Lavinia

In Roman mythology, Lavinia (/ləˈvɪniə/; Latin: Lāuīnĭa [laːˈwiːnia]) is the daughter of Latinus and Amata and the last wife of Aeneas.

Lavinia, the only child of the king and "ripe for marriage", had been courted by many men who hoped to become the king of Latium. Turnus, ruler of the Rutuli, was the most likely of the suitors, having the favor of Queen Amata. King Latinus is later warned by his father Faunus in a dream oracle that his daughter is not to marry a Latin.

"Propose no Latin alliance for your daughter,

Son of mine; distrust the bridal chamber

Now prepared. Men from abroad will come

And be your sons by marriage. Blood so mingled

Lifts our name starward. Children of that stock

Will see all earth turned Latin at their feet,

Governed by them, as far as on his roundsThe Sun looks down on Ocean, East or West."[1]

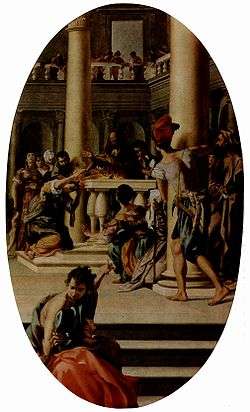

Lavinia has what is perhaps her most, or only, memorable moment in Book 7 of the Aeneid, lines 69–83: during sacrifice at the altars of the gods, Lavinia's hair catches fire, an omen promising glorious days to come for Lavinia and war for all Latins.

Aeneas and Lavinia had one son, Silvius. Aeneas named the city Lavinium for her. According to an account by Livy, Ascanius was the son of Aeneas and Lavinia; and she ruled the Latins as a power behind the throne, for Ascanius was too young to rule.

In other works

In Ursula K. Le Guin's 2008 novel Lavinia, the character of Lavinia and her relationship with Aeneas is expanded and elaborated, giving insight into the life of a king's daughter in ancient Italy. Le Guin employs a self-conscious narrative device in having Lavinia as the first-person narrator know that she would not have a life without Virgil, who, being the writer of the Aeneid several centuries after her time, is thus her creator.

Lavinia also appears with her father Latinus in Dante's Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto IV, lines 125–126.

Notes

- ↑ Aeneid 7.96–101, as translated by Robert Fitzgerald.

References

- Virgil. Aeneid. VII.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita Book 1.