angry letter to Herrick.[70] In June 1972, Herrick instructed Siegel to send 60 covers to Worden in Houston, which he did by registered mail. Until this point, Siegel had assumed the 60 covers belonged to Herrick.[69][71]

Probably before they made an official NASA trip to Europe in November 1971, the Apollo 15 astronauts received and completed the paperwork necessary for them to receive the agreed $7,000 payments, in the form of accounts in a Stuttgart-area bank. According to Scott's testimony, while they were in Europe, they heard that the Sieger covers were being sold commercially. Scott called Eiermann, who promised to look into it. The astronauts indicated that they received the bankbooks in early 1972.[72] Irwin remembered in his autobiography that before their trip to Europe, Scott came to him and said, "Jim, we are in trouble now—they are starting to sell the envelopes over there," and that the covers cast a shadow over their European trip.[73] Scott stated that the crew discussed it among themselves, then decided that the receipt of funds was improper, and in late February returned the bankbooks to Eiermann, who responded that the astronauts should receive something for their efforts. The crew initially agreed to accept albums filled with aerospace-themed stamps for their children, including issues in honor of Apollo 15, but, Scott related, they decided that too was improper and stated they wanted nothing.[74] According to Fletcher in his letter, this final refusal happened in April 1972.[75] Worden remembered, "we did this before NASA asked us anything about a deal with Sieger—before NASA even knew about it".[76]

According to Irwin, "It was amazing that things remained quiet at NASA for as long as they did."[77] On March 11, 1972, Lester Winick, president of a group of collectors of space stamps and covers known as the Space Topics Study Group, sent a letter to NASA's general counsel asking a number of questions about the Sieger covers. The letter was forwarded for a response to Slayton, who casually mentioned it to Irwin in late March; Irwin told him to talk to Scott.[78] Slayton spoke with Worden on the assumption that the covers referred to were among the group of 144, but Worden told him this was not necessarily the case, and that he should talk to Scott. Slayton did talk to Scott in mid-April, just before the launch of Apollo 16, and Scott told him that there had been 400 covers not on the approved list, and that 100 had been given to a friend.[79] In his own autobiography, Slayton stated that he confronted Scott and Worden about what he called a "regular goddamn scandal" just before the liftoff of Apollo 16, "they told me what the deal was, and I got pretty goddamn angry. So I was through with Scott, Worden, and Irwin. After 16 splashed down, I kicked them off the backup crew for 17."[80] One reason for Slayton's anger is that he had defended the astronauts as rumors of the high prices being paid for the covers circulated; according to Andrew Chaikin in his history of the Apollo Program, Slayton "went out on a limb to defend his people".[81] Although Slayton, when he wrote to Winick, sent a copy of his response to the general counsel's office at NASA Headquarters in Washington (which took no action), he did not inform Administrator Fletcher, the Deputy Administrator, George M. Low or his own superior, Christopher C. Kraft of the postage stamp incident or of the disciplinary action he had taken.[lower-alpha 6][82]

In early June 1972, Low heard from a member of his staff of the possibility covers flown on Apollo 15 might have been sold in Europe. He asked Associate Administrator Dale D. Myers to enquire through NASA management channels for information. Low kept Fletcher informed of the situation as it developed. Myers made an interim report to Low on the 16th, but before he could make his final report on the 26th, the story broke with an article in The Washington Sunday Star on June 18. Kraft interviewed Scott on the 23rd. A full investigation by NASA's Inspections Division was ordered by Low on June 29, and on July 10, the three astronauts were reprimanded for poor judgment,[49][83] something that made it extremely unlikely that they would again be selected to fly in space.[84] Richard S. Lewis, in his early history of the Apollo Program, noted that "in the atmosphere of wheeling and dealing that has characterized government agency—industrial contractor relations in the Space Age, the unauthorized freight that the Apollo 15 crew hauled to the moon was a boyish prank. In the rhetoric of space program critics, though, it was branded as exploitation for personal gain of the most costly technological development in history. In the press, the astronauts were treated like fallen angels."[85] Scott, while stating, "we made a mistake in even considering it",[86] felt that the reaction "was turning into a witch-hunt".[87] Worden, though admitting blame for entering into the deal, felt that NASA had not adequately supported him, nor had Scott taken full responsibility for his role.[88] Irwin, who would become an evangelist after leaving the Astronaut Corps, stated that NASA had no choice but to reprimand them, and hoped he could turn the experience to use in his ministry, helping him empathize with others who had erred.[89]

Another story that broke in mid-July was the dispute regarding the sculpture Fallen Astronaut, left behind on the Moon by Scott in tribute to those killed in the American and Soviet space programs; the sculptor was having copies made for public sale, over the astronauts' objection.[90] Having read of these things in the newspapers, and concerned about the appearance of commercialization of Apollo 15, the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences set a hearing for August 3, and called a number of NASA employees, including the astronauts, Slayton, Fletcher and Low before it.[91] Worden remembered that while there were difficult questions asked about the astronauts' conduct, part of the committee's concern was why NASA management allowed another incident to happen so quickly after the Apollo 14 Franklin Mint matter, and how it was that NASA's chain of command permitted allegations against the astronauts to go unreported to senior management.[92] Invoking a rarely-used Senate rule for when testimony might impact the reputation of witnesses or others, Senator Anderson had the meeting closed to the public.[93]

Aftermath

Andrew Chaikin, A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts (1998 edition), pp. 497–498

Worden remembered how Slayton removed him as a backup crew member for Apollo 17, calling him on May 16, 1972, while Worden was on a geology training trip, and telling him to clear out his office at NASA by the following Monday and go back to the Air Force. Worden wanted to stay at NASA even if he could not fly in space, especially once he learned that Low had seen to it enough derogatory matter was put in his fitness report to ensure that the Air Force would never promote him from his rank of colonel. Additionally, he had been long absent from the mainstream military, and the Air Force was having trouble finding a place for him at short notice. After making the rounds of Slayton's higher-ups, he found some sympathy from Myers, who agreed to help him find a new job at NASA, as it proved at Ames Research Center in California, where his skills as a pilot would be useful.[94]

None of the Apollo 15 crew ever flew in space again.[95] Although there were few flights available as the Apollo Program wound down, Scott had aspired to command the American portion of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first joint mission with the Soviet Union.[96] He was instead made a technical adviser on that mission, and retired from the Air Force in 1975, after which he became director of NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, retiring from NASA in October 1977 and entering the private sector. Worden remained at Ames until his 1975 retirement both from the Air Force and NASA, and then entered the private sector.[97][98] Irwin retired in 1972, founding an evangelical group.[99] The covers affair resulted in prejudice in the Air Force against former astronauts (all three Apollo 15 astronauts had served there), deterring Apollo 14's Stu Roosa from returning to the Air Force when he left NASA, and causing him to go into business instead.[100] Although covers had been taken to the lunar surface by Apollo 16's Charles Duke in April 1972, changes to the PPK procedures instituted by NASA meant that none were taken on Apollo 17 that December.[7] Today, astronauts are forbidden by federal regulation from taking philatelic items into space as mementoes.[101]

The remaining covers in the astronauts' control, 298 from the group of 400,[lower-alpha 7] and 61 more from Worden, were held by NASA amid the investigation; Worden stated he surrendered them at Kraft's request on the understanding they would be returned once the investigation was over, but the covers were transferred to the National Archives in August 1973.[102] There was a Justice Department investigation into the covers,[42][103] and in 1978 the department issued a report indicating that while the government might have some claim to the Herrick covers, it probably did not to the others.[104][105] In 1983, the three men sued, and the government agreed to return all the covers.[105] The government felt that it could not successfully defend the lawsuit, and that NASA either authorized the covers to be flown or was aware of them.[106]

An Apollo 15 postal stamped cover that was one of the group of 298 impounded by the government sold at the January 2008 Novaspace auction for US$15,000.[107][108] A Sieger cover sold in 2014 for over $55,000—the auctioneer noted that it was one of only four Sieger covers to come to public sale since the initial distribution.[109] Worden sold many of the returned Herrick covers to pay debts from his unsuccessful 1982 run for Congress.[14] He stated in 2011 when asked where the covers were, "Lord only knows. Some of them sold, some of them are still in a safety deposit box. They're probably all over the world by now."[95] In a 2013 interview with Worden, Slate magazine found that "he’s vexed by lingering inaccuracies in the Wikipedia entry about the incidents. We ask: Why didn’t he get a friend to log in and correct the entries? He responds with a startled pause. 'Is that right? I didn't know you could do that!' "[110]

See also

- Robbins medallions space-flown medallions from the Gemini and Apollo flights.

- U.S. space exploration history on U.S. stamps#Space Achievement Decade Issue of 1971 (Apollo 15 mission commemorated)

Notes

- ↑ An office whose duties included aiding astronauts in the time leading up to their spaceflights

- ↑ Die proofs, perforated by hand were used rather than actual stamps.

- ↑ Scott catalogue numbers 1434–1435.

- ↑ Rathmann owned a Cocoa Beach car dealership, and was friendly with many astronauts, for whom he got discount prices on General Motors automobiles. See Chaikin, p. 249.

- ↑ Scott catalogue number C76.

- ↑ On May 23, 1972, NASA issued a press release announcing that Irwin planned to retire, and based on that, a new backup crew for Apollo 17 was being put in place, excluding Scott and Worden. See NASA press release 72–113, "Astronauts Mitchell and Irwin to Retire", May 23, 1972.

- ↑ Scott testified at the August 3, 1972, hearing that two covers had gone astray from the expected number, but stated that he had never counted them and thus there might only have been 398 to begin with. See August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 15–16.

References

Additional numbers following page numbers for some books are Kindle locations.

- ↑ Dugdale, Jeff (March 30, 2013). "Astrophilately". The Philatelic Database. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 5.

- 1 2 Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Scott & Leonov 2004, pp. 328–330, 5414–5418.

- ↑ O'Toole, Thomas (September 16, 1972). "15 Astronauts Got Paid for Autographs: 15 Astronauts Given $2,500 for Autographs". The Washington Post. pp. A1, A4.

- 1 2 "Apollo Flown Covers". Chris Spain. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ↑ Weinberger, Howard C. "The Flown Apollo 11 Covers". Chris Spain. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Apollo 15". NASA. July 9, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Moon mail". National Postal Museum. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ↑ Irwin, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Hauglard, Vern (July 12, 1972). "3 Astronauts Disciplined over Smuggled Moon-Mail". The Washington Post. p. 1.

- 1 2 Weinberger, Howard C. "The Flown Apollo 15 Sieger Covers". Chris Spain. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- 1 2 Scott & Leonov 2004, pp. 328–330, 5418–5421.

- 1 2 O'Toole, Thomas (September 16, 1972). "Ex-Astronauts Disregarded Warning Against 'Souvenirs'". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 3.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Scott & Leonov 2004, pp. 328–330, 5425.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 149–150, 2679–2674.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 49.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 82.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 56.

- 1 2 Weinberger, Howard C. "Apollo Insurance Covers". Chris Spain. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 149–150, 2684–2688.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Chaikin, p. 445.

- ↑ Irwin, p. 228.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 17.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 148, 2648–2670.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 133–134.

- 1 2 Ulman, p. 284.

- 1 2 Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 7.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 14.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 148, 2671–2679.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 149, 2671–2679.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 26.

- ↑ Fletcher August 2, 1972 letter, p. 1.

- 1 2 August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 59.

- ↑ Hines, William (July 13, 1972). "Congresswoman charges NASA stamp 'runaround'". Chicago Sun-Times. pp. 2, 3.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 50.

- 1 2 Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 1, 7–8.

- 1 2 Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 109.

- 1 2 "Apollo 15 Stamps" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. July 11, 1972.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 107–109.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 150–151, 2697–2715.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 35.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 76.

- 1 2 Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 Faries, Belmont (June 18, 1972). "A Lunar Bonanza". The Washington Sunday Star.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 21.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 150, 4053–4075.

- ↑ Irwin, p. 116.

- ↑ Worden 2011, 4111.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 147.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 4, 11.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 14.

- ↑ Fletcher August 2, 1972 letter, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 148, 4321–4340.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 Chronology of 144 Authorized Covers, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 245, 4338.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 20.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 53–54, 98–100.

- ↑ Irwin, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Fletcher July 27, 1972 letter, p. 12.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 245, 4345.

- ↑ Irwin, p. 230.

- ↑ Management chronology, p. 1.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, p. 63.

- ↑ Slayton 1994, pp. 278–279, 5171–5180.

- ↑ Chaikin, p. 497.

- ↑ August 3, 1972 hearing, pp. 9, 24–25, 93–74.

- ↑ Management chronology, p. 2.

- ↑ Marsh, Al (July 12, 1972). "Astronauts 'Canceled' for 'Stamp Deal'". Today. pp. 12, 13.

- ↑ Lewis, p. 274.

- ↑ Scott & Leonov 2004, p. 329, 5434.

- ↑ Scott & Leonov 2004, p. 331, 5454.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 246–249, 4429–4464.

- ↑ Irwin, p. 235.

- ↑ Schneck, Harold M. Jr. (July 22, 1972). "NASA Concerned Over Moon Statue". The New York Times. p. 31.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 252–253, 4456–4473.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 254–255, 4496–4531.

- ↑ Lyons, Richard D. (August 4, 1972). "Atronauts [sic] and Space Officials Heard at Inquiry on Exploitation of Souvenirs". The New York Times.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 250–251, 4387–4443.

- 1 2 Connelly, Richard (August 2, 2011). "Apollo 15, 40 Years On: Five Odd Facts (Including Faulty Peeing, a Very Irked NASA & the Coolest Lunar Experiment)". The Houston Press. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 243, 4303.

- ↑ Howell, Elizabeth (April 8, 2013). "Al Worden: Apollo 15 Astronaut". SPACE.com. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ↑ "David R. Scott". International Space Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (August 10, 1991). "James B. Irwin, 61, Ex-Astronaut; Founded Religious Organization". The New York Times.

- ↑ Chaikin, p. 551.

- ↑ 14 CFR Part 1214, Subpart 1214.6 - Mementos Aboard NASA Missions

- ↑ Worden 2011, p. 269, 4770–4775.

- ↑ Worden 2011, pp. 268–269, 4531.

- ↑ Ulman, p. 285.

- 1 2 O'Toole, Thomas (July 29, 1983). "Covers Returned to Moon Astronauts: Estimated to Be Worth $500,000". The Washington Post. p. A4. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "U.S. Returns Stamps to Former Astronauts". The New York Times. July 30, 1983. p. 11.

- ↑ "Flown. From The Dave & Tracy Scott Collection". Highlights from the upcoming Novaspace auction. January 26th, 2008. Arizona Challenger Space Center. Novaspace. Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Auction Results". Novaspace. Archived from the original on November 12, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

Lot Number 391. Surface flown Apollo 15 cover. $15000.00.

- ↑ "Item 477 – Apollo 15 Catalog 442 (Nov 2014)". RRAuction. RRAuction. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ Powell, Corey S.; Shapiro, Laurie Gwen (December 16, 2013). "The Sculpture on the Moon". Slate. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

Sources

- Chaikin, Andrew (1998) [1994]. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. New York, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-024146-4.

- Fletcher, James C. (July 27, 1972). "Letter from James C. Fletcher to Clinton P. Anderson". (exhibit to August 3, 1972, committee hearing). (Subscription required (help)).

- Fletcher, James C. (August 2, 1972). "Letter from James C. Fletcher to Clinton P. Anderson". (exhibit to August 3, 1972, committee hearing). (Subscription required (help)).

- Irwin, James B.; Emerson Jr., William A. (1982) [1973]. To Rule the Night: The Discovery Voyage of Astronaut Jim Irwin. Nashville, TN: Broadman Press. ISBN 978-0-8054-7227-1.

- Lewis, Richard S. (1974). The Voyages of Apollo: The Exploration of the Moon. New York, NY: Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co. ISBN 978-0-8129-0477-2.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (1972). "Chronology of 144 Authorized Covers". (exhibit to August 3, 1972, committee hearing). (Subscription required (help)).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (1972). "Chronology of 400 Unauthorized Covers". (exhibit to August 3, 1972, committee hearing). (Subscription required (help)).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (1972). "Management Chronology". (exhibit to August 3, 1972, committee hearing). (Subscription required (help)).

- Scott, David; Leonov, Alexei (2004). Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-7434-5067-6.

- Slayton, Deke; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke!. New York, NY: Forge. ISBN 978-0-312-85918-3.

- Ulman, Leon (1981), "78-64 Memorandum Opinion for the Assistant Attorney General, Civil Division", in Ulman, Leon, Opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel (January 11, 1978 – December 31, 1978), 2, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, pp. 281–289, ISBN 978-0-936502-00-7

- United States Senate Committee on Aeronautics and Space Sciences (August 3, 1972). "Commercialization of Items Carried by Astronauts". United States Senate. (Subscription required (help)).

- Worden, Al; French, Francis (2011). Falling to Earth: An Apollo 15 Astronaut's Journey to the Moon. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-58834-310-9.

External links

- NASA News Release 72-189, "Articles Carried on Manned Space Flights" from collectspace.com