Amazon Reef

Coordinates: 1°N 49°W / 1°N 49°W

The Amazon Reef forms an extensive system composed of corals, sponges and rhodoliths. Its features and the inhospitable region make this ecosystem unique.

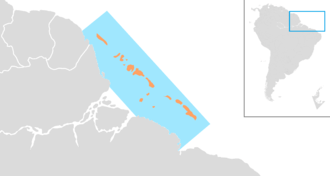

The reef lies at the mouth of the Amazon River basin, along the northern coast of Brazil, extending from Brazil’s border with French Guiana to the state of Maranhão.[2] It is one of the largest reef systems in the world, measuring approximately 1,000 km in length and covering an area of almost 9,500 km². Depths range between 30 and 120 meters.[3]

World Amazon Reef Day is celebrated on January 28. It was on this day, in 2017, that the first images of the reef system were released.[4]

Evidence of the reef’s existence has been known since the 1950s, but only in 2016[2] was it actually proven, a discovery held up by experts as one of the great finds in marine biology of the last few decades.[5]

The Amazon Reef ecosystem is already considered to be under threat from nearby oil exploration.[6] The companies BP and Total are trying to obtain environmental licenses from the Brazilian government to start drilling for oil at the mouth of the Amazon River basin in 2018.[7]

Location

The Amazon Reef lies at the mouth of the Amazon River basin, along Brazil’s northern coast. The reef covers an area of almost 9,500 km2, bordering three Brazilian states: Maranhão, Pará and Amapá and is located at least 120 km from the coast. And also lies along the coastline of French Guiana.[2] However, recent expeditions to the region of the reef indicate that the area could be up to five times larger.[3]

Discovery

Since the 1950s, the existence of the reefs hidden at the mouth of the Amazon River has been suspected. Fishing production in the state of Amapá, for example, is marked by large numbers of lobster and snapper, marine species naturally associated with reef ecosystems.

In 1975, an American research vessel studying shrimp stocks along the Brazilian coastline cast nets in areas nearby the Amazon River and found a diversity of species that, theoretically, should not be there. Fish and sponges common to reefs were found along the seafloor.[8]

The discovery was reported at a symposium in 1977, but no further progress was made thereafter. Only in 2010 did the region come under study again. A group of scientists, led by researchers from the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, travelled twice to the mouth of the Amazon River to confirm the findings of the article from decades before.

The expeditions were successful and they were able to obtain samples from the seafloor by dredging: many corals, sponges, fish and rhodoliths. The study that revealed the Amazon Reef was published in the journal Science Advances in April 2016. The work was signed by 39 authors from 12 institutions, of which 38 were Brazilian.[2]

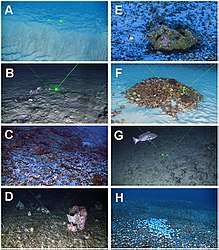

Despite the study and the evidence, before 2017 no one had gone to the sea floor to witness and record the inhabitants, colors and forms of this living system.

In January 2017, an expedition led by the NGO Greenpeace and some of the scientists responsible for the study published in Science Advances was assembled with the objective of obtaining the first underwater photographs and videos of the Amazon Reef.[9] The ship Esperanza, operated by Greenpeace, was equipped with underwater cameras and a manned submarine and spent 20 days recording on the ocean floor. Although no biological materials were collected, the team of researchers came away with new and important information that will help them better understand the ecosystem that forms the Amazon Reef.[10]

Since the expedition, scientists now estimate that the reef extends over an area five times larger than the 9,500 km2 calculated previously. And they saw fish species perhaps not yet catalogued by science.

Unique Features

The discovery of the Amazon Reef was surprising because there is no record of there ever being a reef at the mouth of a major river anywhere in the world. This system is considered a new biome, with unique features.[11]

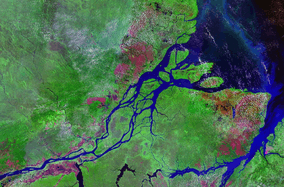

Reefs generally exist in shallow, crystalline saltwater that receives sunlight, since this light is used to produce food through photosynthesis. The conditions are quite different at the mouth of the Amazon River, where the water is muddy and turbid, with strong currents and freshwater mixed with seawater, altering the temperature and pH.

The waters of the region are turbid due to the influence of the Amazon River plume—a large amount of sediment from the Amazon rainforest, including the remains of trees, animals, minerals and debris that are carried by the current of the river. The plume is lighter than the seawater and remains suspended, blocking sunlight from reaching the bottom, where the reef is located.[12] Without sunlight, it is impossible for organisms to produce oxygen through photosynthesis.

This would also make the existence of this system impossible, but some adaptations have allowed the Amazon Reef to survive. Bacteria that use chemosynthesis are found instead of organisms that use photosynthesis as their primary source of energy. The sponges of these colonies feed off these bacteria, and this enables the existence of this ecosystem with these unprecedented features.[13]

Mehdi Adjeroud, research director at the Research Institute for Development, in France, a specialist in the ecology of Indo-Pacific coral reefs, said to the newspaper Le Monde', “In my classes at university, I teach students that coral reefs cannot develop near large rivers, like the Amazon or the Ganges".[14]

But the Amazon Reef proves that science understands little about this type of ecosystem. "This makes everything we published out of date. We are rewriting the textbooks,” said researcher Fabiano Thompson to the newspaper The Guardian.[15]

Despite the expeditions made to study the Amazon Reef, scientists believe that only 5% of its actual size is known. Nevertheless, catalogued species include:[2]

- 40 species of corals.

- 60 species of sponges, including 29 potentially unknown species.

- 73 species of typical reef fish, in addition to lobsters and starfish.

Pictures taken during the Greenpeace expedition revealed other organisms: groupers, wreckfish and snappers (species threatened with extinction), sardines, rays, starfish, spider crabs, lobsters, anemones, colonies of black corals and sponges and banks of rhodoliths. And possibly new species of butterflyfish.[10] Scientists also saw some species of fish they previously believed to only be present in Caribbean region. Now, they speculates a continuity of ecosystem from Abrolhos until the Caribbean waters.[16]

Threats from the oil industry

Despite their recent discovery, the Amazon Reef is already under threat from the petroleum industry. In 2013, the French company Total and the British firm BP participated in auctions by the Brazilian National Agency of Oil, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) and acquired oil exploration concessions for blocks at the mouth of the Amazon River, in areas near the Amazon Reef.[17] ANP estimates point to stocks of 14 billion barrels of oil located there.

BP owns and operates one block in the region and Total has five. The block nearest the reef system is owned by Total and is located only 8 km away. The first well that can be drilled is 28 kilometers from the Reef.

An oil spill in the region would threaten not only the reef, an extremely fragile biome, but also all forms of life at the mouth of the Amazon River, inhabited by numerous species at risk of extinction, such as the manatee and giant otter, according to data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Both BP and Total are trying to obtain environmental licenses from the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) to begin the first stage of exploration: the drilling of wells to determine the economic viability of oil extraction at that location for commercial purposes. Both have already submitted Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), but Ibama rejected the studies because the documents contained flawed and insufficient data.[18]

Campaign to protect the Amazon Reef

The possibility of oil exploration in the region of the Amazon Reef concerns environmentalists, scientists and even some celebrities. Since the first underwater images of the Reef were taken, the NGO Greenpeace began a worldwide campaign to force BP and Total to back away from oil exploration projects and Ibama to deny operating licenses.

Since January 2017, a variety of initiatives have been staged to pressure the companies and Ibama. And the website for the petition now has over 1.6 million signatures from people who support the campaign by Greenpeace.

In July 2017, celebrities and experts associated with marine biology published a letter expressing concern about the risks that oil exploration would pose to the region.[19] The document is signed by people like the Indian economist Pavan Sukhdev, the American oceanographer Sylvia Earle and British professors Jason Hall-Spencer and Murray Roberts. Among the Brazilian names are climatologist Carlos Nobre, physicist and IPCC member Paulo Artaxo, and some of the researchers responsible for the discovery of the Amazon Reef, such as Eduardo Siegle, Nils Edwin Asp Neto and Ronaldo Francini Filho.

The surfer Maya Gabeira endorsed the campaign to protect the Reef, as well as the band Midnight Oil, which, during a tour of Brazil in May 2017,[20] visited the ship Rainbow Warrior and threw their support behind the cause.[21]

According to environmentalists, the Amazon Reef must be protected from oil spills because of its importance, unique features and because so little is known about it.

The Environmental Impact Assessment submitted by BP and Total were also criticized by environmentalists. According to a critical analysis conducted by specialists in geology, hydrology, marine biology and the socioeconomic aspects of oil exploration, which was compiled and published by Greenpeace, the studies are flawed and present inconsistencies that compromise the accuracy of the assessment of impacts and the consequences of the activities proposed”.[22]

According to the critical analyses, the companies do not consider, for example, the influence of the Amazon River plume in the area where an oil spill could occur. This makes it impossible to predict the real impact if the oil spreads over the sea.

Total itself has already admitted that if a leak were to occur, the chances of oil reaching the Amazon Reef is roughly 30%.[23] High concentrations of oil can kill the Amazon Reef, which forms a unique biome about which we still know very little.

Protests from around the world

Since the Amazon Reef has entered the spotlight, the oil companies have faced various protests against the activities planned for Brazil.

The first protests by Greenpeace against plans by Total in Brazil, ended in the detention for several hours of activists who belong to the organization, including the executive director of the NGO, Bunny McDiarmid, who participated in the event. Forty activists from seven countries scaled a smoke stack of the company’s largest oil refinery in Europe, at the port of Antwerp, in Belgium, and unfurled a banner with a message: “Total, don’t destroy the reef”.[24]

In March, the American artist and activist John Quigley assembled a human banner with more than 600 people on Copacabana Beach.[25] Most were public school students from Rio de Janeiro. From above it read in Portuguese "Defend the Amazon Reef" and, later, the phrase changed to "No oil".

On same weekend in May, 450 Greenpeace activists from six countries took to the streets to protest against the French oil company Total and denounced the risks of oil expiration near the Amazon Reef.[26]

The company was also the target of protests by 30 activists who, in front of its headquarters, in Rio de Janeiro, simulated an oil spill and carried banners with phrases like "Total, back off the Amazon Reef" and "The people say no. Science says no. Ibama says no".[27]

At the BP’s headquarters in London, dozens of people marched with giant marine animals to show the company the life that is at risk in case of an accident.[28] Again in Great Britain, the character SpongeBob SquarePants was used as a symbol[29] for the Greenpeace campaign to protect the reef, rhodoliths and sea sponges, like him.

References

- ↑ Francini-Filho, Ronaldo B.; Asp, Nils E.; Siegle, Eduardo; Hocevar, John; Lowyck, Kenneth; D'Avila, Nilo; Vasconcelos, Agnaldo A.; Baitelo, Ricardo; Rezende, Carlos E. (2018). "Perspectives on the Great Amazon Reef: Extension, Biodiversity, and Threats". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00142. ISSN 2296-7745.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moura, Rodrigo L.; Gilberto M. Amado-Filho, Fernando C. Moraes, Poliana S. Brasileiro, Paulo S. Salomon, Michel M. Mahiques, Alex C. Bastos, Marcelo G. Almeida, Jomar M. Silva Jr, Beatriz F. Araujo, Frederico P. Brito, Thiago P. Rangel, Braulio C. V. Oliveira, Ricardo G. Bahia, Rodolfo P. Paranhos, Rodolfo J. S. Dias, Eduardo Siegle, Alberto G. Figueiredo Jr, Renato C. Pereira, Camille V. Leal, Eduardo Hajdu, Nils E. Asp, Gustavo B. Gregoracci, Sigrid Neumann-Leitão, Patricia L. Yager, Ronaldo B. Francini-Filho, Adriana Fróes, Mariana Campeão, Bruno S. Silva, Ana P. B. Moreira, Louisi Oliveira, Ana C. Soares, Lais Araujo, Nara L. Oliveira, João B. Teixeira, Rogerio A. B. Valle, Cristiane C. Thompson, Carlos E. Rezende, Fabiano L. Thompson (April 1, 2016). «An extensive reef system at the Amazon River mouth». Science Advances (in English). 2 (4): e1501252. ISSN 2375-2548. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501252

- 1 2 <<Pesquisa com apoio da CAPES descobre maior bioma marinho do Brasil>> Fundação Capes. March 22, 2017.

- ↑ <<Amazon Reef: First images of new coral system>> BBC News. January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Surprising, Vibrant Reef Discovered in the Muddy Amazon>>. National Geographic. April 22, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Huge coral reef discovered at Amazon river mouth>>. The Guardian. April 22, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<The Amazon town, a coral reef, big oil, and a catastrophe waiting to happen>>. The Guardian. December 27, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<O recife que ninguém viu>>. Piauí. December 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Recife na foz do Amazonas é único no mundo>> Folha de S. Paulo. January 23, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- 1 2 <<Os Corais da Amazônia surpreenderam nossa expectativa e imaginação>>. Greenpeace Brasil. February 16, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<First images of unique Brazilian coral reef at mouth of Amazon>>. The Guardian. January 31, 2017.

- ↑ <<Um recife vitaminado pela floresta>>. Greenpeace Brasil. February 22, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Como cientistas descobriram um recife "impossível" na foz do Amazonas>>. Época magazine. May 3, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Un improbable récif corallien au large de l’Amazone>>. March 20, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<'We are rewriting the textbooks': first dives to Amazon coral reef stun scientists>> The Guardian. February 17, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Entre os corais e o petróleo>>. Uol. February 16, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Foz do Amazonas Basin” 11th Licensing Round presentation. ANP>> Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Ibama rejeita estudo para exploração de petróleo na Foz do Amazonas>>. August 29, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Scientists and public figures call for Amazon Reef protection – the full letter>> July 31, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Postcard from Brazil>>. Midnight Oil. May 5, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<MIDNIGHT OIL joins the struggle to defend the Amazon Reef>> Scoop Independent News. July 28, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Amazônia em águas profundas>>. September 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Oil giants admit potential spill could have 30% chance of hitting Amazon reef>>. Unearthed. 4 de julho de 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Greenpeace protest coral reef destruction by Total>>. Flanders News. 27 de março de 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Greenpeace faz ato na Praia de Copacabana em defesa de corais da Amazônia>> EBC News. March 29, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<O mundo todo contra a exploração de petróleo perto dos Corais da Amazônia>> Greenpeace. May 30, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Greenpeace Protests against Plans for Oil Drilling near Amazon Mouth>> Latin American Tribune. September 29, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ <<Greenpeace activists march through London carrying inflatable sea creatures to protest against BP oil drill>> Evening Standard. August 21, 2017.

- ↑ <<Spongebob fronts Greenpeace attack ad targeting BP & Total over Amazon oil drilling>> July 5, 2017.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amazon Reef. |