Resource Description Framework

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a family of World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) specifications[1] originally designed as a metadata data model. It has come to be used as a general method for conceptual description or modeling of information that is implemented in web resources, using a variety of syntax notations and data serialization formats. It is also used in knowledge management applications.

| Status | Published, W3C Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Year started | 1996 |

| Editors | Richard Cyganiak, David Wood, Markus Lanthaler |

| Base standards | URI |

| Related standards | RDFS, OWL, RIF, RDFa |

| Domain | Semantic Web |

| Abbreviation | RDF |

| Website | www |

RDF was adopted as a W3C recommendation in 1999. The RDF 1.0 specification was published in 2004, the RDF 1.1 specification in 2014.

Overview

The RDF data model[2] is similar to classical conceptual modeling approaches (such as entity–relationship or class diagrams). It is based on the idea of making statements about resources (in particular web resources) in expressions of the form subject–predicate–object, known as triples. The subject denotes the resource, and the predicate denotes traits or aspects of the resource, and expresses a relationship between the subject and the object.

For example, one way to represent the notion "The sky has the color blue" in RDF is as the triple: a subject denoting "the sky", a predicate denoting "has the color", and an object denoting "blue". Therefore, RDF uses subject instead of object (or entity) in contrast to the typical approach of an entity–attribute–value model in object-oriented design: entity (sky), attribute (color), and value (blue).

RDF is an abstract model with several serialization formats (i.e. file formats), so the particular encoding for resources or triples varies from format to format.

This mechanism for describing resources is a major component in the W3C's Semantic Web activity: an evolutionary stage of the World Wide Web in which automated software can store, exchange, and use machine-readable information distributed throughout the Web, in turn enabling users to deal with the information with greater efficiency and certainty. RDF's simple data model and ability to model disparate, abstract concepts has also led to its increasing use in knowledge management applications unrelated to Semantic Web activity.

A collection of RDF statements intrinsically represents a labeled, directed multi-graph. This in theory makes an RDF data model better suited to certain kinds of knowledge representation than are other relational or ontological models. However, in practice, RDF data is often stored in relational database or native representations (also called Triplestores—or Quad stores, if context such as the named graph is also stored for each RDF triple).[3]

As RDFS and OWL demonstrate, one can build additional ontology languages upon RDF.

History

The initial RDF design, intended to "build a vendor-neutral and operating system-independent system of metadata,"[4] derived from the W3C's Platform for Internet Content Selection (PICS), an early web content labelling system,[5] but the project was also shaped by ideas from Dublin Core, and from the Meta Content Framework (MCF),[4] which had been developed during 1995–1997 by Ramanathan V. Guha at Apple and Tim Bray at Netscape.[6]

A first public draft of RDF appeared in October 1997,[7][8] issued by a W3C working group that included representatives from IBM, Microsoft, Netscape, Nokia, Reuters, SoftQuad, and the University of Michigan.[5]

In 1999, the W3C published the first recommended RDF specification, the Model and Syntax Specification ("RDF M&S").[9] This described RDF's data model and an XML serialization.[10]

Two persistent misunderstandings about RDF developed at this time: firstly, due to the MCF influence and the RDF "Resource Description" initialism, the idea that RDF was specifically for use in representing metadata; secondly that RDF was an XML format rather than a data model, and only the RDF/XML serialisation being XML-based. RDF saw little take-up in this period, but there was significant work done in Bristol, around ILRT at Bristol University and HP Labs, and in Boston at MIT. RSS 1.0 and FOAF became exemplar applications for RDF in this period.

The recommendation of 1999 was replaced in 2004 by a set of six specifications:[11] "The RDF Primer",[12] "RDF Concepts and Abstract",[13] "RDF/XML Syntax Specification (revised)",[14] "RDF Semantics",[15] "RDF Vocabulary Description Language 1.0",[16] and "The RDF Test Cases".[17]

This series was superseded in 2014 by the following six "RDF 1.1" documents: "RDF 1.1 Primer,"[18] "RDF 1.1 Concepts and Abstract Syntax,"[19] "RDF 1.1 XML Syntax,"[20] "RDF 1.1 Semantics,"[21] "RDF Schema 1.1,"[22] and "RDF 1.1 Test Cases".[23]

RDF topics

Vocabulary

The vocabulary defined by the RDF specification is as follows:[24]

Classes

rdf

rdf:XMLLiteral– the class of XML literal valuesrdf:Property– the class of propertiesrdf:Statement– the class of RDF statementsrdf:Alt,rdf:Bag,rdf:Seq– containers of alternatives, unordered containers, and ordered containers (rdfs:Containeris a super-class of the three)rdf:List– the class of RDF Listsrdf:nil– an instance ofrdf:Listrepresenting the empty list

rdfs

rdfs:Resource– the class resource, everythingrdfs:Literal– the class of literal values, e.g. strings and integersrdfs:Class– the class of classesrdfs:Datatype– the class of RDF datatypesrdfs:Container– the class of RDF containersrdfs:ContainerMembershipProperty– the class of container membership properties,rdf:_1,rdf:_2, ..., all of which are sub-properties ofrdfs:member

Properties

rdf

rdf:type– an instance ofrdf:Propertyused to state that a resource is an instance of a classrdf:first– the first item in the subject RDF listrdf:rest– the rest of the subject RDF list afterrdf:firstrdf:value– idiomatic property used for structured valuesrdf:subject– the subject of the RDF statementrdf:predicate– the predicate of the RDF statementrdf:object– the object of the RDF statement

rdf:Statement, rdf:subject, rdf:predicate, rdf:object are used for reification (see below).

rdfs

rdfs:subClassOf– the subject is a subclass of a classrdfs:subPropertyOf– the subject is a subproperty of a propertyrdfs:domain– a domain of the subject propertyrdfs:range– a range of the subject propertyrdfs:label– a human-readable name for the subjectrdfs:comment– a description of the subject resourcerdfs:member– a member of the subject resourcerdfs:seeAlso– further information about the subject resourcerdfs:isDefinedBy– the definition of the subject resource

This vocabulary is used as a foundation for RDF Schema, where it is extended.

Serialization formats

| Filename extension | .ttl |

|---|---|

| Internet media type | text/turtle[25] |

| Developed by | World Wide Web Consortium |

| Standard | RDF 1.1 Turtle: Terse RDF Triple Language January 9, 2014 |

| Open format? | Yes |

| |

| Filename extension | .rdf |

|---|---|

| Internet media type | application/rdf+xml[26] |

| Developed by | World Wide Web Consortium |

| Standard | Concepts and Abstract Syntax February 10, 2004 |

| Open format? | Yes |

Several common serialization formats are in use, including:

- Turtle,[27] a compact, human-friendly format.

- N-Triples,[28] a very simple, easy-to-parse, line-based format that is not as compact as Turtle.

- N-Quads,[29][30] a superset of N-Triples, for serializing multiple RDF graphs.

- JSON-LD,[31] a JSON-based serialization.

- N3 or Notation3, a non-standard serialization that is very similar to Turtle, but has some additional features, such as the ability to define inference rules.

- RDF/XML,[32] an XML-based syntax that was the first standard format for serializing RDF.

- RDF/JSON,[33] an alternative syntax for expressing RDF triples using a simple JSON notation.

RDF/XML is sometimes misleadingly called simply RDF because it was introduced among the other W3C specifications defining RDF and it was historically the first W3C standard RDF serialization format. However, it is important to distinguish the RDF/XML format from the abstract RDF model itself. Although the RDF/XML format is still in use, other RDF serializations are now preferred by many RDF users, both because they are more human-friendly,[34] and because some RDF graphs are not representable in RDF/XML due to restrictions on the syntax of XML QNames.

With a little effort, virtually any arbitrary XML may also be interpreted as RDF using GRDDL (pronounced 'griddle'), Gleaning Resource Descriptions from Dialects of Languages.

RDF triples may be stored in a type of database called a triplestore.

Resource identification

The subject of an RDF statement is either a uniform resource identifier (URI) or a blank node, both of which denote resources. Resources indicated by blank nodes are called anonymous resources. They are not directly identifiable from the RDF statement. The predicate is a URI which also indicates a resource, representing a relationship. The object is a URI, blank node or a Unicode string literal. As of RDF 1.1 resources are identified by IRI's. IRI is a generalization of URI.[35]

In Semantic Web applications, and in relatively popular applications of RDF like RSS and FOAF (Friend of a Friend), resources tend to be represented by URIs that intentionally denote, and can be used to access, actual data on the World Wide Web. But RDF, in general, is not limited to the description of Internet-based resources. In fact, the URI that names a resource does not have to be dereferenceable at all. For example, a URI that begins with "http:" and is used as the subject of an RDF statement does not necessarily have to represent a resource that is accessible via HTTP, nor does it need to represent a tangible, network-accessible resource — such a URI could represent absolutely anything. However, there is broad agreement that a bare URI (without a # symbol) which returns a 300-level coded response when used in an HTTP GET request should be treated as denoting the internet resource that it succeeds in accessing.

Therefore, producers and consumers of RDF statements must agree on the semantics of resource identifiers. Such agreement is not inherent to RDF itself, although there are some controlled vocabularies in common use, such as Dublin Core Metadata, which is partially mapped to a URI space for use in RDF. The intent of publishing RDF-based ontologies on the Web is often to establish, or circumscribe, the intended meanings of the resource identifiers used to express data in RDF. For example, the URI:

http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-owl-guide-20040210/wine#Merlot

is intended by its owners to refer to the class of all Merlot red wines by vintner (i.e., instances of the above URI each represent the class of all wine produced by a single vintner), a definition which is expressed by the OWL ontology — itself an RDF document — in which it occurs. Without careful analysis of the definition, one might erroneously conclude that an instance of the above URI was something physical, instead of a type of wine.

Note that this is not a 'bare' resource identifier, but is rather a URI reference, containing the '#' character and ending with a fragment identifier.

Statement reification and context

The body of knowledge modeled by a collection of statements may be subjected to reification, in which each statement (that is each triple subject-predicate-object altogether) is assigned a URI and treated as a resource about which additional statements can be made, as in "Jane says that John is the author of document X". Reification is sometimes important in order to deduce a level of confidence or degree of usefulness for each statement.

In a reified RDF database, each original statement, being a resource, itself, most likely has at least three additional statements made about it: one to assert that its subject is some resource, one to assert that its predicate is some resource, and one to assert that its object is some resource or literal. More statements about the original statement may also exist, depending on the application's needs.

Borrowing from concepts available in logic (and as illustrated in graphical notations such as conceptual graphs and topic maps), some RDF model implementations acknowledge that it is sometimes useful to group statements according to different criteria, called situations, contexts, or scopes, as discussed in articles by RDF specification co-editor Graham Klyne.[36][37] For example, a statement can be associated with a context, named by a URI, in order to assert an "is true in" relationship. As another example, it is sometimes convenient to group statements by their source, which can be identified by a URI, such as the URI of a particular RDF/XML document. Then, when updates are made to the source, corresponding statements can be changed in the model, as well.

Implementation of scopes does not necessarily require fully reified statements. Some implementations allow a single scope identifier to be associated with a statement that has not been assigned a URI, itself.[38][39] Likewise named graphs in which a set of triples is named by a URI can represent context without the need to reify the triples.[40]

Query and inference languages

The predominant query language for RDF graphs is SPARQL. SPARQL is an SQL-like language, and a recommendation of the W3C as of January 15, 2008.

The following is an example of a SPARQL query to show country capitals in Africa, using a fictional ontology:

PREFIX ex: <http://example.com/exampleOntology#>

SELECT ?capital ?country

WHERE {

?x ex:cityname ?capital ;

ex:isCapitalOf ?y .

?y ex:countryname ?country ;

ex:isInContinent ex:Africa .

}

Other non-standard ways to query RDF graphs include:

- RDQL, precursor to SPARQL, SQL-like

- Versa, compact syntax (non–SQL-like), solely implemented in 4Suite (Python).

- RQL, one of the first declarative languages for uniformly querying RDF schemas and resource descriptions, implemented in RDFSuite.[41]

- SeRQL, part of Sesame

- XUL has a template element in which to declare rules for matching data in RDF. XUL uses RDF extensively for databinding.

Validation and description

There are several proposals to validate and describe RDF:

- SPARQL Inferencing Notation (SPIN) [42] was based on SPARQL queries. It has been effectively deprecated in favor of SHACL.[43]

- SHACL (Shapes Constraint Language) [44] is expresses constraints on RDF Graphs. SHACL is divided in two parts: SHACL Core and SHACL-SPARQL. SHACL Core consists of a list of built-in constraints such as cardinality, range of values and many others. SHACL-SPARQL consists of all features of SHACL Core plus the advanced features of SPARQL-based constraints and an extension mechanism to declare new constraint components.

- ShEx (Shape Expressions) [45] is a concise language for RDF validation and description.

Examples

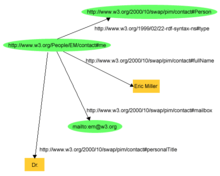

Example 1: Description of a person named Eric Miller[46]

The following example is taken from the W3C website[46] describing a resource with statements "there is a Person identified by http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me, whose name is Eric Miller, whose email address is e.miller123(at)example (changed for security purposes), and whose title is Dr.

The resource "http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me" is the subject.

The objects are:

- "Eric Miller" (with a predicate "whose name is"),

- mailto:e.miller123(at)example (with a predicate "whose email address is"), and

- "Dr." (with a predicate "whose title is").

The subject is a URI.

The predicates also have URIs. For example, the URI for each predicate:

- "whose name is" is http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#fullName,

- "whose email address is" is http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#mailbox,

- "whose title is" is http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#personalTitle.

In addition, the subject has a type (with URI http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type), which is person (with URI http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#Person).

Therefore, the following "subject, predicate, object" RDF triples can be expressed:

- http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me, http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#fullName, "Eric Miller"

- http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me, http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#mailbox, mailto:e.miller123(at)example

- http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me, http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#personalTitle, "Dr."

- http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me, http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type, http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#Person

In standard N-Triples format, this RDF can be written as:

<http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me> <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#fullName> "Eric Miller" .

<http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me> <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#mailbox> <mailto:e.miller123(at)example> .

<http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me> <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#personalTitle> "Dr." .

<http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me> <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#Person> .

Equivalently, it can be written in standard Turtle (syntax) format as:

@prefix eric: <http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#> .

@prefix contact: <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#> .

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

eric:me contact:fullName "Eric Miller" .

eric:me contact:mailbox <mailto:e.miller123(at)example> .

eric:me contact:personalTitle "Dr." .

eric:me rdf:type contact:Person .

Or, it can be written in RDF/XML format as:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<rdf:RDF xmlns:contact="http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#" xmlns:eric="http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#" xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me">

<contact:fullName>Eric Miller</contact:fullName>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me">

<contact:mailbox rdf:resource="mailto:e.miller123(at)example"/>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me">

<contact:personalTitle>Dr.</contact:personalTitle>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/People/EM/contact#me">

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#Person"/>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

Example 2: The postal abbreviation for New York

Certain concepts in RDF are taken from logic and linguistics, where subject-predicate and subject-predicate-object structures have meanings similar to, yet distinct from, the uses of those terms in RDF. This example demonstrates:

In the English language statement 'New York has the postal abbreviation NY' , 'New York' would be the subject, 'has the postal abbreviation' the predicate and 'NY' the object.

Encoded as an RDF triple, the subject and predicate would have to be resources named by URIs. The object could be a resource or literal element. For example, in the N-Triples form of RDF, the statement might look like:

<urn:x-states:New%20York> <http://purl.org/dc/terms/alternative> "NY" .

In this example, "urn:x-states:New%20York" is the URI for a resource that denotes the US state New York, "http://purl.org/dc/terms/alternative" is the URI for a predicate (whose human-readable definition can be found at here [47]), and "NY" is a literal string. Note that the URIs chosen here are not standard, and don't need to be, as long as their meaning is known to whatever is reading them.

Example 3: A Wikipedia article about Tony Benn

In a like manner, given that "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Benn" identifies a particular resource (regardless of whether that URI could be traversed as a hyperlink, or whether the resource is actually the Wikipedia article about Tony Benn), to say that the title of this resource is "Tony Benn" and its publisher is "Wikipedia" would be two assertions that could be expressed as valid RDF statements. In the N-Triples form of RDF, these statements might look like the following:

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Benn> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title> "Tony Benn" .

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Benn> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/publisher> "Wikipedia" .

To an English-speaking person, the same information could be represented simply as:

The title of this resource, which is published by Wikipedia, is 'Tony Benn'

However, RDF puts the information in a formal way that a machine can understand. The purpose of RDF is to provide an encoding and interpretation mechanism so that resources can be described in a way that particular software can understand it; in other words, so that software can access and use information that it otherwise couldn't use.

Both versions of the statements above are wordy because one requirement for an RDF resource (as a subject or a predicate) is that it be unique. The subject resource must be unique in an attempt to pinpoint the exact resource being described. The predicate needs to be unique in order to reduce the chance that the idea of Title or Publisher will be ambiguous to software working with the description. If the software recognizes http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title (a specific definition for the concept of a title established by the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative), it will also know that this title is different from a land title or an honorary title or just the letters t-i-t-l-e put together.

The following example, written in Turtle, shows how such simple claims can be elaborated on, by combining multiple RDF vocabularies. Here, we note that the primary topic of the Wikipedia page is a "Person" whose name is "Tony Benn":

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

@prefix dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> .

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Benn>

dc:publisher "Wikipedia" ;

dc:title "Tony Benn" ;

foaf:primaryTopic [

a foaf:Person ;

foaf:name "Tony Benn"

] .

Applications

- DBpedia – Extracts facts from Wikipedia articles and publishes them as RDF data.

- YAGO – Similar to DBpedia extracts facts from Wikipedia articles and publishes them as RDF data.

- Wikidata – Collaboratively edited knowledge base hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation.

- Creative Commons – Uses RDF to embed license information in web pages and mp3 files.

- FOAF (Friend of a Friend) – designed to describe people, their interests and interconnections.

- Haystack client – Semantic web browser from MIT CS & AI lab.[48]

- IDEAS Group – developing a formal 4D ontology for Enterprise Architecture using RDF as the encoding.[49]

- Microsoft shipped a product, Connected Services Framework,[50] which provides RDF-based Profile Management capabilities.

- MusicBrainz – Publishes information about Music Albums.[51]

- NEPOMUK, an open-source software specification for a Social Semantic desktop uses RDF as a storage format for collected metadata. NEPOMUK is mostly known because of its integration into the KDE SC 4 desktop environment.

- Cochrane is a global publisher of clinical study meta-analyses in evidence based healthcare. They use an ontology driven data architecture to semantically annotate their published reviews with RDF based structured data.[52]

- RDF Site Summary – one of several "RSS" languages for publishing information about updates made to a web page; it is often used for disseminating news article summaries and sharing weblog content.

- Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) – a KR representation intended to support vocabulary/thesaurus applications

- SIOC (Semantically-Interlinked Online Communities) – designed to describe online communities and to create connections between Internet-based discussions from message boards, weblogs and mailing lists.[53]

- Smart-M3 – provides an infrastructure for using RDF and specifically uses the ontology agnostic nature of RDF to enable heterogeneous mashing-up of information[54]

- LV2 - a libre plugin format using Turtle to describe API/ABI capabilities and properties [55]

Some uses of RDF include research into social networking. It will also help people in business fields understand better their relationships with members of industries that could be of use for product placement.[56] It will also help scientists understand how people are connected to one another.

RDF is being used to have a better understanding of road traffic patterns. This is because the information regarding traffic patterns is on different websites, and RDF is used to integrate information from different sources on the web. Before, the common methodology was using keyword searching, but this method is problematic because it does not consider synonyms. This is why ontologies are useful in this situation. But one of the issues that comes up when trying to efficiently study traffic is that to fully understand traffic, concepts related to people, streets, and roads must be well understood. Since these are human concepts, they require the addition of fuzzy logic. This is because values that are useful when describing roads, like slipperiness, are not precise concepts and cannot be measured. This would imply that the best solution would incorporate both fuzzy logic and ontology.[57]

See also

- Notations for RDF

- TRiG

- TRiX

- RDF/XML

- RDFa

- JSON-LD

- Notation3

- Similar concepts

- Entity–attribute–value model

- Graph theory – an RDF model is a labeled, directed multi-graph.

- Website Parse Template

- Tagging

- SciCrunch

- Semantic network

- Other (unsorted)

- Semantic technology

- Associative model of data

- Business Intelligence 2.0 (BI 2.0)

- Data portability

- EU Open Data Portal

- Folksonomy

- Life Science Identifiers

- Swoogle

- Universal Networking Language (UNL)

- VoID

References

Citations

- "XML and Semantic Web W3C Standards Timeline" (PDF). 2012-02-04.

- "Resource Description Framework (RDF) Model and Syntax Specification". www.w3.org.

- Optimized Index Structures for Querying RDF from the Web Andreas Harth, Stefan Decker, 3rd Latin American Web Congress, Buenos Aires, Argentina, October 31 to November 2, 2005, pp. 71–80

- "World Wide Web Consortium Publishes Public Draft of Resource Description Framework". W3C. Cambridge, MA. 1997-10-03.

- Lash, Alex (1997-10-03). "W3C takes first step toward RDF spec". CNET News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- Hammersley, Ben (2005). Developing Feeds with RSS and Atom. Sebastopol: O’Reilly. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-596-00881-9.

- Lassila, Ora; Swick, Ralph R. (1997-10-02). "Resource Description Framework (RDF): Model and Syntax". W3C. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Swick, Ralph (1997-12-11). "Resource Description Framework (RDF)". W3C. Archived from the original on February 14, 1998. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Powers 2003, p. 2.

- "Resource Description Framework (RDF) Model and Syntax Specification". 22 Feb 1999. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Powers 2003, p. 3.

- Manola, Frank; Miller, Eric (2004-02-10), RDF Primer, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-21

- Klyne, Graham; Carroll, Jeremy J. (2004-02-10), Resource Description Framework (RDF): Concepts and Abstract Syntax, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-21

- Beckett, Dave (2004-02-10), RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised), W3C, retrieved 2015-11-21

- Hayes, Patrick (2014-02-10), RDF Semantics, retrieved 2015-11-21

- Brickley, Dan; Guha, R.V. (2004-02-10), RDF Vocabulary Description Language 1.0: RDF Schema: W3C Recommendation 10 February 2004, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-21

- Grant, Jan; Beckett, Dave (2004-02-10), RDF Test Cases, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-21

- Schreiber, Guus; Raimond, Yves (2014-06-24), RDF 1.1 Primer, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-22

- Cyganiak, Richard; Wood, David; Lanthaler, Markus (2014-02-25), RDF 1.1 Concepts and Abstract Syntax, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-22

- Gandon, Fabien; Schreiber, Guus (2014-02-25), RDF 1.1 XML Syntax, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-22

- Hayes, Patrick J.; Patel-Schneider, Peter F. (2014-02-25), RDF 1.1 Semantics, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-22

- Brickley, Dan; Guha, R.V. (2014-02-25), RDF Schema 1.1, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-22

- Kellogg, Gregg; Lanthaler, Markus (2014-02-25), RDF 1.1 Test Cases, W3C, retrieved 2015-11-22

- "RDF Vocabulary Description Language 1.0: RDF Schema". W3C. 2004-02-10. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- "RDF 1.1 Turtle: Terse RDF Triple Language". W3C. 9 Jan 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- "application/rdf+xml Media Type Registration". IETF. September 2004. p. 2. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- "RDF 1.1 Turtle: Terse RDF Triple Language". W3C. 9 January 2014.

- "RDF 1.1 N-Triples: A line-based syntax for an RDF graph". W3C. 9 January 2014.

- "N-Quads: Extending N-Triples with Context". 2012-06-25. Archived from the original on 2013-04-26.

- "RDF 1.1 N-Quads". W3C. January 2014.

- "JSON-LD 1.0: A JSON-based Serialization for Linked Data". W3C.

- "RDF 1.1 XML Syntax". W3C. 25 February 2014.

- "RDF 1.1 JSON Alternate Serialization (RDF/JSON)". W3C. 7 November 2013.

- "Problems of the RDF syntax". Vuk Miličić.

- RDF 1.1 Concepts and Abstract Syntax https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf11-concepts/

- Klyne, Graham. "Contexts for Information Modelling in RDF". www.ninebynine.org.

- "RDF Contexts - provenance and partial knowledge". www.ninebynine.org.

- "The Concept of 4Suite RDF Scopes". ogbuji.net.

- "Redland Notes - Contexts". librdf.org.

- "Named Graphs / Semantic Web Interest Group". www.w3.org.

- "The RDF Query Language (RQL)". The ICS-FORTH RDFSuite. ICS-FORTH.

- SPIN website

- Comparison of SHACL with SPIN

- SHACL Specification

- ShEx Specification

- "RDF Primer". W3C. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- DCMI Metadata Terms. Dublincore.org. Retrieved on 2014-05-30.

- "Haystack Group @ MIT CSAIL". groups.csail.mit.edu.

- "IDEAS Group". www.ideasgroup.org.

- "Connected Services Framework". microsoft.com.

- "LinkedBrainz/RDF - MusicBrainz Wiki". wiki.musicbrainz.org.

- "How knowledge graph technology is helping Cochrane respond to COVID-19". datalanguage.com.

- "SIOC Project". sioc-project.org.

- Oliver Ian, Honkola Jukka, Ziegler Jurgen (2008). “Dynamic, Localized Space Based Semantic Webs”. IADIS WWW/Internet 2008. Proceedings, p.426, IADIS Press, ISBN 978-972-8924-68-3

- "LV2 core specification". gitlab.com.

- An RDF Approach for Discovering the Relevant Semantic Associations in a Social Network By Thushar A.K, and P. Santhi Thilagam

- Traffic Information Retrieval Based on Fuzzy Ontology and RDF on the Semantic Web By Jun Zhai, Yi Yu, Yiduo Liang, and Jiatao Jiang (2008)

Sources

- Powers, Shelley (2003). Practical RDF. O'Reilly.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- W3C's RDF at W3C: specifications, guides, and resources

- RDF Semantics: specification of semantics, and complete systems of inference rules for both RDF and RDFS

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Resource Description Framework. |