Cain and Abel

In the biblical Book of Genesis, Cain[lower-alpha 1] and Abel[lower-alpha 2] are the first two sons of Adam and Eve.[1] Cain, the firstborn, was a farmer, and his brother Abel was a shepherd. The brothers made sacrifices to God, each of his own produce, but God favored Abel's sacrifice instead of Cain's. Cain then murdered Abel, whereupon God punished Cain to a life of wandering. Cain then dwelt in the land of Nod (נוֹד, "wandering"), where he built a city and fathered the line of descendants beginning with Enoch.

The narrative never explicitly states Cain's motive for murdering his brother, nor God's reason for rejecting Cain's sacrifice, nor details on the identity of Cain's wife. Some traditional interpretations consider Cain to be the originator of evil, violence, or greed. According to Genesis, Cain was the first human born and Abel was the first to die.

Genesis narrative

The story of Cain's murder of Abel and its consequences is told in Genesis 4:1-18: (Translation and notes from Robert Alter, "The Five Books of Moses")[2]

1And the human knew Eve his woman and she conceived and bore Cain, and she said, "I have got me a man with the Lord." 2And she bore as well his brother Abel, and Abel became a herder of sheep while Cain was a tiller of the soil. 3And it happened in the course of time that Cain brought from the fruit of the soil an offering to the Lord. 4And Abel too had brought from the choice firstlings of his flock, and the Lord regarded Abel and his offering 5but did not regard Cain and his offering. And Cain was very incensed, and his face fell. 6And the Lord said to Cain,

"Why are you incensed,

and why is your face fallen?

7For whether you offer well,

or whether you do not,

at the tent flap sin crouches

and for you is its longing,

but you will rule over it."8And Cain said to Abel his brother, "Let us go out to the field," and when they were in the field Cain rose against Abel his brother and killed him. 9And the Lord said to Cain, "Where is Abel your brother? And he said, "I do not know: am I my brother's keeper?" 10And He said, "What have you done? Listen! your brother's blood cries out to me from the soil. 11And so, cursed shall you be by the soil that gaped with its mouth to take your brother's blood from your hand. 12If you till the soil, it will no longer give you strength. A restless wanderer shall you be on the earth." 13 And Cain said to the Lord, "My punishment is too great to bear. 14Now that You have driven me this day from the soil I must hide from Your presence, I shall be a restless wanderer on the earth and whoever finds me will kill me." 15And the Lord said to him, "Therefore whoever kills Cain shall suffer sevenfold vengeance." And the Lord set a mark upon Cain so that whoever found him would not slay him."

16And Cain went out from the Lord's presence and dwelled in the land of Nod east of Eden. 17And Cain knew his wife and she conceived and bore Enoch. Then he became the builder of a city and he called the name of the city like his son's name, Enoch."

Translation notes

- 4:1 – The Hebrew verb "knew" implies intimate or sexual knowledge, along with possession. The name "Cain", which means "smith", resembles the verb translated as "gotten" but also possibly meaning "to make".[2]

- 4:2 – Abel's name could be associated with "vapor" or "puff of air".[2]

- 4:8 – "Let us go out to the field" does not appear in the Masoretic Text, but is found in other versions including the Septuagint and Samaritan Pentateuch.[2]

- 4:10–12 – Cain is cursed min-ha-adamah, from the earth, being the same root as "man" and Adam.

Origins

Cain and Abel are traditional English renderings of the Hebrew names Qayin (קין) and Hevel (הבל). The original text did not have vowels. It has been proposed that the etymology of their names may be a direct pun on the roles they take in the Genesis narrative. Abel is thought to derive from a reconstructed word meaning "herdsman", with the modern Arabic cognate ibil now specifically referring only to "camels". Cain is thought to be cognate to the mid-1st millennium BC South Arabian word qyn, meaning "metalsmith".[3] This theory would make the names descriptive of their roles, where Abel works with livestock, and Cain with agriculture—and would parallel the names Adam ("man," אדם) and Eve ("life-giver," חוה Chavah).

The oldest known copy of the biblical narrative is from the Dead Sea Scrolls, and dates to the first century BC.[4][5] Cain and Abel also appear in a number of other texts,[6] and the story is the subject of various interpretations.[7] Abel, the first murder victim, is sometimes seen as the first martyr; while Cain, the first murderer, is sometimes seen as an ancestor of evil.[8] Some scholars suggest the pericope may have been based on a Sumerian story representing the conflict between nomadic shepherds and settled farmers.[9] Modern scholars typically view the stories of Adam and Eve and Cain and Abel to be about the development of civilization during the age of agriculture; not the beginnings of man, but when people first learned agriculture, replacing the ways of the hunter-gatherer.[10]

Cain and Abel are symbolic rather than real.[11] Like almost all of the persons, places and stories in the Primeval history (the first eleven chapters of Genesis), they are mentioned nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible, a fact that suggests that the History is a late composition attached to Genesis to serve as an introduction.[12] Just how late is a matter for dispute: the history may be as late as the Hellenistic period (first decades of the 4th century BCE),[13] but the high level of Babylonian myth behind its stories has led others to date it to the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE).[14][15] A prominent Mesopotamian parallel to Cain and Abel is the Sumerian myth of the Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzid,[14][15][16] in which the shepherd Dumuzid and the farmer Enkimdu compete for the affection of the goddess Inanna,[17] with Dumuzid (the shepherd) winning out.[18] Another parallel is Enlil Chooses the Farmer-God,[19] in which the farmer-god Emesh and the shepherd-god Enten bring their dispute over which of them is better to the chief god Enlil,[20] who rules in favor of Enten (the shepherd).[21]

Jewish and Christian interpretations

One question arising early in the story is why God rejects Cain's sacrifice, since Cain never received instructions about how to sacrifice correctly, nor had he done anything wrong, and why God then admonishes Cain with a warning about sin. The Midrash suggest that although Abel brought the best meat from his flock, Cain did not set aside for God the best of his harvest.[22]

Cain

| Cain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Spouse(s) | Awan, who was his sister[23] |

| Children | Enoch |

| Parent(s) | Adam and Eve |

| Relatives |

In Genesis: Abel (sibling) Seth (sibling) According to later traditions: Aclima (sibling) Awan (sibling) Azura (sibling) |

According to the Book of Genesis, Cain (Hebrew: קַיִן, Qayin; Koine Greek Κάιν, Ka-in;[24] Ethiopian version: Qayen; Arabic: قابيل, Qābīl) is the first child of Eve,[25] the first murderer, and the third human being to fall under a curse.[26]

According to Genesis 4:1–16, Cain treacherously murdered his brother Abel, lied about the murder to God, and as a result was cursed and marked for life. With the earth left cursed to drink Abel's blood, Cain was no longer able to farm the land. Cain is punished as a "fugitive and wanderer". He receives a mark from God, commonly referred to as the mark of Cain, representing God's promise to protect Cain from being murdered.[27]

Exegesis of the Septuagint's narrative, "groaning and shaking upon the earth" has Cain suffering from body tremors.[28] Interpretations extend Cain's curse to his descendants, where they all died in the Great Deluge as retribution for the loss of Abel's potential offspring.[29]

Etymology of name

One popular theory regarding the name of Cain connects it to the verb "kana" (קנה), meaning "to get" and used by Eve in Genesis 4:1 when she says after bearing Cain, "I have gotten a man from the Lord." In this viewpoint, articulated by Nachmanides in the thirteenth century, Cain's name presages his role of mastery, power, and sin.[30] In one of the Legends of the Jews, Cain is the fruit of a union between Eve and Satan, who is also the angel Samael and the serpent in the Garden of Eden, and Eve exclaims at Cain's birth, "I have gotten a man through an angel of the Lord."[31]

According to the Life of Adam and Eve, Cain fetched his mother a reed (qaneh) which is how he received his name Qayin (Cain). The symbolism of him fetching a reed may be a nod to his occupation as a farmer, as well as a commentary to his destructive nature. He is also described as "lustrous", which may reflect the Gnostic association of Cain with the sun.[32]

Characteristics

Cain is described as a city-builder,[33] and the forefather of tent-dwelling pastoralists, all lyre and pipe players, and bronze and iron smiths.[34]

In an alternate translation of Genesis 4:17, endorsed by a minority of modern commentators, Cain's son Enoch builds a city and names it after his son, Irad. Such a city could correspond with Eridu, one of the most ancient cities known.[35] Philo observes that it makes no sense for Cain, the third human on Earth, to have founded an actual city. Instead, he argues, the city symbolizes an unrighteous philosophy.[36]

In the New Testament, Cain is cited as an example of unrighteousness in 1 John 3:12 and Jude 1:11. The Targumim, rabbinic sources, and later speculations supplemented background details for the daughters of Adam and Eve.[37] Such exegesis of Genesis 4 introduced Cain's wife as being his sister, a concept that has been accepted for at least 1800 years.[38] This can be seen with Jubilees 4 which narrates that Cain settled down and married his sister Awan, who bore his first son, the first Enoch, approximately 196 years after the creation of Adam. Cain then establishes the first city, naming it after his son, builds a house, and lives there until it collapses on him, killing him.[39]

Other stories

In Jewish tradition, Philo, Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer and the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan asserted that Adam was not the father of Cain. Rather, Eve was subject to adultery having been seduced by either Sammael,[40][41] the serpent[42] (nahash, Hebrew: נחש) in the Garden of Eden,[43] or the devil himself.[37] Christian exegesis of the "evil one" in 1 John 3:10–12 have also led some commentators, like Tertullian, to agree that Cain was the son of the devil[44] or some fallen angel. Thus, according to some interpreters, Cain was half-human and half-angelic, one of the Nephilim. Gnostic exegesis in the Apocryphon of John has Eve seduced by Yaldaboth. However, in the Hypostasis of the Archons, Eve is raped by a pair of Archons.[45]

Pseudo-Philo, a Jewish work of the first century CE, narrates that Cain murdered his brother at the age of 15. After escaping to the Land of Nod, Cain fathered four sons: Enoch, Olad, Lizpha and Fosal; and two daughters: Citha and Maac. Cain died at the age of 730, leaving his corrupt descendants spreading evil on earth.[46] According to the Book of Jubilees, Cain murdered his brother with a stone. Afterwards, Cain was killed by the same instrument he used against his brother; his house fell on him and he was killed by its stones.[47] A heavenly law was cited after the narrative of Cain's death saying:

With the instrument with which a man kills his neighbour with the same shall he be killed ; after the manner that he wounded him, in like manner shall they deal with him.[48]

A Talmudic tradition says that after Cain had murdered his brother, God made a horn grow on his head (see the mark of Cain). Later, Cain was killed at the hands of his great grandson Lamech, who mistook him for a wild beast.[49] A Christian version of this tradition from the time of the Crusades holds that the slaying of Cain by Lamech took place on a mound called "Cain Mons" (i.e. Mount Cain), which is a corruption of "Caymont", a Crusader fort in Tel Yokneam in modern-day Israel.[50]

According to the Mandaean scriptures including the Qolastā, the Book of John and Genzā Rabbā, Abel is cognate with the angelic soteriological figure Hibil Ziwa[51] who taught John the Baptist.[52]

Abel

| Abel | |

|---|---|

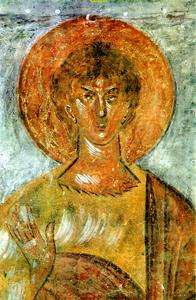

Icon of Abel by Theophanes the Greek | |

| Parent(s) | Adam and Eve |

| Relatives |

In Genesis: Cain (sibling) Seth (sibling) According to later traditions: Aclima (sibling) Awan (sibling) Azura (sibling) |

According to the narrative in Genesis, Abel (Hebrew: הֶבֶל, Hevel; Arabic: هابيل, Hābīl) is Eve's second son. His name in Hebrew is composed of the same three consonants as a root meaning "breath". Julius Wellhausen, and many scholars following him, have proposed that the name is independent of the root.[53] Eberhard Schrader had previously put forward the Akkadian (Old Assyrian dialect) ablu ("son") as a more likely etymology.[54]

In Christianity, comparisons are sometimes made between the death of Abel and that of Jesus, the former thus seen as being the first martyr. In Matthew 23:35 Jesus speaks of Abel as "righteous", and the Epistle to the Hebrews states that "The blood of sprinkling ... [speaks] better things than that of Abel" (Hebrews 12:24). The blood of Jesus is interpreted as bringing mercy; but that of Abel as demanding vengeance (hence the curse and mark).[55]

Abel is invoked in the litany for the dying in the Roman Catholic Church, and his sacrifice is mentioned in the Canon of the Mass along with those of Abraham and Melchizedek. The Alexandrian Rite commemorates him with a feast day on December 28.[56]

According to the Coptic Book of Adam and Eve (at 2:1–15), and the Syriac Cave of Treasures, Abel's body, after many days of mourning, was placed in the Cave of Treasures, before which Adam and Eve, and descendants, offered their prayers. In addition, the Sethite line of the Generations of Adam swear by Abel's blood to segregate themselves from the unrighteous.

In the Book of Enoch (22:7), regarded by most Christian and Jewish traditions as extra-biblical, the soul of Abel is described as having been appointed as the chief of martyrs, crying for vengeance, for the destruction of the seed of Cain. This view is later repeated in the Testament of Abraham (A:13 / B:11), where Abel has been raised to the position as the judge of the souls.

Family

Family tree

The following family tree of the line of Cain is compiled from a variety of biblical and extra-biblical texts.

| Adam | Eve | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cain | Abel | Seth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enoch | Enos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Irad | Kenan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mehujael | Mahalalel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methushael | Jared | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adah | Lamech | Zillah | Enoch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jabal | Jubal | Tubal-Cain | Naamah | Methuselah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lamech | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Noah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shem | Ham | Japheth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sisters

Various early commentators have said that Cain and Abel have sisters, usually twin sisters. According to Rabbi Joshua ben Karha as quoted in Genesis Rabbah, "Only two entered the bed, and seven left it: Cain and his twin sister, Abel and his two twin sisters."[57][58]

Motives

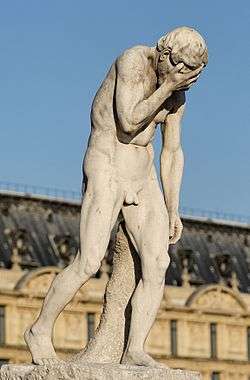

.jpg)

The Book of Genesis does not give a specific reason for the murder of Abel. Modern commentators typically assume that the motives were jealousy and anger due to God rejecting Cain's offering, while accepting Abel's.[59] The First Epistle of John says the following:

Do not be like Cain, who belonged to the evil one and murdered his brother. And why did he murder him? Because his own actions were evil and his brother’s were righteous."

Ancient exegetes, such as the Midrash and the Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan, tell that the motive involved a desire for the most beautiful woman. According to Midrashic tradition, Cain and Abel each had twin sisters; each was to marry the other's. The Midrash states that Abel's promised wife, Aclima, was more beautiful. Since Cain would not consent to this arrangement, Adam suggested seeking God's blessing by means of a sacrifice. Whoever God blessed would marry Aclima. When God openly rejected Cain's sacrifice, Cain slew his brother in a fit of jealousy and anger.[59][60] Rabbinical exegetes have discussed whether Cain's incestuous relationship with his sister was in violation of halakha.[61]

Muslim interpretation

The story appears in the Quran, in Surah 5, verses 27 to 31:[62]

[Prophet], tell them the truth about the story of Adam's two sons: each of them offered a sacrifice, and it was accepted from one and not the other. One said, 'I will kill you,' but the other said, 'God only accepts the sacrifice of those who are mindful of Him. If you raise your hand to kill me, I will not raise mine to kill you. I fear God, the Lord of all worlds, and I would rather you were burdened with my sins as well as yours and became an inhabitant of the Fire: such is the evildoers' reward.' But his soul prompted him to kill his brother: he killed him and became one of the losers. God sent a raven to scratch up the ground and show him how to cover his brother's corpse and he said, 'Woe is me! Could I not have been like this raven and covered up my brother's body?' He became remorseful.

— The Quran (English translation by M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

The story of Cain and Abel has always been used as a deterrent from murder in Islamic tradition. Abdullah ibn Mas'ud reported that Muhammad said in a hadith:

"No soul is wrongfully killed except that some of the burden falls upon the son of Adam, for he was the first to establish the practice of murder."[63]

Muslim scholars were divided on the motives behind Cain's murder of Abel, and further why the two brothers were obliged to offer sacrifices to God. Some scholars believed that Cain's motives were plain jealousy and lust. Both Cain and Abel desired to marry Adam's beautiful daughter, Aclima (Aqlimia' in Arabic). Seeking to end to the dispute between them, Adam suggested that each present an offering before God. The one whose offering God accepted would marry Aclima. Abel, a generous shepherd, offered the fattest of his sheep as an oblation to God. But Cain, a miserly farmer, offered only a bunch of grass and some worthless seeds to him. God accepted Abel's offering and rejected Cain's—an indication that Abel was more righteous than Cain, and thus worthier of Aclima. As a result, it was decided that Abel would marry Aclima. Cain, on the other hand, would marry her less beautiful sister. Blinded by anger and lust for Aclima, Cain sought to get revenge on Abel and escape with Aclima.[64][65]

According to another tradition, the devil appeared to Cain and instructed him how to exact revenge on Abel. "Hit Abel's head with a stone and kill him", whispered the devil to Cain. After the murder, the devil hurried to Eve shouting: "Eve! Cain has murdered Abel!". Eve did not know what murder was or how death felt like. She asked, bewildered and horrified, "Woe to you! What is murder?". "He [Abel] does not eat. He does not drink. He does not move [That's what murder and death are]", answered the Devil. Eve burst out into tears and started to wail madly. She ran to Adam and tried to tell him what happened. However, she could not speak because she could not stop wailing. Since then, women wail brokenheartedly when a loved one dies.[66] A different tradition narrates that while Cain was quarreling with Abel, the devil killed an animal with a stone in Cain's sight to show him how to murder Abel.[67]

After burying Abel and escaping from his family, Cain got married and had children. They died in Noah's flood among other tyrants and unbelievers.[68]

Some Muslim scholars puzzled over the mention of offerings in the narrative of Cain and Abel. Offerings and sacrifices were ordained only after the revelation of the Torah to Moses. This led some scholars, such as Said ibn al-Musayyib, to think that the sons of Adam mentioned in the Quran are actually two Israelites, not Cain and Abel.[67]

According to Shi'a Muslim belief, Abel ("Habeel") is buried in the Nabi Habeel Mosque, located on the west mountains of Damascus, near the Zabadani Valley, overlooking the villages of the Barada river (Wadi Barada), in Syria. Shi'a are frequent visitors of this mosque for ziyarat. The mosque was built by Ottoman Wali Ahmad Pasha in 1599.

Legacy and symbolism

Allusions to Cain and Abel as an archetype of fratricide appear in numerous references and retellings, through medieval art and Shakespearean works up to present day fiction.[26] A millennia-old explanation for Cain being capable of murder is that he may have been the offspring of a fallen angel or Satan himself, rather than being from Adam.[43][37][45]

A medieval legend has Cain arriving at the Moon, where he eternally settled with a bundle of twigs. This was originated by the popular fantasy of interpreting the shadows on the Moon as a face. An example of this belief can be found in Dante Alighieri's Inferno (XX, 126[69]) where the expression "Cain and the twigs" is used as a kenning for "moon".

A treatise on Christian Hermeticism, Meditations on the Tarot: A journey into Christian Hermeticism, describes the biblical account of Cain and Abel as a myth, i.e. it expresses, in a form narrated for a particular case, an "eternal" idea. It shows us how brothers can become mortal enemies through the very fact that they worship the same God in the same way. According to the author, the source of religious wars is revealed. It is not the difference in dogma or ritual which is the cause, but the "pretention to equality" or "the negation of hierarchy".[70]

In Latter-day Saint theology, Cain is considered to be the quintessential Son of Perdition, the father of secret combinations (i.e. secret societies and organized crime), as well as the first to hold the title Master Mahan meaning master of [the] great secret, that [he] may murder and get gain.[71]

In Mormon folklore — a second-hand account relates that an early Mormon leader, David W. Patten, encountered a very tall, hairy, dark-skinned man in Tennessee who said that he was Cain. The account states that Cain had earnestly sought death but was denied it, and that his mission was to destroy the souls of men.[72][73] The recollection of Patten's story is quoted in Spencer W. Kimball's The Miracle of Forgiveness, a popular book within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[74] This widespread Mormon belief is further emphasized by an account from Salt Lake City in 1963 which stated that "One superstition is based on the old Mormon belief that Cain is a black man who wanders the earth begging people to kill him and take his curse upon themselves (M, 24, SLC, 1963)."[75]

Freud’s theory of fratricide is explained by the Oedipus or Electra complex through Carl Jung's supplementation.[76]

There were other, minor traditions concerning Cain and Abel, of both older and newer date. The apocryphal Life of Adam and Eve tells of Eve having a dream in which Cain drank his brother’s blood. In an attempt to prevent the prophecy from happening the two young men are separated and given different jobs.[77]

The author Daniel Quinn, first in his book "Ishmael" and later in "The Story of B", proposes that the story of Cain and Abel is an account of early Semitic herdsmen observing the beginnings of what he calls totalitarian agriculture, with Cain representing the first 'modern' agriculturists and Abel the pastoralists.[78]

Cultural portrayals and references

- Like other prominent biblical figures, Cain and Abel appear in many works of art, including works by Titian, Peter Paul Rubens and William Blake.

- In the classic poem Beowulf, c. 1000 CE, the monstrous Grendel and his mother are said to be descended from Cain.[79]

- In William Shakespeare's Hamlet, the characters King Claudius and King Hamlet are parallels of Cain and Abel.[80] The expression "Cain-coloured beard" (Cain and Judas were traditionally considered to have red or yellow hair)[81] is used in Shakespeare's The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602).[79]

- Lord Byron rewrote and dramatized the story in the play Cain (1821), viewing Cain as symbolic of a sanguine temperament, provoked by Abel's hypocrisy and sanctimony.[79]

- Victor Hugo's poem "La Conscience" (1853, part of the La Légende des siècles collection) tells of Cain and his family fleeing from God's wrath.[82]

- John Steinbeck's 1952 novel East of Eden (also a 1955 film) refers in its title to Cain's exile and contains discussions of the Cain and Abel story which then play out in the plot.[83]

- Cain and Abel have appeared in comics since the 1950s. In 1989, Neil Gaiman made them recurring characters in his comic series The Sandman.[84]

- Bobby and J.R. Ewing in the TV series Dallas (1978) have been described as variations of Cain and Abel.[85]

- The role-playing game Vampire: the Masquerade (1991) refers to vampires as "Cainites" after Cain, who is referred to as the first vampire.[86]

- 4 Runner's song "Cain's Blood" (1995) uses Cain and Abel as a metaphor for the struggle between good and evil in the song's narrator.[87]

- A "Mark of Cain" is featured in the TV series Supernatural (2005), and Cain appears as a character.[88][89]

- The Danish stageplay Biblen (2008) discusses and reenacts various Biblical stories, including Abel's murder by Cain.[90]

- In Darren Aronofsky's allegorical film mother! (2017), the characters "oldest son" and "younger brother" represent Cain and Abel.[91]

- Cain and Abel appear on the TV series Lucifer (2016).[92]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Schwartz, Howard; Loebel-Fried, Caren; Ginsburg, Elliot K. (2004). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford University Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0195358704.

- 1 2 3 4 Alter 2008, p. 29.

- ↑ Richard S. Hess (1993). Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1–11, pp. 24–25. ISBN 3-7887-1478-6.

- ↑ (4QGenb = 4Q242) The Dead Sea Scrolls were inspected using infra-red photography and published by Jim R Davila as part of his doctoral dissertation in 1988. See: Jim R Davila, Unpublished Pentateuchal Manuscripts from Cave IV Qumran: 4QGenExa, 4QGenb-h, j-k, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1988.

- ↑ PaeleoJudaica, Davila's blog post [search for 4QGenb].

- ↑ Jubilees 4:31; Patriarchs, Benjamin 7; Enoch 22:7.

- ↑ Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses 1:7:5 (c. 180) describes (unfavourably) a Gnostic interpretation. Church Fathers, Rabbinic commentators and more recent scholars have also proposed interpretations.

- ↑ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer 21 (c. 833) and others.

- ↑ Transliteration of original language version: Dumuzid and Enkimdu at Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL) founded by Jeremy Allen Black from Oxford University. English translation at "Chapter IV. Miscellaneous myths: Inanna prefers the farmer". Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Kugel 1998, p. 54-57.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Sailhamer 2010, p. 301.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 240-241.

- 1 2 Gmirkin 2006, p. 6.

- 1 2 Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 53-54.

- ↑ Kramer 1961, p. 101.

- ↑ Kramer 1961, pp. 101–103.

- ↑ Kramer 1961, p. 103.

- ↑ Kramer 1961, p. 49.

- ↑ Kramer 1961, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Kramer 1961, p. 51.

- ↑ Doukhan 2016, p. 57, 61.

- ↑ Charlesworth, James (2010), The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 2, p. 61

- ↑ Novum Testamentum Graece (NA27): Hebrews 11:4, 1John 3:12, Jude 1:11

- ↑ Byron 2011, pp. 11, 12: Genesis 4:1.

- 1 2 Byron 2011, p. 93.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 93, 119, 121.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 98.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ Doukhan 2016, p. 59.

- ↑ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I : The Ten Generations - The Birth of Cain (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 15, 16: L.A.E. (Vita) 21:3, Trans. by Johnson.

- ↑ Genesis 4:17

- ↑ Genesis 4:19–22

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 124–125.

- ↑ Philo, Posterity of Cain lines 49–58 (from Works of Philo Judaeus, Vol. 1); quoted in Byron 2011, pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 3 Luttikhuizen 2003, p. vii.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ "Cain". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 17: "And Adam knew about his wife Eve that she had conceived from Sammael" – Tg.Ps.-J.: Gen.4:1, Trans. by Byron.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 17: "(Sammael) riding on the serpent came to her and she conceived [Cain]" - Pirqe R. L. 21, Trans. by Friedlander.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 17: "First adultery came into being, afterward murder. And he [Cain] was begotten into adultery, for he was the child of the serpent." – Gos.Phil. 61:5–10, Trans. by Isenberg.

- 1 2 Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Vol.1, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8018-5890-9, p.105–09

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 17: "Having been made pregnant by the devil ... she brought forth a son." – Tertullian, Patience 5:15.

- 1 2 Byron 2011, p. 15-19.

- ↑ Pseudo-Philo (Biblical Antiquities of Philo), chapter 1

- ↑ Jubilees 4:31

- ↑ Jubilees 4:32

- ↑ Legends of the Jews, Louis Ginzberg – Volume I

- ↑ Conder, C. R. (Claude Reignier) (1878). Tent work in Palestine. A record of discovery and adventure Vol. 1. London R. Bentley & Son. pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Drower, E.S. (1932). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Gorgias Press.com. ISBN 978-1931956499.

- ↑ "76 - Anush-Uthra and Christ". 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen, Skizzen und Vorarbeiten, volume 3, (1887), p. 70.

- ↑ Eberhard Schrader, Die Keilinschrift und das Alte Testament, 1872.

- ↑ For copies of a spectrum of notable translations and commentaries see Hebrews 12:24 at the Online Parallel Bible.

- ↑ Holweck, F. G., A Biographical Dictionary of the Saints. St. Louis, MO: B. Herder Book Co., 1924.

- ↑ Midrash Rabbah: Genesis, Volume One, translated by Rabbi Dr. H. Freedman; London: Soncino Press, 1983; ISBN 0-900689-38-2; p. 180.

- ↑ Luttikhuizen 2003, pp. 36–39.

- 1 2 Byron 2011, p. 11: Anglea Y. Kim, "Cain and Abel in the Light of Envy: A Study of the History of the Interpretation of Envy in Genesis 4:1-16," JSP (2001), p.65-84

- ↑ Brewer, E. Cobham (1978). The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (reprint of 1894 ed.). Edwinstowe, England: Avenel Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-517-25921-4.

- ↑ Byron 2011, p. 27.

- ↑ Abel. "Abel - Ontology of Quranic Concepts from the Quranic Arabic Corpus". Corpus.quran.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ↑ Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim

- ↑ Tafsir al-Qur'an al-adhim (Interpretation of the Holy Qur'an), Ibn Kathir – Surat Al-Ma'ida

- ↑ Benslama, Fethi (2009). Psychoanalysis and the Challenge of Islam. U of Minnesota Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0816648887.

- ↑ Adapted from Ibn Abul-Hatim's narrative in Tafsir al-Qur'an al-adhim and Tafsir al-Tabari, Surat Al-Ma'ida

- 1 2 Tafsir al-Qur'an al-adhim and Tafsir al-Tabari, Surat Al Ma'ida

- ↑ The Beginning and the End, Ibn Kathir – Volume I

- ↑ Dante, The Divine Comedy, Inferno, canto 20, line 126 and 127. The Dante Dartmouth Project contains the original text and centuries of commentary.

- "For now doth Cain with fork of thorns confine

- On either hemisphere, touching the wave

- Beneath the towers of Seville. Yesternight

- The moon was round."

- But tell, I pray thee, whence the gloomy spots

- Upon this body, which below on earth

- Give rise to talk of Cain in fabling quaint?"

- ↑ Anonymous, Meditations on the Tarot: A journey into Christian Hermeticism, translated by Robert Powell 1985, 2002 ed, pp14-15

- ↑ Moses 5:31

- ↑ Letter by Abraham O. Smoot, quoted in Lycurgus A. Wilson (1900). Life of David W. Patten, the First Apostolic Martyr (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News) p. 50 (pp. 46–47 in 1993 reprint by Eborn Books).

- ↑ Linda Shelley Whiting (2003). David W. Patten: Apostle and Martyr (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort) p. 85.

- ↑ Spencer W. Kimball (1969). The Miracle of Forgiveness (Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, ISBN 0-88494-444-1) pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Cannon, Anthon S., Wayland D. Hand, and Jeannine Talley. "Religion, Magic, Ghostlore." Popular Beliefs and Superstitions from Utah. Salt Lake City: University of Utah, 1984. 314. Print.

- ↑ Jens de Vlemnick (2007). Psychoanalytische Perspectieven. Vol 25 (3/4). Cain and Abel: The Prodigal Sons of Psychoanalysis? Universiteit Gent.

- ↑ Williams, David: "Cain and Beowulf: A Study in Secular Allegory, page 21. University of Toronto Press, 1982

- ↑ Whittemore, Amie. "Ishmael - Part 9: Sections 9-11". Cliffs Notes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7204-8021-4.

- ↑ Hamlin, Hannibal (2013-08-29). The Bible in Shakespeare. p. 154. ISBN 9780199677610.

- ↑ Nares, Robert (1859). "A glossary; or collection of words, phrases, names and allusions to customs, proverbs, etc., which have been thought to require illustration in the works of English authors, particularly of Shakespeare, and his contemporaries: By Robert Nares. I". John Russell Smith. Retrieved 2 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Frey, John Andrew (24 July 1999). A Victor Hugo Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 70. ISBN 9780313298967 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Pop Culture 101: East of Eden". TCM.com. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ↑ Hughes, William (21 December 2015). The Encyclopedia of the Gothic, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119064602. Retrieved 2 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jolyon P.; Marriage, Sophia (1 June 2003). Mediating Religion: Studies in Media, Religion, and Culture. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567088079. Retrieved 2 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Melton, J. Gordon (1 September 2010). "The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead". Visible Ink Press. p. 274. Retrieved 7 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Van Scott, Miriam (1999). The Encyclopedia of Hell. Macmillan. p. 74. ISBN 9780312244422.

- ↑ Prudom, Laura (15 April 2015). "'Supernatural': Misha Collins Teases 'Enormous Sacrifices' Ahead of Season Finale". Variety. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ Rockett, Darcel (11 July 2017). "'Supernatural' spinoffs we'd love to see". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "jp.dk - Bibelen (Nørrebro Teater)". 5 October 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ Adam White (September 23, 2017). "Mother! explained". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ↑ Mitovich, Matt Webb. "Lucifer's Tom Ellis: Sinnerman Story Twist 'Opens Up a Nice Can of Worms,' Tees Up a 'Strange Bromance'". TV Line. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

Bibliography

- Alter, Robert (2008). The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. W. W. Norton & Compan. ISBN 9780393070248.

- BDB, Francis Brown; Samuel Rolles Driver; Charles Augustus Briggs (1997) [1906]. The Brown Driver Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon: with an appendix containing the biblical Aramaic; coded with the numbering system from "Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible" (7. print. ed.). Peabody: Hendrickson. ISBN 978-1565632066.

- Byron, John (2011). Cain and Abel in Text and Tradition: Jewish and Christian Interpretations of the First Sibling Rivalry. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004192522.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1-11. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-37287-1.

- Doukhan, Abi (2016). Biblical Portraits of Exile: A Philosophical Reading. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-7241-0

- Gmirkin, Russell E. (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567134394.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). An Introduction to the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-1047-7

- Kugel, James L. (1998). Traditions of the Bible: A Guide to the Bible as it was at the Start of the Common Era. Cambridge, Massachusetts [u.a.]: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674791510.

- Luttikhuizen, Gerard P. (Editor) (2003). Eve's Children: The Biblical Stories Retold and Interpreted in Jewish and Christian traditions (Vol. 5 ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004126152.

- Sailhamer, John H. (2010). The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830878888.

Further reading

- Aptowitzer, Victor (1922). Kain und Abel in der agada: den Apokryphen, der hellenistischen, christlichen und muhammedanischen literatur (Vol. 1 ed.). R. Löwit.

- Glenthøj, Johannes Bartholdy (1997). Cain and Abel in Syriac and Greek writers: (4th - 6th centuries). Lovanii: Peeters. ISBN 978-9068319095.

External links

- Bible (King James) / Genesis 4

- Book of Moses, Chapter 5 in Pearl of Great Price

- Cain

- Abel

- Genesis 4 (KJV) at BibleGateway.com

- Story of Cain and Abel in Sura The Table (Al Ma'ida)

- Parallel voweled Hebrew and English (JPS 1917)

- Rashi on Genesis, Chapter 4, by Rashi

- Sanhedrin 37