Four temperaments

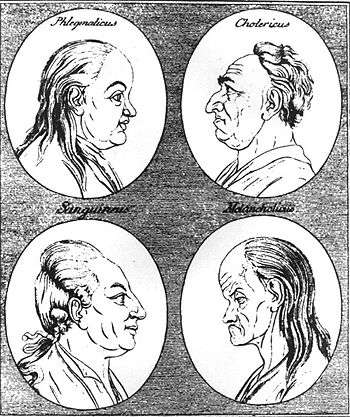

Phlegmatic and choleric (above)

Sanguine and melancholic (below)

The Four temperament theory is a proto-psychological theory that suggests that there are four fundamental personality types: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic.[2][3] Most formulations include the possibility of mixtures between the types where an individual's personality types overlap and they share two or more temperaments.

The Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) described the four temperaments as part of the ancient medical concept of humorism, that four bodily fluids affect human personality traits and behaviors. Though modern medical science does not define a fixed relationship between internal secretions and personality, some psychological personality type systems use categories similar to the Greek temperaments.

History and development

Temperament theory has its roots in the ancient four humors theory. It may have origins in ancient Egypt[4] or Mesopotamia,[5] but it was the Greek physician Hippocrates (460–370 BC) who developed it into a medical theory. He believed certain human moods, emotions and behaviors were caused by an excess or lack of body fluids (called "humors"): blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm.[3] Next, Galen (AD 129 – c. 200) developed the first typology of temperament in his dissertation De temperamentis, and searched for physiological reasons for different behaviors in humans. He classified them as hot/cold and dry/wet taken from the four elements.[6] There could also be "balance" between the qualities, yielding a total of nine temperaments. The word "temperament" itself comes from Latin "temperare", "to mix". In the ideal personality, the complementary characteristics of warm-cool and dry-moist were exquisitely balanced. In four less ideal types, one of the four qualities was dominant over all the others. In the remaining four types, one pair of qualities dominated the complementary pair; for example, warm and moist dominated cool and dry. These latter four were the temperamental categories Galen named "sanguine", "choleric", "melancholic" and "phlegmatic" after the bodily humors, respectively. Each was the result of an excess of one of the humors that produced, in turn, the imbalance in paired qualities.[3][7][8][9]

In his Canon of Medicine (a standard medical text at many medieval universities), Persian polymath Avicenna (980–1037 AD) extended the theory of temperaments to encompass "emotional aspects, mental capacity, moral attitudes, self-awareness, movements and dreams."[10]

Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654), described the humours as acting as governing principles in bodily health, with astrological correspondences,[11] and explained their influence upon physiognomy and personality.[12] Culpeper proposed that, while some people had a single temperament, others had an admixture of two, a primary and secondary temperament.[13] Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), Alfred Adler (1879–1937), Erich Adickes (1866–1925), Eduard Spranger (1914), Ernst Kretschmer (1920), and Erich Fromm (1947) all theorized on the four temperaments (with different names) and greatly shaped our modern theories of temperament. Hans Eysenck (1916–1997) was one of the first psychologists to analyze personality differences using a psycho-statistical method (factor analysis), and his research led him to believe that temperament is biologically based. The factors he proposed in his book Dimensions of Personality were neuroticism (N), the tendency to experience negative emotions, and extraversion (E), the tendency to enjoy positive events, especially social ones. By pairing the two dimensions, Eysenck noted how the results were similar to the four ancient temperaments.

Other researchers developed similar systems, many of which did not use the ancient temperament names, and several paired extraversion with a different factor, which would determine relationship/task-orientation. Examples are DiSC assessment, social styles, and a theory that adds a fifth temperament. One of the most popular today is the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, whose four temperaments were based largely on the Greek gods Apollo, Dionysus, Epimetheus and Prometheus, and were mapped to the 16 types of the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). They were renamed as Artisan (SP), Guardian (SJ), Idealist (NF), and Rational (NT). Rather than using extraversion and introversion (E/I) and task/people focus, like other theories, KTS mapped the temperaments to "Sensing" and "Intuition" (S/N, renamed "concrete" and "abstract") with a new pair category, "cooperative" and "pragmatic". When "Role-Informative" and "Role-Directive" (corresponding to orientation to people or to task), and finally E/I are factored in, the 16 types are attained. Finally, the Interaction Styles of Linda V. Berens combines Directing and Informing with E/I to form another group of "styles" which greatly resemble the ancient temperaments, and these are mapped together with the Keirsey Temperaments onto the 16 types.

Modern medical science has rejected the theories of the four temperaments, though their use persists as a metaphor within certain psychological fields.[14]

| Classical | Element | Adler[15] |

|---|---|---|

| Melancholic | Earth | Avoiding |

| Phlegmatic | Water | Getting |

| Sanguine | Air | Socially useful |

| Choleric | Fire | Ruling |

Four fundamental personality types

Most individuals tend to have aspects of their personality that identify with each of the four temperaments. However, there are usually two primary temperaments that are displayed at a significantly higher level. An individual could be any combination of the following four temperaments:

Sanguine

The personality type of Sanguine is described primarily as being enthusiastic, active, and social. Sanguines tend to be more extroverted and enjoy being part of a crowd; they find that being social, outgoing, and charismatic is easy to accomplish.[2][3] Individuals with this personality have a hard time doing nothing and engage in more risk seeking behaviour.[2]

Choleric

Choleric individuals also tend to be more extroverted. They are described as being independent, decisive, and goal oriented. They enjoy being in charge of a group since they have many leadership qualities as well as ambition. Choleric personalities also have a logical and fact-based outlook on the world.

Melancholic

These individuals tend to be analytical, detail oriented, and are deep thinkers and feelers. They are introverted and try to avoid being singled out in a crowd.[2] A melancholic personality leads to self-reliant individuals, who are thoughtful, reserved, and often anxious.[2] They often strive for perfection within themselves and their surroundings, which leads to tidy and detail oriented behaviour.[2]

Phlegmatic

A phlegmatic individual tends to be relaxed, peaceful, quiet, and easy-going.[2] They are sympathetic and care about others, yet try to hide their emotions. Phlegmatic individuals also are good at generalizing ideas or problems to the world and making compromises.[2]

Decline in popularity

When the concept of the temperaments was on the wane, many critics dropped the phlegmatic, or defined it purely negatively, such as the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, as the absence of temperament. In the five temperaments theory, the classical phlegmatic temperament is in fact deemed to be a neutral temperament, whereas the "relationship-oriented introvert" position traditionally held by the phlegmatic is declared to be a new "fifth temperament".

Contemporary writings

In Waldorf education and anthroposophy, the temperaments are believed to help understand personality.

Christian writer Tim LaHaye has attempted to repopularize the ancient temperaments through his books.[16][17][18]

Writer Florence Littauer describes the four personality types in her book Personality Plus.

Cultural references

At the end of the 18th-century, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach composed the trio sonata in c minor „Sanguineus et Melancholicus“ Wq 161/1.

In 1946 George Balanchine choreographed a ballet he titled The Four Temperaments, set to music he commissioned from Paul Hindemith. The music, and thus the ballet, is in five parts: a theme and four variations titled Melancholic, Sanguine, Phlegmatic, and Choleric.

Émile Zola consciously employed the four temperaments in Thérèse Raquin.[19]

Carl Nielsen's Symphony No. 2 (Op.16), composed 1901–02, is titled and structured upon "The Four Temperaments."[20]

In the Warhammer 40,000 series of games and novels, the protagonist, Horus Lupercal, maintains an inner circle of 4 advisors known as “The Mournival”, chosen as exemplars of the Four Temperaments, which combine to create a “balance of the humours.”[21]

See also

References

- ↑ Woodcut from Johann Kaspar Lavater, Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe (1775–1778)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 http://www.thetransformedsoul.com/additional-studies/miscellaneous-studies/the-four-human-temperaments

- 1 2 3 4 Merenda, P. F. (1987). "Toward a Four-Factor Theory of Temperament and/or Personality". Journal of Personality Assessment. 51: 367–374.

- ↑ van Sertima, Ivan (1992). The Golden Age of the Moor. Transaction Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 1-56000-581-5.

- ↑ Sudhoff, Karl (1926). "Essays in the History of Medicine". Medical Life Press, New York: 67, 87, 104.

- ↑ Boeree, C. George. "Early Medicine and Physiology". Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ Kagan, Jerome (1998). Galen's Prophecy: Temperament In Human Nature. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-08405-2.

- ↑ Osborn L. Ac., David K. "INHERENT TEMPERAMENT". Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Lutz, Peter L. (2002). The Rise of Experimental Biology: An Illustrated History. Humana Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-89603-835-1.

- ↑ Nicholas Culpeper (1653) An Astrologo-Physical Discourse of the Human Virtues in the Body of Man, transcribed and annotated by Deborah Houlding. Skyscript, 2009 (retrieved 16 November 2011). Originally published in Culpeper's Complete Herbal (English Physician). London: Peter Cole, 1652.

- ↑ Nicholas Culpeper, Semeiotica Urania, or Astrological Judgement of Diseases. London: 1655. Reprint, Nottingham: Ascella, 1994.

- ↑ Greenbaum, Dorian Gieseler (2005). Temperament: Astrology's Forgotten Key. Wessex Astrologer. pp. 42, 91. ISBN 1-902405-17-X.

- ↑ Martindale, Anne E.; Martindale, Colin (1988). "Metaphorical equivalence of elements and temperaments: Empirical studies of Bachelard's theory of imagination". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 55 (5): 836. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.5.836.

- ↑ Lundin, Robert W. (1989). Alfred-Adler's Basic Concepts and Implications. Taylor and Francis. p. 54. ISBN 0-915202-83-2.

- ↑ LaHaye, Tim (1966). The Spirit Controlled Temperament. Tyndale Publishing.

- ↑ LaHaye, Tim (1984). Your Temperament: Discover Its Potential. Tyndale Publishing. ISBN 0-8423-6220-7.

- ↑ LaHaye, Tim. Why You Act the Way You Do. Tyndale Publishing. ISBN 0-8423-8212-7.

- ↑ Zola, Preface to Thérèse Raquin.

- ↑ Foltmann, Niels Bo, ed. (1998). Symphony No. 2 (PDF). Carl Nielsen Works. II. Instrumental Music. 2. The Carl Nielsen Edition, Royal Danish Library. ISBN 978-87-598-0913-6. ISMN M-66134-000-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2014.

- ↑ ”Horus Rising” (Novel), by Dan Abnett

Further reading

- Arikha, Noga (2007). Passions and Tempers: A History of the Humours. Harpers. ISBN 978-0060731175

External links

- In Our Time (BBC Radio 4) episode on the four humours in MP3 format, 45 minutes