Acer negundo

| Acer negundo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Sapindaceae |

| Genus: | Acer |

| Species: | A. negundo |

| Binomial name | |

| Acer negundo | |

| |

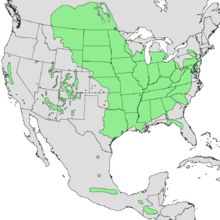

| Native range of Acer negundo | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Acer negundo is a species of maple native to North America. In Canada it is commonly known as Manitoba maple and occasionally as elf maple. Box elder, boxelder maple, ash-leaved maple, and maple ash are its most common names in the United States; in the United Kingdom and Ireland it is also known as ashleaf maple.[3]

Common names

Indicative of its familiarity to many people over a large geographic range, A. negundo has numerous common names. The names "box elder" and "boxelder maple" are based upon the similarity of its whitish wood to that of boxwood and the similarity of its pinnately compound leaves to those of some species of elder.[4] This is the only North American maple with compound leaves, though several Asian species also have them.[5]

Other common names are based upon this maple's similarity to ash, its preferred environment, its sugary sap, a description of its leaves, its binomial name, and so on. These names include (but are not limited to) ash-, cut-, or three-leaf (or -leaved) maple; ash maple; sugar ash; Negundo maple; and river maple.[6] In Canada it is commonly known as Manitoba maple and occasionally as elf maple.[7] In Russia it is called American maple (Russian: америка́нский клён, tr. amerikansky klyon) as well as ash-leaf maple (Russian: клён ясенели́стный, tr. klyon yasenelistny), and in Italian acero americano.[8]

Common names may also designate a particular subspecies. For example, a common name for A. negundo subsp. interius may be preceded by "inland" (as in "inland boxelder maple"). A common name for A. negundo subsp. californicum may be preceded by "California" or "western".

Description

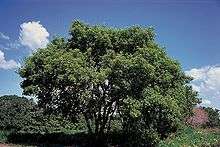

Acer negundo is a usually fast-growing and fairly short-lived tree that grows up to 10–25 meters (35–80 ft) tall, with a trunk diameter of 30–50 centimeters (12–20 in), rarely up to 1 meter (3.3 ft) diameter. It often has several trunks and can form impenetrable thickets.[9]

The shoots are green, often with a whitish to pink or violet waxy coating when young. Branches are smooth, somewhat brittle, and tend to retain a fresh green colour rather than forming a bark of dead, protective tissue. The bark on its trunks is pale gray or light brown, deeply cleft into broad ridges, and scaly.[5]

Unlike most other maples (which usually have simple, palmately lobed leaves), Acer negundo has pinnately compound leaves that usually have three to seven leaflets. Simple leaves are also occasionally present; technically, these are single-leaflet compound leaves. Although some other maples (such as Acer griseum, Acer mandshuricum and the closely related A. cissifolium) have trifoliate leaves, only A. negundo regularly displays more than three leaflets.

The leaflets are about 5–10 centimeters (2–4 in) long and 3–7 centimeters (1 1⁄4–2 3⁄4 in) wide with slightly serrate margins. Leaves have a translucent light green color and turn yellow in the fall.

The flowers are small and appear in early spring on drooping racemes 10–20 centimeters (4–8 in) long. The fruits are paired samaras, each seed slender, 1–2 centimeters (1⁄2–3⁄4 in) long, with a 2–3 centimeters (3⁄4–1 1⁄4 in) incurved wing; they drop in autumn or they may persist through winter. Seeds are usually both prolific and fertile.

Unlike most other maples, A. negundo is fully dioecious and both a male and female tree are needed for either to reproduce.

- Winter buds: Terminal buds acute, an eighth of an inch long. Lateral buds obtuse. The inner scales enlarge when spring growth begins and often become an inch long before they fall.

- Flowers: April, before the leaves, yellow green; staminate flowers in clusters on slender hairy pedicels one and a half to two inches long. Pistillate flowers in narrow drooping racemes.

- Calyx: Yellow green; staminate flowers campanulate, five-lobed, hairy. Pistillate flowers smaller, five-parted; disk rudimentary.

- Corolla: Wanting.

- Stamens: Four to six, exserted; filaments slender, hairy; anthers linear, connective pointed.

- Pistil: Ovary hairy, borne on disk, partly enclosed by calyx, two-celled, wing-margined. Styles separate at base into two stigmatic lobes.

- Fruit: Maple keys, full size in early summer. Borne in drooping racemes, pedicels one to two inches long. Key an inch and a half to two inches long, nutlets diverging, wings straight, or incurved. September. Seed half an inch long. Cotyledons, thin, narrow.[5]

Taxonomy

Subspecies

Acer negundo is often discussed as comprising three subspecies, each of which was originally described as a separate species. These are:

- A. negundo subsp. negundo is the main variety and the type to which characteristics described in the article most universally apply. Its natural range is from the Atlantic Coast to the Rocky Mountains.[9]

- A. negundo subsp. interius has more leaf serration than the main species and a more matte leaf surface. As the name interus indicates, its natural range of Saskatchewan to New Mexico is sandwiched between that of the other two subspecies.[9]

- A. negundo subsp. californicum has larger leaves than the main species. Leaves also have a velvety texture which is essential to distinguish it from A. negundo subsp. negundo. It is found in parts of California and Arizona.[9]

Some authors further subdivide subsp. negundo into a number of regional varieties but these intergrade and their maintenance as distinct taxa is disputed by many. Even the differences between recognized subspecies are probably a matter of gradient speciation.

Finally, note that a few botanists treat boxelder maple as its own distinct genus (Negundo aceroides) but this is not widely accepted.

Distribution

As noted, varieties thrive across the United States and Canada. It may also be found as far south as Guatemala.

Although native to North America, it is considered an invasive species in some areas of that continent. It can quickly colonize both cultivated and uncultivated areas and the range is therefore expanding both in North America and elsewhere. In Europe where it was introduced in 1688 as a park tree it is able to spread quickly in places and is considered an invasive species in parts of Central Europe (Germany and the Czech Republic, middle Danube, Vistula river valley in Poland) where it can form mass growth in lowlands, disturbed areas and riparian biomes on calcareous soils. It has also become naturalized in eastern China[9] and can be found in some of the cooler areas of the Australian continent where it is listed as a pest invasive species.

Ecology

This species prefers bright sunlight. It often grows on flood plains and other disturbed areas with ample water supply, such as riparian habitats. Human influence has greatly favoured this species; it grows around houses and in hedges, as well as on disturbed ground and vacant lots.

Several birds and some squirrels feed on the seeds. The evening grosbeak uses them extensively. The Maple Bug (also known as the Boxelder Bug) lays its eggs on all maples, but prefers this species. The rosy maple moth (Dryocampa rubicunda) also lays its eggs on the leaves of maple trees, including the boxelder maple, so when the larvae hatch, they feed on the leaves, which in very dense populations can cause defoliation.[10]

Cultivation

Although its weak wood, irregular form, and prolific seeding might make it seem like a poor choice for a landscape tree, A. negundo is one of the most common maples in cultivation and many interesting cultivars have been developed, including:[9]

- 'Auratum' – yellowish leaves with smooth undersides

- 'Aureomarginatum' – creamy yellow leaf margins

- 'Baron' – Hardier & seedless variety

- 'Elegans' – distinctively convex leaves

- 'Flamingo' – pink and white variegation (very popular)

- 'Pendulum' – with weeping branches.

- 'Variegatum' – creamy white leaf margins

- 'Violaceum' – younger shoots and branches have bluish colour

Uses

Although its light, close-grained, soft wood is considered undesirable for most uses, this tree has been considered as a commercial source of wood fiber, for use in fiberboard.

There is some commercial use of the tree for various decorative applications, such as turned items (bowls, stem-ware, pens). Primarily burl wood and injured wood, where the primary reason is this wood's reaction to injury, where the injured wood develops a red stain.

Use by Native Americans

The Navajo use the wood to make tubes for bellows.[11] The Cheyenne burn the wood as incense for making spiritual medicines,[12] and during Sun Dance ceremonies.[12] They also mix the boiled sap with shavings from the inner sides of animal hides and eat them as candy.[12][13]

The Meskwaki use a decoction of the inner bark as an emetic,[14] and the Ojibwa use an infusion of the inner bark for the same purpose.[15] The Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache dry scrapings of the inner bark and keep it as winter food, and they also boil the inner bark until sugar crystallizes out of it.[16] The Dakota also use the sap to make sugar,[17] as do the Omaha,[18][19] the Pawnee,[19] the Ponca,[19] the Winnebago,[19] and the indigenous people of Montana, who also freeze the sap and use it as a syrup[12] The Ojibwa mix the sap with that of the sugar maple and drink it as a beverage.[20]

The Cheyenne also use the wood to make bowls[21] and to cook meat.[12][13] The Keres make the twigs into prayer sticks.[22] The native peoples of Montana also use large trunk burls or knots to make bowls, dishes, drums, and pipe stems.[12]

The Dakota people and the Omaha people[19][23] make the wood into charcoal, which is used in ceremonial painting and tattooing.[17][19]

The Kiowa burn the wood from the negundo subspecies in the altar fire during the peyote ceremony,[24] and the Sioux boil the sap of this variety in the spring to make sugar.[25]

The interius subspecies is used by Cree to make sugar from the sap,[26] and the Tewa use the twigs as pipe stems.[27]

Medical impact

Toxicology

A protoxin present in the seeds of Acer negundo, the hypoglycin A, has been identified as a major risk factor for, and possibly the cause of, a disease in horses, seasonal pasture myopathy. SPM is an equine neurological disease which occurs seasonally in certain areas of North America and Europe, with symptoms including stiffness, difficulty walking or standing, dark urine and eventually breathing rapidly and becoming recumbent. Ingestion of sufficient quantities of box elder seeds or other parts of the plant results in breakdown of respiratory, postural, and cardiac muscles. The cause of SPM was unknown for centuries despite the disease being well known among affected areas and was only positively determined in the 21st century.[28][29][30] It is analogous to Jamaican vomiting sickness in humans, with both diseases sharing the same causative toxin. Ingesting Acer negundo seeds, or other parts of the plant, may therefore be toxic to humans, in large doses.

Allergenicity

Acer negundo is a severe allergen. Its pollination occurs from winter to spring, depending on latitude and elevation.[31]

Archaeological artifacts

Acer negundo was identified in 1959 as the material used in the oldest extant wood flutes from the Americas. These early artifacts, excavated by Earl H. Morris in 1931 in the Prayer Rock district of present-day Northeastern Arizona, have been dated to 620–670 CE.[32] The style of these flutes, now known as Anasazi flutes, uses an open tube and a splitting edge at one end. This design pre-dates the earliest extant Native American flute (which use a two-chambered design) by approximately 1,200 years.

References

- ↑ "Acer negundo L." NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ The Plant List

- ↑ "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-01-25. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ "DePauw Nature Park Field Guide to Trees" (PDF). DePauw University. p. 14. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- 1 2 3 Keeler, H. L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scriber's Sons. pp. 85–87.

- ↑ "Windsor Plywood". Note that some of the common names given in this reference are questionable, "stinking ash" and "black ash" typically refer to Ptelea trifoliata and Fraxinus nigra, respectively. This reference is retained as an example of the confusion which arises when plants such as A. negundo are discussed by other than their scientific names.

- ↑ "Community trees of the Prairie provinces". Natural Resources Canada. 2007-02-22. Archived from the original on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ "Acer negundo L." Schede di Botanica.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 van Gelderen, C.J. & van Gelderen, D.M. (1999). Maples for Gardens: A Color Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Dryocampa rubicunda (rosy maple moth)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- ↑ Elmore, Francis H. (1944). Ethnobotany of the Navajo. Sante Fe, NM. School of American Research (p. 62)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hart, Jeff (1992). Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples. Helena. Montana Historical Society Press (p. 4)

- 1 2 Hart, Jeffrey A. (1981). "The Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana." Journal of Ethnopharmacology 4:1–55 (p. 13).

- ↑ Smith, Huron H. (1928). "Ethnobotany of the Meskwaki Indians." Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:175–326 (p. 200)'

- ↑ Smith, Huron H. (1932). "Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians." Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee 4:327–525 (p. 353)

- ↑ Castetter, Edward F. and M. E. Opler (1936). "Ethnobiological Studies in the American Southwest III. The Ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache." University of New Mexico Bulletin 4(5):1–63 (p. 44).

- 1 2 Gilmore, Melvin R. (1913). "Some Native Nebraska Plants With Their Uses by the Dakota." Nebraska State Historical Society Collections 17:358–70 (p. 366)

- ↑ Gilmore, Melvin R. (1913). "A Study in the Ethnobotany of the Omaha Indians." Nebraska State Historical Society Collections 17:314–57. (p. 329).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gilmore, Melvin R. (1919). "Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region." SI-BAE Annual Report #33 (p. 101)

- ↑ Smith, Huron H. (1932). "Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians." Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee 4:327–525 (p. 394).

- ↑ Hart, Jeffrey A. (1981). "The Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana." Journal of Ethnopharmacology 4:1–55 (p. 46).

- ↑ Swank, George R. (1932). The Ethnobotany of the Acoma and Laguna Indians. University of New Mexico, M.A. Thesis (p. 24).

- ↑ Gilmore, Melvin R. (1913). "A Study in the Ethnobotany of the Omaha Indians." Nebraska State Historical Society Collections 17:314–57. (p. 336).

- ↑ Vestal, Paul A. and Richard Evans Schultes (1939). The Economic Botany of the Kiowa Indians. Cambridge MA. Botanical Museum of Harvard University (p. 40)

- ↑ Blankinship, J. W. (1905). "Native Economic Plants of Montana." Bozeman. Montana Agricultural College Experimental Station, Bulletin 56 (p. 16)

- ↑ Johnston, Alex (1987). Plants and the Blackfoot. Lethbridge, Alberta. Lethbridge Historical Society (p. 44).

- ↑ Robbins, W.W., J.P. Harrington and B. Freire-Marreco (1916). "Ethnobotany of the Tewa Indians." SI-BAE Bulletin #55 (p. 38).

- ↑ "Seasonal pasture myopathy". Michigan State University. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ Anna Renier. "Seasonal pasture myopathy cause identified". University of Minnesota Extension.

- ↑ Valberg, S.J.; Sponseller, B.T.; Hegeman, A.D.; Earing, J.; Bender, J.B.; Martinson, K.L.; Patterson, S.E.; Sweetman, L. (July 2013). "Seasonal pasture myopathy/atypical myopathy in North America associated with ingestion of hypoglycin A within seeds of the box elder tree". Equine Veterinary Journal. 45 (4): 419–426. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00684.x. ISSN 2042-3306.

- ↑ "Box Elder, Ash-Leaf Maple (Acer negundo)". PollenLibrary.com.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2011). "Anasazi Flutes from the Broken Flute Cave". Retrieved 2011-10-18.

Bibliography

- Philips, Roger. Trees of North America and Europe. Random House, Inc., New York ISBN 0-394-50259-0, 1979.

- Maeglin, Robert R.; Lewis F. Ohmann (1973). "Boxelder (Acer negundo): A Review and Commentary". Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 100 (6): 357–363. doi:10.2307/2484104. JSTOR 2484104.

External links

- Calflora Database: Acer negundo (Boxelder)

- Acer negundo facts and diagnostic traits

- Interactive Distribution Map of Acer negundo

- Acer negundo images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu