Stock market index

A stock index, or stock market index, is an index that measures a stock market, or a subset of the stock market, that helps investors compare current price levels with past prices to calculate market performance.[1] It is computed from the prices of selected stocks (typically a weighted arithmetic mean).

Two of the primary criteria of an index are that it is investable and transparent:[2] The method of its construction are specified. Investors can invest in a stock market index by buying an index fund, which are structured as either a mutual fund or an exchange-traded fund, and "track" an index. The difference between an index fund's performance and the index, if any, is called tracking error. For a list of major stock market indices, see List of stock market indices.

Types of indices

Stock market indices may be classified in many ways. A 'world' or 'global' stock market index — such as the MSCI World or the S&P Global 100 — includes stocks from multiple regions. Regions may be defined geographically (e.g., Europe, Asia) or by levels of industrialization or income (e.g., Developed Markets, Frontier Markets).

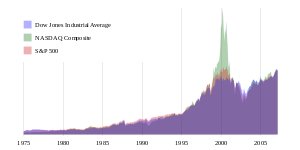

A 'national' index represents the performance of the stock market of a given nation—and by proxy, reflects investor sentiment on the state of its economy. The most regularly quoted market indices are national indices composed of the stocks of large companies listed on a nation's largest stock exchanges, such as the S&P 500 Index in the United States, the Nikkei 225 in Japan, the NIFTY 50 in India, and the FTSE 100 in the United Kingdom.

Many indices are regional, such as the FTSE Developed Europe Index or the FTSE Developed Asia Pacific Index. Indexes may be based on exchange, such as the NASDAQ-100 or groups of exchanges, such as the Euronext 100 or OMX Nordic 40.

The concept may be extended well beyond an exchange. The Wilshire 5000 Index, the original total market index, includes the stocks of nearly every public company in the United States, including all U.S. stocks traded on the New York Stock Exchange (but not ADRs or limited partnerships), NASDAQ and American Stock Exchange. The FTSE Global Equity Index Series includes over 16,000 companies.[3]

Indices exist that track the performance of specific sectors of the market. Some examples include the Wilshire US REIT Index which tracks more than 80 real estate investment trusts and the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index which consists of approximately 200 firms in the biotechnology industry. Other indices may track companies of a certain size, a certain type of management, or more specialized criteria such as in fundamentally based indexes.

Ethical stock market indices

Several indices are based on ethical investing, and include only companies that meet certain ecological or social criteria, such as the Calvert Social Index, Domini 400 Social Index, FTSE4Good Index, Dow Jones Sustainability Index, STOXX Global ESG Leaders Index, several Standard Ethics Aei indices, and the Wilderhill Clean Energy Index.[4]

In 2010, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation announced the initiation of a stock index that complies with Sharia's ban on alcohol, tobacco and gambling.[5]

Strict mechanical criteria for inclusion and exclusion exist to prevent market domination, such as in Canada when Nortel was permitted to rise to over 30% of the TSE 300 index value.

Ethical indices have a particular interest in mechanical criteria, seeking to avoid accusations of ideological bias in selection, and have pioneered techniques for inclusion and exclusion of stocks based on complex criteria.

Another means of mechanical selection is mark-to-future methods that exploit scenarios produced by multiple analysts weighted according to probability, to determine which stocks have become too risky to hold in the index of concern.

Critics of such initiatives argue that many firms satisfy mechanical "ethical criteria", e.g. regarding board composition or hiring practices, but fail to perform ethically with respect to shareholders, e.g. Enron. Indeed, the seeming "seal of approval" of an ethical index may put investors more at ease, enabling scams. One response to these criticisms is that trust in the corporate management, index criteria, fund or index manager, and securities regulator, can never be replaced by mechanical means, so "market transparency" and "disclosure" are the only long-term-effective paths to fair markets. From a financial perspective, it is not obvious whether ethical indices or ethical funds will out-perform their more conventional counterparts. Theory might suggest that returns would be lower since the investible universe is artificially reduced and with it portfolio efficiency. On the other hand, companies with good social performances might be better run, have more committed workers and customers, and be less likely to suffer reputation damage from incidents (oil spillages, industrial tribunals, etc.) and this might result in lower share price volatility.[6] The empirical evidence on the performance of ethical funds and of ethical firms versus their mainstream comparators is very mixed for both stock[7][8] and debt markets.[9]

Presentation of index returns

Some indices, such as the S&P 500 Index, have returns shown calculated with different methods.[10] These versions can differ based on how the index components are weighted and on how dividends are accounted. For example, there are three versions of the S&P 500 Index: price return, which only considers the price of the components, total return, which accounts for dividend reinvestment, and net total return, which accounts for dividend reinvestment after the deduction of a withholding tax.[11]

The Wilshire 4500 and Wilshire 5000 indices have five versions each: full capitalization total return, full capitalization price, float-adjusted total return, float-adjusted price, and equal weight. The difference between the full capitalization, float-adjusted, and equal weight versions is in how index components are weighted.[12][13]

Weighting of stocks within an index

An index may also be classified according to the method used to determine its price. In a price-weighted index such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average, NYSE Arca Major Market Index, and the NYSE Arca Tech 100 Index, the share price of each component stock is the only consideration when determining the value of the index. Thus, price movement of even a single security will heavily influence the value of the index even though the dollar shift is less significant in a relatively highly valued issue, and moreover ignoring the relative size of the company as a whole. In contrast, a Capitalization-weighted index (also called market-value-weighted) such as the S&P 500 Index or Hang Seng Index factors in the size of the company. Thus, a relatively small shift in the price of a large company will heavily influence the value of the index.

Capitalization- or share-weighted indices have a full weighting, i.e. all outstanding shares were included. Many indices are based on a free float-adjusted weighting.

An equal-weighted index is one in which all components are assigned the same value.[14] For example, the Barron's 400 Index assigns an equal value of 0.25% to each of the 400 stocks included in the index, which together add up to the 100% whole.[15]

A modified capitalization-weighted index is a hybrid between capitalization weighting and equal weighting. It is similar to a capitalization weighting with one main difference: the largest stocks are capped to a percent of the weight of the total stock index and the excess weight will be redistributed equally amongst the stocks under that cap. In 2005, Standard & Poor's introduced the S&P Pure Growth Style Index and S&P Pure Value Style Index which was attribute-weighted. That is, a stock's weight in the index is decided by the score it gets relative to the value attributes that define the criteria of a specific index, the same measure used to select the stocks in the first place. For these two indexes, a score is calculated for every stock, be it their growth score or the value score (a stock cannot be both) and accordingly they are weighted for the index.[16]

Criticism of capitalization-weighting

One argument for capitalization weighting is that investors must, in aggregate, hold a capitalization-weighted portfolio anyway. This then gives the average return for all investors; if some investors do worse, other investors must do better (excluding costs).[17]

Investors use theories such as modern portfolio theory to determine allocations. This considers risk and return and does not consider weights relative to the entire market. This may result in overweighting assets such as value or small-cap stocks, if they are believed to have a better return for risk profile. These investors believe that they can get a better result because other investors are not very good. The capital asset pricing model says that all investors are highly intelligent, and it is impossible to do better than the market portfolio, the capitalization-weighted portfolio of all assets. However, empirical tests conclude that market indices are not efficient. This can be explained by the fact that these indices do not include all assets or by the fact that the theory does not hold. The practical conclusion is that using capitalization-weighted portfolios is not necessarily the optimal method.

As a consequence, capitalization-weighting has been subject to severe criticism (see e.g. Haugen and Baker 1991, Amenc, Goltz, and Le Sourd 2006, or Hsu 2006), pointing out that the mechanics of capitalization-weighting lead to trend following strategies that provide an inefficient risk-return trade-off.

Other stock market index weighting schemes

While capitalization-weighting is the standard in equity index construction, different weighting schemes exist. While most indices use capitalization-weighting, additional criteria are often taken into account, such as sales/revenue and net income, as in the Dow Jones Global Titan 50 Index.

As an answer to the critiques of capitalization-weighting, equity indices with different weighting schemes have emerged, such as "wealth"-weighted (Morris, 1996), Fundamentally based indexes (Robert D. Arnott, Hsu and Moore 2005), "diversity"-weighted (Fernholz, Garvy, and Hannon 1998) or equal-weighted indices.[18]

Indices and passive investment management

Passive management is an investing strategy involving investing in index funds, which are structured as mutual funds or exchange-traded funds that track market indices.[19] The SPIVA (S&P Indices vs. Active) annual "U.S. Scorecard", which measures the performance of indices versus actively managed mutual funds, finds the vast majority of active management mutual funds underperform their benchmarks, such as the S&P 500 Index, after fees.[20][21] Since index funds attempt to replicate the holdings of an index, they eliminate the need for — and thus many costs of — the research entailed in active management, and have a lower churn rate (the turnover of securities, which can result in transaction costs and capital gains taxes).

Unlike a mutual fund, which is priced daily, an exchange-traded fund is priced continuously, is optionable, and can be sold short.[22]

See also

- Index of accounting articles

- Index of economics articles

- Index of management articles

- List of stock exchanges

- List of stock market indices

- Outline of finance

- Outline of marketing

References

- Caplinger, Dan (January 18, 2020). "What Is a Stock Market Index?". The Motley Fool.

- Lo, Andrew W. (2016). "What Is an Index?". Journal of Portfolio Management. 42 (2): 21–36. doi:10.3905/jpm.2016.42.2.021.

- "FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS)". FTSE Russell.

- Divine, John (February 15, 2019). "7 of the Best Socially Responsible Funds". U.S. News & World Report.

- Haris, Anwar (November 25, 2010). "Muslim-Majority Nations Plan Stock Index to Spur Trade: Islamic Finance". Bloomberg L.P.

- Oikonomou, Ioannis; Brooks, Chris; Pavelin, Stephen (2012). "The impact of corporate social performance on financial risk and utility: a longitudinal analysis" (PDF). Financial Management. 41 (2): 483–515. doi:10.1111/j.1755-053X.2012.01190.x. ISSN 1755-053X.

- Brammer, Stephen; Brooks, Chris; Pavelin, Stephen (2009). "The stock performance of America's 100 best corporate citizens" (PDF). The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 49 (3): 1065–1080. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2009.04.001. ISSN 1062-9769.

- Brammer, Stephen; Brooks, Chris; Pavelin, Stephen (2006). "Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures" (PDF). Financial Management. 35 (3): 97–116. doi:10.1111/j.1755-053X.2006.tb00149.x. ISSN 1755-053X.

- Oikonomou, Ioannis; Brooks, Chris; Pavelin, Stephen (2014). "The effects of corporate social performance on the cost of corporate debt and credit ratings" (PDF). Financial Review. 49 (1): 49–75. doi:10.1111/fire.12025. ISSN 1540-6288.

- "Index Literacy". S&P Dow Jones Indices.

- "Methodology Matters". S&P Dow Jones Indices.

- "Indexes". Wilshire Associates.

- "Dow Jones Wilshire > DJ Wilshire 5000/4500 Indexes > Methodology". Wilshire Associates.

- Edwards, Tim; Lazzara, Craig J. (May 2014). "Equal-Weight Benchmarking: Raising the Monkey Bars" (PDF). S&P Global.

- Fabian, David (November 14, 2014). "Checking In On Equal-Weight ETFs This Year". Benzinga.

- S&P methodology via Wikinvest

- Sharpe, William F. (May 2010). "Adaptive Asset Allocation Policies". CFA Institute.

- "Practice Essentials - Equal Weight Indexing" (PDF). S&P Dow Jones Indices.

- Schramm, Michael (September 27, 2019). "What Is Passive Investing?". Morningstar, Inc.

- "SPIVA U.S. Score Card". S&P Dow Jones Indices.

- THUNE, KENT (July 3, 2019). "Why Index Funds Beat Actively Managed Funds". Dotdash.

- Chang, Ellen (May 21, 2019). "How to Choose Between ETFs and Mutual Funds". U.S. News & World Report.

- Amenc, N.; Goltz, F.; Le Sourd, V. (2006). Assessing the Quality of Stock Market Indices. EDHEC Publication.

- Arnott, R. D.; Hsu, J.; Moore, P. (2005). "Fundamental Indexation". Financial Analysts Journal. 60 (2): 83–99. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.612.1314. doi:10.2469/faj.v61.n2.2718. JSTOR 4480658.

- Broby, D. P. (2007). A Guide to Equity Index Construction. Risk Books.

- Fernholz, R.; Garvy, R.; Hannon, J. (1998). "Diversity-Weighted Indexing". Journal of Portfolio Management. 24 (2): 74–82. doi:10.3905/jpm.24.2.74.

- Haugen, R. A.; Baker, N. L. (1991). "The Efficient Market Inefficiency of Capitalization-Weighted Stock Portfolios". Journal of Portfolio Management. 17 (3): 35–40. doi:10.3905/jpm.1991.409335.

- Hsu, Jason (2006). "Cap-Weighted Portfolios are Sub-optimal Portfolios". Journal of Investment Management. 4 (3): 1–10.

External links

![]()