Economics is an influential introductory textbook by American economists Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus first published in 1948.

8nd ed. (1970)

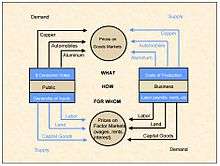

- The competitive price system uses supply-demand markets to solve the trio of economic problems — What How, and For Whom All demand relations are shown in blue. all the supply relations, in black.

- p. 41

- How do we measure the net national product, NNP? The general idea is simple. Figure 10-1 shows the circular flow of dollar spending in an economy with no government and no accumulation of capital or net saving going on.

- p. 170

- Unless proper macroeconomic policies are pursued, a laissez faire economy cannot guarantee that there will be exactly the required amount of investment to ensure full employment: not too little so as to cause unemployment, nor too much so as to cause inflation. As far as total investment. ..is concemed, the laissez faire system is without a good thermostat.

- p. 195

- Where the stimulus to investment is concerned, the system is somewhat in the lap of the Gods. We may be lucky or unlucky; and one of the few things you can say about luck is, "It's going to change." Fortunately, things need not be left to luck. We shall see that perfectly sensible public and private policies can be followed that have greatly enhanced the stability and productive growth of the mixed economy.

- p. 196

- Figure 12-6 pulls together in a simplified way the main elements of income determination. Without saving and investment, there would be a circular flow of income between business and the public: above, business pays out wages, interest, rents, and profits to the public in return for the services of labor and property; and below, the public pays consumption dollars to business in return for goods and services.

Realistically, we must recognize that the public will wish to save some of its income, as shown at the spigot Z. Hence, businesses cannot expect their consumption sales to be as large as the total of wages, interest, rents, and profits.- p. 218

- An increased desire to consume — which is another way of looking at a decreased desire to save — is likely to boost business sales and increase investment. On the other hand, a decreased desire to consume — i.e., an increase thriftness — is likely to reduce inflationary pressure in times of booming incomes; but in time of depression, it could make the depression worse and reduce the amount of actual net capital formation in the community. High consumption and high investment are then hand in hand rather than opposed to each other.

- p. 224

- What good does it do a black youth to know that an employer must pay him $2 an hour if the fact that he must be paid that amount is what keeps him from getting a job?

- p. 372

15th ed. (1995)

Thoughts on the Forty-sixth Birthday of a classic Economics Textbook

- Linus Pauling, so great a scholar and humanist that he was to win two Nobel Prizes, had already written a leading chemistry text—just as the great Richard Feynman was later to publish classic physics lectures. William James had long since published his great Principles of Psychology. Richard Courant, top dog at Gottingen in Germany, had not been to proud to author an accurate textbook on calculus. Who was Paul Samuelson to throw stones at scholars like these? And, working the other side of the street, I thought it was high time that we got the leaders in economics back in the trenches of general education.

- p. xxvi

- Starting a baby is easy. Bringing it to full term involves labor and travail.

- p. xxvi

- Economics is not merely a game, not merely a neat puzzle to test your powers of logic, arithmetic, and mathematical virtuosity.

- p. xxix

- In the long run the facts win out. The fanatical simplicities perish in the Darwinian struggle for survival of useful principle. To illustrate this, listen to what I used to say to one of my generation's leading economists (a warm friend with a strong ideology that differed considerably from my own eclectic value judgments and methodology):

You are a brilliant scholar, dazzlingly creative, with clear-cut economic convictions. But for you, things are either simply absurd or absurdly simple. Indeed the good fairies gave you every gift save one—the invaluable gift of "maybe."- p. xxix-xxx

16th ed. (1998)

A Golden Birthday

- History — at least economic history — has taught the world certain basic economic principles that have been learned and tested the hard way.

- p. xxiv

- A historian of mainstream-economic doctrines, like a paleontologist who studies the bones and fossils in different layers of earth, could date the ebb and flow of ideas by analyzing how Edition 1 was revised to Edition 2 and, eventually, to Edition 16.

- p. xxvi

- If it doesn’t make good sense, it isn't good economics.

- p. xxvii

Ch. 8 : The Behavior of Perfectly Competitive Markets

- We have seen that markets have remarkable efficiency properties. But we cannot say that laissez-faire capitalism produces the greatest happiness of the greatest numbers. Nor does it necessarily result in the fairest possible use of resources. Why not? Because people are not equally endowed with purchasing power. Some are very poor through no fault of their own, while others are very rich through no virtue of their own. So the weighting of dollar votes, which lie behind the individual demand curves, may look unfair. [...] A society does not live on efficiency alone. Philosophers and the populace ask, Efficiency for what? And for whom? A society may choose to change a laissez-faire equilibrium to improve the equity or fairness of the distribution of income and wealth. The society may decide to sacrifice efficiency to improve equity. [...] There are no correct answers here. These are normative questions that are answered in the political arena by democratic voters or autocratic planners. Positive economics cannot say what steps governments should take to improve equity. But economics can offer some insights into the efficiency of different government policies that affect the distribution of income and consumption.

- "Two Cheers for the Market, but Not Three", p. 151

Ch. 30 : Ensuring Price Stability

- Until the 1970s, high inflation usually went hand in hand with high employment and output.In the United States, inflation tended to increase when investment was brisk and jobs were plentiful. Periods of deflation or declining inflation [...] were times of high unemployment of labor and capital.

But a more careful examination of the historical record has revealed an interesting fact: The positive association between output and inflation appears to be only a temporary relationship. Over the longer run, there seems to be an inverse-U-shaped relationship between inflation and output growth.- p. 585

19th ed. (2010)

Ch. 1 : The Central Concepts of Economics

- Let us begin with a definition of economics. Over the last half-century, the study of economics has expanded to include a vast range of topics. Here are some of the major subjects that are covered in this book:

● Economics explores the behavior of the financial markets, including interest rates, exchange rates, and stock prices.

● The subject examines the reasons why some people or countries have high incomes while others are poor; it goes on to analyze ways that poverty can be reduced without harming the economy.

● It studies business cycles — the fluctuations in credit, unemployment, and inflation — along with policies to moderate them.

● Economics studies international trade and finance and the impacts of globalization, and it particularly examines the thorny issues involved in opening up borders to free trade.

● It asks how government policies can be used to pursue important such as rapid economic growth, efficient use of resources, full employment, price stability, and a fair distribution of income.This is a long list, but we could extend it many times. However, if we boil down all these definitions, we find one common theme:

Economics is the study of how societies use scarce resources to produce valuable goods and services and distribute them among different individuals

Ch. 5 : Demand and Consumer Behavior

- Utility is a scientific construct that economists use to understand how rational consumers make decisions.

Ch. 30 : Inflation

- Until the 1970s, high inflation in the United States usually went hand in hand with economic expansions; inflation tended to increase when investment was brisk and jobs were plentiful. Periods of deflation or declining inflation [...] were times of high unemployment of labour and capital.

Quotes about Economics

- The translation was terrible. It employed convoluted Hebrew terms for simple economic concepts. Nevertheless, I fell in love with the book’s content. What struck me most was the realization that one can in fact think systematically about complex social phenomena and describe them in precise language. All this was new to me, and my fascination grew with every page.

- Elhanan Helpman, “Doing Research.” (1998) In Passion and Craft. edited by Michael Szenberg

- One of the things Robin Wells and I did when writing our principles of economics textbook was to acquire and study a copy of the original, 1948 edition of Samuelson’s textbook. It’s an extraordinary work: lucid, accessible without being condescending, and deeply insightful. His discussions of speculation and monetary policy are particularly striking: they run quite contrary to much of what was being taught just a few years ago, but they ring completely true in the current crisis. And he was, of course, the man who truly brought Keynesian economics to America — a contribution that now seems more relevant than ever.

- Paul Krugman, "Paul Samuelson, R.I.P." (December 13, 2009)

- What sex is to the biology classroom, stocks and investment riskiness is to the sophomore economics lecture hall. That chapter on personal finance, put there to keep hard-boiled MIT electrical engineers awake, helped make introductory economics the largest elective course at hundreds of colleges. My great predecessors—John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, Frank Taussig and Irving Fisher—were writing for their times. I was writing for the last half of the 20th century-an epoch that surpassed even my youthful optimism. Those classic authors had dealt with essentially pure capitalism. I had to grapple with the tradeoffs and opportunities inherent in the mixed economy, a social pattern that by now spreads across the continents of the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

- Paul Samuelson, "Samuelson's Economics at Fifty: Remarks on the Occasion of the Anniversary of Publication", The Journal of Economic Education, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Autumn, 1999)

- Samuelson's textbook has delivered a great deal of economic wisdom. For many economists, the positive side of the balance sheet has outweighed the negative. Indeed, his defenders might ask: Might the United States and the West have suffered another Great Depression if Samuelson had not emphasized the need for "automatic stabilizers"? Did not Samuelson's heralding of the "mixed" economy curb the appetite of third world countries for national socialism?

We will never know, of course, but it is humbling to speculate on whether alterations in principles textbooks might have led to a different U.S. economy.- Mark Skousen, "The Perseverance of Paul Samuelson's Economics", The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Spring, 1997)