Mangonel

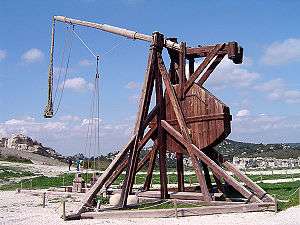

A mangonel[1][2][3], also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of catapult or siege engine used in China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia in the 6th century AD. Unlike the earlier torsion engines and later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel operated on manpower pulling cords attached to a lever and sling to launch projectiles. Although the mangonel required more men to function, it was also less complex and faster to reload than the torsion powered ballista and onager which it replaced in early Medieval Europe.[4][5][6]

Etymology and terminology

Mangonel is derived from the Greek mágganon, meaning "engine of war", but mangonel may also be indirectly referring to the mangon, a French hard stone found in the south of France. It may have been a name for counterweight artillery (trebuchets), possibly either a men-assisted fixed-counterweight type, or one with a particular type of frame.[7][8]

Terminology of the mangonel is often confused. The term itself was used as general medieval term for stone throwing artillery as well as the more specific traction trebuchet. However traction trebuchet is a modern term created to distinguish the mangonel from the onager, a torsion powered siege weapon that was superseded by the mangonel around the 6th century AD. The mangonel is often confused with the onager in translations, leading to further confusion, hence why modern military historians came up with "traction trebuchet", which was not known to contemporary users of the weapon.[9][10]

The mangonel is called al-manjanīq in Arabic. In China the traction trebuchet was called the pào (砲).[11]

History

The mangonel is thought to have originated in ancient China.[5][12][13] Torsion-based siege weapons such as the ballista and onager are not known to have been used in China.[14]

The first recorded use of mangonels was in ancient China. They were probably used by the Mohists as early as 4th century BC, descriptions of which can be found in the Mojing (compiled in the 4th century BC).[12][13] In Chapter 14 of the Mojing, the mangonel is described hurling hollowed out logs filled with burning charcoal at enemy troops.[15] The mangonel was carried westward by the Avars and appeared next in the eastern Mediterranean by the late 6th century AD, where it replaced torsion powered siege engines such as the ballista and onager due to its simpler design and faster rate of fire.[4][5][6] The Byzantines adopted the mangonel possibly as early as 587, the Persians in the early 7th century, and the Arabs in the second half of the 7th century.[14] The Franks and Saxons adopted the weapon in the 8th century.[16]

The catapult, the account of which has been translated from the Greek several times, was quadrangular, with a wide base but narrowing towards the top, using large iron rollers to which were fixed timber beams "similar to the beams of big houses", having at the back a sling, and at the front thick cables, enabling the arm to be raised and lowered, and which threw "enormous blocks into the air with a terrifying noise".[17]

— Peter Purton

The traction trebuchet displaced classical, torsion-powered artillery because it was simpler and required less competence to build, while maintaining comparable range and power, and it had far higher rates of firing and accuracy (when operated by a trained crew). Furthermore, it was probably safer to operate than tension weapons, whose bundles of taut sinews stored up huge amounts of energy even in resting state and were prone to catastrophic failure when in use.[18]

— Inge Ree Peterson

According to Leife Inge Ree Peterson, a mangonel could have been used at Theodosiopolis in 421 but was "likely an onager"[19]. He also claims that mangonels were independently invented or at least known in the Eastern Mediterranean by 500 AD based on records of different and better artillery weapons, however there is no explicit description of a traction trebuchet. Furthermore mangonels were used in Spain and Italy by the mid 6th century and in Africa by the 7th century. The Franks adopted the weapon in the 8th century.[20]

Thus, on the basis of fairly hard evidence of unknown machinery in Joshua the Stylite and Agathias, as well as good indications of its construction in Procopius (especially when read against Strategikon), it is likely that the traction trebuchet had become known in the eastern Mediterranean area at the latest by around 500. The philological and (admittedly circumstantial) historical evidence may even support a date around 400.[21]

— Inge Ree Peterson

West of China, the mangonel remained the primary siege weapon until the 12th century when it was replaced by the counterweight trebuchet.[22] In China the mangonel continued to be used until the counterweight trebuchet was introduced during the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty. In 617 Li Mi (Sui dynasty) constructed 300 mangonels for his assault on Luoyang, in 621 Li Shimin did the same at Luoyang, and onward into the Song dynasty when in 1161, mangonels operated by Song dynasty soldiers fired bombs of lime and sulphur against the ships of the Jin dynasty navy during the Battle of Caishi.[23][24]

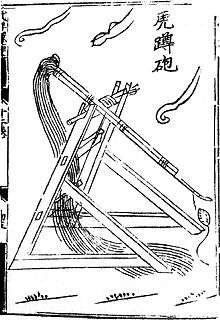

Crouching tiger trebuchet from the Wujing Zongyao

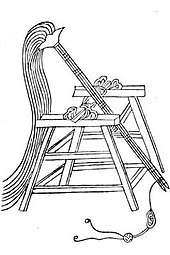

Crouching tiger trebuchet from the Wujing Zongyao Sìjiǎo "Four Footed" traction trebuchet from the Wujing Zongyao

Sìjiǎo "Four Footed" traction trebuchet from the Wujing Zongyao Traction trebuchet on a Song Dynasty warship from the Wujing Zongyao

Traction trebuchet on a Song Dynasty warship from the Wujing Zongyao 12th century depiction of a traction trebuchet (also called a perrier) next to a staff slinger

12th century depiction of a traction trebuchet (also called a perrier) next to a staff slinger Early 13th century Sicilian-Byzantine depiction of a traction trebuchet

Early 13th century Sicilian-Byzantine depiction of a traction trebuchet 13th century depiction of a traction trebuchet

13th century depiction of a traction trebuchet

See also

References

- ↑ "What is a catapult?". RLT Industries. Archived from the original on 2000-12-06. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ "Mangonel". middle-ages.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ from Old French or Norman mangonel(le), French mangoneau, itself from Medieval Latin manganellus, mangonellus, from Greek μάγγανον meaning "engine of war", "axis of a pulley". T. F. Hoad, The Concise Oxford Dictionary Of English Etymology, Oxford Paperbacks, Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 280a.

- 1 2 Purton 2009, p. 366.

- 1 2 3 Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American: 66–71. http://static.sewanee.edu/physics/PHYSICS103/trebuchet.pdf. Original version.

- 1 2 Graff 2016, p. 141.

- ↑ Konstantin Nossov; Vladimir Golubev. Ancient and Medieval Siege Weapons: A Fully Illustrated Guide to Siege Weapons and Tactics.

- ↑ Larry J. Simon; Robert Ignatius Burns; Paul E. Chevedden; Donald J. Kagay; Paul G. Padilla. Iberia and the Mediterranean World he Middle Ages: Studies in Honor of Robert I. Burns, S.J.

- ↑ Purton 2009, p. 365.

- ↑ Purton 2009, p. 410.

- ↑ Purton 2009, p. 411.

- 1 2 The Trebuchet, Citation:"The trebuchet, invented in China between the fifth and third centuries B.C.E., reached the Mediterranean by the sixth century C.E. "

- 1 2 PAUL E. CHEVEDDEN, The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion Archived 2014-06-10 at the Wayback Machine., p.71, p.74, See citation:"The traction trebuchet, invented by the Chinese sometime before the fourth century B.C." in page 74

- 1 2 Graff 2016, p. 86.

- ↑ Liang 2006.

- ↑ Purton 2009, p. 367.

- ↑ Purton 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Peterson 2013, p. 409.

- ↑ Peterson 2013, p. 275.

- ↑ Peterson 2013, p. 421-423.

- ↑ Peterson 2013, p. 421.

- ↑ Purton 2009, p. 29.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ↑ Franke, Herbert (1994). Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

Bibliography

- Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet" (PDF). Scientific American: 66–71. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-11. . Original version.

- Chevedden, Paul E. (2000). "The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 54: 71–116. doi:10.2307/1291833. JSTOR 1291833.

- Dennis, George (1998). "Byzantine Heavy Artillery: The Helepolis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (39).

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Gravett, Christopher (1990). Medieval Siege Warfare. Osprey Publishing.

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (April 1992). "Medieval Siege Engines Reconstructed: The Witch with Ropes for Hair". Military Illustrated (47): 15–20.

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (1992). "Experimental Reconstruction of the Medieval Trebuchet". Acta Archaeologica (63): 189–208. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03.

- Jahsman, William E.; MTA Associates (2000). The Counterweighted Trebuchet – an Excellent Example of Applied Retromechanics.

- Jahsman, William E.; MTA Associates (2001). FATAnalysis (PDF).

- Archbishop of Thessalonike, John I (1979). Miracula S. Demetrii, ed. P. Lemerle, Les plus anciens recueils des miracles de saint Demitrius et la penetration des slaves dans les Balkans. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Liang, Jieming (2006). Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity – An Illustrated History.

- Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilization in China. Cambridge University Press. p. 218.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Payne-Gallwey, Sir Ralph (1903). "LVIII The Trebuchet". The Crossbow With a Treatise on the Balista and Catapult of the Ancients and an Appendix on the Catapult, Balista and Turkish Bow (Reprint ed.). pp. 308–315.

- Peterson, Leif Inge Ree (2013), Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States, Brill

- Purton, Peter (2009), A History of the Early Medieval Siege c.450-1200, The Boydell Press

- Saimre, Tanel (2007), Trebuchet – a gravity operated siege engine. A Study in Experimental Archaeology (PDF)

- Siano, Donald B. (November 16, 2013). Trebuchet Mechanics (PDF).

- Al-Tarsusi (1947). Instruction of the masters on the means of deliverance from disasters in wars. Bodleian MS Hunt. 264. ed. Cahen, Claude, "Un traite d'armurerie compose pour Saladin". Bulletin d'etudes orientales 12 [1947–1948]:103–163.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catapults. |

- Res Gestae, 4th century, by Ammianus Marcellinus

- Medieval Mechanical Artillery, by the Xenophon Group

- Onager Physics. An analysis of the Onager/Mangonel

- Mangonel Animation