St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, although no longer the principal residence of the monarch, it is the ceremonial meeting place of the Accession Council and the London residence of several minor members of the royal family.

| St James's Palace | |

|---|---|

The north gatehouse, main entrance of St James's Palace in Pall Mall | |

| Location | London, SW1 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°30′17″N 00°08′15″W |

| Built | 1531–1536 |

| Architectural style(s) | Tudor |

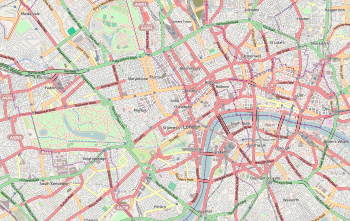

Location of St James's Palace in central London | |

Built by order of Henry VIII in the 1530s on the site of a leper hospital dedicated to Saint James the Less, the palace was secondary in importance to the Palace of Whitehall for most Tudor and Stuart monarchs. The palace increased in importance during the reigns of the early Georgian monarchy, but was displaced by Buckingham Palace in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. After decades of being used increasingly for only formal occasions, the move was formalised by Queen Victoria in 1837. Today the palace houses a number of official offices, societies and collections, and all ambassadors and high commissioners to the United Kingdom are still accredited to the Court of St James's. The palace's Chapel Royal is still used for functions of the British royal family.

Mainly built between 1531 and 1536 in red-brick, the palace's architecture is primarily Tudor in style. A fire in 1809 destroyed parts of the structure, including the monarch's private apartments, which were never replaced. Some 17th-century interiors survive, but most were remodelled in the 19th century.

History

Tudors

The palace was commissioned by Henry VIII on the site of a former leper hospital dedicated to Saint James the Less.[n 1] The new palace, secondary in the king's interest to Henry's Whitehall Palace, was constructed between 1531 and 1536 as a smaller residence to escape formal court life.[2] Much smaller than the nearby Whitehall, St James's was arranged around a number of courtyards, including the Colour Court, the Ambassador's Court and the Friary Court. The most recognisable feature is the north gatehouse; constructed with four storeys, the gatehouse has two crenellated flanking octagonal towers at its corners and a central clock dominating the uppermost floor and gable; the clock is a later addition and dates from 1731.[3] It is decorated with the initials H.A. for Henry and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Henry constructed the palace in red brick, with detail picked out in darker brick.[2]

The palace was remodelled in 1544, with ceilings painted by Hans Holbein and was described as a "pleasant royal house".[4] Two of Henry VIII's children died at Saint James's, Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset and Mary I. [5][6] Elizabeth I often resided at the palace, and is said to have spent the night there while waiting for the Spanish Armada to sail up the Channel.[4]

Stuarts

In 1638, Charles I gave the palace to Marie de Medici, the mother of his wife Henrietta Maria. Marie remained in the palace for three years, but the residence of a Catholic former queen of France proved unpopular with parliament and she was soon asked to leave for Cologne. Charles I spent his final night at St James's before his execution.[1] Oliver Cromwell then took it over, and turned it into barracks during the English Commonwealth period. Charles II, James II, Mary II, and Anne, Queen of Great Britain, were all born at the palace.[1]

The palace was restored by Charles II following the demise of the Commonwealth, laying out St James's Park at the same time. It became the principal residence of the monarch in London in 1698, during the reign of William III and Mary II after Whitehall Palace was destroyed by fire, and became the administrative centre of the monarchy, a role it retains.

House of Hanover

marriage of the future King George V (1893). Royal Collection.

The first two monarchs of the House of Hanover used St James's Palace as their principal London residence. George I and George II both housed their mistresses, the Duchess of Kendal and the Countess of Suffolk respectively, at the palace.[1] In 1757, George II donated the Palace library to the British Museum;[7] this gift was the first part of what later became the Royal Collection.[8] In 1809, a fire destroyed part of the palace, including the monarch's private apartments at the south east corner.[9] These apartments were not replaced, leaving the Queen's Chapel isolated from the rest of the palace by an open area, where Marlborough Road now runs between the two buildings.[10]

George III found St. James's unsuitable. The Tudor palace was regarded as uncomfortable and also as not affording its residents enough privacy, the space to withdraw from the court into family life. In 1762, shortly after his wedding, George purchased Buckingham House – the predecessor to Buckingham Palace – for his queen, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz [11] The royal family began spending the majority of their time at Buckingham House, with St James's used for only formal occasions; thrice-weekly levées and public audiences were still held there. In the late 18th century, George III refurbished the state apartments but neglected the living quarters.[12] Queen Victoria formalised the move in 1837, ending St James's status as the primary residence of the monarch. It was nevertheless where Victoria married her husband, Prince Albert, in 1840, and where, eighteen years later, Victoria and Albert's eldest child, Princess Victoria, married her husband, Prince Frederick of Prussia.[1]

North Front

North Front King's Presence Chamber

King's Presence Chamber Queen's Levée Room

Queen's Levée Room Guard Chamber

Guard Chamber

20th century

The Second Round Table Conference (September – December 1931), pertaining to Indian independence, was held at the palace. On 12 June 1941, Representatives of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, and of the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, and Yugoslavia, as well as General de Gaulle of France, met and signed the Declaration of St James's Palace which was the first of six treaties signed that established the United Nations and composed the Charter of the United Nations.[13]

Today

St James's Palace is still a working palace, and the Royal Court is still formally based there, despite the monarch residing elsewhere. It is also the London residence of the Princess Royal, Princess Beatrice of York, and Princess Alexandra. The palace is used to host official receptions, such as those of visiting heads of state, and charities of which members of the royal family are patrons. The Palace forms part of a sprawling complex of buildings housing Court offices and officials' apartments. The immediate palace complex includes York House, the former home of the Prince of Wales and his sons, Princes William and Harry. Lancaster House, located next-door, is used by HM Government for official receptions, and the nearby Clarence House, the former home of the Queen Mother, is now the residence of the Prince of Wales.[14] The palace also served as the official residence for Princess Eugenie until April 2018.[15]

The nearby Queen's Chapel, built by Inigo Jones, adjoins St James's Palace. While the Queen's Chapel is open to the public at selected times, the Chapel Royal in the palace is not accessible to the public. They both remain active places of worship.[14]

The offices of the Royal Collection Department, the Marshal of the Diplomatic Corps, the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, the Chapel Royal, the Gentlemen at Arms, the Yeomen of the Guard and the Queen's Watermen are all housed at St James's Palace. Since the beginning of the 2000s, the Royal Philatelic Collection has been housed at St James's Palace, after spending the entire 20th century at Buckingham Palace.[14]

On 1 June 2007 the palace, Clarence House and other buildings within its curtilage (other than public pavement on Marlborough Road) were designated as a protected site for the purposes of Section 128 of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005, making it a specific criminal offence for a person to trespass into the site.[16]

See also

- Court of St James's

- List of British Royal residences

Notes

- The uncertainty as to which Saint James was intended is expressed in the 1874 work Old and New London, where the author refers to the dedication as to "St. James the Less, Bishop of Jerusalem". James the Just, brother of Jesus, was referred to as Bishop of Jerusalem, not James the Less.[1]

References

- Walford, Edward (1878). "St James's Palace". Old and New London: Volume 4. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Wagner, John; Walters Schmid, Susan (2011). Encyclopedia of Tudor England. CA, USA: ABC Clio. pp. 1054–1055. ISBN 1598842994.

- British History online Chapter IX: St James's Palace Access date 15 October 2014

- Perry, Maria (1999). The Word of a Prince: A Life of Elizabeth I from Contemporary Documents. Suffolk: Boydell Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0851156330.

- "St James's Palace: History". The British Monarchy. n.d. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Wheatley, Henry; Cunningham, Peter (2011) [1891]. London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 285–287. ISBN 1108028071.

- Warner, George (1912). Queen Mary's Psalter Miniatures and Drawings by an English Artist of the 14th Century Reproduced from Royal Ms. 2 B. Vii in the British Museum (PDF). London: Britism Museum. p. n.

- "Books and Manuscripts". Royal Collection. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- "Royal Residences: St James's Palace". The Royal Family. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- "St. James' Palace: Henry VIII knocked down a hospital for women with leprosy to build another royal residence". The Vintage News. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Nash, Roy (1980). Buckingham Palace: The Place and the People. London: Macdonald Futura. ISBN 978-0354045292.

- Black, Jeremy (2004). George III: America's Last King. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0300142389.

- "1941: The Declaration of St. James' Palace". United Nations. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "St James's Palace: Today". The British Monarchy. n.d. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Perry, Simon (1 May 2018). "Princess Eugenie and Her Fiancé Jack Brooksbank Just Moved Next Door to Harry and Meghan!". People. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Home Office Circular 018 / 2007 (Trespass on protected sites - sections 128-131 of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005)". GOV.UK. Home Office. 22 May 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

Additional reading

- Wolf Burchard, 'St James's Palace: George II and Queen Caroline's Principal London Residence', The Court Historian (2011), pp. 177–203.

- Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: London 6: Westminster (2003), pp 594–601

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. James's Palace. |

.svg.png)