Alcázar of Seville

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

Patio de la Montería courtyard | |

| Location | Seville, Spain |

| Part of | Cathedral, Alcázar and General Archive of the Indies in Seville |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 383-002 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Coordinates | 37°23′02″N 5°59′29″W / 37.38389°N 5.99139°W |

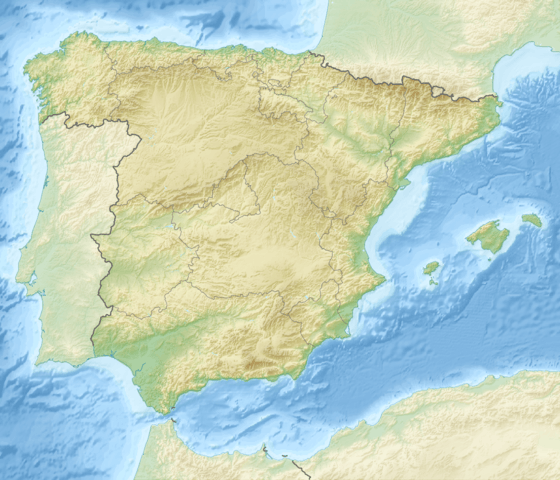

Location of Alcázar of Seville in Spain | |

The Alcázar of Seville (pronounced [alˈkaθaɾ]; Spanish: Reales Alcázares de Sevilla or "Royal Alcazars of Seville") is a royal palace in Seville, Spain, built for the Christian king Peter of Castile.[1] It was built by Castilian Christians on the site of an Abbadid Muslim residential fortress[2][3] destroyed after the Christian conquest of Seville.[4] Although some elements of other civilizations remains. The palace, a preeminent example of Mudéjar architecture in the Iberian Peninsula, is renowned as one of the most beautiful. The upper levels of the Alcázar are still used by the royal family as their official residence in Seville, and are administered by the Patrimonio Nacional. It is the oldest royal palace still in use in Europe, and was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with the adjoining Seville Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies.[5]

Etymology

The term Alcázar comes from the Arabic al-qaṣr, ("the castle" or "the palace", اَلْقَصْر), itself derived from the Latin castrum ("castle").[6][7][8][9]

History

._Reales_Alc%C3%A1zares_de_Sevilla.jpg)

- 1-Puerta del León

- 2-Sala de la Justicia y patio del Yeso (cyan)

- 3-Patio de la Montería (pink)

- 4-Cuarto del Almirante y Casa de Contratación (cream)

- 5-Palacio mudéjar o de Pedro I (red)

- 6-Palacio gótico (blue)

- 7-Estanque de Mercurio

- 8-Jardines (green)

- 9-Apeadero

- 10-Patio de Banderas

The Real Alcázar is situated near the Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies in one of Andalusia's most emblematic areas. This plot was occupied from the 8th century BC. In the 1st century AD the collegium (College of Olearians) was built. The early Visigothic Christian basilica of Saint Vincent was built on its ruins. For the construction of the Palace of Peter of Castile some shafts and capitals of this building were reused, the only Visigothic vestige that has survived to this day.[10] The tombstone of the bishop Honorato, which was probably in this church, is currently in the cathedral.[10]

Seville was conquered by the Umayyad caliphate in the year 712. At that time the basilica was demolished to build the first military work. It seems that it was a quadrangular enclosure, fortified, and annexed to the walls. During the period of the first Taifa kingdoms, various constructions were carried out, such as stables and warehouses, which should not have altered the building as a whole. The citadel began to gain importance in the first half of the 12th century, under the Abbadid dynasty, when the space doubled due to the construction of a large palace called Al-Muwarak, under the current Patio de la Monteria, of which only some archaeological remains are preserved.[10]

Under the Almohads, during the caliphate of Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, new buildings for the residence of the Caliph and his court were erected. With the exception of the walls, the previous buildings were demolished, and were carried out up to a total of twelve palaces. In the place where the Patio de la Montería is located, on the foundations of the Abbadid palace, a large building was built, which seems to be organized around a patio that followed the same scheme of the courtyard of the Aljafería of Zaragoza. Today, a sabat, or private passage, remains next to the south façade of the cathedral, which coincides with the Quibla wall of the mosque; this access allowed the caliph to reach the Macsura to avoid any danger. That palace had its royal room. A small courtyard, the Patio del Yeso, served as the residence of Pedro I in 1358 before the construction of his new palace; in spite of several restorations it is the most significant preserved space of the Almohad alcázar.[10]

The rest of the architecture of the palace, which includes its most flamboyant parts, covers almost the whole set built by Alfonso X of Castile and Peter of Castile, with Mudéjar, Gothic and Mannerist halls and courtyards.

Some gardens have Renaissance statues. After damage by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, that façade of the Palacio Gótico overlooking the Patio del Crucero was completely renovated in Baroque style.

The palace was the birthplace of Infanta Maria Antonietta of Spain (1729-1785), daughter of Philip V of Spain and Elisabeth Farnese, when the king was in the city to oversee the signing of the Treaty of Seville (1729) which ended the Anglo-Spanish War (1727).

The Palace

Puerta del León

The main entrance to the Alcázar takes its name from the 19th century tile-work inlaid above it, a crowned lion holding a cross in its claws and bearing a Gothic script.

Patio de las Doncellas

The name, meaning "The Courtyard of the Maidens", refers to the legend that the Moors demanded 100 virgins every year as tribute from Christian kingdoms in Iberia.

The lower level of the Patio was built for King Peter of Castile and includes inscriptions describing Peter as a "sultan". Various lavish reception rooms are located on the sides of the Patio. In the center is a large, rectangular reflecting pool with sunken gardens on either side. For many years, the courtyard was entirely paved in marble with a fountain in the center. However, historical evidence showed the gardens and the reflecting pool were the original design and this arrangement was restored. However, soon after this restoration, the courtyard was temporarily paved with marble once again at the request of movie director Ridley Scott. Scott used the paved courtyard as the set for the court of the King of Jerusalem in his movie Kingdom of Heaven. The courtyard arrangement was converted once more after the movie's production.

The upper story of the Patio was an addition made by Charles V. The addition was designed by Luis de Vega in the style of the Italian Renaissance although he did include both Renaissance and mudéjar plaster work in the decorations. Construction of the addition began in 1540 and ended in 1572.

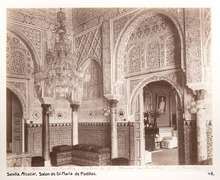

Los Baños de Doña María de Padilla

The "Baths of Lady María de Padilla" are rainwater tanks beneath the Patio del Crucero. The tanks are named after María de Padilla, the mistress of Peter the Cruel.

Salon de Embajadores

The Salon de Embajadores, meaning The Ambassadors Reception Room", was the main room that King Peter of Castile used for his stay at the Alcazar. This room was the most richly decorated within the entire Alcazar Palace, which was in keeping with its role of power. In 1526, Emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal celebrated their marriage in this room.[11]

Other sections

- Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls)

- Patio de la Montería (Courtyard of the Montería)

- Dormitorio de los Reyes Moros (Bedroom of the Moorish Kings)

- Sala de Justicia (Justice room)

- Patio del Yeso (Courtyard of the Plaster)

- Cuarto del Almirante (Admiral's Room)

- Casa de Contratación (Casa de Contratación)

- Patio del Crucero (Courtyard of the Crossing)

- Palacio Mudéjar or de Pedro I (Mudéjar Palace or that of Peter of Castile)

- Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls)

- Cuarto del Príncipe (Prince's Room)

- Patio de las Doncellas (Courtyard of the Maidens)

- Salón del Techo de Carlos V (Charles V Ceiling Room)

- Salón de Embajadores (Ambassadors' Room)

- Salón del Techo de Felipe II (Philip II Ceiling Room)

- Primera planta (First level of the Palace of Peter of Castile)

- Palacio Gótico (Gothic Palace)

- Capilla (Chapel)

- Gran Salón (Big Room)

- Salón de los Tapices (Tapestries' Room)

- Sala de las Bóvedas (Vaults' Room)

- Upper floors belong to the Patrimonio Nacional and are occupied by the royal family when visiting Seville. There are many security measures for visitors; admission is approximately 5 euros.

- Vestíbulo or Saleta de la Reina Isabel la Católica (Lobby or Queen Isabella the Catholic Monarch's Room)

- Anteortaorio de Isabel la Católica (Pre-oratory of Isabella the Catholic Monarch)

- Oratorio de Isabel la Católica (Oratory of Isabella the Catholic Monarch)

- Alcoba Real (Royal Alcove)

- Antecomedor (Pre-dining Room)

- Comedor de Gala (Gala Dining)

- Sala de fumar (Smoking Room)

- Retrete del Rey (King's Toilet)

- Antecomedor de familia, antiguo Cuarto del Rey (Family Pre-dining Room, former King's Room)

- Comedor de Familia or Cuarto Nuevo (Family Dining Room or New Room)

- Mirador de los Reyes Católicos (Viewpoint of the Catholic Monarchs)

- Dormitorio del Rey Don Pedro, antiguo Cuarto de los Lagartos (King Don Peter of Castile's Bedroom, former Lizards' Room)

- Despacho de Juan Carlos I (Juan Carlos I's Office)

- Cámara de Audiencias (Hearings' Chamber)

- Dormitorio de Isabel II (Isabella II's Bedroom)

- Colección Carranza (a museum of old azulejos)

- Gardens

- Estanque de Mercurio (Mercury Pond)

- Galería de Grutesco (Grotesque Gallery)

- Jardín de la Danza (Dance's Garden)

- Jardín de Troya (Troy's Garden)

- Jardín de la Galera (The Galley's Garden)

- Jardín de las Flores (Flowers' Garden)

- Jardín del Príncipe (Prince's Garden)

- Jardín de las Damas (Ladies' Garden)

- Pabellón de Carlos V (Charles V's Pavilion)

- Cenador del León (Lion's Gloriette)

- Jardín Inglés (English Garden)

- Jardín del Marqués de la Vega-Inclán (Marquis of la Vega-Inclán's Garden)

- Jardín de los Poetas (The Poets' Garden)

- Apeadero (Mounting-block)

- Patio de Banderas (Flags' Courtyard)

- Walls of the Alcázar

The Gardens

All the palaces of Al Andalus had garden orchards with fruit trees, horticultural produce and a wide variety of fragrant flowers. The garden-orchards not only supplied food for the palace residents but had the aesthetic function of bringing pleasure. Water was ever present in the form of irrigation channels, runnels, jets, ponds and pools.

The gardens adjoining the Alcázar of Seville have undergone many changes. In the 16th century during the reign of Philip III the Italian designer Vermondo Resta introduced the Italian Mannerist style. Resta was responsible for the Galeria de Grutesco (Grotto Gallery) transforming the old Muslim wall into a loggia from which to admire the view of the palace gardens.

In popular culture

- In 1962 the Alcázar was used as a set for Lawrence of Arabia.[12]

- The Patio de las Doncellas was used as the set for the court of the King of Jerusalem in the 2005 movie Kingdom of Heaven.

- Part of the fifth season of Game of Thrones was shot in several locations in the province of Seville, including the Alcázar.

See also

References

- ↑ Joseph F. O'Callaghan (15 April 2013). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. p. 692. ISBN 978-0-8014-6871-1.

- ↑ Frederick Alfred De Armas (1996). Heavenly Bodies: The Realms of La Estrella de Sevilla. Bucknell University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8387-5308-8.

- ↑ Titus Burckhardt (1997). Moorish Culture in Spain. Suhail Academy. p. 104.

- ↑ Antonio Urquízar-Herrera (11 May 2017). Admiration and Awe: Morisco Buildings and Identity Negotiations in Early Modern Spanish Historiography. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-879745-6.

- ↑ "Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias in Seville". UNESCO. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ The Islamic Review. Woking Muslim Mission and Literary Trust. 1960. p. 2.

- ↑ T.W. Haig (1993). M. Th. Houtsma, A.J. Wensinck, T.W. Arnold, W. Heffening, É. Lévi-Provençal, eds. E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. IV (Reprint of 1913 ed.). BRILL. p. 802. ISBN 90-04-09790-2.

- ↑ Muḥammad ibn ʻUmar Ibn al-Qūṭīyah; David James (2009). Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn Al-Qūṭīya : a Study of the Unique Arabic Manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, with a Translation, Notes, and Comments. Taylor & Francis. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-415-47552-5.

- ↑ Jonathan Bloom; Sheila Blair (14 May 2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. OUP USA. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Miguel Ángel Tabales Rodríguez (2001), "La transformación palatina del Alcázar de Sevilla, 914-1366" (PDF), Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa (12), pp. 195–213 ISSN 1130-9741

- ↑ Giordano, Carlos; Palmisano, Nicolás; Caruncho, Daniel R. (2016). Real Alcázar de Sevilla : más de mil años de arte y arquitectura. Barcelona: Dos de Arte Ediciones. ISBN 9788491030423. OCLC 946119342.

- ↑ Internet, Unidad Editorial. "El día que Lawrence de Arabia cambió el desierto por Sevilla". www.elmundo.es. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alcázar of Seville. |

- InFocus: Alcázar of Seville (Sevilla, Spain) at HitchHikers Handbook

- Images of the Alcázar in Seville – 105 images with good descriptions of the Alcázar and its history.

- Casa de la Contratación – in depth historical article.

- El Real Alcázar de Sevilla (In Spanish, English and French)

- UNESCO World Heritage

- interiors and details pictures of Seville Alcazar