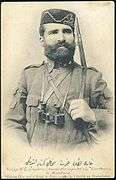

Ahmed Niyazi Bey

| Ahmed Niyazi Bey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1873 Resne, Ottoman Empire (present-day Republic of Macedonia) |

| Died |

1913 (aged 39) Vlorë, Albania |

| Occupation | Bey, Army captain (kolağası) and revolutionary |

Ahmed Niyazi Bey (1873 – 1913), (Turkish: Resneli Niyazi Bey, Ahmet Niyazi Bey; Albanian: Ahmet Njazi Bej Resnja; "Ahmet Niyazi Bey from Resen"), was the Ottoman bey of the Resne (now Resen, Republic of Macedonia) area in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[1] An ethnic Albanian,[2][3][4] he was a member of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution.[5] Niyazi is also known for the Saraj, a French-style estate he built in Resne.[6]

Life

Ahmed Niyazi Bey was born to a notable landowning family of Resne[7] and was a Tosk Albanian.[8] During his youth he completed secondary schooling in Monastir (modern Bitola) and later studied at the Ottoman War Academy (Harbiye).[9][7] He was trained by the German military and Niyazi like many of his fellow Ottoman officers held Germanophile sentiments.[10] While studying in Istanbul, he became exposed to patriotic works of liberals such as Namık Kemal which questioned the absolutism of the sultan that according to Niyazi "lit a flame" for him.[9] Niyazi fought with distinction during the Greco-Turkish War (1897).[7]

After the war he was sent home serving in the army and became renown for the effective pursuit of bandits in mountainous terrain.[7] Military service and a deteriorating security situation in Macedonia affected individuals such as Niyazi who felt that the plight of local Muslims was little known and like other peoples in the region had experienced attacks due to guerilla activity.[9] Coming from an area where the strongest supporters of the Young Turks among Albanians in the Balkans originated from central and southern Macedonia, those events motivated him to join the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).[11] He became an army captain (kolağası)[2] stationed in his birthplace of Resne and had a reputation of being an Albanian with close connections to other Albanians living in Macedonia.[12]

Young Turk Revolution (1908)

| “ | I explained that our working for the goal of justice would assure absolute equality because we are all brothers, the Turk, Albanian, Bulgarian, Greek, Vlach, Serb. | ” |

| — Ahmet Niyazi Bey, 1908, [13] | ||

Niyazi was an important member of the councils held by the Young Turks.[5] In July a CUP conspiracy involving Niyazi was uncovered by the military mufti of the Ottoman Third Army stationed in Monastir.[15] The mufti, a palace spy and police agent was shot and wounded to stop him from reporting back to Istanbul.[15] A military commission was sent from Istanbul to investigate subversion within the army in the area.[16] Fearing discovery[16] on July 3, 1908 while some officers were attending Friday prayers, Niyazi along with mayor Hoca Cemal Efendi and two hundred men raided the military depot seizing the arms, ammunition and treasury of the Resne garrison.[17][2][15] All escaped from Resne into the nearby mountains from where Niyazi initiated the Young Turk Revolution and issued a proclamation that called for the restoration of the constitution of 1876 without mentioning the CUP.[5][2][18]

During the same time, Major Ismail Enver Bey, a CUP member went into the mountains near Resne and other officers followed their example by going into the hills and formed guerilla bands (çetes).[2] No order had come from the Young Turk (CUP) committee in Salonica and instead the uprising developed spontaneously as news spread from one Ottoman army unit to another and among the various local CUP committees.[5] For the revolt to get local support Niyazi and Enver played on fears of possible foreign intervention.[2] Niyazi's reasons for going against the sultan was to defend liberty, initiate reforms for both Muslims and Christians and was of the view that "Rather than live basely, i have preferred to die... either death or the salvation of the fatherland".[5] To deal with Niyazi and other guerilla bands formed by deserting Ottoman soldiers sultan Abdul Hamid II sent general Şemsi Pasha to Resne, however on his way he was shot by an Ottoman officer in Monastir.[19][18]

During the revolution Niyazi placed his efforts on mobilizing and working with Albanians for the cause such as his comrades in the army and recruited prominent individuals like Çerçiz Topulli whom he regarded as "the Chief of the Tosk Committee of Albanians".[2][20] During those attempts to secure Albanian support Niyazi noted that Albanians complained about Turks focusing on their own nationalist interests.[19] In Albanian inhabited territories Niyazi visited Elbasan, Korçë, Debar and Ohrid while his revolutionary methods involved expelling Ottoman officials, tax collectors and creating Albanian militia to maintain order.[5] The Albanian committee of Korçë lent its support to Niyazi and at the request of the CUP it called on guerillas based in the mountains around Korçë to join Ottoman insurgent bands.[5] On July 23 the Albanian committee of Ohrid followed through with guerilla leaders Topulli and Mihal Grameno meeting Niyazi at Resen who expressed his gratitude and viewed the declaration of the CUP constitution as advantageous for the Albanian nation.[5] Niyazi also worked to recruit other Muslim guerilla bands to the revolutionary cause.[20] During the revolution the guerilla bands of both Niyazi and Enver were Muslim (mostly Albanian) paramilitaries.[21] Topulli's guerilla band gave important support to Niyazi and his forces during their capture of the Resne garrison and was a small military victory in the campaign to oust the Hamidian regime.[22] In the third week of the revolution during July, Niyazi and Enver got like minded officials and civilian notables to send multiple petitions to the Ottoman place.[18] Activists in Kosovo organised a large demonstration in support of Niyazi and the wider anti-Hamidian opposition.[23]

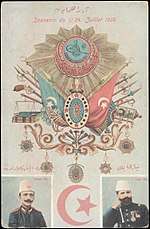

Niyazi Bey, post 1908

Niyazi Bey, post 1908- Niyazi Bey between 1908-1909

Niyazi Bey (seated in centre) with other CUP members

Niyazi Bey (seated in centre) with other CUP members Niyazi Bey, post 1908

Niyazi Bey, post 1908 Niyazi Bey (seated, centre left) with Bulgarian revolutionaries

Niyazi Bey (seated, centre left) with Bulgarian revolutionaries

Post revolution

In the aftermath of the revolution Niyazi and Enver remained in the political background due to their youth and junior military ranks with both agreeing that photographs of them would not be disturbed to the general public, however this decision was rarely observed.[24] Instead Niyazi and Enver as leaders of the revolution elevated their positions into near legendary status with their images placed on postcards and distributed throughout the Ottoman state.[25] As the actions of both men carried the appearance of initiating the revolution, Niyazi, an Albanian and Enver, a Turk (with Albanian heritage on his mother's side[26]) later got popular acclaim as "heroes of freedom" (hürriyet kahramanları) and symbolized Albanian-Turkish cooperation.[27]

Soon after the success of the revolution, Niyazi attempting to raise hopes for the new order condemned the former Hamidian regime in a speech delivered in Resne and published in a pamphlet during 1908.[28] Niyazi warned his audience about the risks of Macedonia and Anatolia becoming colonies of other countries like former Ottoman territories.[29] In 1908 the CUP committee held its congress at the conclusion of the revolution and agreed to publish Niyazi's memoirs as a book which appeared toward the end of the year.[2] The Committee wanted Niyazi to exaggerate the role the CUP played in the revolution and give the appearance that they directed all actions during those events.[2] Niyazi's memoirs highlighted the contributions of Albanians during the revolution for its success and his efforts to gain their support.[2]

In the aftermath of the revolution, CUP unity gave way to personal rivalries which by March 1909 rumor had it that Niyazi had fallen out with the main views of the Young Turks and began to have a liberal outlook regarding the situation in Macedonia.[30] He was a CUP member till his death and never managed to generate a considerable following among prominent and other rank CUP members apart from his involvement during the revolution.[30] During 1909, a group of mainly Albanian soldiers stationed in Istanbul attempted a Ottoman countercoup to undo the 1908 revolution.[31] The Ottoman Third Army, stationed in Macedonia and led by Mahmud Shevket Pasha was joined by Niyazi who brought 1,800 men from Resne.[31][32][33] Together in military operations that were directed by a fellow Albanian Ali Pasha Kolonja they retook Istanbul (April 23) with little resistance from the mutineers and deposed the sultan.[31] By 1911 Niyazi still remained in Resne and barely hid his exasperation at the deteriorating security situation in Macedonia related to fighting between guerilla bands and Ottoman forces.[34]

He was a Mücahit-i Muhterem (honoured fighter) and, in his dual capacity as hero of the constitutional revolution and revered member of the CUP, was a key figure throughout the whole Macedonian tour. During the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), Niyazi and his regiment remained until the end of the conflict and later during April 1913 arrived in Vlorë to board a ferry departing for Istanbul where he was shot by four men on the port docks.[35] No one claimed responsibility for his death while rumors of the time speculated that either someone having a personal vendetta, an Albanian nationalist or a CUP rival ordered the assassination.[35]

The Saraj of Resen, built by Niyazi Bey in the early 1900s

The Saraj of Resen, built by Niyazi Bey in the early 1900s View of the house of Niyazi Bey in Resen 1909

View of the house of Niyazi Bey in Resen 1909

Ismail Hakki Bey, an Albanian national awakening figure was the brother in law of Niyazi.[36]

In the late Ottoman period Niyazi desired to have a French-style estate, perhaps after receiving a postcard of Versailles.[6] Construction of the Saraj began in 1905 and the exterior of the building was completed in 1909 after the Young Turk Revolution.[6] As he died in Albania, Niyazi never lived to see his estate completed.[37]

Cultural references

_street_in_Resen.jpg)

As a tribute to his role in the Young Turk Revolution that began the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire, Niyazi is mentioned along with Enver in the March of the Deputies (Turkish: Mebusan Marşı or Meclis-i Mebusan Marşı), the anthem of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Ottoman parliament.[38][39] It was performed in 1909 upon the opening of the parliament.[38][39] The fourth line of the anthem reads "Long live Niyazi, long live Enver" (Turkish: "Yaşasın Niyazi, yaşasın Enver").[39]

See also

- Enver Pasha, his fellow revolutionary

- Saraj (Resen), his residence

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ahmed Niyazi Bey. |

- ↑ "Фотографот Цуле отиде по трагите на грофицата Рене". ПРИКАЗНА ЗА САРАЈОТ И ЉУБОВТА НА ДУЉАНОВИ ОД РЕСЕН. Вечер. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gawrych 2006, p. 150.

- ↑ Kedourie, Sylvia (2000). Seventy-five years of the Turkish Republic. Psychology Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7146-5042-5. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ↑ Hanioglu, M. Sükrü (2011). Atatürk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-691-15109-0. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Skendi 1967, pp. 340–341.

- 1 2 3 Grčev 2002, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Kansu, Aykut (1995). 1908 devrimi =: Elusive transformation: The revolution of 1908 in Turkey (PDF). İletişim. p. 122. ISBN 9789754705096.

- ↑ Blumi 2011, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Gingeras 2016, p. 31.

- ↑ McMeekin, Sean (2012). The Berlin-Baghdad Express. Harvard University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780674058538.

- ↑ Gingeras 2016, pp. 31, 66–67.

- ↑ Gingeras 2016, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 140.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 153. "A heavy presence of Albanians was noted in units claimed by the CUP as their own: "In the available photographs of 'national battalions' and the local bands that had joined them, Albanians with white fezes overwhelmingly outnumbered all others." (See for example, the book cover.)"

- 1 2 3 Palmer, Alan Warwick (1994). The decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire. M. Evans. p. 200. ISBN 9780871317544.

- 1 2 Macfie, Alexander Lyon (2014). Ataturk. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781317897354.

- ↑ Hale 2013, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 Gingeras 2016, p. 33.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 151.

- 1 2 Gingeras 2016, p. 32.

- ↑ Gingeras, Ryan (2014). Heroin, Organized Crime, and the Making of Modern Turkey. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780198716020.

- ↑ Blumi 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans, Alternative Balkan Modernities: 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 147. ISBN 9780230119086.

- ↑ Hale, William (2013). Turkish Politics and the Military. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 9781136101403.

- ↑ Gingeras 2016, p. 34.

- ↑ Mazaower, Mark "Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950."

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 150, 169.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 154.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 155.

- 1 2 Gingeras 2016, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Skendi 1967, pp. 364–365.

- ↑ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 167. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ↑ Gingeras 2016, p. 37.

- ↑ Gingeras 2016, p. 55.

- 1 2 Gingeras, Ryan (2016). Fall of the Sultanate: The Great War and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1908-1922. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780191663581.

- ↑ Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 355. ISBN 9781400847761.

- ↑ Grčev, Kokan (2002). "Ресенскиот "Сарај" - Историски и стилски контекст". Le Folklore macédonien. 30 (60–61): 43.

- 1 2 Güçlü, Yücel (2018). The Armenian Events Of Adana In 1909: Cemal Pasa And Beyond. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 121. ISBN 9780761869948.

- 1 2 3 Böke, Pelin; Tınç, Lütfü (2008). Son Osmanlı Meclisi'nin son günleri. Doğan Kitap. p. 22. ISBN 9789759918095.