Scarborough Shoal

Scarborough Shoal, also known as Huangyan Dao,[1] Panatag Shoal (Filipino: Kulumpol ng Panatag),[2] Bajo de Masinloc (Spanish),[3] and Democracy Reef are two rocks[lower-alpha 1] in a shoal located between the Macclesfield Bank and Luzon island in the South China Sea.

| Disputed island Other names: Scarborough Reef Huangyan Dao Democracy Reef Panatag Shoal Panacot Shoal | |

|---|---|

Scarborough Shoal prior to the Chinese-imposed destruction of the reefs

Scarborough Shoal | |

| Geography | |

| Location | South China Sea |

| Coordinates | 15°11′N 117°46′E |

| Total islands | 2 islets with many reefs |

| Major islands | 1 |

| Highest point |

|

| Claimed by | |

| People's Republic of China | |

| Prefecture-level city | Sansha, Hainan |

| Republic of China (Taiwan) | |

| Philippines | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

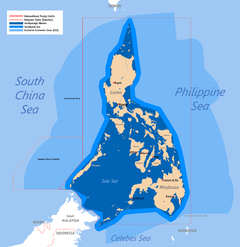

It is a disputed territory claimed by the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan) and the Philippines. The shoal's status is often discussed in conjunction with other territorial disputes in the South China Sea such as those involving the Spratly Islands, and the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff. It formerly was administered by the Philippines, however, due to the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, where China sent warships to invade the shoal, the administration of the shoal was taken by the People's Republic of China. It was initially expected for the United States to defend the territory of the Philippines during the standoff as the two nations had a Mutual Defense Treaty, however, the United States chose to move itself away from the tension, and used 'verbal protests' against China instead. The aftermath of the standoff ultimately strained Philippines-China relations and Philippines-United States relations, resulting in Filipino officials calling the United States an 'unreliable ally', a statement echoed by other nations. The event also solidified China's expansionist ideals in the Asia-Pacific region.[4][5][6] In 2013, the Philippines solely filed an international case against China in the UN-backed court in The Hague, Netherlands. In 2016, the court officially dismissed China's so-called "9-dash claim" in the entire South China Sea and upheld the Philippine claim.[7] China rejected the UN-backed international court's decision and sent more warships in Scarborough Shoal and other islands controlled by China.[8]

The shoal was named by Captain Philip D'Auvergne, whose East India Company East Indiaman Scarborough grounded on one of the rocks on 12 September 1784, before sailing on to China.[9][10]

Geography

Scarborough Shoal forms a triangle-shaped chain of reefs and rocks with a perimeter of 46 km (29 mi). It covers an area of 150 km2 (58 sq mi), including an inner lagoon. The shoal's highest point, South Rock, is 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) above sea-level at high tide. Located north of it is a channel, approximately 370 m (1,214 ft) wide and 9–11 m (30–36 ft) deep, leading into the lagoon. Several other coral rocks encircle the lagoon, forming a large atoll.[2]

The shoal is about 198 kilometres (123 mi) west of Subic Bay. To the east of the shoal is the 5,000–6,000 m (16,000–20,000 ft) deep Manila Trench. The nearest landmass is Palauig, Zambales on Luzon island in the Philippines, 220 km (137 mi) due east.

History

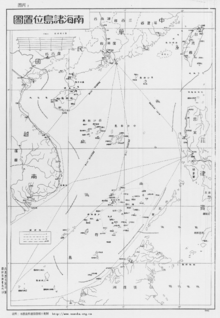

A number of countries have made historic claims of the use of Scarborough Shoal. China has claimed that a 1279 Yuan dynasty map and subsequent surveys by the royal astronomer Guo Shoujing carried out during Kublai Khan's reign established that Scarborough Shoal (then called Zhongsha islands) were used since the thirteenth century by Chinese fishermen. However, no such 1279 map has been released by China to the public.[11]

.jpg)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas. |

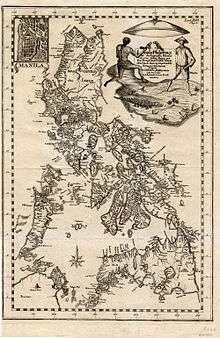

During the Spanish period of the Philippines, a 1734 map was made, which clearly named Scarborough Shoals as Panacot, a feature under complete sovereignty of Spanish Philippines. The shoal's current name was chosen by Captain Philip D'Auvergne, whose East India Company East Indiaman Scarborough briefly grounded on one of the rocks on 12 September 1784, before sailing on to China. When the Philippines was granted independence in the 19th century and 20th century, Scarborough Shoal was passed by the colonial governments to the sovereign Republic of the Philippines.[9][10]

The 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff between China and the Philippines led to a situation where access to the shoal was restricted by the People's Republic of China. The expected intervention of the United States to protect its ally through an existing mutual defense treaty did not commence after the United States indirectly stated that it does not recognize any nation's sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal, leading to strained ties between the Philippines and the United States.[12] In January 2013, the Philippines formally initiated arbitration proceedings against China's claim on the territories within the "nine-dash line" that includes Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal, which it said is "unlawful" under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[13][14] An arbitration tribunal was constituted under Annex VII of UNCLOS and it was decided in July 2013 that the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) would function as registry and provide administrative duties in the proceedings.[15]

On 12 July 2016, the arbitrators of the tribunal of PCA agreed unanimously with the Philippines. They concluded in the award that there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or resources, hence there was "no legal basis for China to claim historic rights" over the nine-dash line.[16] Accordingly, the PCA tribunal decision is ruled as final and non-appealable by either countries.[17][18] The tribunal also criticized China's land reclamation projects and its construction of artificial islands in the Spratly Islands, saying that it had caused "severe harm to the coral reef environment".[19] It also characterized Taiping Island and other features of the Spratly Islands as "rocks" under UNCLOS, and therefore are not entitled to a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone.[20] China however rejected the ruling, calling it "ill-founded".[21] Taiwan, which currently administers Taiping Island, the largest of the Spratly Islands, also rejected the ruling.[22]

In late 2016, following meetings between the Philippine president Duterte and his PRC counterparts, the PRC "verbally" allowed Filipino fishermen to access the shoals for fishing, sparking criticism as "allowing" would mean China is implying that it owns the territory.[23] In January 2018, it was revealed that for every 3,000 pesos' worth of fish catch by Filipino fisherfolk, China took them in exchange for "two bottles of mineral water" worth 20 pesos.[24] In June 14, 2018, China's destruction of Scarborough Shoal's reefs surged to an extent which they became visible via satellites, as confirmed by the University of the Philippines Diliman.[25]

Land reclamation and other activities in the surrounding area

The shoal and its surrounding area are rich fishing grounds. The atoll's lagoon provides some protection for fishing boats during inclement weather.

There are thick layers of guano lying on the rocks in the area. Several diving excursions and amateur radio operations, DX-peditions (1994, 1995, 1997 and 2007), have been carried out in the area.[26]

At various times between 1951 and 1991, U.S. and Philippine military forces operating from Philippine bases routinely employed various types of live and inert ordnance at Scarborough Shoal for exercises and other training. It is possible that much of this expended ordnance remains on the ocean floor, posing a hazard to anyone attempting to disturb the shoal or the surrounding ocean areas. A CBS News expose revealed that fishermen here were more distressed by the pollution caused by the Masinloc thermal power plant and local Barangay corruption than by any PRC activities.[27]

In July 2015, Filipino fishermen discovered large buoys and containment booms in Scarborough shoal, and assumed them to be of PRC origin. They were removed and towed back to the Philippine coast.[28] In March 2016, in its Scarborough Contingency plan, the CSIS Asia Maritime transparency Initiative reported that satellite imagery had shown no signs of any land reclamation, dredging or construction activities in Scarborough shoal.[29] Only one small Chinese civilian ship and two small Filipino trimaran fishing boats (bangkas) were seen, as has been normal for the past few years.[30]

In September 2016 during the ASEAN summit, the Philippine government claimed that a number of Chinese ships capable of land reclamation had collected at Scarborough shoal. This claim was denied by the PRC government.[31]

Also in September 2016, the New York Times reported that PRC activities at the Shoal continued in the form of naval patrols and hydrographic surveys.[32] The PRC navy restricted Filipino fishermen access to the shoal from 2012 until August 2016, at which time PRC authorities started to allow Filipino fishermen to resume fishing in the shoal after talks between the Philippine President Duterte and his Chinese counterparts.[23] However fishermen were prohibited from using dynamite fishing or other methods, including clam digging, that could harm the ecology of the reefs.[23]

In January 2017, the International Business Times reported the possibility of land reclamation at Scarborough shoal by the PRC. However, photos of the shoal posted by CSIS have, to date, not shown any evidence of reclamation activity.[23][33]

Sovereignty dispute

Claims by China and Taiwan

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to China's nine-dash demarcation line. |

The People's Republic of China and Taiwan claim that Chinese people discovered the shoal centuries ago and that there is a long history of Chinese fishing activity in the area. The shoal lies within the nine-dotted line drawn by China on maps marking its claim to islands and relevant waters consistent with United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) within the South China Sea.[34] An article published in May 2012 in the PLA Daily states that Chinese astronomer Guo Shoujing went to the island in 1279, under the Yuan dynasty, as part of an empire-wide survey called "Measurement of the Four Seas" (四海測驗), however, no such 13th century map has been made public by China nor such evidence on the existence of the map is known.[35] In 1979 historical geographer Han Zhenhua (韩振华) was among the first scholars to claim that the point called "Nanhai" (literally, "South Sea") in that astronomical survey referred to Scarborough Shoal.[36] In 1980 during a conflict with Vietnam for sovereignty over the Paracel Islands (Xisha Islands), however, the Chinese government issued an official document claiming that "Nanhai" in the 1279 survey was located in the Paracels.[37] Historical geographer Niu Zhongxun defended this view in several articles.[38] In 1990, a historian called Zeng Zhaoxuan (曾昭璇) argued instead that the Nanhai measuring point was located in Central Vietnam.[39] Historian of astronomy Chen Meidong (陈美东) and historian of Chinese science Nathan Sivin have since agreed with Zeng's position in their respective books about Guo Shoujing.[40][41]

In 1935, China, as the Republic of China (ROC), regarded the shoal as part of the Zhongsha Islands. That position has since been maintained by both the ROC, which now governs Taiwan, and the People's Republic of China (PRC).[42] In 1947 the shoal was given the name Minzhu Jiao (Chinese: 民主礁; literally: 'Democracy Reef'). In 1983 the People's Republic of China renamed it Huangyan Island with Minzhu Jiao reserved as a second name.[43] In 1956 Beijing protested Philippine remarks that the South China Sea islands in close proximity to Philippine territory should belong to the Philippines. China's Declaration on the territorial Sea, promulgated in 1958, says in part,

The breadth of the Territorial Sea of the People's Republic of China shall be twelve nautical miles. This applies to all territories of the People's Republic of China, including the Chinese mainland and its coastal islands, as well as Taiwan and its surrounding islands, the Penghu Islands, the Dongsha Islands, the Xisha Islands, the Zhongsha Islands, the Nansha Islands and all other islands belonging to China which are separated from the mainland and its coastal islands by the high seas.[44]

China reaffirmed its claim of sovereignty over the Zhongsha Islands in its 1992 Law on the territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. China claims all the islands, reefs, and shoals within a U-shaped line in the South China Sea drawn in 1947 as its territory. Scarborough shoal lies within this area.[44]

China further asserted its claim shortly after the departure of the US Navy force from Subic, Zambales, Philippines. In the late 1970s, many scientific expedition activities organized by State Bureau of Surveying, National Earthquake Bureau and National Bureau of Oceanography were held in the shoal and around this area. In 1980, a stone marker reading "South China Sea Scientific Expedition" was installed on the South Rock, but was removed by Philippines in 1997.[26]

Claim by the Philippines

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mapa de las yslas Philipinas. |

The Philippines state that its assertion of sovereignty over the shoal is based on the juridical criteria established by public international law on the lawful methods for the acquisition of sovereignty. Among the criteria (effective occupation, cession, prescription, conquest, and accretion), the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) has asserted that the country exercised both effective occupation and effective jurisdiction over the shoal, which it terms Bajo de Masinloc, since its independence. Thus, it claims to have erected flags in some islands and a lighthouse which it reported to the International Maritime Organization. It also asserts that the Philippine and US Naval Forces have used it as impact range and that its Department of Environment and Natural Resources has conducted scientific, topographic and marine studies in the shoal, while Filipino fishermen regularly use it as fishing ground and have always considered it their own.[45]

The DFA also claims that the name Bajo de Masinloc (translated as "under Masinloc") itself identifies the shoal as a particular political subdivision of the Philippine Province of Zambales, known as Masinloc.[45] As basis, the Philippines cites the Island of Palmas Case, where the sovereignty of the island was adjudged by the international court in favor of the Netherlands because of its effective jurisdiction and control over the island despite the historic claim of Spain. Thus, the Philippines argues that the historic claim of China over the Scarborough Shoal still needs to be substantiated by a historic title, since a claim by itself is not among the internationally recognized legal basis for acquiring sovereignty over territory.

It also asserts that there is no indication that the international community has acquiesced to China's historical claim, and that the activity of fishing of private Chinese individuals, claimed to be a traditional exercise among these waters, does not constitute a sovereign act of the Chinese state.[46]

The Philippine government argues that since the legal basis of its claim is based on the international law on acquisition of sovereignty, the Exclusive Economic Zone claim on the waters around Scarborough is different from the sovereignty exercised by the Philippines in the shoal.[45][47]

The Philippine government has proposed taking the dispute to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) as provided in Part XV of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, but the Chinese government has rejected this, insisting on bilateral discussions.[48][49][50]

The Philippines also claims that as early as the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, Filipino fishermen were already using the area as a traditional fishing ground and shelter during bad weather.[51]

Several official Philippine maps published by Spain and United States in 18th and 20th centuries show Scarborough Shoal as Philippine territory. The 18th-century map "Carta hydrographica y chorographica de las Islas Filipinas" (1734) shows the Scarborough Shoal then was named as Panacot Shoal. The map also shows the shape of the shoal as consistent with the current maps available as today. In 1792, another map drawn by the Malaspina expedition and published in 1808 in Madrid, Spain also showed Bajo de Masinloc as part of Philippine territory. The map showed the route of the Malaspina expedition to and around the shoal. It was reproduced in the Atlas of the 1939 Philippine Census, which was published in Manila a year later and predates the controversial 1947 Chinese South China Sea Claim Map that shows no Chinese name on it.[52] Another topographic map drawn in 1820 shows the shoal, named there as "Bajo Scarburo," as a constituent part of Sambalez (Zambales province).[53] During the 1900s, Mapa General, Islas Filipinas, Observatorio de Manila, and US Coast and Geodetic Survey Map include the Scarborough Shoal named as "Baju De Masinloc."[54] A map published in 1978 by the Philippine National Mapping and Resource Information Authority, however, did not indicate Scarborough Shoal as part of the Philippines.[55] Scholar Li Xiao Cong stated in his published paper that Panacot Shoal is not Scarborough Shoal, in the 1778 map "A chart of the China Sea and Philippine Islands with the Archipelagos of Felicia and Soloo", Scarborough shoal and 3 other shoals Galit, Panacot and Lumbay were all shown independently. Li also pointed out that the three shoals were also shown on Chinese maps which were published in 1717.[56]

In 1957, the Philippine government conducted an oceanographic survey of the area and together with the US Navy force based in then U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay in Zambales, used the area as an impact range for defense purposes. An 8.3 meter high flag pole flying a Philippine flag was raised in 1965. An iron tower that was to serve as a small lighthouse was also built and operated the same year.[57][58] In 1992, the Philippine Navy rehabilitated the lighthouse and reported it to the International Maritime Organization for publication in the List of Lights. As of 2009, the military-maintained lighthouse is non-operational.[59]

Historically, the Philippine boundary has been defined by its 3 treaties,[60][61] Treaty of Paris (1898), Treaty of Washington (1900) and "Convention regarding the boundary between the Philippine Archipelago and the State of North Borneo". Many analysts consider that the 1900 Treaty of Washington concerned only the islands of Sibutu and Cagayan de Sulu.,[62][63] but a point of view argued that Scarborough Shoal has been transferred to the United States based on the Treaty of Washington (1900),[64] ignoring the fact that the cession documents from the United States to the Philippines did not have any reference to the Scarborough Shoal.[65]

The DFA asserts that the basis of Philippine sovereignty and jurisdiction over the rock features of Bajo de Masinloc are not premised on the cession by Spain of the Philippine archipelago to the United States under the Treaty of Paris, and argues that the matter that the rock features of Bajo de Masinloc are not included or within the limits of the Treaty of Paris as alleged by China is therefore immaterial and of no consequence.[45][47]

Presidential Decree No. 1596 issued on June 11, 1978 asserted that islands designated as the Kalayaan Island Group and comprising most of the Spratly Islands are subject to the sovereignty of the Philippines,[66] and by virtue of the Presidential Decree No. 1599 issued on June 11, 1978 claimed an Exclusive Economic Zone up to 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the baselines from which their territorial sea is measured.[67]

The Philippines' bilateral dispute with China over the shoal began on April 30, 1997 when Filipino naval ships prevented Chinese boats from approaching the shoal.[2] On June 5 of that year, Domingo Siazon, who was then the Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs, testified in front of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate that the Shoal was "a new issue on overlapping claims between the Philippines and China".[68]

In 2009, the Philippine Baselines Law of 2009 (RA 9522), authored and sponsored by Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago, was enacted into law. The new law classified the Kalayaan Island Group and the Scarborough Shoal as a regime of islands under the Republic of the Philippines.[3][69]

Permanent Court of Arbitration tribunal ruling

In January 2013 the Philippines formally initiated arbitration proceedings against the PRC claim on the territories within the "nine-dash line" that include Scarborough Shoal, which the Philippines claimed is unlawful under the UNCLOS convention.[70] An arbitration tribunal was constituted under Annex VII of UNCLOS and it was decided in July 2013 that the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) would function as registry and provide administrative duties in the proceedings.[71]

On 12 July 2016 the PCA tribunal agreed unanimously with the Philippines. In its award, it concluded that there is no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or resources, hence there was "no legal basis for China to claim historic rights" over the area within the nine-dash line.[72][73] The tribunal also judged that the PRC had caused "severe harm to the coral reef environment",[74] and that it had violated the Philippines' sovereign rights in its Exclusive Economic Zone by interfering with Philippine fishing and petroleum exploration by, for example, restricting the traditional fishing rights of Filipino fishermen at Scarborough Shoal.[75] The PRC rejected the ruling, calling it "ill-founded"". PRC paramount leader and Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping insisted that "China's territorial sovereignty and marine rights in the South China Sea will not be affected by the so-called Philippines South China Sea ruling in any way", nevertheless the PRC would still be "committed to resolving disputes" with its neighbours. China afterwards sent more warships in the Scarborough Shoal.[75][76]

See also

- China–Philippines relations

- List of territorial disputes

- South China Sea Islands

Other East Asian island disputes

- Okinotorishima, another smaller shoal with three skerries

- Kuril Islands dispute

- Liancourt Rocks dispute

- Paracel Islands

- Pratas Islands

- Senkaku Islands dispute

- Spratly Islands dispute

Notes

- Often considered one because the other skerry's area during high-tide is negligible.

References

- Aning, Jerome (May 5, 2012). "PH plane flies over Panatag Shoal". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Zou, Keyuan (1999). "Scarborough Reef: a new flashpoint in Sino-Philippine relations?" (PDF). IBRU Boundary & Security Bulletin, University of Durham. 7 (2): 11.

- "[ REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9522, March 10, 2009]". Philippine Supreme Court E-Library. March 12, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- "Counter-Coercion Series: Scarborough Shoal Standoff". Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. May 22, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Standoff in the South China Sea | YaleGlobal Online". yaleglobal.yale.edu. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Pazzibugan, Christine O. Avendaño, Dona Z. "Aquino, Dempsey tackle Scarborough Shoal standoff". globalnation.inquirer.net. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- The Hague (July 12, 2016). "PRESS RELEASE--The South China Sea Arbitration" (PDF). pca-cpa.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Courting trouble". The Economist. July 16, 2016. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- W. Gilbert (1804) A New Nautical Directory for the East-India and China Navigation .., pp.480=482.

- Joseph Huddart (1801). The Oriental Navigator, Or, New Directions for Sailing to and from the East Indies: Also for the Use of Ships Trading in the Indian and China Seas to New Holland, &c. &c. James Humphreys. p. 454.

- Arches II, Victor (April 28, 2012). "It belongs to China". Manila Standard Today.

- Tordesillas, Ellen (January 21, 2013). "Chinese 'occupation' of Bajo de Masinloc could reduce PH territorial waters by 38 percent". VERA Files. ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "Timeline: South China Sea dispute". Financial Times. July 12, 2016.

- Beech, Hannah (July 11, 2016). "China's Global Reputation Hinges on Upcoming South China Sea Court Decision". TIME.

- "Press Release: Arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People's Republic of China: Arbitral Tribunal Establishes Rules of Procedure and Initial Timetable". PCA. August 27, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "Press Release: The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People's Republic of China)" (PDF). PCA. July 12, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "A UN-appointed tribunal dismisses China's claims in the South China Sea". The Economist. July 12, 2016.

- Perez, Jane (July 12, 2016). "Beijing's South China Sea Claims Rejected by Hague Tribunal". The New York Times.

- Tom Phillips, Oliver Holmes, Owen Bowcott (July 12, 2016). "Beijing rejects tribunal's ruling in South China Sea case". The Guardian.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Chow, Jermyn (July 12, 2016). "Taiwan rejects South China Sea ruling, says will deploy another navy vessel to Taiping". The Straits Times.

- "South China Sea: Tribunal backs case against China brought by Philippines". BBC. July 12, 2016.

- Jun Mai, Shi Jiangtao (July 12, 2016). "Taiwan-controlled Taiping Island is a rock, says international court in South China Sea ruling". South China Morning Post.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Krishnamoorthy, Nandini (February 9, 2017). "South China Sea: Philippines sees Chinese attempt to build on reef near its coast". IBT International Business Times. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- Randy V. Datu. "'2 bottles of water for P3,000 worth of fish in Panatag Shoal'". Rappler. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Destruction of Scarborough Shoal seen on Google Earth". philstar.com. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Chen Ruobing 陈若冰 (April 21, 2012). 中国与菲律宾中沙黄岩岛之争 [The dispute between China and the Philippines over Zhongsha Huangyan Island] (in Chinese). Sohu News. Retrieved March 21, 2014. English translation of original Chinese text available here.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COMUSFACSUBICINST_3500.1A-20160223143520.pdf

- Li, Jiaxin (July 28, 2015). "Philippines Fishermen Remove Chinese Buoys". People's Daily. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- "Scarborough Contingency plan". www.amti.csis.org. CSIS maritime Transparency Initiative. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- Poling, Gregory; Cooper, Zack. "No reclamation so far on Scarborough Shoal". www.amti.csis.org. CSIS AMTI. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- Malakunas, Karl; Abbugao, Martin (September 8, 2016). "China under pressure at Asia summit over sea row". Yahoo News. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- Perlez, Jane (September 5, 2016). "New Chinese Vessels Seen Near Disputed Reef in South China Sea". NYT. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- "UPDATED: Imagery Suggests Philippine Fishermen Still Not Entering Scarborough Shoal". www.amti.csis.org. CSIS. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- Rosenberg, David, "Governing the South China Sea: From Freedom of the Seas to Ocean Enclosure Movements", Harvard Asia Quarterly/southchinasea.org, "2013/02".

- LUO, Zheng 罗铮; LÜ, Desheng 吕德胜 (May 10, 2012). "Six Irrefutable Proofs: Huangyan Island Belongs to China 六大铁证:黄岩岛属于中国 (in Chinese)". PLA Daily 解放军报. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012. See under "Irrefutable proof 1: China discovered the Huangyuan Island long time ago" 铁证一:中国早发现黄岩岛.

- HAN, Zhenhua 韩振华 (1979). "The South Sea as Chinese National Territory in the Yuan-Era 'Measurement of the Four Seas' 元代《四海测验》中的中国疆宇之南海 (in Chinese)". Research on the South China Sea 南海问题研究. 1979. Retrieved May 22, 2012. A rough English translation of this article can be found here.

- Foreign Ministry of the People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国外交部 (January 30, 1980), China's Sovereignty Over the Xisha and Zhongsha Islands is Indisputable 中国对西沙群岛和南沙群岛的主权无可争辩 (in Chinese), p. 6. This document claims that "the Nanhai measuring point was 'where the pole star rises at 15 [ancient Chinese] degrees [above the horizon]', which should correspond to 14.47 [modern] degrees; adding a margin of error of about 1 degree, its location falls precisely on today's Xisha Islands" (南海这个测点‘北极出地一十五度’应为北纬14度47分,加上一度左右的误差,其位置也正好在今西沙群岛), which shows that "the Xisha Islands were inside Chinese territory during the Yuan dynasty" (西沙群岛在元代是在中国的疆界之内).

- See for instance NIU, Zhongxun (1998). "Investigation on the Geographical Location of Nanhai in the Yuan-Dynasty Survey of the Four Seas 元代四海测验中南海观测站地理位置考辨". Research on the Historical Geography of China's Frontiers 中国边疆史地研究. 1998 (2)..

- ZENG, Zhaoxuan 曾昭旋 (1990), "The Yuan-Dynasty Survey of Nanhai was in Champa: Guo Shoujing Did not Go to the Zhongsha or Xisha to Measure Latitude 元代南海测验在林邑考--郭守敬未到西中沙测量纬度 (in Chinese)", Historical Research 历史研究, 1990 (5). Among other evidence, Zeng cites a Chinese geologist who argues that the Scarborough Shoal was still submerged under water during the Yuan dynasty.

- CHEN, Meidong 陈美东 (2003), Critical Biography of Guo Shoujing 郭守敬评传, Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, pp. 78 and 201–4.

- Sivin, Nathan (2009), Granting the Seasons: The Chinese Astronomical Reform of 1280, New York: Springer, pp. 577–79.

- Zou 2005, p. 63.

- Zou 2005, p. 62.

- Zou 2005, p. 64.

- Philippine Position on Bajo de Masinloc and the Waters Within its Vicinity (18 April 2012), The Department of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of the Philippines.

- "Philippine Position on Bajo de Masinloc and the Waters Within its Vicinity". April 18, 2012.

- PH sovereignty based on Unclos, principles of international law (20 April 2012), The Department of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of the Philippines (as reported by globalnation.inquirer.net).

- "China deploys gunboat". Philippine Daily Inquirer. April 20, 2012.

- Fr. Joaquin G. Bernas S. J. (April 22, 2012). "Scarborough Shoal". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- PART XV : SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTES, UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA : AGREEMENT RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PART XI OF THE CONVENTION, The United Nations.

- Zou 2005, pp. 64–65.

- "The Manila Times - Trusted Since 1898". The Manila Times.

- "Scarborough belongs to PH, old maps show". Philippine Daily Inquirer. April 23, 2012.

- "In a Troubled Sea: Reed Bank, Kalayaan, Lumbay, Galit, and Panacot". Yahoo News Philippines. March 28, 2011. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013.

- Zou 2005, p. 58

- "从古地图看黄岩岛的归属" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "In The Know: The Scarborough Shoal". Philippine Daily Inquirer. April 12, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- What’s become of the MMDA?, Philippine Star, 2 April 2008

- COAST GUARD DISTRICT NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION - CENTRAL LUZON LIGHTSTATIONS (archived from the original on 2010-01-16)

- Bautista, Lowell (2009). "The Philippine Treaty Limits and Territorial Water Claim in International Law". ro.uow.edu.au. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Backgrounder: Facts about Philippines' illegal occupation of China's Nansha Islands - Xinhua | English.news.cn

- François-Xavier Bonnet. "Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal" (pdf): 12.

Many analysts consider, in a restrictive manner, that this treaty concerned only the islands of Sibutu and Cagayan de Sulu. In fact, the unique article of this treaty is open to all islands that belonged to the Philippines during the Spanish time but would be found, in the future, outside the limits of the Treaty of Paris. Among them were the two islands cited above.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Joaquin G. Bernas (January 1, 1995). Foreign Relations in Constitutional Law. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-971-23-1903-7.

- "Maritime affairs expert separates facts from fiction on Scarborough Shoal". Philippine Daily Inquirer. October 6, 2014.

- Bautista, Lowell B. (2008). "The Historical Context and Legal Basis of the Philippine Treaty Limits" (PDF). blog.hawaii.edu. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "PRESIDENTIAL DECREE NO. 1596 - DECLARING CERTAIN AREA PART OF THE PHILIPPINE TERRITORY AND PROVIDING FOR THEIR GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION". Chan Robles Law Library. June 11, 1978.

- "PRESIDENTIAL DECREE No. 1599 ESTABLISHING AN EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES". Chan Robles Law Library. June 11, 1978.

- Zou, Keyuan (2005). Law of the Sea in East Asia: Issues And Prospects. Psychology Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-415-35074-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Philippine Baselines Law of 2009 (March 11, 2009), GMA News.

- "Timeline: South China Sea dispute". Financial Times. July 12, 2016.

- "Press Release: Arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People's Republic of China: Arbitral Tribunal Establishes Rules of Procedure and Initial Timetable". PCA. August 27, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "Press Release: The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People's Republic of China)" (PDF). PCA. July 12, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "A UN-appointed tribunal dismisses China's claims in the South China Sea". The Economist. July 12, 2016.

- Perez, Jane (July 12, 2016). "Beijing's South China Sea Claims Rejected by Hague Tribunal". The New York Times.

- Tom Phillips, Oliver Holmes, Owen Bowcott (July 12, 2016). "Beijing rejects tribunal's ruling in South China Sea case". The Guardian.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "South China Sea: Tribunal backs case against China brought by Philippines". BBC. July 12, 2016.

Further reading

- Bautista, Lowell B. (December 2011). "PHILIPPINE TERRITORIAL BOUNDARIES: INTERNAL TENSIONS, COLONIAL BAGGAGE, AMBIVALENT CONFORMITY" (PDF). JATI - Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 16: 35–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 30, 2013.

- Bautista, Lowell B. (February 2012). "The Implications of Recent Decisions on the Territorial and Maritime Boundary Disputes in East and Southeast Asia". maritime energy resources in asia : Legal Regimes and Cooperation : NBR Special Report #37. Academia.edu.

- Bautista, Lowell B. (January 1, 2010). "The Legal Status of the Philippine Treaty Limits In International Law". Academia.edu. doi:10.1007/s12180-009-0003-5. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bautista, Lowell B. (Fall 2009). "The Historical Background, Geographical Extent and Legal Bases of the Philippine Territorial Water Claim". The Journal of Comparative Asian Development. 8 (2).

- Bonnet, Francois-Xavier "Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal" Irasec's Discussion Papers, No 14, November 2012, Irasec.com

- Tupaz, Edsel. "Sidebar Brief: The Law of the Seas and the Scarborough Shoal Dispute". Jurist.

- AFP (September 11, 2013). "Philippines mulls removing 'Chinese' blocks at shoal". Google Philippines. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- Hayton, B. (2014). The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia. Yale University Press. Retrieved August 7, 2018.