Euston railway station

Euston railway station (/ˈjuːstən/; also known as London Euston) is a central London railway terminus on Euston Road in the London Borough of Camden, managed by Network Rail. It is the southern terminus of the West Coast Main Line to Liverpool Lime Street, Manchester Piccadilly, Edinburgh Waverley and Glasgow Central. It is also the mainline station for services to and through Birmingham New Street, and to Holyhead for connecting ferries to Dublin. Local suburban services from Euston are run by London Overground via the Watford DC Line which runs parallel to the WCML as far as Watford Junction. There is an escalator link from the concourse down to Euston tube station; Euston Square tube station is nearby. King's Cross and St Pancras railway stations are further down Euston Road.

| Euston | |

|---|---|

| London Euston | |

Main entrance in 2009, showing the statue of Robert Stephenson | |

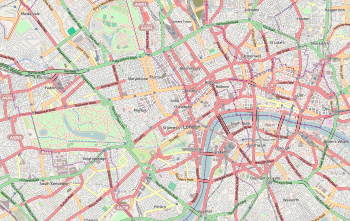

Euston Location of Euston in Central London | |

| Location | Euston Road |

| Local authority | London Borough of Camden |

| Managed by | Network Rail |

| Station code | EUS |

| DfT category | A |

| Number of platforms | 16 |

| Accessible | Yes[1] |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| OSI | Euston Euston Square St Pancras King's Cross |

| Cycle parking | Yes – platforms 17–18 and external |

| Toilet facilities | Yes |

| National Rail annual entry and exit | |

| 2014–15 | |

| – interchange | |

| 2015–16 | |

| – interchange | |

| 2016–17 | |

| – interchange | |

| 2017–18 | |

| – interchange | |

| 2018–19 | |

| – interchange | |

| Railway companies | |

| Original company | London & Birmingham Railway |

| Pre-grouping | London & North Western Railway |

| Post-grouping | London Midland & Scottish Railway |

| Key dates | |

| 20 July 1837 | Opened |

| 1849 | Expanded |

| 1962–1968 | Rebuilt |

| Other information | |

| External links | |

| WGS84 | 51.5284°N 0.1331°W |

London Overground | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key to symbols | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Euston was the first intercity railway terminal in London, planned by George and Robert Stephenson. The original station was designed by Philip Hardwick and built by William Cubitt, having a distinctive arch over the station entrance. The station opened as the terminus of the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) on 20 July 1837. Euston was expanded after the L&BR was amalgamated with other companies to form the London and North Western Railway, leading to the original sheds being replaced by the Great Hall in 1849. Capacity was increased throughout the 19th century from two platforms to fifteen. The station was controversially rebuilt in the mid-1960s, including the demolition of the Arch and the Great Hall, to accommodate the electrified West Coast Main Line, and the revamped station still attracts criticism over its architecture. Euston remains a significant station into the 21st century, and is proposed to be the London terminus of the future High Speed 2 project.

The station is the fifth-busiest station in Britain and the country's busiest inter-city passenger terminal, providing a gateway from London to the West Midlands, North West England, North Wales and Scotland. High-speed intercity services are run by Avanti West Coast and overnight services to Scotland are provided by the Caledonian Sleeper, while regional and commuter services are operated by London Northwestern Railway.

Name and location

The station is named after Euston Hall in Suffolk, the ancestral home of the Dukes of Grafton, the main landowners in the area during the mid-19th century.[4]

Euston station is set back from Euston Square and Euston Road on the London Inner Ring Road, between Cardington Street and Eversholt Street in the London Borough of Camden.[5] It is one of 19 stations in the country that are managed by Network Rail.[6] As of 2016, it is the fifth-busiest station in Britain[lower-alpha 2][7] and the busiest inter-city passenger terminal in the country.[8] It is the sixth-busiest terminus in London by entries and exits.[9][10][11][12] Euston bus station is directly in front of the main entrance.[13]

History

Euston was the first inter-city railway station in London. It opened on 20 July 1837 as the terminus of the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR).[14] The old station building was demolished in the 1960s and replaced with the present building in the international modern style.[15]

The site was chosen in 1831 by George and Robert Stephenson, engineers of the L&BR. The area was mostly farmland at the edge of the expanding city, and adjacent to the New Road (now Euston Road), which had caused urban development.[16][17]

The station and railway have been owned by the L&BR (1837–1846),[18] the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) (1846–1923), the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) (1923–1948),[19] British Railways (1948–1994), Railtrack (1994–2002)[20] and Network Rail (2002–present).[21]

Old station

The original station was built by William Cubitt. The first plan was to construct a building near the Regent's Canal in Islington that would provide a useful connection for London dock traffic, before Robert Stephenson proposed an alternative site at Marble Arch. This was rejected by a provisional committee, and a proposal to end the line at Maiden Lane was rejected by the House of Lords in 1832. A terminus at Camden Town was announced by Stephenson the following year, receiving Royal Assent on 6 May, before an extension was approved in 1834, allowing the line to reach Euston Grove.[16][17]

Initial services were three outward and inwards trains each, reaching Boxmoor in just over an hour. On 9 April 1838, these were extended to a temporary halt at Denbigh Hall, near Bletchley, providing a coach service to Rugby. The permanent link to Curzon Street station in Birmingham, opened on 17 September 1838, covering the 112 miles (180 km) in around 5 1⁄4 hours.[22]

The final gradient from Camden Town to Euston involved a crossing over the Regent's Canal that required a gradient of over 1 in 68. Because steam trains at the time could not climb such an ascent, they were cable-hauled on the down line towards Camden until 1844, after which they used a pilot engine.[23] The L&BR's Act of Parliament prohibited the use of locomotives in the Euston area, following concerns of local residents about noise and smoke from locomotives toiling up the incline.[24]

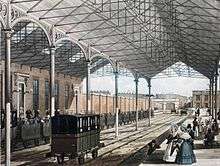

The station building was designed by the classically trained architect Philip Hardwick[25][26] with a 200-foot-long (61 m) trainshed by structural engineer Charles Fox. It had two 420-foot-long (130 m) platforms, one each for departures and arrival. The main entrance portico, known as the Euston Arch was also designed by Hardwick, and was designed to symbolise the arrival of a major new transport system as well as being seen as "the gateway to the north".[27] It was 72 feet (22 m) high, and supported four 44 ft 2 in (13.46 m) by 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) hollow Doric propylaeum columns made from Bramley Fall stone, the largest ever built.[28][29] It was completed in May 1838 and cost £35,000 (now £3,175,000).[27]

The first railway hotels in London were built in Euston. Two hotels designed by Hardwick opened in 1839, located either side of the Arch; the Victoria on the west had basic facilities while the Euston on the east was designed for first-class passengers.[30]

.jpg)

The station grew rapidly as traffic increased. Its workload increased from handling 2,700 parcels a month in 1838 to 52,000 a month in 1841.[18] By 1845, 140 people were working there and trains began to run late because of a lack of capacity.[30] The following year, two new platforms (later 9 and 10) were constructed on vacant land to the west of the station that had been reserved for Great Western Railway services.[31] The L&BR amalgamated with the Manchester & Birmingham Railway and the Grand Junction Railway in 1846 to form the LNWR, with the company headquarters at Euston. This required a new block of offices to be built between the Arch and the platforms.[18]

The station's facilities were greatly expanded with the opening of the Great Hall on 27 May 1849, which replaced the original sheds. It was designed by Hardwick's son Philip Charles Hardwick in classical style, and was 125 ft (38 m) long, 61 ft (19 m) wide and 62 ft (19 m) high, with a coffered ceiling and a sweeping double flight of stairs leading to offices at its northern end.[31] Architectural sculptor John Thomas contributed eight allegorical statues representing the cities served by the line.[32] The station stood on Drummond Street, further back from Euston Road than the front of the modern complex; Drummond Street now terminates at the side of the station but then ran across its front.[33] A short road called Euston Grove ran from Euston Square towards the arch.[34]

An additional bay platform (later platform 7) opened in 1863, and was used for local services to Kensington (Addison Road).[35] The station gained two new platforms (1 and 2) in 1873 along with a separate entrance for cabs from Seymour Street. At the same time, the station roof was raised by 6 feet (1.8 m) to accommodate smoke from the engines more easily.[36]

.jpg)

The continued growth of long-distance railway traffic led to a major expansion along the station's west side starting in 1887. The work involved rerouting Cardington Street over part of the burial ground (later St James's Gardens)[37] of St James's Church, Piccadilly,[38] which was located some way from the church.[39] To avoid public outcry, the remains were reinterred at St Pancras Cemetery.[36] Two extra platforms (4 and 5) opened in 1891,[40] and four further departure platforms (now platforms 12–15) opened on 1 July 1892, bringing the total to fifteen, along with a separate booking office on Drummond Street.[36][14]

_p136_-_Euston_Station_(plan).jpg)

The line between Euston and Camden was doubled between 1901 and 1906.[41] A new booking hall opened in 1914, constructed on part of the cab yard. The Great Hall was fully redecorated and refurbished between 1915 and 1916, and again in 1927.[42] The station's ownership was transferred to the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) in the 1923 grouping.[19]

Apart from the lodges on Euston Road and statues now on the forecourt, few relics of the old station survive.[43] The National Railway Museum's collection at York includes Edward Hodges Baily's statue of George Stephenson, both from the Great Hall;[44] the entrance gates;[45] and an 1846 turntable discovered during demolition.[46]

London, Midland and Scottish Railway redevelopment

By the 1930s Euston had become congested, and the LMS considered rebuilding it. In 1931 it was reported that a site for a new station was being sought, with the most likely option being behind the existing station in the direction of Camden Town.[47] The LMS announced in 1935 that the station (including the hotel and offices) would be rebuilt using a government loan guarantee.[48]

In 1937 it appointed the architect Percy Thomas to produce designs.[49] He proposed a new American-inspired station that would involve removing or resiting the arch, and included office frontages along Euston Road and a helicopter pad on the roof.[48][50] The redevelopment work began on 12 July 1938, when 100,000 long tons (100,000 tonnes) of limestone was extracted for the new building and some new flats constructed to rehouse people displaced by the works. The project was then shelved indefinitely because of World War II.[48]

The station was damaged several times during the Blitz in 1940. Part of the Great Hall's roof was destroyed, and a bomb landed between platforms 2 and 3, destroying offices and part of the hotel.[48]

New station

By the 1950s, passengers considered Euston to be in squalor and covered in soot, leading to a full redecoration and restoration in 1953. Ticket machines were modernised. The Arch was now surrounded by further property development and kiosks, and was in need of restoration.[51]

British Railways announced a complete rebuild of Euston that could accommodate a fully electrified West Coast Main Line in 1959.[51] Because of the restricted layout of track and tunnels at the northern end, enlargement could be accomplished only by expanding southwards over the area occupied by the Great Hall and the Arch.[51][52] Consequently, the London County Council were given notice that the Arch and the Great Hall would be demolished, which was granted on the proviso that the Arch would be restored and re-sited. This was financially unviable as BR estimated it would cost at least £190,000 (now £5,340,000).[51]

The Arch demolition was formally announced by the Minister of Transport, Ernest Marples in July 1961, but immediately drew widespread protest. Experts did not believe the £190,000 estimate and suspected foreign firms could move the Arch on rollers for substantially less. The Earl of Euston, the Earl of Rosse and John Betjeman all protested against the redevelopment. On 16 October 75 architects and students staged a formal demonstration against the demolition inside the Great Hall, and a week later Sir Charles Wheeler led a deputation to speak with the Prime Minister Harold Macmillan against the demolition. Macmillan replied that as well as the cost, there was no place large enough to put the Arch that would look in keeping with its surroundings. Demolition began on 6 November and was completed within four months.[53] Since 1996, proposals have been formulated to reconstruct it as part of the planned redevelopment of the station,[54] including the station's use as the London terminus of the High Speed 2 line.[55]

The new station was constructed by Taylor Woodrow Construction to a design by London Midland Region architects of British Railways, William Robert Headley and Ray Moorcroft,[56] in consultation with Richard Seifert & Partners.[57] Redevelopment began in summer 1962 and progressed from east to west, including the demolition of the Great Hall, while a 11,000-square-foot (1,000 m2) temporary building housed ticket offices and essential facilities.[53] The project was planned to keep Euston working to 80% capacity during the works, with at least 11 platforms in operation at any time.[58] While services were diverted elsewhere where practical, the station remained operational throughout the works.[53]

The first phase of construction involved building 18 new platforms with two track bays to handle parcels above this, along with a signal and communications building and various staff offices. The parcel deck was reinforced by 5,500 tons of structural steelwork.[58] The signalling on the main routes leading out of the station was completely reworked along with the electrification of the lines, including the British Rail Automatic Warning System.[59] Fifteen platforms had been completed by 1966, and the full electric service began on 3 January. A fully automated parcel depot, sited above platforms 3 to 18, opened on 7 August 1966.[15] The new station was opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 14 October 1968.[60]

The station is a long, low structure, 200 feet (61 m) wide and 150 feet (46 m) deep under a 36-foot (11 m) high roof. It opened with integrated automatic ticket facilities and a wide variety of shops; the first of its kind for any British station.[60]

The original plan was to construct office buildings over the station, whose rents would help fund the cost of the rebuilding, but this was scrapped after a government White Paper was released in 1963 that restricted the rate of commercial office development in London.[15] A second development phase by Richard Seifert & Partners began in 1979, adding 405,000 square feet (37,600 m2) of office space along the front of the station in the form of three low-rise towers overlooking Melton Street and Eversholt Street.[61] The offices were occupied by British Rail,[62] then by Railtrack, and finally by Network Rail, which has now vacated[lower-alpha 3] all but a small portion of one of the towers. These buildings are in a functional style; the main facing material is polished dark stone, complemented by white tiles, exposed concrete and plain glazing.[63]

The station has a single large concourse, separate from the train shed. Originally, there were no seats installed there to deter vagrants and crime, but these were added following complaints from passengers.[61] A few remnants of the older station remain: two Portland stone entrance lodges and a war memorial. A statue of Robert Stephenson by Carlo Marochetti, previously in the old ticket hall, stands in the forecourt.[43]

There is a large statue by Eduardo Paolozzi named Piscator dedicated to German theatre director Erwin Piscator at the front of the courtyard, which as of 2016 is reported as deteriorating.[64] Other pieces of public art, including low stone benches by Paul de Monchaux around the courtyard, were commissioned by Network Rail in 1990.[65] The station has catering units and shops, a large ticket hall and an enclosed car park with over 200 spaces.[66] The lack of daylight on the platforms compares unfavourably with the glazed trainshed roofs of traditional Victorian railway stations, but the use of the space above as a parcels depot released the maximum space at ground level for platforms and passenger facilities.[67]

Privatisation

Ownership of the station transferred from British Rail to Railtrack in 1994, passing to Network Rail in 2002 following the collapse of Railtrack.[21] In 2005 Network Rail was reported to have long-term aspirations to redevelop the station, removing the 1960s buildings and providing more commercial space by using the "air rights" above the platforms.[68]

In 2007, British Land announced that it had won the tender to demolish and rebuild the station, spending some £250 million of its overall redevelopment budget of £1 billion for the area. The number of platforms would increase from 18 to 21.[69] In 2008, it was reported that the Arch could be rebuilt.[70] In September 2011, the demolition plans were cancelled, and Aedas was appointed to give the station a makeover.[71]

In July 2014 a statue of navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders, who circumnavigated the globe and charted Australia, was unveiled at Euston; his grave was rumoured to lie under platform 15 at the station,[72] but had been relocated during the original station construction and in 2019 was found behind the station during excavation work for the HS2 line.[38][73]

High Speed 2

In March 2010 the Secretary of State for Transport, Andrew Adonis announced that Euston was the preferred southern terminus of the proposed High Speed 2 line, which would connect to a newly-built station near Curzon Street and Fazeley Street in Birmingham.[74] This would require expansion to the south and west to create new sufficiently long platforms. These plans involved a complete reconstruction, involving the demolition of 220 Camden Council flats, with half the station providing conventional train services and the new half high-speed trains. The Command Paper suggested rebuilding the Arch, and included an artist's impression of it.[75]

The station will have 24 platforms serving both high-speed and ordinary lines at a low level. The flats demolished for the extension would be replaced by significant building work above. The underground station would be rebuilt and connected to Euston Square station. As part of the extension beyond Birmingham, the Mayor of London's office believed it will be necessary to build the proposed Crossrail 2 line via Euston to relieve 10,000 extra passengers forecast to arrive during an average day.[76][77][78][79]

To relieve pressure on Euston during and after rebuilding for High Speed 2, HS2 Ltd has proposed the diversion of some services to Old Oak Common (for Crossrail). This would include eight commuter trains per hour originating/terminating between Tring and Milton Keynes Central inclusive.[80] In 2016, the Mayor Sadiq Khan endorsed the plans and suggested that all services should terminate at Old Oak Common while a more appropriate solution is found for Euston.[81]

The current scheme does not provide any direct access between High Speed 2 at Euston and the existing High Speed 1 from St Pancras. In 2015, plans were announced to link the two stations via a travelator service.[82] Platforms 17 and 18 closed in May and June 2019 for High Speed 2 preparation work.[83][84]

Preparation for the 2019 start of tunnelling works for the Euston approach was made with the demolition in 2018 of the Euston Downside Carriage Maintenance Depot.[85]

Criticism

Euston's 1960s style of architecture has been described as "a dingy, grey, horizontal nothingness"[86] and a reflection of "the tawdry glamour of its time", entirely lacking in "the sense of occasion, of adventure, that the great Victorian termini gave to the traveller".[87] Writing in The Times, Richard Morrison stated that "even by the bleak standards of Sixties architecture, Euston is one of the nastiest concrete boxes in London ... The design should never have left the drawing-board".[88] Michael Palin, explorer and travel writer, in his contribution to Great Railway Journeys titled "Confessions of a Trainspotter", likened it to "a great bath, full of smooth, slippery surfaces where people can be sloshed about efficiently".[89]

Access to parts of the station is difficult for people with physical disability. The introduction of lifts in 2010 made the taxi rank and underground station accessible from the concourse, though customers found them unreliable and frequently broken down.[90] Wayfindr technology was introduced to the station in 2015 to help the visually impaired navigate the station.[91]

The demolition of the original buildings in 1962 has been described as "one of the greatest acts of Post-War architectural vandalism in Britain" and is believed to have been approved directly by Harold Macmillan, the first of a line of Prime Ministers who championed motorway building. The replacement trainshed has a low, flat roof, making no attempt to match the airy style of London's major 19th century trainsheds. The attempts made to preserve the earlier building, championed by Sir John Betjeman, led to the formation of the Victorian Society and heralded the modern conservation movement.[92] This movement saved the nearby high Gothic St Pancras station when threatened with demolition in 1966,[93] ultimately leading to its renovation in 2007 as the terminus of HS1 to the Continent.[94]

Incidents

On 26 April 1924, an electric multiple unit collided with the rear of an excursion train carrying passengers from the FA Cup Final in Coventry.[95] Five passengers were killed. The accident was blamed on poor visibility owing to smoke and steam under the Park Street Bridge.[96]

On 27 August 1928, a passenger train collided with the buffer stops. Thirty people were injured.[97]

On 10 November 1938, a suburban service collided with empty coaches after a signal was misinterpreted. 23 people were injured.[96]

On 6 August 1949, an empty train was accidentally routed towards a service for Manchester, colliding with it at about 5 mph (8 km/h). The accident was blamed on a lack of track circuiting and no proper indication of when platforms were occupied.[96]

1973 IRA attack

Extensive but superficial damage was caused by an IRA bomb that exploded close to a snack bar at approximately 1:10 pm on 10 September 1973, injuring eight people.[98] A similar explosive had detonated 50 minutes earlier at King's Cross.[99] The Metropolitan Police had received a three-minute warning,[98] and were unable to evacuate the station completely, but British Transport Police managed to clear much of the area just before the explosion.[100] In 1974, the mentally ill Judith Ward confessed to the bombing and was convicted of this and other crimes, despite the evidence against her being highly suspect and Ward retracting her confessions. She was acquitted in 1992; the true culprit has yet to be identified.[101]

National Rail services

Euston has services from four different train operators:

Avanti West Coast operates InterCity West Coast services:[102]

- 1 train per hour to Glasgow Central / Edinburgh Waverley (alternating) via Birmingham

- 1 to Glasgow Central via Preston. Additional services operate to/from Preston, Lancaster, Carlisle during peak times

- 2 to Birmingham New Street via Coventry, extended to/from Wolverhampton (at peak hours)

- 3 to Manchester Piccadilly via Stockport:

- 2 via Stoke-on-Trent

- 1 via Crewe

- 1 to Liverpool Lime Street via Stafford, Crewe and Runcorn

- 1 to Chester via Crewe, with certain trains extended along the North Wales Coast Line to Bangor or Holyhead for the ferries to Ireland, such as Irish Ferries as well as Stena Line to Dublin Port, one train on Mon-Fri to Wrexham General[103]

- 2 trains per day to Shrewsbury[104]

- 4 trains per day on Monday-Friday to Blackpool North

London Northwestern Railway operates regional and commuter services.[105]

- 2 trains per hour to Tring

- 1 to Milton Keynes Central

- 2 to Birmingham New Street via Northampton

- 1 to Northampton

- 1 to Crewe via Stafford

- 1 to Liverpool Lime Street via Birmingham New Street

London Overground operates local commuter services.

- 4 trains per hour to Watford Junction via the Watford DC Line[106]

Caledonian Sleeper operates two nightly services to Scotland from Sunday to Friday inclusive.[107]

- Highland sleeper to Aberdeen via Kirkcaldy and Dundee, Fort William via Dalmuir, and Inverness via Stirling and Perth

- Lowland sleeper to Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Waverley via Carlisle

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

South Hampstead towards Watford Junction | Watford DC Line | Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction | Caledonian Sleeper Lowland Caledonian Sleeper |

Terminus | ||

| Crewe | Caledonian Sleeper Highland Caledonian Sleeper (southbound) |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction | Caledonian Sleeper Highland Caledonian Sleeper (northbound) |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Milton Keynes Central | London Northwestern Railway London – Crewe |

Terminus | ||

| Harrow & Wealdstone or Watford Junction or Leighton Buzzard | London Northwestern Railway London-Milton Keynes Central/Northampton/Birmingham |

Terminus | ||

| Harrow & Wealdstone or Wembley Central or Watford Junction | London Northwestern Railway London Euston-Tring |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Milton Keynes Central or Coventry or Rugby | Avanti West Coast WCML London-West Midlands |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Rugby | Avanti West Coast WCML London – Shrewsbury |

Terminus | ||

| Rugby | Avanti West Coast WCML London – Blackpool |

Terminus | ||

| Milton Keynes Central or Nuneaton | Avanti West Coast WCML London – Chester/North Wales/Holyhead for Dublin |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Milton Keynes Central or Stafford or Crewe or Runcorn | Avanti West Coast WCML London – Liverpool |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Milton Keynes Central or Stafford or Stoke-on-Trent or Crewe | Avanti West Coast WCML London – Manchester |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Milton Keynes Central or Stafford or Crewe | Avanti West Coast WCML London-Crewe |

Terminus | ||

| Watford Junction or Milton Keynes Central or Tamworth or Warrington Bank Quay or Preston | Avanti West Coast WCML London-Glasgow/North West |

Terminus | ||

| Milton Keynes Central or Warrington Bank Quay | Avanti West Coast WCML London-Edinburgh |

Terminus | ||

| Future services | ||||

| Old Oak Common | Avanti West Coast High Speed 2 |

Terminus | ||

| Milton Keynes Central | Grand Central WCML London-Blackpool |

Terminus | ||

London Underground

Euston was poorly served by the early London Underground network. The nearest station on the Metropolitan line was Gower Street, around five minutes' walk away. A permanent connection did not appear until 12 May 1907, when the City & South London Railway opened an extension west from Angel. The Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway opened an adjacent station on 22 June in the same year; these two stations are now part of the Northern line. Gower Street station was quickly renamed Euston Square in response.[42] A connection to the Victoria line opened on 1 December 1968.[60]

The underground network around Euston is planned to change depending on the construction of High Speed 2. Transport for London (TfL) plans to change the safeguarded route for the proposed Chelsea–Hackney line to include Euston between Tottenham Court Road and King's Cross St Pancras.[108] As part of the rebuilding work for High Speed 2, it is proposed to integrate Euston and Euston Square into a single tube station.[77]

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Great Portland Street towards Hammersmith | Circle line Transfer at: Euston Square | King's Cross St. Pancras towards Edgware Road (via Aldgate) |

||

| Hammersmith & City line Transfer at: Euston Square | King's Cross St. Pancras towards Barking |

|||

Great Portland Street towards Amersham, Chesham, Uxbridge or Watford | Metropolitan line Transfer at: Euston Square | King's Cross St. Pancras towards Aldgate |

||

Mornington Crescent towards Edgware, Mill Hill East or High Barnet | Northern line Charing Cross branch Transfer at: Euston | Warren Street towards Kennington or Morden (via Charing Cross) |

||

Camden Town towards Edgware, Mill Hill East or High Barnet | Northern line Bank branch Transfer at: Euston | King's Cross St. Pancras towards Morden (via Bank) |

||

Warren Street towards Brixton | Victoria line Transfer at: Euston | King's Cross St. Pancras towards Walthamstow Central |

See also

- Birmingham Curzon Street railway station (1838-1966) - the Birmingham counterpart to the original Euston station

- Pennsylvania Station (1910–1963) – a similarly demolished and rebuilt station

References

Notes

- This decrease was caused by a change in methodology which reduced the figure by 3.519 million. Without the change, the figure would have been 45.197 million.

- The busier stations are Waterloo, Victoria, Liverpool Street and London Bridge

- Many staff transferred to a new complex in Milton Keynes, see Quadrant:mk

Citations

- "London and South East" (PDF). National Rail. September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009.

- "Out of Station Interchanges" (XLS). Transport for London. 19 February 2019.

- "Station usage estimates". Rail statistics. Office of Rail Regulation. Please note: Some methodology may vary year on year.

- "The Family". Euston Hall, Suffolk. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Euston Station". Google Maps. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Commercial information". Our Stations. London: Network Rail. April 2014. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "Britain's most and least used train stations revealed, with one getting just 12 passengers a year". The Daily Telegraph. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Digitising Euston". Rail Engineer. 5 August 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Station Usage 2007/08" (PDF). Network Rail. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- "Stations Run by Network Rail". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- "Station facilities for London Euston". National Rail Enquiries. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- "Commercial information" (PDF). Complete National Rail Timetable. London: Network Rail. May 2013. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "Euston Bus Station". Transport for London.

- "Euston Station, London". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Jackson 1984, p. 54.

- Jackson 1984, p. 31.

- British Rail 1968, p. 5.

- British Rail 1968, p. 8.

- Jackson 1984, p. 46.

- "Brexit to bring back BR? What could the vote mean for our railways". rail.co.uk. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Interview: Network Rail CFO Patrick Butcher". Financial Director. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Jackson 1984, p. 38.

- Jackson 1984, p. 32.

- "London and Birmingham Railway". Camden Railway Heritage Trust. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Jackson 1984, p. 35.

- Cole 2011, p. 107.

- Jackson 1984, p. 37.

- Jackson 1984, pp. 35–37.

- Pile 2005, p. 232.

- Jackson 1984, p. 39.

- Jackson 1984, p. 40.

- Biddle & Nock 1983, p. 214.

- www.motco.com Archived 18 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine – 1862 map, showing position of 1849 station.

- Cain, Joe. "Euston Grove, History of a Street". University College London. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Jackson 1984, p. 42.

- Jackson 1984, p. 43.

- Location of St James's burial ground 51.52849°N 0.13702°W

- "Remains of Captain Matthew Flinders discovered at HS2 site in Euston". UK Government. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "St. James Church, Hampstead Road". Survey of London: volume 21: The parish of St Pancras part 3: Tottenham Court Road & Neighbourhood. 1949. pp. 123–136. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- McCarthy & McCarthy 2009, p. 71.

- Jackson 1984, p. 44.

- Jackson 1984, pp. 45–46.

- Jackson 1984, p. 56.

- "State of George Stephenson". National Railway Museum. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Euston Station gates". National Railway Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Turntable, Cast Iron, London and Birmingham Railway". National Railway Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "New Euston Station". Western Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 30 January 1931. Retrieved 27 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Jackson 1984, p. 48.

- "Reconstruction of Euston Station". Sheffield Independent. British Newspaper Archive. 27 February 1937. Retrieved 27 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Bull, John. "The Euston Arch Part 2: Death". London Reconnections. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Jackson 1984, p. 50.

- The New Euston Station 1968. British Rail information booklet.

- Jackson 1984, p. 53.

- Keilthy, Paul (7 May 2009). "Arrival of Euston station arch delayed..._until 2012". Camden New Journal. London. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- "Crewe and Camden could benefit from HS2 rethink". Construction Manager. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "C20 Society fails in bid to list Euston station". The Architects' Journal. The Twentieth Century Society. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Building of the Month. November 2011". The Twentieth Century Society. The Twentieth Century Society. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- British Rail 1968, p. 12.

- British Rail 1968, p. 15.

- Jackson 1984, p. 55.

- Jackson 1984, p. 345.

- Gourvish & Anson 2004, p. 37.

- "The notorious work of Richard Seifert". Building Magazine. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- Alberge, Dalya (28 November 2016). "Major Paolozzi sculpture facing decay 'because no one wants to own it'". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- De Monchaux, Paul. "Portland Bench 1990". Paul de Monchaux Sculpture. Paul de Monchaux. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Station Facilities for London Euston". ATOC. n.d. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- British Rail 1968, p. 13.

- Carmona & Wunderlich 2013, p. 146.

- Stewart, Dan (5 April 2007). "British Land wins £1bn Euston contract". Building.

- Binney, Marcus (18 February 2008). "Landmark of the railway age may be resurrected". The Times. London.(subscription required)

- "Euston Station". Aedas. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Higgitt, Rebekah (18 July 2014). "Matthew Flinders bicentenary: statue unveiled to the most famous navigator you've probably never heard of". The Guardian Science blog. London. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Flynn, Meagan (25 January 2019). "The explorer who literally put Australia on the map is found buried beneath a London train station". The Washington Post – via San Francisco Chronicle.

- Department for Transport (2010a). High Speed Rail – Command Paper (PDF). The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-10-178272-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "High Speed Rail (Command Paper)" (PDF). Department for Transport. March 2010. p. 104. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2010.

- Cecil, Nicholas (28 February 2011). "High-speed trains 'will increase passenger numbers by 10,000' at Euston station". London Evening Standard.

- "Transport Select Committee". HM Government. 28 June 2011.

- "Subject: Proposal for Examining the Potential Effect of High Speed 2 on London's Transport Network". Greater London Authority. 17 May 2011.

- "High Speed Rail: Investing in Britain's Future Consultation" (PDF). Department for Transport. February 2011.

- "High Speed Rail London to the West Midlands and Beyond: A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited: part 3 of 11" (PDF). High Speed Two Limited. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Crerar, Pippa (5 October 2016). "Mayor Sadiq Khan: HS2 'must find solution' to Euston station plans". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Lefty, Mark (11 July 2015). "HS2: Plans revived to connect London terminus of High Speed Two with Channel Tunnel Rail Link". The Independent. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Euston Platforms 17 and 18 to be decommissioned". Today's Railways UK. No. 262. October 2018. p. 9.

- Euston Platform 17b to close on 19 May Today's Railways UK issue 209 May 2019 page 20

- "First look at HS2's Euston tunnel portal site". GOV.UK. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Martin, Andrew (13 December 2004). "So, what would you burn?". New Statesman. London. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Stamp, Gavin (October 2007). "Steam ahead: the proposed rebuilding of London's Euston station is an opportunity to atone for a great architectural crime". Apollo: the international magazine of art and antiques. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Morrison, Richard (10 April 2007). "Euston: we have an architectural problem". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 September 2007. (subscription required)

- "An Ode To Euston Station". Londonist. 12 April 2016.

- Accessibility on the Transport Network (PDF) (Report). Greater London Authority. p. 13. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Holloway, Cathy (6 June 2017). "Existing transport is failing disabled people, but new tech may help". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ""How We Built Britain" exhibition". Royal Institution of British Architects. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- Jackson 1984, p. 73.

- "Eurostar opens for business at St Pancras International station" (Press release). Eurostar. 14 November 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Hall 1990, p. 93.

- Jackson 1984, p. 57.

- Trevena 1980, p. 35.

- "On This Day 1973: "Bomb blasts rock Central London"". BBC News. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Jones 2016, p. 411.

- Jones 2016, p. 348.

- "On this Day 1974: M62 bomber jailed for life". BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "London and the West Midlands – North West and Scotland". Virgin Trains. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "London and the West Midlands – North Wales". Virgin Trains. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "National Rail Timetable – May 2018 – Table T066-F" (PDF). Network Rail. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Timetables for London Euston". London Midland. Select an individual timetable to verify the services. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "Watford Junction to Euston" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Caledonian Sleeper". ScotRail. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "HS2 fuels Crossrail 2 business case". TransportXtra. 21 December 2010.

Sources

- Biddle, Gordon; Nock, Oswald Stevens (1983). The railway heritage of Britain: 150 years of railway architecture and engineering. M. Joseph. ISBN 978-0-718-12355-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carmona, Matthew; Wunderlich, Filipa Matos (2013). Capital Spaces: The Multiple Complex Public Spaces of a Global City. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-31196-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cole, Beverly (2011). Trains. Potsdam, Germany: H.F.Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0516-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gourvish, Terry; Anson, Mike (2004). British Rail 1974–1997 : From Integration to Privatisation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19926-909-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, Stanley (1990). The Railway Detectives. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0 7110 1929 0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Alan (1984) [1969]. London's Termini. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-330-02747-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Ian (2016). London: Bombed Blitzed and Blown Up: The British Capital Under Attack Since 1867. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-473-87899-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCarthy, Colin; McCarthy, David (2009). Railways of Britain – London North of the Thames. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3346-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pile, John (2005). A History of Interior Design. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-856-69418-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trevena, Arthur (1980). Trains in Trouble. Vol. 1. Redruth: Atlantic Books. ISBN 0-906899-01-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The New Euston Station (PDF) (Report). British Rail. 1968. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Euston station. |

- Station information on Euston railway station from Network Rail

- Euston Station and railway works – information about the old station from the Survey of London online.

- Euston Station Panorama