Amphibalus

| Saint Amphibalus | |

|---|---|

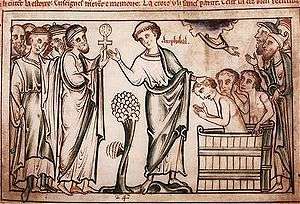

Saint Amphibalus baptizing converts | |

| Martyr | |

| Born |

unknown Isca (Caerleon) |

| Died |

25 June 304 Verulamium (St Albans), Hertfordshire |

| Venerated in |

Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | St Albans Cathedral, Hertfordshire (reconstructed medieval shrine) |

| Feast | 25 June (or 24 June) |

| Attributes | Priest with cloak |

| Patronage | The Christian persecuted |

| Controversy | 'Amphibalus' is almost certainly not his real name; many of the major details of his life may be medieval embellishments |

Saint Amphibalus is a venerated early Christian priest said to have converted Saint Alban to Christianity. He occupied a place in British hagiography almost as revered as Saint Alban himself.[1] According to many hagiographical accounts, including those of Gildas, Bede, Geoffrey of Monmouth, and Matthew of Paris, Amphibalus was a Roman Christian fleeing religious persecution under Emperor Diocletian. Saint Amphibalus was offered shelter by Saint Alban in the Roman city of Verulamium, in modern-day England. Saint Alban was so impressed with the priest's faith and teaching that he began to emulate him in worship, and eventually became a Christian himself. When Roman soldiers came to seize St. Amphibalus, Alban put on Amphibalus' robes and was punished in his place. According to Matthew Paris, after St. Alban's martyrdom, the Romans eventually caught and martyred Amphibalus as well.

Name and authenticity

Gildas (c. 570), Bede (c. 730) and the three texts of St Alban's Passio, going back as far as the 5th century, do not name Saint Amphibalus in their accounts of Saint Alban. They refer to Amphibalus not as a saint but simply as a priest and do not report his martyrdom.[2][3] Amphibalus gained his name and title[1] when Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) in the 12th century. It is possible that Geoffrey had been repeating a name for the priest that had come into common usage in his time,[4] but it is also possible that Geoffrey of Monmouth misunderstood the Latin word used for the cloak, amphiboles, which was worn by Saint Alban.

Wilhelm Levison [5] noted that the story of the name, which goes back to a 5th-century Passio Albani, is composed of borrowings from other lives of saints and it has, in his words, "no place in the ranks of Acta martyrum sincera; it is a legendary tale...."

Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey repeated the story of Alban's martyrdom as given by Bede in his famous Historia Regum Britanniae [6] (c. 1136), with the addition of the name of the confessor he shelters, Amphibalus.[7] He recounts a church of Amphibalus at Winchester where King Constantine consigned his son, Constans, to become a monk [8] and where another, later, Constantine killed one of the sons of Mordred.[9] Geoffrey may have gotten the name from Gildas, who describes his contemporary, Constantine, King of Dumnonia, as having dressed in the amphibalo, or 'cloak', of an abbot to murder two royal youths in a church.[10] This could also be the inspiration for Geoffrey's story about the murder of the son of Mordred, and his association of Amphibalus' church with kings called Constantine. How, or why the story about Alban became connected to the story of king Constantine remains somewhat mysterious, but might be an effect of Geoffrey's enterprising imagination, and confusion of sources.

New cult invented in 12th century

Other details about Amphibalus's cult originate with texts that appear to have been written with the purpose of creating a new cult, particularly to give a supportive context to the inventio, or 'discovery', of the body of Amphibalus at Redbourn, near St Albans in 1177. The texts were produced at St. Albans Abbey in the second half of the 12th century written by a monk, William of St Albans, during the abbacy of Simon (1167–1183). He provided an elaborate version of the story of Saint Alban and gave a prominent role in it to a new martyr-saint, Amphibalus, whose name he states to have found in Geoffrey's work.[11]

Fisher [12] wrote: "There can be no doubt entertained that the whole was a fraud.". Wilhelm Levison,[13] stated that: "The abbey had incurred heavy debts; anyone who knows the medieval misuse of pious belief and offering, will not be surprised to learn that just at this time the generosity of the devotees was stimulated by the discovery of the history and, what is more, of the relics of St Amphibalus." Benjamin Gordon-Taylor also suggests that "a principal motive for the initiation of the cult of St Amphibalus was the success of the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury” [14] (murdered in 1170).

The new story about Amphibalus that emerged (see below) is based on associations with Saint Alban. Wilhelm Levison noted,[15] that in the 6th-century account of Gildas were another two martyrs, Julius and Aaron, said to have been martyred together by the eighth century at Urbs Legionis, identified as Caerleon in Wales. Meanwhile, the large number of people supposedly martyred together with Amphibalus may have their origin in a mistranscription made in the course of the transmission of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum (St Jerome's Martyrology), which connected the large number of martyrs originally associated with Rufinus of Alexandria, with Saint Alban, under the date of the 22nd of June.

The location of the inventio at Redbourn was discovered near ancient Anglo-Saxon burial mounds. There were two knives said to have been found with Amphibalus, typical of an ancient pagan Anglo-Saxon burial.[16]

Benjamin Gordon-Taylor [17] notes that: "The cult of St. Amphibalus and his companions is unique in late twelfth-century England ... in that we are seeing a cult beginning almost from scratch." This phenomenon bears witness to the influence of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum at the time which lay behind the discovery of the grave of King Arthur at Glastonbury Abbey. This was around the same time that the bodies of Amphibalus and his companions were discovered, which Gordon-Taylor [18] suggests was also motivated in part by competition with the new Canterbury cult of St Thomas à Becket to gain pilgrims.

Hagiography

Most of what is known of Amphibalus's life is derived from hagiographic texts centered on Saint Alban, written hundreds of years after his death. He was believed to be a citizen of Caerleon during the 3rd or 4th century.[19] During a religious persecution, Alban sheltered Amphibalus from persecutors in his home. The priest was believed to be pious and faithful, and while in Alban's home he prayed and kept watch day and night. He instructed Alban with "wholesome admonitions," influencing Alban to abandon his previous religious beliefs and follow Amphibalus in the Christian faith. Alban was so inspired by his guest that he chose to sacrifice his own life in order to save Amphibalus.[20]

After the martyrdom of Alban, Amphibalus was believed to have returned to Caerleon, where he converted many others to Christianity, including the Saints Julius and Aaron. It is believed that he was eventually captured by the Romans and returned to Verulamium, where he was killed for his faith. Where and how he was killed is unclear. Some sources say he was beheaded others say he was stabbed. A later version of the legend says that Amphibalus and some companions were stoned to death a few days afterwards at Redbourn, four miles from St. Albans. Saint Amphibalus is known for being one of four martyrs of the early Christian church in Roman Britain along with Albus, Julius and Aron. There is little known about any of the four early Saints except that they seemed to all be acquainted with each other.[4]

In 1178, some 800 years after Amphibalus' traditional death date, his remains were discovered at Redbourn in Hertfordshire, England, near the town of St Albans. According to the tale, Saint Alban appeared in a vision to a monk named Robert, indicating that he wished to make the location of the remains of Amphibalus known. Robert followed the spirit of Saint Alban, and was led by the saint to the remains of Amphibalus and his companions. Healing miracles were performed immediately, and the abbot ordered the site to be excavated. Several bodies were discovered, and one body seemed consistent with the manner of Amphibalus' death. The body believed to belong to Saint Amphibalus was moved to Saint Alban's, where a shrine was constructed for the veneration of the relics.[21]

Veneration

The first shrine of St. Amphibalus stood before the Great Rood Screen in the Norman Abbey of St. Alban's, near the high altar on the north side of the shrine of St. Alban. In 1323, a portion of the abbey roof collapsed, damaging the shrine. The shrine was then moved to the north aisle of the chancel. Eventually, around 1350, the shrine was given a position in the center of the retrochoir, east of St. Alban's own shrine in the 'Saint's Chapel', complete with a stone tomb, paintings, and a silver gilt plate.[22]

The shrine was destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII and the pieces were used to block the eastern arches of "Saints Chapel." The relics were scattered; however, the remains of the shrine were discovered in the 19th century during renovations, and were reassembled in 1872 under the direction of Sir George Gilbert Scott. Today, the reassembled stone shrine can be seen in St. Alban's cathedral.

Traditionally, Amphibalus' feast day was held on 24 June.[23] Winchester Cathedral was under the patronage St. Amphibalus before it was dedicated to St Swithun.[24]

References

- 1 2 McCulloch, Florence (1981). "Saints Alban and Amphibalus in the Works of Matthew of Paris: Dublin, Trinity College MS 177". Speculum. 56 (4): 767. JSTOR 2847362.

- ↑ "Gildas On the Ruin of Britain" (PDF). Camelot On-line. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ "Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the People of England" (PDF). Camelot On-line. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- 1 2 Thurston, Herbert. "St. Alban." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 25 Dec. 2012

- ↑ Levison, Willhelm "St Alban and St Albans" in Antiquity 15, 1941, pp. 337-59, at p. 346.

- ↑ Wright, Neil, The Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth, 1984, Bern, Burgerbibliothek, MS. 568, Cambridge; trans Thorpe, Lewis Geoffrey of Monmouth: The History of the Kings of Britain, 1966, Penguin Classics; Online Latin text at Google Books; Online text at Google Books;

- ↑ Hist.Reg. V.5

- ↑ Hist.Reg. VI.5

- ↑ Hist.Reg. XI.4

- ↑ Gildas, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae 28; text & trans., Winterbottom, Michael, Gildas, the Ruin of Britain, 1978, London/Chichester: Phillimore; "Gildas' On the Ruin of Britain" (PDF). Camelot On-line. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Levison, op. cit; Gordon-Taylor, Benjamin Nicholas "The Hagiography of St Alban and St Amphibalus in the Twelfth Century," 1991, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6175/

- ↑ Gould, S. Baring and Fisher, J, 1907-13 Lives of the British Saints, 4 vols, London: Cymmrodorion Society; see https://archive.org/stream/livesofbritishsa01bariuoft#page/160/mode/2up

- ↑ Levison op.cit I, 354

- ↑ Gordon-Taylor op.cit Synopsis

- ↑ Levison op. cit p. 355

- ↑ Levison op.cit pp.35-6; Gordon-Taylor op.cit pp. 85-6

- ↑ Gordon-taylor op.cit p.110.

- ↑ Gordon-Taylor op.cit p.66

- ↑ Cambrensis, Giraldus. "The Intenerary Through Wales, and the Description of Wales". archive.org. Everyman Library. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Bede. "Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation". chapter VIII. Fordham University. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Page, William,ed., Houses of Benedictine monks: Redbourn Priory, A History of the County of Hertford: Volume 4 (1971), pp. 416-419

- ↑ Nash Ford, David. "Shrines of St. Albans: St. Amphibalus In and Out of Favor". The Holy Shrines of St. Albans in Hertfordshire. britannia.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Online, Catholic. "St. Amphibalus - Saints & Angels - Catholic Online". Catholic Online. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ The Buttercross, City of Winchester