29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann

The comet Schwassmann–Wachmann 1 (Spitzer infrared image in false colours) Nasa | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Arno Arthur Wachmann |

| Discovery date | November 15, 1927 |

| Alternative designations |

1908 IV; 1927 II; 1941 VI; 1957 IV; 1974 II; 1989 XV; |

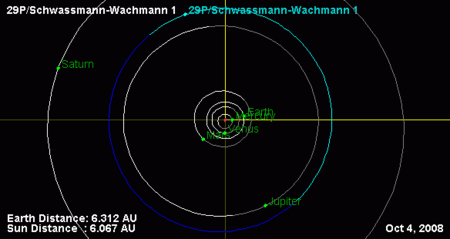

| Orbital characteristics A | |

| Epoch | March 6, 2006 |

| Aphelion | 6.25 AU |

| Perihelion | 5.722 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 5.986 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.0441 |

| Orbital period | 14.65 a |

| Inclination | 9.3903° |

| Dimensions | 30.8 km[1] |

| Last perihelion | July 10, 2004[2] |

| Next perihelion | March 7, 2019[3][4] |

Comet 29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann, also known as Schwassmann–Wachmann 1, was discovered on November 15, 1927, by Arnold Schwassmann and Arno Arthur Wachmann at the Hamburg Observatory in Bergedorf, Germany.[5] It was discovered photographically, when the comet was in outburst and the magnitude was about 13.[5] Precovery images of the comet from March 4, 1902, were found in 1931 and showed the comet at 12th magnitude.[5]

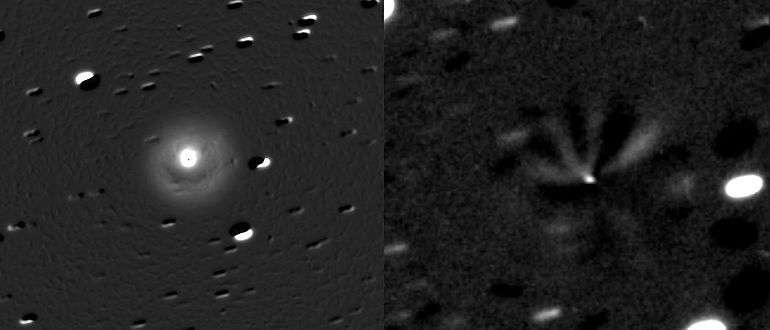

The comet is unusual in that while normally hovering at around 16th magnitude, it suddenly undergoes an outburst. This causes the comet to brighten by 1 to 4 magnitudes.[6] This happens with a frequency of 7.3 outbursts per year,[6] fading within a week or two. The magnitude of the comet has been known to vary from 19th magnitude to 9th magnitude, a ten thousand-fold increase in brightness, during its brightest outbursts. Highly changing surface processes are suspected to be responsible for the observed behavior.[6]

The comet is thought to be a member of a relatively new class of objects called "centaurs", of which at least 400 are known.[7] These are small icy bodies with orbits between those of Jupiter and Neptune. Astronomers believe that centaurs are recent escapees from the Kuiper belt, a zone of small bodies orbiting in a cloud at the distant reaches of the Solar System. Frequent perturbations by Jupiter[1] will likely accumulate and cause the comet to migrate either inward or outward by the year 4000.[8]

The dust and gas comprising the comet's nucleus is part of the same primordial materials from which the Sun and planets were formed billions of years ago. The complex carbon-rich molecules they contain may have provided some of the raw materials from which life originated on Earth.

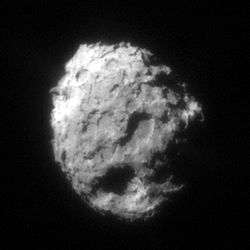

The comet nucleus is estimated to be 30.8 kilometers in diameter.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 "JPL Close-Approach Data: 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1" (last observation: April 10, 2009). Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ 29P past, present and future orbital elements

- ↑ Syuichi Nakano (January 29, 2012). "29P/Schwassmann-Wachman 1 (NK 2189)". OAA Computing and Minor Planet Sections. Retrieved 2012-02-18.

- ↑ Patrick Rocher (February 4, 2012). "Note number : 0015 P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 : 29P". Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides. Retrieved 2012-02-18.

- 1 2 3 Kronk, Gary W. (2001–2005). "29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1". Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-13. (Cometography Home Page)

- 1 2 3 Trigo-Rodríguez; Melendo; García-Hernández; Davidsson; Sánchez (2008). "A continuous follow-up of Centaurs, and dormant comets: looking for cometary activity" (PDF). European Planetary Science Congress. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ "JPL Small-Body Database Search". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ "Twelve clones of 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann diverging by the year 4000". Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved 2009-04-30. (Solex 10) Archived April 29, 2009, at WebCite

- ↑ Trigo-Rodriguez et al., Outburst activity in comets, I. Continuous monitoring of comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1

- ↑ Trigo-Rodriguez et al., Outburst activity in comets , II. A multi-band photometric monitoring of comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1

External links

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris

- 29P at CometBase

- 29P at Las Cumbres Observatory (8 Feb 2010 12:23, 60 seconds)

- 29P (Joseph Brimacombe April 18, 2013)

| Numbered comets | ||

|---|---|---|

| Previous 28P/Neujmin |

29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann | Next 30P/Reinmuth |