Al-Waleed bin Talal

| His Royal Highness Prince Al-Waleed Bin Talal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Alwaleed bin Talal |

| Born |

7 March 1957 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia |

| Residence | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

| Nationality | Saudi |

| Alma mater |

Menlo College Syracuse University |

| Occupation | Chairman & CEO of Kingdom Holding Company |

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Net worth | US$ 18.7 billion |

| Spouse(s) |

Dalal bint Saud bin Abdulaziz (divorced) Eman bint Naser bin Abdullah al Sudairi (divorced) Ameera al-Taweel (divorced) |

Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal bin Abdulaziz al Saud (Arabic: الوليد بن طلال بن عبدالعزيز آل سعود, born 7 March 1957)[1] is a Saudi businessman, investor, philanthropist, and a member of the Saudi royal family. He was listed on Time magazine's Time 100, an annual list of the hundred most influential people in the world, in 2008.[2] Al-Waleed is a grandson of Ibn Saud, the first Saudi king, a half-nephew of all Saudi kings since, and a grandson of Riad Al Solh (Lebanon's first prime minister).

He is the founder, chief executive officer and 95-percent owner[3] of the Kingdom Holding Company, a Forbes Global 2000 company with investments in companies in the financial services, tourism and hospitality, mass media, entertainment, retail, agriculture, petrochemicals, aviation, technology and real-estate sectors.[4] In 2013, the company had a market capitalization of over $18 billion.[5] Al-Waleed is Citigroup's largest individual shareholder, the second-largest voting shareholder in 21st Century Fox, a minor shareholder in Zaveriwala Holdings LLC and owns Paris' Four Seasons Hotel George V and part of the Plaza Hotel.[6][7] Time has called him the "Arabian Warren Buffett".[8][9][10] In November 2017 Forbes listed Al-Waleed as the 45th richest man in the world, with an estimated net worth of $18.7 billion.[11][12]

The previous year, he announced that he would donate his fortune to charity at an unspecified date. Some of the reasons he cited were to foster cultural understanding and empower women.[13]

On 4 November 2017 he and other prominent Saudis (including fellow billionaires Waleed bin Ibrahim Al Ibrahim and Saleh Abdullah Kamel) were arrested in Saudi Arabia, in a purge that the Saudi government characterized as an anti-corruption drive.[14][15] The allegations against Prince Al-Waleed include money laundering, bribery, and extorting officials.[16] Some of the detainees have been in the Ritz Carlton Riad since then.[17] Al-Waleed was released from detention on 27 January 2018, following a financial settlement of some kind, after nearly three months in detention.[18][19] In March 2018 he dropped out from the World's Billionaires's list.[20]

Early life and education

Al-Waleed was born in Jeddah on 7 March 1955[21][22] to Prince Talal bin Abdul-Aziz, long-time known as The Red Prince, and Mona Al Solh, daughter of Riad Al Solh (Lebanon's first prime minister).[23][24] His father was Saudi Arabia’s finance minister during the early 1960s,[25] before he went into exile due to his advocacy for political reform.[26] Al-Waleed's grandmother was Munaiyir, whose family escaped the Armenian Genocide. She was presented by the emir of Unayza to Ibn Saud in 1921, when she was 12 years old and Ibn Saud was 45.[27]

Al-Waleed's parents separated when he was seven, and he lived with his mother in Lebanon.[26] As a boy, he ran away from home for a day or two at a time (sleeping in unlocked cars) before attending military school in Riyadh.[26] Al-Waleed received a bachelor's degree in business administration from Menlo College in California in 1979,[28] and a master's degree with honors in social science from Syracuse University in 1985.[29]

Business career

Al-Waleed began his business career in 1979 after graduating from Menlo College. He returned to Saudi Arabia, which was in the midst of the 1974–85 oil boom.[30] Operating from a small, pre-fabricated office in Riyadh, al-Waleed was successful in construction contracts and real estate. He was first profiled by Forbes in 1988.

After the end of the Saudi oil boom, al-Waleed acquired the underperforming United Saudi Commercial Bank. Through mergers with Saudi Cairo Bank and the Saudi American Bank, it became a leading Middle Eastern bank.[31]

He bought a substantial tranche of shares in Citicorp in 1991, when the company was in crisis. From an initial investment of $550 million ($2.98 per share after adjustments for stock splits, acquisitions and spin-offs, according to Bloomberg calculations) to bail out Citibank's underperforming American real-estate and Latin American business-loan portfolios, his holdings in Citigroup grew to about $1 billion.

Time reported in 1997 that al-Waleed owned about five percent of News Corporation.[32] In 2010 his News Corporation stake was about seven percent ($3 billion). Three years later News Corporation had a $175 million (19-percent) investment in al-Waleed's Rotana Group, the Arab world's largest entertainment company. A review of his holdings implied that al-Waleed had sold his investment in AOL.[33]

His stake in Citibank accounted for approximately half his wealth before the financial crisis of 2007–08. At the end of 1990 al-Waleed bought 4.9 percent of Citicorp’s common stock for $207 million ($12.46 per share), the maximum before he would be legally obliged to declare his investment. In February 1991 he spent $590 million on new preferred shares, convertible to common shares at $16 each. This, an additional 10 percent of Citicorp, brought al-Waleed's stake to 14.9 percent.[34]

In 1999 The Economist expressed doubts about the source of his income, wondering if he was a front man for other Saudi investors:

He has not earned enough income from his investments to pay for all that he has spent in the 1990s. The mystery goes back to that first stake in Citicorp. The prince has declared that this money came entirely from his personal funds. He says he started out in 1979 with a loan of just $30,000 from his father. He also mortgaged a house that his father had given him, raising something like $400,000. And each month, as a grandson of Ibn Saud, he receives $15,000. You could barely clothe a Saudi prince for such sums, let alone furnish him with a multi-billion-dollar empire. Nevertheless, by 1991 Prince Alwaleed had felt able to risk an investment of $797m in Citicorp.[34]

Al-Waleed invested in AOL, Apple, MCI, Motorola, Fox Broadcasting and other technology and media companies.[35] His stake in Apple was sold in 2005.[26] Al-Waleed also invested in Eastman Kodak and TWA, both of which performed moderately well.[36]

His real-estate holdings included large stakes in the Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts and New York's Plaza Hotel; al-Waleed sold half his shares in the Plaza in August 2004. He has invested in London's Savoy Hotel and Monaco's Monte Carlo Grand Hotel. Al-Waleed holds a ten-percent stake in Euro Disney SCA, the company which owns, manages and maintains Disneyland Paris in Marne-la-Vallée.[37]

In January 2005 Al-Waleed purchased the Savoy Hotel in London for an estimated £250 million, to be managed by Fairmont Hotels and Resorts; his sister, Sultana Nurul, owns an estimated 16-percent stake. In January 2006, in partnership with the U.S. real-estate firm Colony NorthStar, Kingdom Holding acquired Toronto-based Fairmont Hotels and Resorts for an estimated $3.9 billion. It was reported in 2009 that Al-Waleed owned 35 percent of Research and Marketing Group (SRMG), a large Mideast media company.[38]

In August 2011 al-Waleed announced that his company had contracted with the Saudi Binladin Group to build the world's tallest building, the Kingdom Tower (at a height of at least 1,000 metres (3,300 ft)) for SR 4.6 billion.[39] The original plan—announced in 2008—called it برج الميل (Arabic for "One-Mile Tower"), at a height of 1,609 metres (5,279 ft)[40] and an estimated cost of $20 billion.[41]

In December 2011 Al-Waleed invested $300 million in Twitter, purchasing secondary shares from insiders.[42] The purchase gave Kingdom Holding a "more than 3% share" in the company, which was valued at $8 billion in late summer 2011.[3]

Arrest and release

On 4 November 2017, Al-Waleed was arrested in Saudi Arabia in a "corruption crackdown" conducted by a new royal anti-corruption committee.[48] This was done on authority of Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, his cousin (both are grandsons of Ibn Saud, first monarch and founder of Saudi Arabia).

Just days before his arrest, Al-Waleed reportedly contacted US-based Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi (who has publicly criticized the Saudi government in the past) and invited him to return to the Kingdom in order to contribute to Mohammad bin Salman's vision.[49]

Al-Waleed was released from detention in late January 2018, nearly three months after his arrest,[19] after he and most of the other Saudi notables arrested the previous year had made a financial settlement of some kind with the Saudi government.[18]

Forbes dispute

In 2013 Kerry Dolan, editor of Forbes' annual billionaires' list, wrote an article accompanying the list entitled "Prince Alwaleed and the Curious Case of Kingdom Holding Stock".[26] According to Dolan, al-Waleed attached great importance to the Forbes list and she alleged a correlation between changes in the share price of Kingdom Holdings and the annual run-up to the list's publication.[26] Jeffrey Towson, al-Waleed's former head of direct investments for MENA and Asia-Pacific, published a report on his blog in response to the Forbes article entitled "The 8 Big Mistakes in Forbes' Attack on Prince Alwaleed".[50] Towson wrote, "Forbes' explanation of his [al-Waleed's] behavior, his business and his investment strategy is one of the worst I have ever seen. The tone is bad. But the content is worse."[50] According to Towson, the magazine skewed the axis of its published-share-price chart to support the correlation.[50] In the Forbes article, Dolan wrote that al-Waleed would blind copy Dolan on text messages he sent to prominent people in an attempt to impress her. She spent a week with him in Riyadh in 2008, at his behest, touring his palaces. In 2006 Forbes estimated al-Waleed's net worth at $7 billion less than he claimed. He telephoned Dolan at home, according to the editor, "nearly in tears".[26] Al-Waleed had Kingdom Holding's chief financial officer fly to New York before a previous list was published to ensure that Forbes used his stated numbers.[26]

The article explains the methodology behind Forbes' 2013 estimate of his wealth at $20 billion, examines Kingdom Holdings' share performance and contains Dolan's communications with Kingdom Holdings CFO Shadi Sanbar. Sanbar demanded that al-Waleed’s name be removed from the billionaires' list if Forbes did not increase its valuation of his wealth.[26] Dolan wrote, "As Forbes asked increasingly specific questions in the process of fact-checking this story, the prince acted unilaterally the day before it was published, announcing through his office that he would 'sever ties' with the list."[26] Sanbar said in a press release, "Prince Alwaleed has taken this step as he felt he could no longer participate in a process which resulted in the use of incorrect data and seemed designed to disadvantage Middle Eastern investors and institutions."[26]

Al-Waleed said in a March 2013 interview with The Sunday Telegraph that he would pursue legal action against Forbes.[51] "They are accusing me of market manipulation," Al-Waleed said. "This is all wrong and a false statement. We will fight it all the way against Forbes."[51] He called the Forbes list "flawed and inaccurate", saying that it "displays bias against Middle East investors and financial institutions."[51]

The Guardian reported that on 6 June 2013, al-Waleed had brought a defamation claim in London against the publisher of Forbes; its editor, Randall Lane, and two journalists from the magazine.[52] Forbes expressed surprise at the libel action and the fact that it was filed in London.[52] According to the magazine, "The Prince's suit would be precisely the kind of libel tourism that the UK's recently-passed libel reform law is intended to thwart. We would anticipate that the London high court will agree. Forbes stands by its story."[52] As of 20 June, Forbes had not been served with papers.[53]

A statement issued by the Kingdom Holding Company accused Forbes of publishing a "deliberately insulting and inaccurate description of the business community in Saudi Arabia and specifically, Forbes' denigration of the Saudi stock exchange (Tadawul), which is one of the most regulated in the world". According to al-Waleed, the magazine used an "irrational and deeply flawed valuation methodology, which is ultimately subjective and discriminatory".[54]

On 16 June 2015, Forbes and al-Waleed released a joint statement announcing that they had settled their dispute "on mutually agreeable terms". The opening of the Saudi stock exchange to foreign investors was cited as key in the defendants' willingness to consider the stock price of al-Waleed's publicly traded Kingdom Holding Company in valuing the KHC component of his wealth.[55]

Political views

Al-Waleed urged Arab nations to give up their hostility toward Israel and seek peaceful coexistence.[56] He later tweeted that the statement was a fabrication.[57][58] Al-Waleed tweeted a statement with a picture of himself holding an honorary Palestinian passport, "In response to the news of the visit to Israel: I have not and will not visit Jerusalem or pray inside it until its liberation from the Zionist enemy. And I carry an honorary Palestinian passport".[59] A Syrian article questioned his statement.[60]

In 2015, al-Waleed was criticised for offering to buy Bentley cars for Saudi fighter pilots involved in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen. In a tweet later deleted, he said: "In appreciation of their role in this operation, I'm honoured to offer 100 Bentley cars to the 100 Saudi [fighter] pilots".[61]

Philanthropy

Al-Waleed is also a philanthropist, and much of his charitable activity is in the field of educational initiatives to bridge gaps between Western and Islamic communities. He has funded centers of American studies in universities in the Middle East and centers of Islamic studies in Western universities, which, in 2005, led Campus Watch and the American Jewish Congress to question the centers' academic autonomy.[62] In 2002, al-Waleed donated $500,000 to help fund the George Herbert Walker Bush scholarship at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.[33] and donated £18.5 million to Palestinian families during a TV telethon ordered by Saudi King Fahd to help relatives of Palestinians after Israeli operations in the West Bank city of Jenin. In 2004, he contributed $17 million to victims of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami.[63]

On July 1, 2015, al-Waleed held a press conference announcing his intention to donate $32 billion to philanthropic causes. He said that the funds would be used for humanitarian projects such as the empowerment of women and youth, disaster relief, disease eradication and building bridges of understanding between cultures.[64]

Donation after 11 September attacks

After the September 11 attacks, al-Waleed gave a check for $10 million to New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, despite Saudi opposition. In a written statement after his donation, he said: "At times like this, we must address some of the issues that led to such a criminal attack. I believe the government of the United States of America should re-examine its policies in the Middle East and adopt a more balanced stance toward the Palestinian cause." As a result of that statement, Giuliani returned his check.[65][66] Al-Waleed said to a Saudi weekly magazine about Giuliani's rejection of his check, "The whole issue is that I spoke about their position [on the Middle East conflict] and they didn’t like it because there are Jewish pressures and they are afraid of them."[67]

Western universities

In 2005, al-Waleed gave Georgetown University $20 million to create the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding (ACMCU) in the university's School of Foreign Service, the second largest donation in the school's history.[68] On 8 May 2008, al-Waleed gave £16 million to Edinburgh University to fund a "centre for the study of Islam in the contemporary world".[69] He has also endowed the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud Center for American Studies and Research (CASAR).[70] The Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Weill Cornell Medical College is named for al-Waleed.[71] The Centre of Islamic Studies at the University of Cambridge[72] and the Islamic Studies Program at Harvard University are also named after him.[73][74]

First Saudi female pilot

Al-Waleed is considered a proponent of female emancipation in the Saudi world. He financed the training of Hanadi Zakaria al-Hindi as the first Saudi woman commercial airline pilot, and said at her graduation that he is "in full support of Saudi ladies working in all fields".[75] Al-Hindi became certified to fly within Saudi Arabia in 2014.[76]

Assets

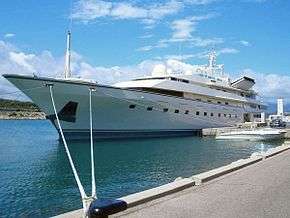

Al-Waleed owns the 65th-largest private yacht in the world, the 85.9-meter (282-ft) Kingdom 5KR (originally built as the Nabila for Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi in 1979). In 1983, owned by Khashoggi, it appeared as the Flying Saucer (the yacht of James Bond's villain, Largo) in Never Say Never Again. It was sold to Donald Trump, who renamed her the Trump Princess. Al-Waleed bought the yacht after Trump experienced financial problems in the late 1980s.[77]

Al-Waleed ordered a yacht known as the New Kingdom 5KR, about 173 meters (567 ft) long with an estimated cost of over $500 million. The yacht is designed by Lindsey Design, and its design was delivered in late 2010.[78] However, there has been no recent news regarding the yacht.

He owns several aircraft converted for private use: a Boeing 747,[79] an Airbus 321 and a Hawker Siddeley 125. Al-Waleed was the first individual to purchase an Airbus A380 and was due to take delivery of it in the spring of 2013, but it was sold before delivery.[36]

Among his assets are a 95-percent stake in Kingdom Holding Company; 91-percent ownership of Rotana Video and Audio Visual Company; 90-percent ownership of the Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation; seven-percent ownership of News Corporation; about six-percent ownership of Citigroup, and a 17-percent ownership of Al Nahar and a 25-percent ownership of Ad-Diyar (two daily newspapers published in Lebanon). Al-Waleed topped the first Saudi Rich List in 2009, with assets of $16.3 billion.[80]

Palaces

Al-Waleed owns three palaces: two existing and a third under construction. The 250,000-square-foot (23,000 m2) Kingdom Palace, in central Riyadh, is his primary home. According to Time magazine, "Al-Waleed lives in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in a $130 million sand-colored palace whose 317 rooms are adorned with 1,500 tons of Italian marble, silk oriental carpets, gold-plated faucets and 250 TVs. It has four kitchens, for Arabic, Continental and Asian cuisines, and a fifth just for dishing up desserts, run by chefs who can feed 2,000 people on an hour's notice. There is also a lagoon-shaped pool and a 45-seat basement cinema".[81] The 500,000-square-foot (46,000 m2) Kingdom Resort, also in central Riyadh, has three lakes interspersed with gardens. The 4,000,000-square-foot (370,000 m2) Kingdom Oasis, under construction, will have a 70,000-square-metre (17-acre) lake and a private zoo.

Awards

Al-Waleed received the first order[82] of the Order of King Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia[83] in 2002 and is a recipient of the Lebanese National Order of the Cedar.[83] On 2 December 2009, he received the Order of Izzudin from Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed;[84] that year he also received the Star of Palestine, the highest honour conferred by the State of Palestine.[85] In 2010, al-Waleed received the Dwight D. Eisenhower Award for Innovation.[86] He received the Bahrain Medal of the First Order, the country’s highest honorary medal in late May 2012.[87] He received the Nepalese third-order Mahaujjval Rastradip Manpadvi, the highest award bestowed on a foreigner,[88] and Guinea-Bissau's Colina De Boe Medal in August 2012.[89] In June 2013 al-Waleed was made Grand Commander of the Order of the Republic of Sierra Leone (GCRSL), the country's highest honour.[90] On 13 December 2014, he was made an Honorary Companion of the National Order of Merit of the Republic of Malta.[91]

Honours

- Order of Abdulaziz al Saud.

- 2016: Grand Officer in the Order of Grimaldi.[92]

Personal life

Al-Waleed has been married four times.[93] His first wife was his cousin, Dalal bint Saud, a daughter of King Saud. They have two children (Prince Khaled,[94] born 1978 and Princess Reem, born 1982),[95] and later divorced.[96] After divorcing his second wife, Al-Waleed married Kholood Al Anazi.[97][98] His fourth wife was Ameera al-Taweel; after about six years of marriage, they divorced in 2014.[93] In an interview, he said: "Yes, I announce it through Okaz - Saudi Gazette for the first time. I have officially separated from Princess Ameera Al-Taweel, but she remains a person that I have all respect for."[99]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Al-Waleed bin Talal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia's Prince Alwaleed's Timeline". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Khan, Riz (12 May 2008). "Prince Alwaleed bin Talal". Time. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- 1 2 Knickmeyer, Ellen, "Saudi prince invests $300M for 3% stake in Twitter" Archived 7 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Zawya Dow Jones via affiliate Market Watch, 19 December 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011

- ↑ "Alwaleed About". Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Kingdom Holding on the Forbes Global 2000 List". Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "The 2009 TIME 100 Finalists". 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016 – via content.time.com.

- ↑ Cohan, William D. "The Creation Myth of Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, Saudi Arabia's Billionaire Investor". Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud". Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "The mystery of the world's second-richest businessman". The Economist. 25 February 1999. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Jehl, Douglas (28 March 1999). "Buffett of Arabia? Well, Maybe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "Saudi Billionaire Alwaleed bin Talal's Net Worth Takes A Hit After News Of His Arrest". Forbes. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Maceda, Cleofe. "Senior Web Reporter". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 Kirkpatrick, David D. (4 November 2017). "Saudi Arabia Arrests 11 Princes, Including Billionaire Alwaleed bin Talal". New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ "Alwaleed bin Talal, two other billionaires tycoons among Saudi arrests". Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ↑ "Future Saudi king tightens grip on power with arrests including Prince Alwaleed". Reuters. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, billionaire investor, is released from custody in Saudi Arabia, relative says Archived 27 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. (27 January 2018)

- 1 2 "Saudi billionaire Prince Al-Waleed freed after 'settlement'". Agence France-Presse. 27 January 2018. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

The prince was released following an undisclosed financial agreement with the government, similar to deals that authorities struck with most other detainees in exchange for their freedom.

- 1 2 Ben Hubbard, Billionaire Saudi Prince, Alwaleed bin Talal, Is Freed From Detention Archived 27 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine., New York Times (January 27, 2017).

- ↑ Dolan, Kerry (6 March 2018). "Why No Saudi Arabians Made The Forbes Billionaires List This Year". Forbes. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Gornail, Jonathan (8 March 2013). "Newsmaker: Prince Al Waleed bin Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud". The National. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ Zuhur, Sherifa (31 October 2011). Saudi Arabia. ABC-CLIO. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-59884-571-6. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ Fandy, Mamoun (2007). (Un)civil War of Words: Media and Politics in the Arab World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-275-99393-1. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ Moubayed, Sami (1 February 2011). "Lebanon cabinet: A tightrope act". Lebanon Wire. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Yitzhak Oron, Ed. (1961). "The Saudi Arabian Kingdom". Middle East Record. 2: 417–431 (419).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Dolan, Kerry A. (5 March 2013). "Prince Alwaleed And The Curious Case Of Kingdom Holding Stock". Forbes. New York. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ "Asia Times Online".

- ↑ Peel, Michael (8 March 2013). "Prince Alwaleed, singular Saudi scion". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ "Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Al Saud". Forbes. March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ Saudi Arabia. Economic Policy During the Oil Boom, 1974–85 Archived 29 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. country-data.com

- ↑ "Prince Waleed: The Saudi dealmaker on Wall Street". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ↑ Macleod, Scott (1 December 1997). "Prince Alwaleed: The Prince and the Portfolio". Time. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- 1 2 Gustin, Sam (16 August 2010) "News Corp., the Saudi Prince and the 'Ground Zero Mosque'" Archived 21 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine., Daily Finance (AOL), via Rich, Frank (21 August 2010) "How Fox Betrayed Petraeus" Archived 23 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine.,The New York Times, p. WK8 NY ed.. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- 1 2 "'The mystery of the world's second-richest businessman'". The Economist. 25 February 1999. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ↑ "Kingdom Holding Company (KHC)". Zawya. 30 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- 1 2 Neville, Simon; Moulds, Josephine (5 March 2013). "Prince Alwaleed bin Talal insulted at only being No 26 on Forbes rich list". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ Disneyland Resort Paris, Annual review 2007, p. 53

- ↑ "Ideological and Ownership Trends in the Saudi Media". Cablegate. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Khan, Ghazanfar Ali; Abbas, Maher (2 August 2011). "Kingdom Holding to build world's tallest tower in Jeddah". Arab News. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Shaw, Matt. "10 Facts About the Kingdom Tower, the Soon-To-Be Tallest Building in the World" Archived 17 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Architizer, 22 April 2014. Accessed 15 March 2016.

- ↑ Pink, Roger. "Scraping the Sky: The 1 km-Tall Kingdom Tower" Archived 27 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Globalspec, 19 February 2015. Accessed 15 March 2016.

- ↑ Primack, Dan (19 December 2011). "Twitter doesn't really raise money from Saudi prince". Fortune. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia princes detained, ministers dismissed". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ Kalin, Stephen; Paul, Katie (5 November 2017). "Future Saudi king tightens grip on power with arrests including Prince Alwaleed". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ↑ "Corruption crackdown in Saudi Arabia". Fox Business. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ David, Javier E. (5 November 2017). "Billionaire Saudi Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal arrested in corruption crackdown". cnbc. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Stancati, Margherita; Said, Summer; Farrell, Maureen (5 November 2017). "Saudi Princes, Former Ministers Arrested in Apparent Power Consolidation". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ [43][44][45][46][47][14]

- ↑ "Saudi anti-corruption purge: All the latest updates". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Towson, Jeffrey. "The 8 Big Mistakes in Forbes' Attack on Prince Alwaleed". Jeffrey Towson. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sylt, Christian (16 March 2013). "Saudi Prince to Fight Forbes Over Rich List". The Sunday Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Holliday, Josh (6 June 2013). "Saudi prince launches libel action against Forbes magazine over Rich List". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Dolan, Kerry (20 June 2013). "Is Prince Alwaleed Trying To Undermine The Saudi King?". Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia's Prince Alwaleed defends libel action". BBC News Online. 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ "Prince Alwaleed and Forbes settle libel case". Arabian Business.com. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ http://www.middleeastmonitor.com Article titled "Al-Waleed bin Talal supports Israel against Palestinians" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (Thursday, 29 October 2015 11:24 )

- ↑ http://www.middleeasteye.net Article titled "Fabricated quotes attributed to Saudi Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal on Israel-Palestine go viral" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (Thursday 29 October 2015 16:00 UTC)

- ↑ http://www.middleeasteye.net Article titled "Al-Waleed Bin Talal denies pro-Israel statements" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (Friday, 30 October 2015 15:10)

- ↑ Twitter message Archived 2 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. (1:11 PM - 24 Jul 2015)

- ↑ http://reform4syria.org/ Article titled "Is Al-Waleed Bin Talal Visiting Israel Or Not?" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (4 JUL 2015)

- ↑ "Saudi prince criticised for offering Bentleys to pilots bombing Yemen". Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Tigay, Chanan (15 December 2005). "Jewish groups keep watchful eye as schools receive Saudi donations - Campus Watch". www.campus-watch.org. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ "Saudi telethon raises $77 million". CNN. 7 January 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Saudi Prince Pledges $32 Billion to Good Causes, With Women's Rights a Focus". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ "$10 Million? NYC Says No Thanks". CBS. 18 September 2001. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "New York Rejects Saudi Millions,". BBC News. 12 October 2001. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ "Big Bad Apple". Al Ahram Weekly. 18–24 October 2001. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ "Saudi Gives $20 Million to Georgetown". Washington Post. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ "Saud to improve Islamic studies". Times Higher Education. 8 May 2008. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "AUB - CASAR - Home". Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "The HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud Institute for Computational Biomedicine". New York City: Weill Cornell Medical College. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ↑ Centre of Islamic Studies, Cambridge

- ↑ "Alwaleed Islamic Studies Program". Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Centre of Islamic Studies". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ↑ First Saudi Female Pilot Lands Job With Kingdom Holding Archived 24 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine., 24 November 2004. Includes photo.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia: First woman to get pilot license - BBC News". Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Prince Al-Waleed's yacht Archived 27 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine.. Yachts.monacoeye.com (31 May 2006). Retrieved on 17 January 2014.

- ↑ – Project New Kingdom 5KR Archived 3 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.. Agent4stars.com. Retrieved on 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Morrison, Murdo (17 October 2014), "Ultimate corporate jets: Nine private aircraft that combine business with pleasure", Flightglobal, Reed Business Information, archived from the original on 19 October 2014, retrieved 17 October 2014

- ↑ "Prince Alwaleed tops first Saudi Rich List". Arabian Business. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 1 September 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ↑ "Prince Alwaleed: The Prince And The Portfolio". Time. 1 December 1997. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Medals Received by Al waleed bin Talal". Al Waleed official website. 2002. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Prince Alwaleed bin Talal". Arab Bankers Association of North America. 2 December 2002. Archived from the original on 11 May 2005. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Presidencymaldives.gov". Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Maldives president awarded highest honour of Palestine". Haveeru Online. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "BCIU Gala". bciu.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012.

- ↑ "Prince Alwaleed bin Talal receives Bahrain Medal of the First Order". Saudi Gazette. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ "साउदी राजकुमारलाई नेपालले उतै तक्मा पठायो". Nagarik News. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Alwaleed awarded Colina De Boe medal". Saudi Gazette. 27 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone to decorate Saudi Prince with its Highest National Honours". Awareness Times. 10 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ "REPUBLIC DAY – HONOURS AND AWARDS 2014". Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Ordonnance Souveraine n° 5.539 du 29 octobre 2015

- 1 2 Royal Saudi couple’s divorce is 'amicable' Richard Johnson. Page Six. NYPost.com November 20, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2015

- ↑ "Khaled Bin Alwaleed Bin Talal Al Saud Biography". Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Daughters and sons of King Saud". King Saud net. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Kapoor, Talal (1 August 2007). "Wedding of the century: Rim bint al-Walid and Abdulaziz bin Musa'id". Datarabia. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ "Richest man outside U.S. enjoys life in tents". Honolulu (Hawaii) Advertiser. 21 May 2000. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ "Egyptian tycoon, Saudi princess locked in legal battle". Gulf News. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ "Saudi Gazette/ Home Page". www.saudigazette.com.sa. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014.

- 1 2 سعد الله الجابري Archived 4 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. مركز الشرق العربي

Further reading

- John Rossant, The Prince: A Biography of Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal (HarperCollins, 2001) ISBN 0-68-816457-9

- Riz Khan, Alwaleed: Businessman, Billionaire, Prince (HarperCollins, 2005) ISBN 0-06-085030-2