Öljaitü

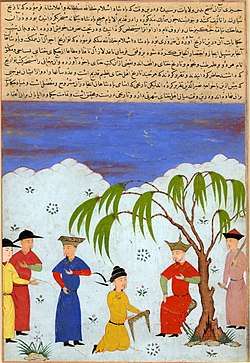

Öljeitü, Oljeitu, Olcayto or Uljeitu, Öljaitu, Ölziit (Mongolian: ᠦᠯᠵᠡᠢᠲᠦ ᠺᠬᠠᠨ, translit. Öljeitü Ilkhan, Өлзийт хаан), also known as Muhammad Khodabandeh (Persian: محمد خدابنده - اولجایتو, khodābandeh from Persian meaning the "slave of God" or "servant of God"; 1280 – December 16, 1316), was the eighth Ilkhanid dynasty ruler from 1304 to 1316 in Tabriz, Iran. His name "Ölziit" means "blessed" in the Mongolian language.

He was the son of the Ilkhan ruler Arghun, brother and successor of Mahmud Ghazan (5th successor of Genghis Khan), and great-grandson of the Ilkhanate founder Hulagu.

Life

Oljeitu was the son of Arghun's third wife, the Christian Uruk Khatun.[1] Oljeitu was baptised as a Christian and received the name Nikolya (Nicholas) after Pope Nicholas IV.[2] During his youth he converted to Buddhism and later to Sunni Islam along with his brother Ghazan. He later converted to Shi'a Islam after coming into contact with Shi'a scholars,[3] although another source indicates he converted to Islam through the persuasions of his wife.[4] He changed his first name to the Islamic name Muhammad. Some of his relatives and companions gave him a nickname of Khutabanda. Rashid al-Din wrote that he adopted the name Oljeitu following Yuan emperor Oljeitu Temür enthroned in Dadu. But some Muslim source mentions that it rained when he was born, and delighted Mongols called him Mongolian name Öljeitu (Өлзийт), meaning auspicious.

After succeeding his brother, Öljeitu became influenced by Shi'a theologians Al-Hilli and Maitham Al Bahrani.[5] In 1306, Oljeitu founded the city of Soltaniyeh,[6] and upon Al-Hilli's death, Oljeitu transferred his teacher's remains from Baghdad to a domed shrine he built in Soltaniyeh. Later, alienated by the factional strife between the Hanafis and the Shafis, Oljeitu changed his sect to Shi'a Islam in 1310, believing it to be the true version of Islam.[7] Mirkhond reportedly claims he started the custom of taking children from Christian and Jewish families to be raised as Muslims, analogous to the later Ottoman system of Devshirme.[6]

In 1309, Öljeitu founded a Dar al-Sayyedah ("Sayyed's lodge") in Shiraz, Iran, and endowed it with an income of 10,000 Dinars a year.

He died in Soltaniyeh, near Zanjan, in 1316, having reigned for twelve years and nine months.[6] Afterwards, Rashid al-Din Hamadani was accused of having caused his death by poisoning and was executed. Oljeitu was succeeded by his son Abu Sa'id. His magnificent tomb in Soltaniyeh, 300 km west of Tehran, remains the best known monument of Ilkhanid Persia.

Relations with Europe

Trade contacts

Trading contacts with European powers were very active during the reign of Öljeitu. The Genoese had first appeared in the capital of Tabriz in 1280, and they maintained a resident Consul by 1304. Oljeitu also gave full trading rights to the Venetians through a treaty in 1306 (another such treaty with his son Abu Said was signed in 1320).[8] According to Marco Polo, Tabriz was specialized in the production of gold and silk, and Western merchants could purchase precious stones in quantities.[8]

Military alliance

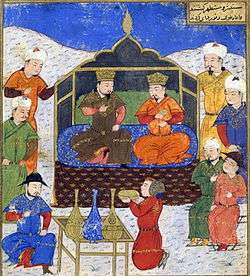

After his predecessor Arghun, Öljeitu continued diplomatic overtures with the West, and re-stated Mongol hopes for an alliance between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks, even though Öljeitu himself had converted to Islam.

1305 embassy

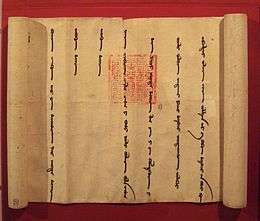

In April 1305, he sent a Mongol embassy led by Buscarello de Ghizolfi to the French king Philip IV of France,[9] Pope Clement V, and Edward I of England. The letter to Philip IV, the only one to have survived, describes the virtues of concord between the Mongols and the Franks:

"We, Sultan Oljaitu. We speak. We, who by the strength of the Sky, rose to the throne (...), we, descendant of Genghis Khan (...). In truth, there cannot be anything better than concord. If anybody was not in concord with either you or ourselves, then we would defend ourselves together. Let the Sky decide!"

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.[10]

He also explained that internal conflicts between the Mongols were now over:

"Now all of us, Timur Khagan, Tchapar, Toctoga, Togba and ourselves, main descendants of Gengis-Khan, all of us, descendants and brothers, are reconciled through the inspiration and the help of God. So that, from Nangkiyan (China) in the Orient, to Lake Dala our people are united and the roads are open."

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.[11]

This message reassured the European nations that the Franco-Mongol alliance, or at least attempts towards such an alliance, had not ceased, even though the Khans had converted to Islam.[12]

1307 embassy

Another embassy was sent to the West in 1307, led by Tommaso Ugi di Siena, an Italian described as Öljeitu's ildüchi ("Sword-bearer").[13] This embassy encouraged Pope Clement V to speak in 1307 of the strong possibility that the Mongols could remit the Holy Land to the Christians, and to declare that the Mongol embassy from Öljeitu "cheered him like spiritual sustenance".[14] Relations were quite warm: in 1307, the Pope named John of Montecorvino the first Archbishop of Khanbalik and Patriarch of the Orient.[15]

European nations accordingly prepared a crusade, but were delayed. A memorandum drafted by the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitallers Guillaume de Villaret about military plans for a Crusade envisaged a Mongol invasion of Syria as a preliminary to a Western intervention (1307/8).[16] A corps of Frank mangonel specialists is known to have accompanied the Ilkhanid army in the conquest of Herat in 1307.[17] Mongols besieged the castle in Gilan for so long, that epidemic and lack of food supply forced Gilans to submit to them. He punished Kartids in Herat as well.

Military operation of 1308

Byzantine Emperor Andronicus II gave a daughter in marriage to Oljeitu and asked ilkhan's assistance against growing power of the Ottomans. In 1305, Oljeitu promised his father in law 40,000 men, and in 1308 dispatched 30,000 men to recover many Byzantine towns in Bithynia and the Ilkhanid army crushed a detachment of Osman I.[18]

1313 embassy

On April 4, 1312, a Crusade was promulgated by Pope Clement V at the Council of Vienne. Another embassy was sent by Oljeitu to the West and to Edward II in 1313.[19] That same year, the French king Philippe le Bel "took the cross", making the vow to go on a Crusade in the Levant, thus responding to Clement V's call for a Crusade. He was however warned against leaving by Enguerrand de Marigny,[20] and died soon after in a hunting accident.[21]

Öljeitu finally launched a last campaign against the Mamluks (1312–13), in which he was unsuccessful, though he reportedly briefly took Damascus.[6] A final settlement with the Mamluks would only be found when Oljeitu's son signed the Treaty of Aleppo with the Mamluks in 1322.

Family

- Consorts

Öljaitü had thirteen consorts:

- Terjughan Khatun, daughter of Legai Kurkan and Baba Khatun;

- Eltuzmish Khatun (m. 1296, died October/November 1308), daughter of Qutlugh Timur Kurkan of the Qonqirut tribe, sister of Taraqai Kurkan, and widow of Abaqa Khan and previously that of Gaykhatu Khan;

- Hajji Khatun, daughter of Chichak, son of Sulamish and Todogaj Khatun;

- Qutlugh Shah Khatun (m. 20 June 1305), daughter of Irinjin,[22] and Konchak Khatun;

- Bulughan Khatun Khurasani (m. 23 June 1305), daughter of Tasu and Mangli Tegin Khatun, and widow of Ghazan Khan;

- Kunjuskab Khatun (m. 1305), daughter of Shadi Kurkan and Orqudaq Khatun, widow of Ghazan Khan;

- Oljatai Khatun (died 4 October 1315), daughter of Sulamish and Todogaj Khatun, sister of Hajji Khatun, and widow of Arghun Khan;

- Soyurghatmish Khatun, daughter of Amir Husayn Jalayir, and sister of Hasan Buzurg;

- Qongtai Khatun, daughter of Timur Kurkan;

- Dunya Khatun, daughter of al-Malik al-Malik Najm ad-Din Ghazi, ruler of Mardin;

- Adil Shah Khatun, daughter of Amir Sartaq, the amir-ordu of Bulughan Khatun Buzurg;[23]

- Despina Khatun, daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos;[24]

- Tugha Khatun, a lady accused of having an affair with Demasq Kaja;

- Sons

Öljaitü had six sons:

- Bastam (1297 - 1309) - with Eltuzmish Khatun;

- Bayazid (1300 - 1308) - with Eltuzmish Khatun;

- Tayghur - with Eltuzmish Khatun;

- Sulayman Shah - with Adil Shah Khatun;

- Abu'l Khayr - with Oljatai Khatun;

- Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan - with Hajji Khatun;

- Daughters

Öljaitü had three daughters:

- Dowlandi Khatun (died 1314) - with Terjughan Khatun, married on 30 September 1305 to Amir Chupan;

- Sati Beg Khatun - with Eltuzmish Khatun, married firstly on 6 September 1319 to Amir Chupan, married secondly in 1336 to Arpa Ke'un, married thirdly in 1339 to Suleiman Khan;

- Sultan Khatun - with Qutlugh Shah Khatun;

Genealogy

- Genghis Khan

- Tolui

- Hulagu Khan

- Abaqa

- Arghun

- Öljaitü

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ryan, James D. (November 1998). "Christian wives of Mongol khans: Tartar queens and missionary expectations in Asia". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 8 (9): 411&ndash, 421. doi:10.1017/s1356186300010506.

- ↑ "Arghun had one of his sons baptized, Khordabandah, the future Öljeitu, and in the Pope's honor, went as far as giving him the name Nicholas", Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Jean-Paul Roux, p.408

- ↑ Alizadeh, Saeed; Alireza Pahlavani; Ali Sadrnia. Iran: A Chronological History. p. 137.

- ↑ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 197

- ↑ Al Oraibi, Ali (2001). "Rationalism in the school of Bahrain: a historical perspective". In Lynda Clarke. Shīʻite Heritage: Essays on Classical and Modern Traditions. Global Academic Publishing. p. 336.

- 1 2 3 4 Stevens, John. The history of Persia. Containing, the lives and memorable actions of its kings from the first erecting of that monarchy to this time; an exact Description of all its Dominions; a curious Account of India, China, Tartary, Kermon, Arabia, Nixabur, and the Islands of Ceylon and Timor; as also of all Cities occasionally mentioned, as Schiras, Samarkand, Bokara, &c. Manners and Customs of those People, Persian Worshippers of Fire; Plants, Beasts, Product, and Trade. With many instructive and pleasant digressions, being remarkable Stories or Passages, occasionally occurring, as Strange Burials; Burning of the Dead; Liquors of several Countries; Hunting; Fishing; Practice of Physick; famous Physicians in the East; Actions of Tamerlan, &c. To which is added, an abridgment of the lives of the kings of Harmuz, or Ormuz. The Persian history written in Arabick, by Mirkond, a famous Eastern Author that of Ormuz, by Torunxa, King of that Island, both of them translated into Spanish, by Antony Teixeira, who lived several Years in Persia and India; and now rendered into English.

- ↑ Curatola, Giovanni; Gianroberto Scarcia (2007). Iran: The Art and Architecture of Persia. Perseus Distribution Services. p. 166. ISBN 9780789209207.

- 1 2 Jackson, p.298

- ↑ Mostaert and Cleaves, pp. 56-57, Source

- ↑ Quoted in Jean-Paul Roux, Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, p.437

- ↑ Source

- ↑ Jean-Paul Roux, in Histoire de l'Empire Mongol ISBN 2-213-03164-9: "The Occident was reassured that the Mongol alliance had not ceased with the conversion of the Khans to Islam. However, this alliance could not have ceased. The Mamelouks, through their repeated military actions, were becoming a strong enough danger to force Iran to maintain relations with Europe.", p.437

- ↑ Peter Jackson, p.173

- ↑ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p.171

- ↑ Foltz, p.131

- ↑ Peter Jackson, p.185

- ↑ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p.315

- ↑ I. Heath, Byzantine Armies: AD 1118–1461, pp. 24–33.

- ↑ Peter Jackson, p.172

- ↑ Jean Richard, "Histoire des Croisades", p.485

- ↑ Richard, p.485

- ↑ Lambton, Ann K. S. (January 1, 1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia. SUNY Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-887-06133-2.

- ↑ Hillenbrand, Robert; Peacock, A. C. S.; Abdullaheva, Firuza (January 29, 2014). Ferdowsi, the Mongols and the History of Iran: Art, Literature and Culture from Early Islam to Qajar Persia. I. B. Tauris. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-780-76015-5.

- ↑ Korobeinikov, Dimitri (2014). Byzantium and the Turks in the Thirteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-198-70826-1.

References

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- ( ISBN 0-295-98391-4) page 87

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Jackson, Peter, The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education, ISBN 0-582-36896-0

- Roux, Jean-Paul, Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Fayard, ISBN 2-213-03164-9

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mahmud Ghazan |

Ilkhanid Dynasty 1304–1316 |

Succeeded by Abu Sa'id |