1962 in the Vietnam War

| 1962 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 53 killed South Vietnam: 4,457 killed[1] | North Vietnam: casualties | ||

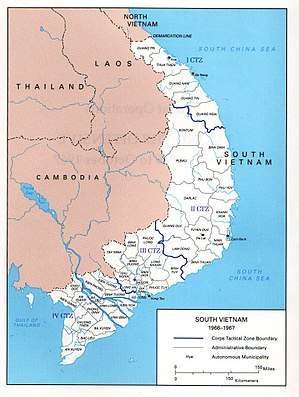

The Viet Cong insurgency expanded in South Vietnam in 1962. U.S. military personnel flew combat missions and accompanied South Vietnamese soldiers in ground operations to find and defeat the insurgents. Secrecy was the official U.S. policy concerning the extent of U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam. The U.S.'s commanding general of MACV, Paul D. Harkins, projected optimism that progress was being made in the war, but that optimism was refuted by the concerns expressed by a large number of more junior officers and civilians. Several prominent magazines, newspapers, and politicians in the U.S. questioned the military strategy the U.S. was pursuing in support of the South Vietnamese government of President Ngô Đình Diệm. Diệm created the Strategic Hamlet Program as his top priority to defeat the Viet Cong. The program intended to cluster South Vietnam's rural dwellers into defended villages where they would be provided with government social services.

North Vietnam increased its support to the Viet Cong, infiltrating men and supplies into South Vietnam via the Ho Chi Minh trail. North Vietnam proposed negotiations to neutralize South Vietnam as had been done in neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but the failure of the Laotian neutrality agreement doomed that initiative.

US analyses and statements about progress and problems with the war often conflicted or contradicted each other which is reflected in this article.

January

- 3 January

The first U.S. military transport aircraft arrived in South Vietnam. The aircraft would be used to transport South Vietnamese soldiers.[2]

- 4 January

Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric recommended to General Lyman Lemnitzer, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, that for military operations involving Americans in South Vietnam The Pentagon develop a "suitable cover story, or stories, a public explanation, a statement of no comment...for approval of the Secretary of Defense."[3]

- 10 January

The first Operation Ranch Hand mission began. Defoliants (Agent Orange) were sprayed from U.S. aircraft along several miles of Highway 15 leading from the port of Vũng Tàu to the airforce base at Biên Hòa near Saigon. Although the United States wished to keep the use of defoliants secret, the South Vietnamese government announced publicly that defoliants supplied by the U.S. were being used to kill vegetation near highway routes.[4]

- 12 January

Operation Chopper was the first combat operation for American soldiers in Vietnam. U.S. pilots transported about 1,000 South Vietnamese soldiers by helicopter to land and attack Viet Cong guerrillas about 10 miles west of Saigon. The operation was deemed a success. Chopper heralded a new era of air mobility for the U.S. Army, which had been growing as a concept since the Army formed twelve helicopter battalions in 1952 during the Korean War.

U.S. President John F. Kennedy said only that the U.S. was helping the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) with "training and transportation." He declined to offer more details about Operation Chopper to avoid "assisting the enemy."[5]

- 15 January

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara met with his top military advisers. CINCPAC intelligence told him that the Viet Cong now numbered 20,000 to 25,000 and were increasing by 1,000 per month after casualties. South Vietnam's armed forces had suffered more than 1,000 casualties in the previous month, most by the paramilitary Self Defense Corps. McNamara ordered sending 40,000 M-1 carbines to Vietnam to arm the Self Defense Corps and the Civil Guard, although those two organizations were the sources of many of the Viet Cong's captured weapons.

McNamara pressed for a "clear and hold" operation in a single South Vietnamese province. Clear and hold envisioned the ARVN securing the province followed by civic and political action to exclude the Viet Cong permanently. Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) chief General Lionel C. McGarr proposed instead using 2 ARVN divisions in a conventional military sweep focused on killing Viet Cong but without the followup to hold the area.[6]

- 20 January

Admiral Harry D. Felt, CINCPAC commander, authorized American advisers to accompany South Vietnamese military forces on combat operations.[7]

February

- 2 February

Roger Hilsman, a U.S. State Department official with World War II experience in guerrilla war, submitted a paper entitled "A Strategic Concept for South Vietnam" to President Kennedy and General Taylor. Drawing heavily on British adviser Robert Grainger Ker Thompson's plan for strategic hamlets, Hilsman said "the struggle for South Vietnam...is essentially a battle for control of the villages." He stated that "the problem presented by the Viet Cong is a political and not a military problem, and that to be effective counterinsurgency "must provide the people and the villages with protection and physical security." Hilsman's solution to this problem was similar to that of Thompson's.

Hilsman advocated that the South Vietnamese army adopt tactics of mobility, surprise, and small unit operations. Conventional warfare such as the use of artillery or aerial bombardment to soften up the enemy will "only give advance warning of an operation, permit the Viet Cong to escape, and inevitably result in the death of uncommitted or wavering civilians whose support is essential for the Viet Cong's ultimate defeat."[8]

- 3 February

President Diệm created by presidential decree the strategic hamlet program. President Diệm's brother, Ngô Đình Nhu, headed the program. The plans called for rural people to provide manpower and labor to build and defend the strategic hamlets. It was an ambitious program which projected that 7,000 strategic hamlets would be built by the end of 1962 and 12,000 by the end of 1963, thus consolidating nearly all the rural population of South Vietnam.[9]

- 8 February

The Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) was created to support and assist South Vietnam in defeating the Viet Cong insurgency. MAAG continued to exist, but only to train Vietnam's armed forces. General Paul D. Harkins, recommended by President Kennedy's military adviser, General Maxwell Taylor, was named MACV commander. Harkins and his staff had little or no counterinsurgency experience.[10]

Moreover, the counterinsurgency effort lacked a "single directing authority" and a "continuing, authoritative interagency oversight." The MACV commander did not have control of the entire counterinsurgency effort and MACV "labored under complex command relationships and had to thread its way through intractable interservice conflicts over fine points of organization, staffing, and doctrine. MACV commander Harkins reported to CINCPAC Chief, Admiral Harry D. Felt who kept MACV "on a tight rein." [11]

- 14 February

Journalist James Reston published an article in The New York Times stating that "The United States is now involved in an undeclared war in South Vietnam. This is well known to the Russians, the Chinese Communists, and everybody else concerned except the American people....Has the President made clear to the Congress and the nation the extent of the U.S. commitment to the South Vietnam government and the dangers involved?"[12]

- 18 February

North Vietnam contacted diplomats from the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, co-chairs of the Geneva Accords of 1954. requesting that they "urgently study effective measures to end U.S. aggression in South Vietnam." Later, North Vietnam requested that the UK and USSR "proceed to consultations with the interested countries to seek effective means of preserving the Geneva settlement of 1954 and safeguarding peace." [13]

- 20 February

Senator Wayne Morse said in a Senate Hearing closed to the public, "when those ships start coming back to the west coast with the flag-draped coffins of American boys, look out, because the American people, in my judgement are going to be very much divided....I have grave doubts as to the constitutionality of the President's course of action in South Vietnam."[14]

- 21 February

The Department of State cabled instructions about dealing with the media to the Embassy in Saigon. The instructions said that it was not in U.S. interest "to have stories indicating that Americans are leading and directing combat missions against the Viet Cong.[15]

A National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) by the CIA estimated Viet Cong numbers in South Vietnam. There were at least 25,000 full time fighters supported by 100,000 part time locals serving as village defense forces. The NIE estimated that 800 North Vietnamese officers and soldiers were in South Vietnam assisting the Viet Cong.[16]

- 26 February

Newsweek magazine asked the question: "Will the sending of U.S. troops lead to escalation, more guerrillas, more Americans, and an eventual confrontation of the U.S. and Red China? Above all can the U.S. strategy win the war?"[17]

- 27 February

Two South Vietnamese pilots flying U.S. warplanes bombed the Presidential Palace in Saigon to protest President's Diệm's priority on remaining in office rather than defeating the Viet Cong. Diệm and his family were uninjured.[18] One of the pilots was imprisoned; the other fled to Cambodia. Both returned to duty after Diệm's death.[19]

March

- 1 March

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) estimated that the Viet Cong numbered 20,000 full-time guerrillas, up from 4,000 two years earlier. DOD estimated that the Viet Cong controlled 10 percent of South Vietnam's hamlets and had influence in another 60 percent. In the cities, however, Viet Cong influence was minimal and the Montagnard people of the Central Highlands supported neither the government or the communists. The bulk of the Viet Cong fighters were located in the Mekong Delta and near Saigon.

DOD identified three types of Viet Cong fighters. First the main forces were well armed and used only on large operations; second were the provincial and district units, a mixture of guerrillas and organized units; and third, not part of the 20,000 estimate, were the part-time guerrillas, often armed only with primitive weapons but important for intelligence, logistics, and terrorist operations. Five hundred to 1,000 men monthly were estimated to be infiltrating South Vietnam from North Vietnam.[20]

- 6 March

The People's Republic of China called for an international conference to seek peace in South Vietnam. Cambodia and the Soviet Union supported the proposal. Negotiations in Geneva to create a neutralist coalition government in Laos seemed the inspiration for proposals by North Vietnam, its allies, and neutral Cambodia to seek the convening of a conference.[21]

- 12 March

The New Republic magazine said, "The US has 'capitulated' to Diem and has bound itself to the defense of a client regime without exacting on its part sacrifices necessary for success. American lives are to be risked in a holding action based on the inexplicable hope that with sharpened-up counter-guerilla operations and marginal reforms the regime will last."[22]

- 19 March

Operation Sunrise was the first operation in the strategic hamlet program, carried out by ARVN with U.S. advice and transport assistance in the Ben Cat region of the Bình Dương Province, 25 miles (40 km) north of Saigon. The plan was to kill or expel Viet Cong guerrillas and relocate the rural people to four strategic hamlets. However, unlike Thompson's plan which contemplated beginning the strategic hamlet program in relatively secure areas, Bình Dương was heavily under the influence of the guerrillas, nearly all of whom had prior warning of the operation and escaped. The remaining inhabitants were rounded up and forcibly resettled in the strategic hamlets. To control the area, ARVN had to keep a large number of soldiers stationed in Ben Cat and the Viet Cong harassed both the army and the hamlets, bringing them under its control in 1964.[23]

- 26 March

Begun in November 1961 in the village of Buon Enao with 400 inhabitants, the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) project in Darlac province among the Montgnard peoples had expanded to cover 14,000 people with 972 village defenders and a 300-man strike force to combat Viet Cong guerrillas. The CIDG was supported by U.S. and South Vietnamese Special Forces and the CIA with Special Forces soldiers being assigned to villages to train the defenders. The project was managed by David A. Nuttle, an agriculture adviser from Kansas, ARVN Captain Nguyen Duc Phu, and Montagnard leader Y-Ju, the village chief of Buon Enao.[24]

- 29 March

The Joints Chiefs of Staff finalized instructions to MACV concerning "maximum discretion" and "minimum publicity" for U.S. air operations in South Vietnam. If an enemy aircraft was shot down, MACV was instructed to remain silent unless it became necessary to contradict communist propaganda in which case MACV was to say that while on a routine training flight, an unidentified airplane initiated hostile action and was shot down. If a U.S. airplane was lost, MACV was instructed to say that the aircraft was on a routine orientation flight and the cause of the accident is being investigated. MACV was further instructed to ensure that all knowledgeable personnel were "instructed and rehearsed" with these rules.[25]

May

- 8 May

Operation Sea Swallow began in Phú Yên Province in central South Vietnam. The objectives were similar to those of the March 19 Operation Sunrise. The goal was to build more than 80 strategic hamlets in the province before the end of 1960. As of 18 May, more than 600 Civic Action personnel had been trained in the province. Although relatively positive about the strategic hamlet program, Roger Hilsman reported to the State Department that the program suffered from "inadequate direction, coordination, and internal assistance...In the short run, the success of the effort will depend largely on the degree of physical security provided the peasantry, but in the long run the key to success will be the ability of the government to walk the thin line of meaningful and sustained assistance to the villagers without obvious efforts to direct, regiment, or control them."[26]

- 21 May

Lt. Col. John Paul Vann arrived in Mỹ Tho in the Mekong Delta 40 miles (64 km) south of Saigon as head of the U.S. advisory mission to the ARVN's 7th division based in Mỹ Tho. The southern one-half of the delta was under Viet Cong control and the northern one-half was contested. Vann would become the best known of all U.S. military and civilian advisers in South Vietnam and would spend most of the next 10 years in the country.[27]

- 26 May

General William B. Rosson who had recently visited Buon Enao and the CIDG program in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam told General Maxwell Taylor, President Kennedy's military adviser, that the Special Forces soldiers assigned to CIDG were being used "improperly" and that they should be engaged in offensive operations. Rosson's opposition to Buon Enao was especially significant because he was the U.S. Army's Director of Special Operations which oversaw the Special Forces.[28]

June

- 6 June

President Kennedy spoke to the graduating class at West Point attempting to instill in them his emphasis on counterinsurgency: "This is another type of war, new in its intensity, ancient in its origin--war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins, war by ambush instead of by combat; by infiltration, instead of aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him....It requires...a whole new kind of strategy, a wholly different kind of force, and therefore a new and wholly different kind of military training."[29]

- 8 June

Senator Wayne Morse went public with his criticism of the Vietnam War. "I have heard no evidence which convinces me that it would be militarily wise to get bogged down anywhere in Asia in a conventional war."[30]

- 10 June

Senator Mike Mansfield became the first prominent Democrat to question U.S. policy in Vietnam. Mansfield, an early supporter of President Diệm and the most knowledgeable Senator on Vietnam, called for Diệm to put more emphasis on political and economic development—-as had been emphasized to Diệm "for many years." He advocated a greater use of diplomacy by the United States and less emphasis on military aid.[31]

July

(approximate date) North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh visited China. He told the Chinese that the United States might attack North Vietnam. China was alarmed by his statement and offered to equip 230 battalions (more than 100,000 soldiers) of the North Vietnamese army.[32]

- 16 July

Journalist Bernard Fall met with Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng and Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi. Dong said "we do not want to give pretexts that could lead to an American military intervention in the South." Fall expressed the view that the North Vietnamese would accept a neutralist government in South Vietnam to end U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam, provided that the government did not include President Diệm. That same month, North Vietnamese official Lê Duẩn instructed the leadership of the Viet Cong to avoid escalating the war by attacking cities as that might cause the United States to intervene in the war.[33]

- 19 July

The National Liberation Front in South Vietnam proposed to end the war in South Vietnam with a ceasefire, the withdrawal of American soldiers, and the creation of a coalition government of all factions pending elections. South Vietnam would become a neutral country, as were Cambodia and Laos, guaranteed by international treaty.[34]

- 23 July

The CIA had requested an increase in Special Forces soldiers to 400 to expand the CIDG program among the Montagnards in the Central Highlands. Instead, Secretary of Defense McNamara and MACV commander General Harkins transferred responsibility for CIDG from CIA to the Department of Defense which wanted the Special Forces "used in conjunction with active and offensive operations, as opposed to support of static training activities." The transfer of responsibility was called Operation Switchback.[35]

A factor possibly influencing the takeover by DOD of the CIDG program was the concern of President Diệm. He was afraid that the Montagnards in Darlac, having gained weapons, training, and organization under CIDG, might demand autonomy within South Vietnam. Diệm demanded that the Montagnards be disarmed and be under the control of provincial authorities appointed by him.[36]

General Harkins told a meeting of Secretary of Defense McNamara and U.S. military leaders in Hawaii that "there is no doubt we are on the winning side." He predicted that it would take about one year for MACV to develop the South Vietnamese military forces to the point where they could fully engage the Viet Cong. McNamara was more cautious stating that he thought it would take three years to get the Viet Cong insurgency under control.[37]

The Geneva Agreement on Laos was signed by 14 countries, including China, the Soviet Union, and the United States. The agreement declared a cease fire between the Royal Lao government and the communist Pathet Lao guerrillas and aimed to maintain Laos as a neutral country with a coalition government. What resulted instead was a resumption of the civil war and a de facto partition of the country with the government controlling the western one-half of the country and the Pathet Lao the eastern one half. The Ho Chi Minh trail was in territory controlled by the Pathet Lao.[38]

August

- 3 August

An Australian analysis of North Vietnam's proposal for the neutralization of South Vietnam concluded that President Diệm was "unlikely...to agree to internal negotiations for the withdrawal of United States military aid and the neutralization of South Vietnam." Thus, Hanoi was exploiting international opinion by appearing to be open to negotiations. The failure of the Geneva Agreement on Laos and the outbreak of hostilities between the Royal Lao Government, supported by the U.S., and the communist Pathet Lao, supported by North Vietnam, in the summer of 1962 destroyed whatever faith that North Vietnam had in negotiations with the United States and South Vietnam and strengthened the militants, notably Lê Duẩn, in their conviction that Vietnam would only be united by military action.[39]

September

- 11 September

In a briefing for President Kennedy's military adviser, General Maxwell Taylor in Saigon, Colonel Vann attempted to present his views that the war was going badly, but General Harkins overrode or refuted him. Vann believed that the ARVN was too passive and that indiscriminate bombing, by both South Vietnamese and American pilots, of villages and hamlets was counterproductive, aiding the Viet Cong in gaining recruits. He also believed that too many American arms provided to the South Vietnamese army and security forces were ending up in the hands of the Viet Cong, thus contributing to their growth in numbers.[40]

- 20 September

After his visit to Vietnam, General Taylor returned to Washington. His report was optimistic, citing progress in implementing the strategic hamlet program and training ARVN, improved performances by the paramilitary Civil Guard and Self-Defense Forces, and a larger area of territory under the control of South Vietnam. He also cited problems with intelligence, South Vietnam's lack of a counterinsurgency plan, and continued infiltration of men and supplies from North Vietnam.[41]

October

The Buon Enao experiment in Darlac province (the CIDG project) now counted about 200 Montagnard villages with a population of 60,000 people joined to resist the Viet Cong. They were protected by 10,600 defenders and 1,500 strike force personnel. Both the defenders and strike force personnel were themselves villagers. The U.S. Special Forces had four soldiers in each of six Area Development Centers responsible for both civic and paramilitary action. Firefights between the Viet Cong and the villages were nearly daily occurrences. About 50 villagers were killed by the Viet Cong during 1962; Viet Cong casualties were estimated at 200 killed and 460 captured. Buon Enao was considered by some senior U.S. military officers as the most impressive American accomplishment achieved until then in South Vietnam.[42]

However, the transfer of responsibility for the CIDG from the CIA to the U.S. Defense Department under Operation Switchover would soon destroy the effectiveness of the program as U.S. Special Forces were increasingly assigned purely military missions.[43]

- 1 October

General Maxwell Taylor was named by President Kennedy to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- 9 October

After being deluged with more than 200 visitors from the U.S. Department of Defense in the previous month—all requiring food, housing, entertainment, and visits to the countryside to see the war—General Taylor issued a directive to "reduce the number of visitors...to those having actual business of pressing interest." The directive only temporarily reduced the number of visitors.[44]

- 20 October

Journalist David Halberstam wrote in The New York Times that "the closer one gets to the actual contact level of the war, the further one gets from official optimism."[45]

November

- 14 November

A Situation Report prepared at The Pentagon expressed satisfaction at progress being made in South Vietnam. The ARVN was becoming more effective; Viet Cong activity was diminishing. The ARVN now numbered 219,000, the Civil Guard 77,000, and the Self Defense Corps 99,500. In South Vietnam, the U.S. had 11,000 'advisers', 300 aircraft, 120 helicopters, heavy weapons, pilots flying combat missions, defoliants, and napalm.[46]

- 30 November

Senator Mike Mansfield arrived in Saigon as head of a congressional fact-finding delegation. Ambassador Nolting and General Harkins gave the delegation optimistic briefings on the military situation in South Vietnam. "We can see the light at the end of the tunnel", said Nolting. Mansfield had been an early supporter of Diệm, but found him on this occasion "gradually being cut off from reality." He met with an "aggressive" Madame Nhu and her husband Ngô Đình Nhu who touted the Strategic Hamlet Program. Mansfield's meeting with journalists, however, revealed a different and much more pessimistic view of Vietnam. Embassy Deputy Chief of Mission William Trueheart hinted to Mansfield that the journalists' view was correct.[47]

December

- 10 December

The Politburo of North Vietnam assessed the progress of the insurgency in South Vietnam, in a meeting from 6 to 10 December. Although the Viet Cong had achieved many successes, they were still not able to counter American and ARVN mobility. The Viet Cong were tasked with studying how they could overcome that mobility. Political and military struggle was still rudimentary in South Vietnam and liberated areas were small. A priority for the Viet Cong was to destroy the strategic hamlet program with an expanded insurgency. Military Transportation Group 559 was instructed to build a road through Laos to facilitate the transportation of greater quantities of arms and supplies from North Vietnam to the Viet Cong.[48]

- 26 December

Senator Mansfield gave Kennedy a copy of his lengthy report on South Vietnam and briefed the President. Mansfield concluded that little progress had been made by Diệm, politically or militarily, since the Geneva Accords of 1954. Diệm had also made little progress in gaining popular support in the countryside, which by night was ruled largely by the Viet Cong. It "wasn't a pretty picture" that Mansfield presented to Kennedy, who disagreed with some of Mansfield's opinions.[49]

- 27 December

The reports of several American military officers who had visited Vietnam were mostly pessimistic. They said that President Diệm's control of the ARVN extended to refusing to arm certain units because he feared they would attempt a coup d'état against him. Regarding the performance of ARVN, one officer said it was "proficient at attacking an open rice field with nothing in it and....quickly bypassing any heavily wooded area that might possible contain a few VC [Viet Cong]." The reports were given to Marine Corps general Victor Krulak, who was preparing to visit South Vietnam as part of a high-level U.S. military mission to assess progress in the war.[50]

- 31 December

North Vietnam infiltrated 12,850 persons into South Vietnam, mostly southern communists who had migrated to North Vietnam in 1954–1955.[51] 53 American soldiers were killed in Vietnam during the year, compared to 16 in 1961.[52] The South Vietnamese armed forces suffered 4,457 killed in action, 10 percent more than the total killed in the previous year.[53]

Notes

- ↑ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965-1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- ↑ Daugherty, Leo (2002), The Vietnam War Day by Day, New York: Chartwell Books, Inc., p. 23

- ↑ Newman, John M., JFK and Vietnam: Deception, Intrigue, and the Struggle for Power, New York: Warner Books, 1992, p. 205

- ↑ Buckingham, Jr., William A. (1982), Operation Ranch Hand: The Air Force and Herbicides in Southeast Asia 1961-1971, Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, pp. 32-36

- ↑ "On This Day: America begins first combat operation in Vietnam War" http://uk.news.yahoo.com/on-this-day-america-begins-first-combat-operation-in-vietnam-war-153329849.html#ORNfMSk, accessed 3 Sep 2014

- ↑ Newman, John M., JFK and Vietnam: Deception, Intrigue, and the Struggle for Power, New York: Warner Books, 1992, pp 175-178

- ↑ Daugherty, p. 24

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Vol. II, Vietnam, 1962, Document 42; The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Vol. 2, Chapter 2, "The Strategic Hamlet Program, 1961-1963", pp. 128-159

- ↑ Peoples, Curtis, "The Use of the British Village Resettlement Model in Malaya and Vietnam Texas Tech University, 4th Triennial Vietnam Symposium, 11–13 April 2002 http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/events/2002_Symposium/2002Papers_files/peoples.php, accessed 3 Sep 2014

- ↑ Krepenevich, Jr., Andrew F. The Army and Vietnam Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986, pp. 64-65

- ↑ Cosmas, pp. 28-29, 41

- ↑ Mann, Robert, A Grand Delusion: America's Descent into Vietnam, New York: Basic Books, 2001, p. 257

- ↑ Asselin, Pierre, Hanoi's Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, p. 127

- ↑ Mann, pp. 259-260

- ↑ Newman, p. 206

- ↑ Newman, pp. 194-195

- ↑ Mann, p. 257

- ↑ Bowman, John S. (1985), The World Almanac of the Vietnam War, New York: Pharos Book, p. 55;

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1997), Vietnam: A history, New York: Penguin Books, pp. 280-281

- ↑ Cosmas, pp. 72-73

- ↑ Asselin, p. 127

- ↑ Mann, p. 262

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 67-69; Peoples, http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/events/2002_Symposium/2002Papers_files/peoples.php, accessed 3 Sep 2014

- ↑ Harris, J. P. "The Buon Enao Experiment and American Counterinsurgency", Sandhurst Occasional Papers, No. 13, 2013, pp. 15-25

- ↑ Newman, pp. 214-215

- ↑ Hilsman, Roger, "Progress Report on South Vietnam", in The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Vol. 2, pp. 673-681

- ↑ Sheehan, Neil, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam, New York: Vintage Books, 1988, pp. 1-43

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr., p. 31, 71

- ↑ http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8695, accessed 3 Sep 2014

- ↑ Mann, p. 267

- ↑ Mann, pp. 263-264

- ↑ Chen Jian (June 1995), " China's Involvement in the Vietnam War, 1964-69", The China Quarterly, No. 142, p. 359. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ↑ Asselin, p. 134; Logevall, Frederik, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p. 8

- ↑ Asselin, p. 136

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr., pp 71-72

- ↑ Harris, p. 29-30

- ↑ Buzzanco, Robert Masters of War" Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1996, p. 131

- ↑ Cosmas, Graham A. (2006), MACV The Joint Command in the Years of Escalation, 1962-1967, Center of Military History, United States Army, pp. 17-18

- ↑ Asselin, pp. 137-143

- ↑ Buzzanco, p. 131; Sheehan, Neil A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam New York: Vintage Books, 1988, pp 98-100

- ↑ Buzzanco, p. 134

- ↑ Harris, pp. 25-29

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 72-73; Nagi, John A. Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 128-129

- ↑ Cosmas, p. 41

- ↑ Buzzanco, p. 131

- ↑ Buzzanco, p. 136

- ↑ Mann, pp 270-273

- ↑ Ang Cheng Guan, "The Vietnam War, 1962–1964: The Vietnamese Communist Perspective", Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Oct. 2000), pp. 66–67

- ↑ Mann, pp. 273–276

- ↑ Buzzanco, p. 132

- ↑ Asselin, p. 243

- ↑ "Statistical Information about American Casualties in the Vietnam War", https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html, accessed 2 Sep 1014

- ↑ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965-1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

References

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A History. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2000). Our Vietnam. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81202-9.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-040-9.

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

| Vietnam War timeline |

|---|

|

↓HCM trail established ↓NLF Formed ↓Laos Bombing Begin ↓US Forces Deployed ↓Sihanouk Trail Created ↓PRG Formed │ 1955 │ 1956 │ 1957 │ 1958 │ 1959 │ 1960 │ 1961 │ 1962 │ 1963 │ 1964 │ 1965 │ 1966 │ 1967 │ 1968 │ 1969 │ 1970 │ 1971 │ 1972 │ 1973 │ 1974 │ 1975 |