Paul Samuelson

Paul Anthony Samuelson (May 15, 1915 – December 13, 2009) was an American economist. He was the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Quotes

1940s

Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947; 1983)

- Science is not art. Yet, despite the lack of complete identity between art and science, there is much in common among different creative processes.

- Introduction to the Enlarged Edition

- Just as Hegel is said to have understood his philosophy for the first time when he read its French translation, Vilfredo Pareto could have learned what it was he meant exactly to say when he read Bergson's 1938 classic.

- Introduction to the Enlarged Edition

- I was lucky to enter economics in 1932. Analytical economics was poised for its take-off. I faced a lovely vacuum that young economists today can hardly imagine. So much remained to be done. Everything was still in an imperfect state. It was like fishing in a virgin lake: a whopper at every cast, but so many lovely new specimens that the palate never cloyed.

- Introduction to the Enlarged Edition

- The existence of analogies between central features of various theories implies the existence of a general theory which underlies the particular theories and unifies them with respect to those central features. This fundamental principle of generalization by abstraction was enunicated by the eminent American mathematician E. H. Moore more than thirty years ago. It is the purpose of the pages that follow to work out its implication for theoretical and applied economics.

- Ch. 1 : Introduction

- The general method involved may be very simply stated. In cases where the equilibrium values of our variables can be regarded as the solutions of an extremum (maximum or minimum) problem, it is often possible regardless of the number of variables involved to determine unambiguously the qualitative behavior of our solution values in respect to changes of parameters.

- Ch. 2 : The Theory of Maximizing Behavior

- In the preface to the reissue of Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Frank Knight makes the penetrating observation that under the conditions envisaged above the velocity of circulation would become infinite and so would the price level. This is perhaps an over-dramatic way of saying that nobody would hold money, and it would become a free good to go into the category of shell and other things which once served as money. We should expect too that it would not only pass out of circulation, but it would cease to be used as a conventional numeraire in terms of which prices are expressed. Interest bearing money would emerge. Of course, the above does not happen in real life, precisely because uncertainty, contingency needs, non-synchronization of revenues and outlay, transaction frictions, etc., etc., all are with us. But the abstract special case analyzed above should warn us against the facile assumption that the average levels of the structure of interest rates are determined solely or primarily by these differential factors. At times they are primary, and at other times, such as the twenties in this country, they may not be. As a generalization I should hazard the hypothesis that they are likely to be of great importance in an economy in which there is a “quasi-zero" rate of interest. I think by this hypothesis one can explain many of the anomalies of the United States money market in the thirties.

- Ch. 5 : Theory of Consumer’s Behavior

Economics (1948-)

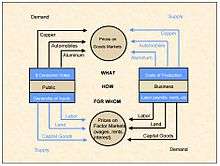

The competitive price system adapted from Samuelson, 1961

- Figure 12-6 pulls together in a simplified way the main elements of income determination. Without saving and investment, there would be a circular flow of income between business and the public: above, business pays out wages, interest, rents, and profits to the public in return for the services of labor and property; and below, the public pays consumption dollars to business in return for goods and services.

Realistically, we must recognize that the public will wish to save some of its income, as shown at the spigot Z. Hence, businesses cannot expect their consumption sales to be as large as the total of wages, interest, rents, and profits.- 8th ed., 1970, p. 218

1950s–1970s

- Econometrics may be defined as the quantitative analysis of actual economic phenomena based on the concurrent development of theory and observation, related by appropriate methods of inference.

- Paul Samuelson, Tjalling Koopmans, and Richard Stone. "Report of the evaluative committee for Econometrica." Econometrica- journal of the Econometric Society. (1954): 141-146.

- The stock market has forecast nine of the last five recessions.

- Paul Samuelson (1966), quoted in: John C Bluedorn et al. Do Asset Price Drops Foreshadow Recessions? (2013), p. 4

- I used to joke to Bob Solow that the distance between me and Joan Robinson is less than the distance between Joan Robinson and me. His reply was, “You’ll never convince her of that.” Still one lives in hope.

- On April 14, 1972, quoted in Marjorie Shepherd Turner, Joan Robinson and the Americans (1989)

Maximum Principles in Analytical Economics, 1970

"Maximum Principles in Analytical Economics," Prize Lecture, Lecture to the memory of Alfred Nobel, December 11, 1970

- The very name of my subject, economics, suggests economizing or maximizing. But Political Economy has gone a long way beyond home economics. Indeed, it is only in the last third of the century, within my own lifetime as a scholar, that economic theory has had many pretensions to being itself useful to the practical businessman or bureaucrat. I seem to recall that a great economist of the last generation, A. C. Pigou of Cambridge University, once asked the rhetorical question, “Who would ever think of employing an economist to run a brewery?” Well, today, under the guise of operational research and managerial economics, the fanciest of our economic tools are being utilized in enterprises both public and private.

- p. 62: Lead paragraph

- With the assistance of mathematics, I can see a property of the ninety-nine dimensional surfaces hidden from the naked eye. If an increase in the price of fertilizer alone always increases the amount the firm buys of caviar, from that fact alone I can predict the answer to the following experiment which I have never seen performed and upon which I have no observations: an increase in the price of caviar alone will increase the amount the firm buys of fertilizer. In thermodynamics such reciprocity or integrability conditions are known as Maxwell Conditions; in economics they are known as Hotelling conditions in honor of Harold Hotelling’s 1932 work.

- p. 67

- There is really nothing more pathetic than to have an economist or a retired engineer try to force analogies between the concepts of physics and the concepts of economics. How many dreary papers have I had to referee in which the author is looking for something that corresponds to entropy or to one or another form of energy. Nonsensical laws, such as the law of conservation of purchasing power, represent spurious social science imitations of the important physical law of the conservation of energy; and when an economist makes reference to a Heisenberg Principle of indeterminacy in the social world, at best this must be regarded as a figure of speech or a play on words, rather than a valid application of the relations of quantum mechanics.

- p. 69

- An American economist of two generations ago, H. J. Davenport, who was the best friend Thorstein Veblen ever had (Veblen actually lived for a time in Davenport’s coal cellar) once said: “There is no reason why theoretical economics should be a monopoly of the reactionaries.” All my life I have tried to take this warning to heart, and I dare call it to your favorable attention.

- p. 76

1980s–1990s

- After 1929 it was the sturdy middle classes, and not just the lumpen proletariat, who were down and out. It was not all that unfashionable or disreputable to be bankrupt. By the last Hoover years, the states and localities had run out of money for relief. In middle-class neighborhoods like mine, you constantly had children at the door, asking by mouth or with a note for a dime, a quarter, or a potato: saying, in a believable fashion, we are starving.

- Samuelson (1985; p, 6) as cited in: Klein, Daniel B., and Ryan Daza. "Paul A. Samuelson (Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates)." Econ Journal Watch 10.3 (2013): 561-569.

- The recent market run-up that appreciated run-of-the- mill shares also chanced to send up those token gold holdings. Pure luck, undeserved and unlikely to reoccur. Good questions outrank easy answers.

- In: Paul Anthony Samuelson, Kate Crowley (1986), The Collected Scientific Papers, Volume 5, p. 561

- I can claim that in talking about modern economics I am talking about me. My finger has been in every pie. I once claimed to be the last generalist in economics, writing about and teaching such diverse subjects as international trade and econometrics, economic theory and business cycles, demography and labor economics, finance and monopolistic competition, history of doctrines and locational economics.

- February 1985, in William Breit and Roger W. Spencer (ed.) Lives of the laureates

- I reproach myself for a gross error. But I would reproach myself more if I had persisted in an error after observations revealed it clearly to be that. I made a deal of money in the late 1940s on the bull side, ignoring Satchel Paige’s advice to Lot’s wife, “Never look back.” Rather I would advocate Samuelson’s Law: “Always look back. You may learn something from your residuals. Usually one’s forecasts are not so good as one remembers them; the difference may be instructive.” The dictum “If you must forecast, forecast often,” is neither a joke nor a confession of impotence. It is a recognition of the primacy of brute fact over pretty theory. That part of the future that cannot be related to the present’s past is precisely what science cannot hope to capture. Fortunately, there is plenty of work for science to do, plenty of scientific tasks not yet done.

- February 1985, in William Breit and Roger W. Spencer (ed.) Lives of the laureates

- My mind is ever toying with economic ideas and relationships. Great novelists and poets have reported occasional abandonment by their muse. The well runs dry, permanently or on occasion. Mine has been a better luck. As I have written elsewhere, there is a vast inventory of topics and problems floating in the back of my mind. More perhaps than I shall ever have occasion to write up for publication. A result that I notice in statistical mechanics may someday help resolve a problem in finance.

- February 1985, in William Breit and Roger W. Spencer (ed.) Lives of the laureates

- As a theorist I have great advantages. All I need is a pencil (now a ball pen) and an empty pad of paper. There are analysts who sit and look vacantly out the window, but after the age of 20 I was not one of them. I ought to envy the new generation who have grown up with the computer, but I don’t. None of them known to me sits idly at the console, improvising and experimenting in the way that a composer does at the piano. That ought to become increasingly possible. But up to now, in my observation, the computer is largely a black box into which researchers feed raw input and out of from which they draw various summarizing measures and simulations. Not having access to look around in the box, the investigator has less intuitive familiarity with the data than used to be the case in the bad old days.

- “My Life Philosophy: Policy Credos and Working Ways,” in M. Szenberg (ed.) Eminent Economists: Their Life Philosophies (1992)

- It is some relief to move from the exalted realm of philosophical ethics to the mundane realm of scientific methodology. However, I rather shy away from discussions of Methodology with a capital M. To paraphrase Shaw: Those who can do science; those who can’t prattle about its methodology.

- “My Life Philosophy: Policy Credos and Working Ways,” in M. Szenberg (ed.) Eminent Economists: Their Life Philosophies (1992)

- What sex is to the biology classroom, stocks and investment riskiness is to the sophomore economics lecture hall.

- Samuelson's Economics at Fifty: Remarks on the Occasion of the Anniversary of Publication (1998)

- I tell no secret when I repeat that fame and reputation are much a matter of luck and chance.

- Samuelson's Economics at Fifty: Remarks on the Occasion of the Anniversary of Publication (1998)

New millennium

- Economics never was a dismal science. It should be a realistic science.

- Samuelson, Paul Anthony; Puttaswamaiah, K. (2002). Paul Samuelson and the Foundations of Modern Economics. p. 10.

- Modigliani's theory was a powerful searchlight on what was happening... It is the best explanation of what has actually been happening in the great swing of American life since the 1950's.

- Paul Samuelson in: Louis Uchitelle. "Franco Modigliani, 85, Nobel-Winning Economist, Dies" in New York Times, September 26, 2003.

- An evolving discipline–whether it be history or economics or astrophysics or immunology–is ever dynamically changing. Two steps forward and X steps back, so to speak. Periodically, the scholarly group registers more or less self-confidence, self-esteem, and complacency. We careerists are happiest when recent past achievements have seemed to be successful, but when still there are completable tasks dimly visible ahead.

- "Foreword: Eavesdropping on the Future?" in New Frontiers in Economics (2004)

- Here is my advice. When in doubt, give my new efforts a hearing. Many feel a calling to break new ground; in the end, few will end upfinding their efforts chosen. But the yea-sayer does do less harm than the naysayer, in that the Darwinian process of adverse testing will in time (most likely?) separate the useful from the useless, the trivial from the profound.

- "Foreword: Eavesdropping on the Future?" in New Frontiers in Economics (2004)

- I had a great admiration for Pigou. I thought that, in many ways, he was not only a faithful follower of Alfred Marshall, but he was also a more fertile developer of the Marshallian tradition than Marshall himself. … Whitehead said to me:“Don’t you think that Pigou was an overrated economist? Wasn’t Foxwell a better man?” Since I am an honest man, I said to Whitehead:“No, I think Pigou was a much more important economist than Foxwell.”

- Kotaro Suzumura, An interview with Paul Samuelson: welfare economics,“old” and “new”, and social choice theory (2005)

- I think Marshall was a great economist, but he was a potentially much greater economist than he actually was. It was not that he was lazy, but his health was not good, and he worked in miniature.

- Kotaro Suzumura, An interview with Paul Samuelson: welfare economics,“old” and “new”, and social choice theory (2005)

- Arrow’s general impossibility theorem does not disprove the existence of the Bergsonian social welfare function, neither does it disprove the existence of the Benthamite hedonistic function.

- Kotaro Suzumura, An interview with Paul Samuelson: welfare economics,“old” and “new”, and social choice theory (2005)

- I return to economics and to economists, and to the question of why the profession’s directions have evolved in the manners evident from this book. A major conservative economist once explained that a source of his antipathy to government traced back to the defeat of his southern ancestors by a larger north economy. Here is a similar factoid. Joan Robinson once wrote that her opposition to having the U.K. enter the European Market was due to the fact that she “had more friends in [Nehru’s] India than on the continent.”

- Coeditor's Forword in Inside the economist’s mind: conversations with eminent economists (2007)

- We economists love to quote Keynes’s final lines in his 1936 General Theory—for the reason that they cater so well to our vanity and self-importance. But to admit the truth, madmen in authority can self generate their own frenzies without needing help from either defunct or avant-garde economists. What establishment economists brew up is as often what the Prince and the Public are already wanting to imbibe. We guys don’t stay in the best club by proffering the views of some past academic crank or academic sage.

- Coeditor's Forword in Inside the economist’s mind: conversations with eminent economists (2007)

- What then is it that, since 2007, has caused Wall Street capitalism's own suicide? At the bottom of this worst financial mess in a century is this: Milton Friedman-Friedrich Hayek libertarian laissez-faire capitalism, permitted to run wild without regulation. This is the root source of today's travails. Both of these men are dead, but their poisoned legacies live on.

- "Farewell to Friedman-Hayek Libertarian Capitalism", Tribune Media Services (2008)

- Scholars still debate whether Columbus brought syphilis to the New World or vice versa. But it cannot be doubted that the 2008 world meltdown carries on its label the words Made in America.

- "Farewell to Friedman-Hayek Libertarian Capitalism", Tribune Media Services (2008)

- Well, I will say this. And this is the main thing to remember. Macroeconomics -- even with all of our computers and with all of our information -- is not an exact science and is incapable of being an exact science. It can be better or it can be worse, but there isn't guaranteed predictability in these matters.

- Conor Clarke, An Interview With Paul Samuelson, Part One (2009)

- Well, I'd say, and this is probably a change from what I would have said when I was younger: Have a very healthy respect for the study of economic history, because that's the raw material out of which any of your conjectures or testings will come. And I think the recent period has illustrated that. The governor of the Bank of England seems to have forgotten or not known that there was no bank insurance in England, so when Northern Rock got a run, he was surprised. Well, he shouldn't have been.

But history doesn't tell its own story. You've got to bring to it all the statistical testings that are possible. And we have a lot more information now than we used to.- Conor Clarke, An Interview With Paul Samuelson, Part Two (2009)

- Globalization presumes sustained economic growth. Otherwise, the process loses its economic benefits and political support.

- Quoted in: Richard Duncan (2011) The Dollar Crisis, p. 232

An Interview with Paul A. Samuelson, 2003

William A. Barnett, An Interview with Paul A. Samuelson (December 23, 2003)

- The proof of the pudding is in the eating. There was a widespread myth of the 1970s, a myth along Tom Kuhn’s (1962) Structure of Scientific Revolutions lines. The Keynesianism, which worked so well in Camelot and brought forth a long epoch of price-level stability with good Q growth and nearly full employment, gave way to a new and quite different macro view after 1966. A new paradigm, monistic monetarism, so the tale narrates, gave a better fit. And therefore King Keynes lost self esteem and public esteem. The King is dead. Long live King Milton!

Contemplate the true facts. Examine 10 prominent best forecasting models 1950 to 1980: Wharton, Townsend–Greenspan, Michigan Model, St. Louis Reserve Bank, Citibank Economic Department under Walter Wriston’s choice of Lief Olson, et cetera. … M did matter as for almost everyone. But never did M alone matter systemically, as post-1950 Friedman monetarism professed.

- A later writer, such as Leijonhufvud, I knew to have it wrong, when he later argued the merits of Keynes’s subtle intuitions and downplayed the various (identical!) mathematical versions of The General Theory. The so-called 1937 Hicks or later Hicks–Hansen IS–LM diagram will do as an example for the debate.

- I would guess that most MIT Ph.D.’s since 1980 might deem themselves not to be “Keynesians.” But they, and modern economists everywhere, do use models like those of Samuelson, Modigliani, Solow, and Tobin. Professor Martin Feldstein, my Harvard neighbor, complained at the 350th Anniversary of Harvard that Keynesians had tried to poison his sophomore mind against saving. Tobin and I on the same panel took this amiss, since both of us since 1955 had been favoring a “neoclassical synthesis,” in which full employment with an austere fiscal budget would add to capital formation in preparation for a coming demographic turnaround.

- Often I’ve stated how I hate to be wrong. That has aborted many a tempting error, but not all of them. But I hate much more to stay wrong. Early on, I’ve learned to check back on earlier proclamations. One can learn much from one’s own errors and precious little from one’s triumphs. By September of 1945, it was becoming obvious that oversaving was not going to cause a deep and lasting post-war recession. So then and there, I cut my losses on that bad earlier estimate.

- My notion of a fruitful economic science would be that it can help us explain and understand the course of actual economic history. A scholar who seriously addresses commentary on contemporary monthly and yearly events is, in this view, practicing the study of history—history in its most contemporary time phasing.

An Enjoyable Life Puzzling Over Modern Finance Theory, 2009

"An Enjoyable Life Puzzling Over Modern Finance Theory", Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2009. 1:19–35

- When I once called myself a “Sunday painter” dabbling in stochastic finance, that was not meant to belittle finance theory as a branch of serious economic theory. Such a peculiar view was expressed again and again by the late Milton Friedman, a dizzy view that I still find incomprehensible.

- From the beginning I could not believe that the “efficient market” hypothesis was dependent on a pure Brownian motion white noise or any truly random random walk. Place a minuscule colloidal molecule on a horizontal table that covers unlimited acres. Bombard it from every direction with thousands of minute atoms; and then if you wait long enough that original molecule can have traveled a billion miles in one direction. That’s truly a random Bachelier-Einstein walk, but not my notion of economic fluctuations.

- Moral: To understand economics you need to know not only fundamentals but also its nuances. Darwin is in the nuances. When someone preaches “Economics in one lesson,” I advise: Go back for the second lesson.

- Moral: free markets do not stabilize themselves. Zero regulating is vastly suboptimal to rational regulating. Libertarianism is its own worst enemy!

- Markets are not perfect, which is true even for rationally regulated markets. Nevertheless, over the last thousand years every attempt to organize sizeable societies without important dependence on markets has generated its own failure ...

Quotes about Paul Samuelson

- Paul Samuelson is omnipresent in American and even world economics; like Joyce's Humphrey Chimpeden Earwicker or Melville's Confidence Man,. he appears at every turn of history and in every disguise.

- Kenneth J. Arrow, "Samuelson Collected", Journal of Political Economy Vol. 75, No. 5 (Oct., 1967), pp. 730-737

- Paul’s work combined breadth and intensity. On the one hand, his structures were grounded in a very wide knowledge of the nature of mathematical systems used to describe natural phenomena. On the other, he studied individual questions in economics, sometimes at a very detailed level.

- Kenneth J. Arrow, Foreword in Samuelsonian economics and the twenty-first century edited by Michael Szenberg, Lall Ramrattan, Aron A.. Gottesman (2006)

- As an intellectual and economist, there were two Samuelsons. There was the mathematical savant who had learned his trade at the feet of Viner, Leontief, Schumpeter and, above all, Wilson. This work had raised him above most of his contemporaries, enabling him to speak with the authority of one of the leading economists of his generation. However, his more popular work was not just a distillation of his abstract theories; it rested not on complex mathematical arguments but involved careful data analysis and familiarity with the way that economic institutions worked. This was the Samuelson, mentored by Hansen during the Second World War, who wrote Economics and whose views were sought by the press and government.

- Roger Backhouse, "The people’s economist" (10 February, 2020)

- I got to know Paul Samuelson well during 2001-02 when I was a visiting professor at MIT. I would pause every now and then at his office to chit-chat about things. He was into his grey years by then and seemed a bit lonely. His interests were voracious — from the intricacies of science to the lives of people and he liked to chat.

My last proper conversation with him was on May 15, 2002. I was photocopying something at MIT, when he stopped and said that it was his birthday that day. The Harvard Club would open a special champagne for him and he asked me if my wife and I would come to the Harvard Club. For an economist, that’s the equivalent of Einstein asking a physicist to dinner. I, of course, said yes, expecting lots of people there. It turned out to be a dinner with Samuelson, his charming wife Richa and the two of us. It was one of the most memorable evenings of my life. We — truth be told, mainly he —talked about art, history and, of course, economics.- Kaushik Basu, "He left his imprint on every field of economics" (Dec 14, 2009)

- The readers of this space know Paul Samuelson as a witty, informed and often acerbic commentator on current affairs, as a “liberal” supporter of the economic policies of the Kennedy and Johnson years, and as a critic of current Nixon economic policy.

Millions of college graduates know Paul Samuelson for his economics textbook, which has been the leading elementary text in the United States for two decades, has sold nearly 3 million copies, and is almost surely the best-selling book on economics ever published in the Western world.

Professional economists know Paul Samuelson as a mathematical economist who has ranged widely and deeply, who has helped to reshape and improve the theoretical foundations of our subject. This is the work for which this remarkably versatile man won the Nobel Prize. In the words of the announcement, the prize was awarded “for the scientific work through which he has developed static and dynamic economic theory and actively contributed to raising the level of analysis in economic science.”- Milton Friedman, "Paul Samuelson", Newsweek (9 November 1970)

- Another big influence was Samuelson's Foundations, which I read when I stated here at Chicago. It's a "how-to-do-it" book. a great book for first-year graduate students. It says, "Here's the way you do it." It lets you in on the secret of how you play the game, as opposed to cutting you off with big words. I think the combination of Samuelson's book plays Friedman's class was what got me going.

- Robert E. Lucas, in Conversations with Economists (1983) by Arjo Klamer

- The only way I feel I understand something is if I can write it down in a model and make it work. I felt that from the beginning. That's why I liked Samuelson's book. He'll take these incomprehensible verbal debates that go on and on and never end and just end them; formulate the issue in such a way that the question is answerable, and then get the answer.

- Robert E. Lucas, in Conversations with Economists (1983) by Arjo Klamer

- Samuelson says I was wrong and he was right, and he froths at the mouth when people talk about the lighthouse example. He says Coase is wrong; he doesn't overcome the free rider problem. Who are the free riders? The foreign ships going past the British coast which do not call at a British port. Using Samuelson's approach, what do you do? Do you ask the foreign governments to give you a subsidy? Do you tax people in Britain because the foreign ships are getting help without paying for it? What do you do?

My approach is to compare the alternatives. People like Samuelson like to set up a perfect world and say that the market does not bring us to this point and imply that the government should do something. They stop their analysis at that point.- Ronald Coase, in "Looking For Results" (1997)

- Between meals I arranged a light, informal trivia competition. Had answers been counted, he would have won hands down. He even knew the third president—of Finland—a question I threw in as a joke.

- Bengt Holmstrom, quoted in Michael Szenberg, Lall Ramrattan and Aron Gottesman, "Ten Ways to Know Paul A. Samuelson" (2006)

- Generally speaking, Samuelson's contribution has been that, more than any other contemporary economist, he has contributed to raising the general analytical and methodological level in economic science. He has in fact simply rewritten considerable parts of economic theory. He has also shown the fundamental unity of both the problems and analytical techniques in economics, partly by a systematic application of the methodology of maximization for a broad set of problems. This means that Samuelson's contributions range over a large number of different fields.

- Award Ceremony Speech 1970 at nobelprize.org, by Professor Assar Lindbeck, Stockholm School of Economics.

- Of course, one can go back to high school or, in my case, junior college and find roots; there are some indeed, but my professional beginnings were in the Berkeley that existed just before World War II and the scholarship I won to MIT. There I met the dazzling wunderkind Paul Samuelson. When I was browsing in the Berkeley library and came across early issues of Econometrica, Samuelson’s contributions caught my eye. When I got an opportunity to go to MIT, it was the possibility of working with Samuelson that confirmed all my choices. I was attached to him as a graduate assistant from the outset, and I tried to maximize my contact with him, picking up insights that he scattered on every encounter.

Working with Samuelson, who was at the forefront of interpreting Keynesian theory for teaching and policy application, I was put immediately in the midst of two challenging contests—one to gain acceptance for a way of thinking about macroeconomics and another to gain acceptance for a methodology in economics, namely, the mathematical method. Later, both challenges were to be overcome, but for ten or twenty years opposition was fierce.

Once Samuelson’s Economics became a widely used text in first courses in the subject, Keynesian economics was firmly embedded. There was no turning back from that achievement. The successive student generations turned more toward the mathematical approach in graduate school, and they taught or did research in this vein. That eventually established the mathematical method, first in the United States, then in Europe, Japan, India, and other centers. Much of the foundation was built in Europe, and many of the American masters at mathematical economics were immigrants, but Samuelson, Friedman, and others gave it a native-born American flavor, and the approach truly caught on in this country.- Lawrence R. Klein, Lecture at Trinity University in October 1984, published in Lives of the Laureates (5th ed., 2009), edited by William Breit and Barry T. Hirsh,

- He knows history. If he had a Hungarian sitting at his side at the dinner table, he would quote easily names of politicians or novelists of the Austrian–Hungarian empire of the late 19th century. He also understands the significance of the history of a country. This is a rare quality at a time when the education of economists has become excessively technical.

- János Kornai, quoted in Michael Szenberg, Lall Ramrattan and Aron Gottesman, "Ten Ways to Know Paul A. Samuelson" (2006)

- [Paul] mentioned that he had heard about a piece I had written on Irving Fisher. I have no idea how he heard about it, but I offered to send him a copy and within a few days I got back a letter. [Paul] read the paper and wanted to set down his own interpretation, but then he closes the letter with a remarkable line that I treasure: ‘Do disregard my heresies and follow your own star.’

- Perry Mehrling, quoted in Michael Szenberg, Lall Ramrattan and Aron Gottesman, "Ten Ways to Know Paul A. Samuelson" (2006)

- Samuelson is an artist; he brought undergraduates pretty well up to the level of the state of knowledge in the profession.

- Edward C. Prescott, interview in Brian Snowdon and Howard R. Vane. Modern macroeconomics: its origins, development and current state. (2005)

- There have been hedgehogs; there have been foxes; and then there was Paul Samuelson. (...) I’m referring, of course, to Isaiah Berlin’s famous distinction among thinkers – foxes who know many things, and hedgehogs who know one big thing. What distinguished Paul Samuelson as an economic thinker, making him like nobody else, past or present, was the fact that he knew – and taught us – many big things. No economist has ever had so many seminal ideas.

- One recent history of economic thought (Jürg Niehans’s A History of Economic Theory) devotes twenty-four pages to Samuelson’s ideas. Adam Smith only gets thirteen. Samuelson’s work on stock markets and the random walk takes up less than two of those twenty-four pages. He was “the last generalist in economics,” as he liked to say, and for him financial market studies were just a side project that he at times seemed deeply ambivalent about. His intervention was, however, crucial to the triumph of the random walk. Here was one of the most important economists of all time, and he didn’t think the relationship between coin flips and the stock market was a dinner-speech triviality.

- Justin Fox, Myth of Rational Market (2009), Ch. 4 : A Random Walk from Paul Samuelson to Paul Samuelson

- A few years ago, I had the good fortune of running across a first edition of Paul's textbook (not the recent reprint of the original text, but an actual 1948 edition). It was a real find. I bought the volume in an online auction for, if my recollection is correct, $35. Talk about consumer surplus! I would have gladly paid many times that.

At the next Boston Fed meeting, I took the book along to get Paul to sign it. Below is the book's title page, along with Paul's gracious inscription.- Greg Mankiw, "Memories of Paul" (December 15, 2009)

- John Maynard Keynes may have had more influence on policy makers, Milton Friedman on citizens, Kenneth Arrow on economic theory, but Samuelson had more influence on the way economics is done today, and the purposes to which it is put, than any other economist of the twentieth century.

- David Warsh, "The Enormous Black Box" (2009)

- He was influential. He influenced students through his textbook, and he influenced the entire economics profession through his dissertation, published as "Foundations of Economic Analysis." Readers of this blog will tend to disapprove of his influence, in that it promoted Keynes and the use of mathematical modeling. Perhaps Milton Friedman was more influential on policy. But Samuelson was more influential on the internal dynamics of the economics profession. On that score, I would say that he was without peer in this century. […] Compared with later generations of economists, he was more nuanced in his thinking and not as capable a mathematician.

- Arnold Kling, Thoughts on the Late Paul Samuelson (2009)

- Many principles of economics were hidden in obscure verbiage of previous generations; he reformulated and extended them with crystal clarity in the language of mathematics.

- Avinash Dixit, "Paul Samuelson's Legacy" (2012)

Michael Szenberg, "Ten Ways to Know Paul A. Samuelson" (2006)

External links

- "Paul A. Samuelson (Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates)," by Daniel B. Klein, and Ryan Daza. Econ Journal Watch 10.3 (2013): 561-569.

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.