2011 United Nations Bombardier CRJ-100 crash

4L-GAE seen at Odessa International Airport in May 2008 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 4 April 2011 |

| Summary | Microburst-induced windshear |

| Site |

N'djili Airport, Democratic Republic of the Congo 4°19′S 15°18′E / 4.317°S 15.300°ECoordinates: 4°19′S 15°18′E / 4.317°S 15.300°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Bombardier CRJ-100ER |

| Operator | Georgian Airways for the United Nations[1] |

| Registration | 4L-GAE |

| Flight origin | Goma International Airport, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Stopover | Bangoka International Airport, Kisangani, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Destination | N'djili, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Passengers | 29 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 32 |

| Injuries | 1 (serious) |

| Survivors | 1 |

On 4 April 2011, a Georgian Airways Canadair Regional Jet (CRJ 100 ER), registration 4L-GAE, using call sign "UNO 834", operating a domestic flight from Kisangani to Kinshasa for United Nation's Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo, crashed during Go Around at Kinshasa Airport, at 12:56:52 UTC. At the time of the accident, Kinshasa airfield was experiencing a severe thunderstorm.

The aircraft impacted the ground 170 meters (560 ft) to the left and abeam the displaced threshold of Runway 24in about a 10 degrees nose down attitude. At the time of impact, aircraft‟s heading was 220 degrees and its speed was 180 knots (330 km/h; 210 mph). Following the impact, the aircraft skipped, started breaking up, skidded along the ground and rolled inverted before coming to a halt. During this process, parts of the aircraft including undercarriage, engines, wings and tail section sheared off.[2][3] There were 32 fatalities, with the sole survivor a Congolese journalist.[2][4]

Aircraft

The aircraft was a Bombardier CRJ-100ER, registered 4L-GAE,[3] c/n 7070. The aircraft was delivered in 1996 to French airline Brit Air, as F-GRJA. It was sold to Georgian Airways in September 2007.[5] Leased from Georgian Airways,[3] it was operated by the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO)[2] using the callsign UN-834.

Accident

On Monday, 4 April 2011, a Georgian Airways CRJ-100ER, registration 4L-GAE, chartered by MONUSCO was planned to carry out a flight on route Kinshasa - Kisangani- Kinshasa, using call sign UNO 834. At Kisangani, 29 passengers boarded the aircraft for the flight to Kinshasa; 594 kg of luggage was loaded for this sector. Besides the Captain and the Co-Pilot, the crew consisted of a Flight Attendant and a Ground Engineer. Pilot in Command (PIC) was the Pilot Flying (PF) while the Co-Pilot was the Pilot Not flying (PNF) for this sector. The aircraft took off from Kisangani for Kinshasa at 11:18 and climbed to Flight Level 300. At 12:39, UNO 834 requested for descent and was cleared to descend to flight level 100. Meanwhile, on the on-board weather radar, the crew were able to notice presence of severe weather around and over Kinshasa airfield. At 12:49, the crew again sought latest weather information from Kinshasa ATC. They were informed that Kinshasa was reporting wind 210 degrees with 8 knots, visibility 8 km, and thunderstorm over the station. The aircraft later cleared to land in the airport.

The aircraft crashed upon landing on N'djili Airport's Runway 24,[6] shortly before 14:00 local time (13:00 UTC).[7] The aircraft was on a domestic flight from Goma to Ndjili via Kisangani.[8] Heavy rain was falling at the time.[9] The METAR in force at the time showed thunder showers and rain.[6][Note A] According to a United Nations official, the plane "landed heavily, broke into two and caught fire".[9] An eyewitness suggested windshear as a cause.[6] The Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations Alain Le Roy indicated that the poor weather was a key element in the cause of the crash.[10] The main part of the fuselage came to a rest inverted and in a badly damaged condition. The severe nature of the accident caused massive external and internal injuries to the occupants. ECR teams brought out the crew and the passengers from the wreckage. Most of them were already dead, while a few were badly injured but alive. Nine injured survivors were rushed to a local hospital, some of them died on the way to the hospital. Among those who reached the hospital alive, all but one succumbed to their injuries. Of the four Georgian crew and 29 passengers, there was only one survivor,[2] Francis Mwamba, a Congolese journalist.[11] The survivor was seriously injured.[6] The aircraft manifest listed 20 UN workers.[2] The passengers included UN peacekeepers and officials, humanitarian workers and electoral assistants.[9] Five non-UN passengers were staff from non-governmental organisations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or from other international organisations.[12]

The UN Security Council and the United States have offered their condolences for the accident.[13][14][15] UN flights are frequent in Congo, more than hundreds a week, as they are one of the best available means of transportation in the country; the flying route is one of the most used in the country.[9]

Investigation

MONUSCO set up a task force, which opened an investigation into the accident.[12]

Weather analysis

Investigators retrieved the meteorological data based on basic instruments, and stated that no laser equipment is available to measure cloud base. Similarly, visibility is measured using landmarks rather than a Transmissometer. Kinshasa airport meteorological service is not equipped with weather radar thus cannot accurately forecast and determine approach of dangerous weather phenomenon. To augment meteorological information available to its crew members, MONUSCO had tasked a Contractor- PAE Limited, to provide Meteorological Services including Forecasting and Observation Services, at several airfields in D R Congo. The contractor (PAE Limited) provided these services at Kinshasa as also at Kisangani. However, PAE weather stations were also not equipped with weather radar.[16]

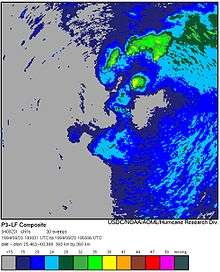

Investigators later retrieved the satellite imagery data from EUMETSAT. The data showed that a huge, cloud mass with very low cloud base, transited through Kinshasa Terminal Area from North East Direction, affected Kinshasa Airfield, before moving away in South West direction. Kinshasa meteorological observers, not being equipped with weather radar, were not aware of the approach of this severe weather system. On the day of the accident, before departing from Kinshasa, the crew were given a thorough meteorological briefing by the PAE provided service. After completing the Kinshasa – Kisangani sector, the crew were provided another weather update, including being provided latest satellite imagery of the weather en route to Kinshasa. Repeated discussion among the crew members regarding "Magenta‟ being shown at and around Kinshasa airfield on their onboard weather radar as evident on the CVR transcript.

Minimum infrastructure

The severe weather phenomenon that affected Kinshasa and its surrounding areas at the time of the accident was a fast moving and severe "Squall Line". The Approach path and Kinshasa airfield were probably covered by inclement weather at the time of the accident. The fast movement of the "Squall Line" can also be visualized by the fact that the weather information provided to the crew at 12:49 by Kinshasa ATC stated 8,000 meters (26,000 ft) of visibility while the weather report (SPECI) at 13:00 reported a visibility of only 500 meters (1,600 ft). The accident occurred at 12:56 So, during the interim period of ten minutes, a rapid change in weather had taken place but the same was not conveyed to the crew by the ATC. The ATC did report a significant change in surface winds to the crew at 12:55 when it reported that surface winds had become 280 degrees, 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph). The crew merely acknowledged this by saying "copied, copied‟ and probably did not correlate this significant change in surface winds with the state of the storm over the airfield.[16]

Information gathered during the accident investigation confirmed that Meteorological services in D.R Congo have limitations in observing and forecasting weather. The absence of weather radar seriously affects the capability to detect, track and provide early warning of the approach of fast moving severe weather phenomenon. Lack of weather radar also affected the Meteorological Services provided to MONUSCO by PAE. Despite the lack of weather radar, the approaching "Squall Line" should have been observed when it came within visual range of Meteorological Observers on ground and appropriate warning should have been issued via the ATC to all approaching aircraft. The same was not done.[16]

Flight data recorders

The FDR and CVR were found. The FDR had suffered damage during the accident and direct download of data was not possible. BEA used alternative procedures to download data from the FDR. The data was later transferred electronically to Transportation Safety Board, Canada which took the lead in analysis of data. The FDR was able to provide good information about the sequence of events leading up to the accident. Downloaded Data indicated that all aircraft systems were functioning normally and no technical failures were recorded during the flight.[16]

CVR transcript contains details of extensive discussion among the crew members about the weather en route and over Kinshasa. First indication of Crew's realization of the presence of bad weather en route to Kinshasa was evident at 12:37, when the aircraft was between position GURUT and UDRID, over 100 NMs from Kinshasa. The crew got this indication through their on-board weather radar. At 12:38, the crew again discussed the weather when the Captain said that the (radar) beam was clearly showing the clouds. extended communication among the crew of extreme bad weather being present at and around Kinshasa and the way to avoid it, is heard on the CVR. The co-pilot exclaimed at 12:45 that the weather return being picked up on their radar was very big. Crew also discussed that the clouds were moving, so in next 10 minutes needed to reach the airfield, the clouds would have moved off the airfield. They also seemed to have a doubt whether the returns being picked up on the weather radar were ground echoes or were severe weather (Magenta) indications. The co-pilot confirmed that the returns were not ground echoes but were radar returns (Magenta) from very severe weather.[16]

When approaching about 32 NMs from the airfield, the Captain directed the co-pilot to ask again for latest weather as the ATC had reported 10,000 meters (33,000 ft) visibility earlier while the weather being shown on weather radar seemed much worse. The crew discussed a way to go through / in between / around the weather. The co-pilot was also again heard exclaiming about the huge size of the cell/severe weather, seen on their weather radar. The co-pilot also suggested to wait and orbit for 10 minutes as the cell could be observed to be moving already, but the Captain did not respond to the suggestion. The Captain visually spotted the runway at 12:54. The Over speed Audio warning is audible on the CVR in 12:55 as the flaps were being lowered in excess of permissible speed. At 12:56:21, sound similar to rain falling on the cockpit was picked up on the CVR. Rain falling on the windscreen is audible on the CVR until end of recording.[16]

The Captain ordered a Go Around at 12:56 with a call of "Go Around, Flaps 8‟. At that time, the aircraft was at 218 feet (66 m), with speed of 156 knots (289 km/h; 180 mph). For the Go Around, thrust was opened to about 89–90%; pitch attitude was increased initially to about 8 degrees nose up which came down subsequently to lower pitch values. Landing gear was not selected up.[16]

Flight Data Recorder shows that during the Go Around, when the aircraft was climbing through 397 feet (121 m) with a pitch of 4–5 degrees nose up and at an indicated air speed of 149 knots (276 km/h; 171 mph), there was an external influence on the aircraft at 12:56. This external influence resulted in the aircraft pitch changing to 7 degrees nose down within the next five seconds. Windshear warning came on at 12:56, pitch attitude steepened further to about 9–10 degrees nose down, and the speed increased to 180 knots (330 km/h; 210 mph). As a consequence, the aircraft rapidly lost height.[16]

Impact with the ground seems to have occurred at 12:56. In the very last second before the aircraft impacted the ground, there was an attempt by the crew to pull up the nose of the aircraft, as evidenced by a significant and instantaneous elevator deflection recorded on the FDR.[16]

Possible pilot error

Having noticed the non-standard descent and approach profile flown by the crew in the accident flight, Investigation Team members decided to review the descent and approach profiles flown by the crew during the previous five flights too. Data for the last ten minutes of these five flights was downloaded by TSB and sent to all investigation team members. The data revealed that on two of these previous five flights, crew had carried out non-standard descents as the aircraft's indicated air speed had not been reduced below 250 knots (460 km/h; 290 mph) while descending below 10,000 feet (3,000 m). In one of these flights, the speed was above 250 knots (460 km/h; 290 mph) until as late as 5,100 feet (1,600 m).[16]

On-board weather radar gave good information to the crew about the approach and movement of the severe weather system. The CVR contains details of repeated discussion of weather among the crew between 12:38 and 12:54. Initially, there was some doubt among the crew members whether the radar returns being displayed were ground echoes or were from inclement weather around the airfield. However, the crew soon realized that the weather radar was not showing ground echoes but was indicating adverse weather as confirmed by the co-pilot's exclamatory comments at 12:46 and at 12:47. They even discussed that the clouds were moving and hoped that the airfield would be clear of clouds by the time they reached the airfield.[16]

At 12:54, the co-pilot visually picked up the runway to his right. The co-pilot prompted the PIC to go towards the runway on the right at 12:54:15 saying "runway in sight, nothing there, only radar shows...‟ He repeated "Go to the right, I would say, there is nothing there‟. At 12:54:35, he again said "that is, that is, that is, runway in sight, there is nothing there‟ the co-pilot reiterated "Well, that is, don't you see…‟ It was at this stage that the Captain also saw the runway because immediately thereafter, he disengaged the autopilot to start a turn towards the runway and acknowledged to the co-pilot that he had the runway in sight.[16]

When the Captain disengaged the autopilot to turn towards the runway at 12:54:52, the aircraft was only 6.4 nautical miles (11.9 km; 7.4 mi) from Threshold, in clean configuration, at 3,267 feet (996 m) of altitude and flying at 210 knots (390 km/h; 240 mph). To attempt a landing from this stage of flight, in the presence of extreme weather being indicated on the weather radar, is indicative of inappropriate decision-making in the cockpit and inadequate CRM. While carrying out the high speed and unstabilized Approach, the crew probably faced a situation overload. This may have also affected crew's decision-making capability.[16]

Final report

An investigation from the Bureau Permanent d’Enquêtes d’Accidents et Incidents d’Aviation of the DRC Ministry of Transport and Channels of Communication found that "[t]he most probable cause of the accident was the aircraft's encounter with a severe Microburst like weather phenomenon at a very low altitude during the process of Go Around. The severe vertical gust/downdraft caused a significant and sudden pitch change to the aircraft which resulted in a considerable loss of height. Being at very low altitude, recovery from such a disturbance was not possible."[16]

Nationalities of the victims

| Nationality | Fatalities | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passengers | Crew | ||

| 8[17] | 0 | 8 | |

| 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| 3[18] | 0 | 3 | |

| 2[19] | 0 | 2 | |

| 2[17] | 0 | 2 | |

| 1[20] | 0 | 1 | |

| 1[17] | 0 | 1 | |

| 1[21] | 0 | 1 | |

| 1[21] | 0 | 1 | |

| 1[17] | 0 | 1 | |

| 1[17] | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Total Fatalities: | 32 | ||

See also

- List of accidents and incidents involving airliners by location

- Microburst

- Si Fly Flight 3275, a UN-chartered plane crash in Kosovo

- Specific incidents

Notes

A^ The METAR in force at the time was FZAA 041300Z 18020KT 0500 +TSRA SCT022 SCT028CB BKN110 28/22 Q1008 CB SECT NE-E-SE-W BECMG 1500/[6]

This translates as METAR for N'djili Airport, issued on the 4th of the month at 13:00 Zulu time. Winds from 180° at 20 knots (37 km/h). Visibility 500 metres (550 yd). Thunderstorms and heavy rain showers (greater than 7.6 mm/h). Scattered (cumulative 3⁄8 of sky covered) clouds at 2,200 feet (670 m), Scattered (cumulative total now 4⁄8) thunderclouds at 2,800 feet (850 m), broken (cumulative total between 5⁄8 to 7⁄8) clouds at 11,000 feet (3,400 m). Temperature 28 °C (82 °F), dew point 22 °C (72 °F), QNH 1008 hPa, thunderstorms to north east, east, south east and west of airport, visibility expected to improve to 1,500 metres (1,600 yd), end of report.

References

- ↑ "Dozens killed in DR Congo plane crash". Al Jazeera. 5 April 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Fatal UN plane crash at DR Congo's Kinshasa airport". BBC News. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 "4L-GAE Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "Sole survivor describes Congo crash". Television New Zealand. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011.

- ↑ "Canadair Regional Jet – MSN 7070". Airfleets. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hradecky, Simon (4 April 2011). "Crash: Georgian Airways CRJ1 at Kinshasa on Apr 4th 2011, missed the runway and broke up". Aviation Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "Kinshasa: un avion de la Monusco s'écrase à l'aéroport de N'djili" (in French). Radio Okapi. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "Au moins 16 morts dans l'accident d'un avion de l'ONU au RD Congo" (in French). AFP via Google. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Kron, Josh (4 April 2011). "U.N. Plane Crashes in Congo, Killing 32". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "More than 30 people perish in UN plane crash in DR Congo". United Nations. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "UN Congo crash sole survivor says plane battered". Reuters. 5 April 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- 1 2 Yeo, Ghim-Lay. "Georgian Airways CRJ100 crashes on UN mission flight". Flight International. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ "UN Security Council conveys "deepest condolences" to those killed in DRC plane crash". xinhuanet. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "Top UN officials express sorrow after deadly plane crash in DR Congo". UN News Centre. 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "US sends condolences after DR Congo plane crash". AFP. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 investigation

- 1 2 3 4 5 More UN plane crash victims named as investigation into cause continues

- ↑ "SA men killed in Congo crash". IOL.co.za. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ Vanackere, Stephen. "Deadly MONUSCO plane crash in the DRC". Polwire. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ "Congo-Kinshasa: Plane Crash Takes the Life of Dr. Boubacar Toure". AllAfrica.com. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Black box found after UN plane tragedy in Congo". The New Age Online. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

External links

- "INVESTIGATION REPORT OF ACCIDENT INVOLVING GEORGIAN AIRWAYS AIRCRAFT CRJ-100ER (4L-GAE) AT KINSHASA’S N’DJILI AIRPORT DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC) ON 04 APRIL 2011" (Archive) - Bureau Permanent d’Enquêtes d’Accidents et Incidents d’Aviation, Ministry of Transport and Channels of Communication - English translation

- (in French) "RAPPORT FINAL D’ENQUETE TECHNIQUE SUR L’ACCIDENT DE L’AVION CRJ-100, IMMATRICULE 4L-GAE" (Archive) - Bureau Permanent d’Enquêtes d’Accidents et Incidents d’Aviation, Ministry of Transport and Channels of Communication - Original version