2013–present economic crisis in Venezuela

The Venezuelan economic crisis also known as Great Depression in Venezuela[1], refers to the deterioration that began to be noticed in the main macroeconomic indicators from the year 2012, and whose consequences have extended in time to the present, not only economically but also politically and socially.

Origins

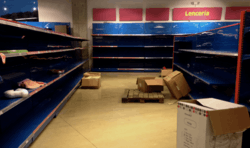

According to the misery index in 2013, Venezuela ranked as the top spot globally with the highest misery index score.[2][3] The International Finance Corporation ranked Venezuela one of the lowest countries for doing business with, ranking it 180 of 185 countries for its Doing Business 2013 report with protecting investors and taxes being its worst rankings.[4][5] In early 2013, the bolívar fuerte was devalued due to growing shortages in Venezuela.[6] The shortages included necessities such as toilet paper, milk and flour.[7] Shortages also affected healthcare in Venezuela, with the University of Caracas Medical Hospital ceasing to perform surgeries due to the lack of supplies in 2014.[8] The Bolivarian government's policies also made it difficult to import drugs and other medical supplies.[9] Due to such complications, many Venezuelans died avoidable deaths with medical professionals having to use limited resources using methods that were replaced decades ago.[10][11]

In 2014, Venezuela entered an economic recession having its GDP growth decline to -3.0%.[12] Venezuela was placed at the top of the misery index for the second year in a row.[13] The Economist said Venezuela was "[p]robably the world’s worst-managed economy".[14] Citibank believed that "the economy has little prospect of improvement" and that the state of the Venezuelan economy was a "disaster".[15] The Doing Business 2014 report by the International Finance Corporation and the World Bank ranked Venezuela one score lower than the previous year, then 181 out of 185.[16] The Heritage Foundation ranked Venezuela 175th out of 178 countries in economic freedom for 2014, classifying it as a "repressed" economy according to the principles the foundation advocates.[17][18] According to Foreign Policy, Venezuela was ranked last in the world on its Base Yield Index due to low returns that investors receive when investing in Venezuela.[19] In a 2014 report titled Scariest Places on the Business Frontiers by Zurich Financial Services and reported by Bloomberg, Venezuela was ranked as the riskiest emerging market in the world.[20] Many companies such as Toyota, Ford Motor Co., General Motors Company, Air Canada, Air Europa, American Airlines, Copa Airlines, TAME, TAP Airlines and United Airlines slowed or stopped operation due to the lack of hard currency in the country,[21][22][23][24][25] with Venezuela owing such foreign companies billions of dollars.[26] Venezuela also dismantled CADIVI, a government body in charge of currency exchange. CADIVI was known for holding money from the private sector and was suspected to be corrupt.[27]

Venezuela again topped the misery index according to the World Bank in 2015.[28][29] The IMF predicted in October 2015 an inflation rate of 159% for the year 2015—the highest rate in Venezuelan history and the highest rate in the world—and that the economy would contract by 10%.[30][31] According to leaked documents from the Central Bank of Venezuela, the country ended 2015 with an inflation rate of 270% and a shortage rate of goods over 70%.[32][33]

President Nicolás Maduro reorganized his economic cabinet in 2016 with the group mainly consisting of leftist Venezuelan academics.[34] According to Bank of America's investment division Merrill Lynch, Maduro's new cabinet was expected to tighten currency and price controls in the country.[34] Alejandro Werner, the head of IMF's Latin American Department, stated that 2015 figures released by the Central Bank of Venezuela were not accurate and that Venezuela's inflation for 2015 was 275%. Other forecast inflation figures by IMF and Bank of America were 720%[35][36] and 1,000% in 2016,[37][38] Analysts believed that the Venezuelan government has been manipulating economic statistics, especially since they did not report adequate data since late 2014.[37] According to economist Steve Hanke of Johns Hopkins University, the Central Bank of Venezuela delayed the release of statistics and lied about figures much like the Soviet Union did, with Hanke saying that a lie coefficient had to be used to observe Venezuela's economic data.[39]

By 2016, media outlets said that Venezuela was suffering an economic collapse[40][41] with the IMF estimating a 500% inflation rate and 10% contraction in the GDP.[42] In December 2016, monthly inflation exceeded 50 percent for the 30th consecutive day, meaning the Venezuelan economy was officially experiencing hyperinflation, making it the 57th country to be added to the Hanke-Krus World Hyperinflation Table.[43]

On 25 August 2017, it was reported that new United States sanctions against Venezuela did not ban trading of the country’s existing non-government bonds, with the sanctions instead including restrictions intended to block the government’s ability to fund itself.[44]

On 26 January 2018, the government ended the protected, subsidized fixed exchange rate mechanism that was highly overvalued as a result of rampant inflation.[45] The National Assembly (led by the opposition) said inflation in 2017 was over 4,000%, a level other independent economists also agreed with.[46] In February, the government launched an oil backed cryptocurrency called the petro.[47]

Bloomberg's Cafe Con Leche Index calculated the price increase for a cup of coffee to have increased by 718% in the 12 weeks before 18 January 2018, an annualized inflation rate of 448,000%.[48] The finance commission of the National Assembly noted in July 2018 that prices were doubling every 28 days with an annualized inflation rate of 25,000%.[49]

The country was heading for a selective default in 2017.[50] In early 2018, the country was in default, meaning it could not pay its lenders.[51]

Prices

Due to the lack of own resources, Venezuela has traditionally exported all its oil abroad, so the energy crisis of 2014 produced a strong inflationary trend. In June 2013, accumulated inflation in the last twelve months was 56.2%. The sharp drop between 2014 and 2016 in the price of oil, made us fear a risk of hyperinflation, Venezuela reached in 2015 the highest inflation rate in the last 35 years, and in March 2016 there was hyperinflation for the first time since recorded data In October 2016, the economy continued to contract while inflation increased again. Between 2017 and 2018, prices rose 2616% 18, this increase combined with austerity measures and high unemployment negatively impacted the living standards of Venezuelans. At the same time the average wages decreased (real) and the purchasing power was significantly reduced.

Employment crisis

After having completed substantial improvements over the second half of the 1990s and during the 2000s, which put a few regions on the brink of full employment, Venezuela suffered a severe setback in 2015, when it saw its unemployment rate surging to 1994 levels.

Venezuelan's unemployment rate hit 17.4% at the end of June 2017, with the jobless total now having doubled over the past 12 months, when two million people lost their jobs.[52]

Public debt

Public debt, which in 2010 represented 34.62% of GDP, doubled in three years, standing at 52.1% in 2013, reaching 52.98% of Gross Domestic Product in 2016.[53] Instead, the risk premium began to skyrocket at the end of 2014 to a record high of 3,181 points, increasing fears of a possible IMF bailout of Venezuela. The risk premium set a record in August 2017, recording 5,000 basic points exceeding eight times Greece's risk premium.[54]

Ratings

In the beginning of the crisis, Venezuela's credit ratings were downgraded to "junk territory" or below investment grade with negative outlooks according to most rating agencies.[55][56][57] In a little more than one year, Standard and Poor's downgraded Venezuela's credit rating three times; from B+ to B in June 2013,[58] B to B- in December 2013[55] and from B- to CCC+ in September 2014.[56] Fitch Ratings also lowered each of Venezuela's credit ratings in March 2014 from B+ to B[59] and even lower from B to CCC in December 2014.[60] In December 2013, Moody's Investors Service also downgraded both Venezuela's local (B1) and foreign currency (B2) ratings to Caa1.[57] The noted reasons of credit rating changes were the greatly increased likelihood of economic and financial collapse due to the Venezuelan government's policies and an "out of control" inflation rate.[56][57][59]

In July 2017, Standard & Poor's lowered both the domestic and foreign credit ratings of Venezuela to CCC- due to the increasing risk of default.[61] Fitch Ratings followed suit in August 2017, lowering local and foreign credit ratings to CC.[62] In November 2017 Standard & Poor's rated Venezuela in technical default and Fitch ratings rated Venezuela's oil company PDVSA in restrictive default - one rank above full default.

See also

References

- ↑ "La crisis venezolana ya tiene nombre: Gran depresión económica". 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Hanke, John H. "Measuring Misery around the World". The CATO Institute. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Steve H. Hanke". Cato Institute. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ease of Doing Business in Venezuela, RB". Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "DOING BUSINESS 2013" (PDF). Report. International Finance Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Slashes Currency Value". Wall Street Journal. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Lopez, Virginia (26 September 2013). "Venezuela food shortages: 'No one can explain why a rich country has no food'". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Médicos del Hospital Universitario de Caracas suspenden cirugías por falta de insumos". Globovision. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "Latin America's weakest economies are reaching breaking-point". Economist. 1 February 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's medical crisis requires world's attention". The Boston Globe. 28 April 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ "Doctors say Venezuela's health care in collapse". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Country and region specific forecasts and data". World Bank. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Amid Rationing, Venezuela Takes The Misery Crown". Investors Business Daily. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's economy Of oil and coconut water Probably the world's worst-managed economy". The Economist. 20 September 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ↑ "Citi considera que la economía venezolana es un "desastre"". El Universal. 3 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Doing Business 2014" (PDF). The World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "The Heritage Foundation". About Heritage. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ "Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ↑ Yapur, Nicolle (30 June 2014). "Políticas económicas en Venezuela ahuyentan el capital extranjero". El Nacional. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "Scariest Places on the Business Frontiers". Bloomberg. 2 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ Hagiwara, Yuki (7 February 2014). "Toyota Halts Venezuela Production as Car Sales Fall". Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Ford Cutting Production in Venezuela on Growing Dollar Shortage". Businessweek. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ Deniz, Roberto (7 February 2014). "General Motors sees no resolution to operations in Venezuela". El Universal. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Mogollon, Mery (24 January 2014). "Venezuela sees more airlines suspend ticket sales, demand payment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (24 January 2014). "Airlines keep cutting off Venezuelans from tickets". USA Today. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (10 January 2014). "Venezuelans blocked from buying flights out". USA Today. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Shuffles Economic Team". The Wall Street Journal. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Anderson, Elizabeth (3 March 2015). "Which are the 15 most miserable countries in the world?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Saraiva, A Catarina; Jamrisko, Michelle; Fonseca Tartar, Andre (2 March 2015). "The 15 Most Miserable Economies in the World". Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Cristóbal Nagel, Juan (13 July 2015). "Looking Into the Black Box of Venezuela's Economy". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Gallas, Daniel (7 December 2015). "Venezuela: Economy on the brink?". BBC News Latin America. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ Lopez, Virginia (8 January 2016). "Venezuela's economic crisis worsens as oil prices fall". www.aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ↑ Lozano, Daniel (8 January 2015). "Ni un paso atrás: Maduro insiste con su receta económica". www.lanacion.com.ar. La Nación. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Bank Of America prevé más controles para la economía de Venezuela". El Nacional. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ "IMF: Venezuela Inflation to Surpass 700 Percent". The New York Times. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ↑ "FMI: Inflación de Venezuela en 2016 será de 500%". El Nacional. 17 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Leff, Alex (26 January 2016). "What's it like under 1,000 percent inflation? Venezuela is about to find out". Public Radio International. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. April 2016. ISBN 978-1-47554-372-8. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Hanke, Steve H. (15 January 2016). "Venezuela's Lying Statistics". Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Hungry Venezuelans Flee in Boats to Escape Economic Collapse". The New York Times. 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuelans face collapsing economy, starvation and crime".

- ↑ "Why you need sackfuls of banknotes to shop in Venezuela". BBC News. 2016-12-18. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ Jim Wyss (12 December 2016). "Entering a 'world of economic chaos,' Venezuela struggles with hyperinflation". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ Cui, Carolyn (August 25, 2017), Venezuelan Bonds Up After New U.S. Sanctions Spare Debt Trading

- ↑ "Venezuela eliminates heavily subsidized DIPRO forex rate". Reuters. 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ Sequera, Vivian (18 February 2018). "Venezuelans report big weight losses in 2017 as hunger hits". Reuters. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ Krygier, Rachelle (20 February 2018). "Venezuela launches the 'petro,' its cryptocurrency". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Venezuelan Hyperinflation Explodes, Soaring Over 440,000 Percent". Bloomberg. 18 January 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ Caracas, Stephen Gibbs (12 June 2018). "Venezuela suffering 25,000% inflation". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 23 July 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Russia extends lifeline as Venezuela struggles with 'selective default'".

- ↑ "Venezuela oil assets seizure by Conoco may start wave".

- ↑ "Central obrera cifra en 18,5% la tasa de desempleo en Venezuela". EntornoInteligente. 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Venezuela - Public debt (% of GDP) - 2016". en.actualitix.com.

- ↑ elEconomista.es. "Venezuela dispara su riesgo de impago: es ocho veces superior al de Grecia - elEconomista.es".

- 1 2 "S&P cuts Venezuela credit rating to B-minus". Al Jazeera. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 Dulaney, Chelsey; Vyas, Kejal (16 September 2014). "S&P Downgrades Venezuela on Worsening Economy Rising Inflation, Economic Pressures Prompt Rating Cut". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Moody's downgrades Venezuela to Caa1; outlook negative". Moody's Investors Service. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ Bases, Daniel (17 June 2013). "Update 2 – S&P downgrades Venezuela's sovereign credit rating to B". Reuters. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Fitch Downgrades Venezuela to 'B'; Outlook Negative". Reuters. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Fitch Downgrades Venezuela's IDRs to 'CCC'". Reuters. 18 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Cut Deeper Into Junk by S&P". Bloomberg.com. 11 July 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ DeFotis, Dimitra (30 August 2017). "Venezuela Bond Default 'Probable' Fitch Downgrade Says". Barron's. Retrieved 31 August 2017.