Qibla

The qibla (Arabic: قِبْلَة, romanized: qiblat, "direction", transliterations include qiblah, qibleh, kiblah, kıble, kibla, or kiblat) is the direction used by Muslims in various religious contexts, including the salah or ritual prayer. The qibla is the direction of the building of Ka'bah in the Sacred Mosque, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, which Muslims believe to be a sacred site built by the prophets Abraham and Ishmael. According to the Islamic belief, this direction was ordained by God in the Quran, in chapter Al-Baqarah verses 144, 149, and 150, revealed to Muhammad in the second Hijri year; prior to this revelation Muhammad and his followers in Medina faced Jerusalem for prayers. Other than for the ritual prayer, it is also the direction for entering the state of ihram for the hajj pilgrimage, where animals are turned to in an Islamic slaughter, for the dead when buried, the recommended direction to make supplications, and the avoided direction when relieving nature and spitting. Most mosque contains a mihrab or a wall niche indicating the direction of the qibla. In practice, there are two manners of observing the qibla: ayn al-ka'bah which faces the Ka'ba exactly, and jihat al-ka'bah which faces only its general direction. Most Islamic authorities believe that the more precise ayn al-ka'bah is only required when possible (for example, inside the Sacred Mosque or in its surroundings), and otherwise jihat al-ka'bah can be used.

The most common technical definition used by Muslim astronomers is the direction shown by the great circle—in the Earth's sphere—passing through the Ka'bah and one's location. This direction shows the shortest possible path from one's place to Ka'bah, and allows for the exact calculation (hisab) of the qibla using a spherical trigonometric formula taking the coordinates of one's place and the Ka'bah as inputs. The method is applied to develop mobile applications and websites for Muslims, and to compile qibla tables used in instruments such as the qibla compass. In addition, the qibla can also be determined by observing the shadow of a vertical rod at or around two times of the year when the sun is directly overhead in Mecca—on 28 May at 12:18 Saudi Arabia Standard Time or 9:18 UTC and on 16 July at 12:27 SAST/9:27 UTC).

Before the development of astronomy in the Islamic world, Muslims used traditional methods to determine the qibla; these includes following the customs of the companions of the Prophet in one's place, using the setting and rising points of celestial objects, the direction of the wind, or using due south—Muhammad's qibla in Medina—everywhere. Early Islamic astronomy were built on its Indian and Greek counterparts—especially the works of Ptolemy, and soon Muslim astronomers developed methods to calculate approximate directions of the qibla, starting from mid-9th century. In the late 9th century and in the 10th century, Muslim astronomers developed methods to find the exact direction of the qibla that are equivalent to the modern formula. Initially, this "qibla of the astronomers" were used alongside various traditionally determined qiblas, resulting in a diversity of qiblas in medieval Muslim cities. In addition, the accurate geographic data necessary for the astronomical methods to yield an accurate result were only available in the 18th and 19th centuries, resulting in further diversity of the qibla. Historical mosques with differing qiblas still stand today throughout the Islamic world. The spaceflight of a devout Muslim Sheikh Muszaphar Shukor to the International Space Station on October 2007 generated a discussion with regards to qibla from the outer space. On Sheikh Muszaphar's request, the Islamic authority of his home country Malaysia issued a detailed guidance, suggesting a determination "based on what is possible" for the astronaut, in line with recommendations from other Islamic scholars.

Location

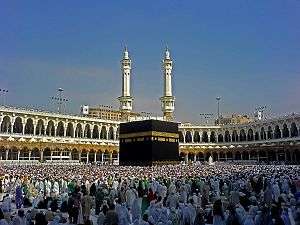

The qibla is the direction of the Ka'bah, a cube-like building at the centre of the Sacred Mosque (al-Masjid al-Haram) in Mecca, in the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia. Other than its role as qibla, it is a sacred site for Muslims, known as the House of God (Bait Allah) and where the tawaf is performed during the hajj and umra pilgrimages. The Ka'bah has an approximately rectangular ground plan with its four corners pointing close to the four cardinal directions.[1] According to the Quran, it was built by Abraham and Ishmael—both are prophets in Islam.[2] Not much historical records remain about the history of the Ka'bah prior to the rise of Islam, but in the generations before Muhammad, the building had been used as a shrine of the pre-Islamic Arabic religion.[2]

The religious status of Ka'bah (or the Sacred Mosque in which it is located) as the qibla is based on the verses 144, 149, and 150 of the Quran's chapter of al-Baqarah, each of which contains a command to "turn your face toward the Sacred Mosque" (fawalli wajhaka shatr al-Masjid il-Haram).[3] According to the Islamic tradition, these verses were revealed on the month of Rajab or Shaban on the second Hijri year (624 CE), or about 15 or 16 months after Muhammad's migration to Medina.[4][5] Prior to these revelations, Muhammad and the Muslims in Medina had prayed toward Jerusalem as qibla, the same direction used by the Jews of Medina for their prayers. Islamic traditions say that these verses were revealed during a prayer congregation; Muhammad and his followers immediately turned their directions from Jerusalem to Mecca in the middle of the prayer ritual. The location of this event now becomes Masjid al-Qiblatayn ("the Mosque of the Two Qiblas").[5]

There are different reports about the qibla direction when Muhammad was in Mecca (before his migration to Medina). According to one report, cited by historian al-Tabari and exegete al-Baydawi, Muhammad prayed towards the Ka'bah. Another report, cited by al-Baladhuri and also by al-Tabari, says that Muhammad prayed towards Jerusalem while in Mecca. Another report, mentioned by Ibn Hisham's biography of Muhammad, says that Muhammad prayed in such a way as to simultaneously face the Ka'bah and Jerusalem.[5] Today Muslims of all branches, including the Sunni and the Shia, all toward the Ka'bah. Historically, one major exception was the Qarmatians, a now-defunct syncretic Shia sect which rejected the Ka'bah as the qibla; in 930, they sacked Mecca, took Ka'bah's Black Stone to their centre of power in Al-Ahsa, with the intention of starting a new era in Islam.[6][7][lower-alpha 1]

Religious aspects

.jpg)

| Part of a series on | ||||||

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

Family

|

||||||

|

Criminal

|

||||||

|

Etiquette

|

||||||

|

Economic

|

||||||

|

Hygiene

|

||||||

|

Military

|

||||||

| Islamic studies | ||||||

Etymologically, the Arabic word qibla (قبلة) means "direction". In Islamic ritual and law, it refers to a special direction faced by Muslims during prayers and other religious contexts.[5] Islamic religious scholars agree that facing the qibla is a necessary condition for the validity of salah—the Islamic ritual prayer—in normal conditions;[9] exceptions include prayers during the state of fear or of war, as well as non-obligatory prayers during travel.[10] In addition, the hadith also prescribed Muslims to face the qibla when entering the state of ihram for hajj, as after the middle jamrah (stone-throwing ritual) during the pilgrimage.[5] The Islamic etiquette (adab) calls for Muslim to turn the head of the animal when slaughtered, and the faces of the dead when buried, toward the qibla.[5] The qibla is the preferred direction when making a supplication and is to be avoided when defecating, urinating, and spitting.[5]

Inside a mosque, the qibla is usually indicated by a mihrab, a niche in its qibla-facing wall. In a congregational prayer, the imam (worship leader) stands in it or close to it, in front of the rest of the congregation.[11] The mihrab started became part of a mosque during the Umayyad period and its form is standardised during the Abbasid period; before that, the qibla of a mosque is known from the orientation of one of its walls, called the qibla wall. The term mihrab itself is only attested once in the Quran, but it refers to a place of prayer of the Israelites rather than a part of a mosque.[11][lower-alpha 2] The Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat, Egypt, one of the oldest mosques, is known to have been originally built without a mihrab, even though now one has been added.[12]

Ayn al-ka'bah and jihat al-ka'bah

Ayn al-ka'bah is facing the qibla so that an imaginary line extending from the person's line of sight would pass through the Ka'bah. This manner of observing the qibla is easily done inside the Great Mosque of Mecca and its surroundings, but given that the Ka'bah is less than 20 metres (66 ft) wide, this is virtually impossible from further locations.[13] For example, from Medina—with a 338 kilometres (210 mi) straight-line distance from the Ka'bah—a 1° deviation from the precise imaginary line—an error hardly noticeable when setting one's prayer mat or assuming one's posture—results in some 5.9 kilometres (3.7 mi) shift from the site of the Ka'bah.[14] This effect is amplified when further than Mecca:[15] from Jakarta, Indonesia—some 7,900 kilometres (4,900 mi) away, a 1° deviation causes more than 100 kilometres (62 mi) shift, and even an arc second's deviation—(1⁄3600 of a degree)— causes more than 100 metres (330 ft) of shift from the location of the Ka'bah.[16] In comparison, the construction process of a mosque can easily introduce up to 5° error from the calculated qibla, and the installation of prayer rugs inside the mosque as indicators for worshippers can add up to a further 5° deviation from the mosque's orientation.[16]

A minority of Islamic religious scholars—for example Ibn Arabi—considers ayn al-ka'bah to be obligatory during the ritual prayer, while others consider it only obligatory when one is able. For locations further than Mecca, scholars such as Abu Hanifa and Al-Qurtubi argue that it is permissible to assume jihat al-ka'bah, facing only the general direction of the Ka'bah.[17] Some further argues that the ritual condition of facing the qibla is already fulfilled simply when the imaginary line to the Ka'bah is within one's field of vision.[18] Therefore, for instance, there are legal opinions that accept the entire southeastern quadrant in Al-Andalus (historical Spain and Portugal), and the southwestern quadrant in Central Asia, to be valid qibla.[19] Arguments for the validity of jihat al-Ka'bah include the wording of the Quran which only commands Muslims to "turn [one's] face" toward the Great Mosque, and to avoid the impossible requirement which would result if ayn al-Ka'bah were to be obligatory in all places.[20] The Shafi'i school of Islamic law, as codified in Abu Ishaq al-Shirazi's Kitab al-Tanbih fi'l-Fiqh, argues that one must follow the qibla indicated by the local mosque when one is not near Mecca or, when not near a mosque, ask a trustworthy person. When this is not possible, one is to make one's own determination by means available in one's disposal.[21][22]

Determination

Theoretical basis: the great circle

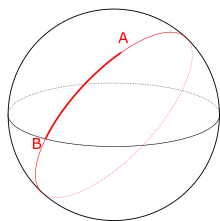

The great circle is the theoretical basis in most models that seek to scientifically determine the direction of qibla from a locality—in such models, the qibla is defined as direction of the great circle passing through the locality and the Ka'bah.[23][24] A great circle, also called the orthodrome, is any circle on a sphere whose centre is identical to the centre of the sphere. For example, all lines of longitude are great circles of the Earth, while the equator is the only line of latitude that is also a great circle (other lines of latitude are centered north or south of the centre of the Earth).[25] One of the properties of a great circle is that it indicates the shortest path connecting any pair of points along the circle—this is the basis of its use to determine the qibla. The great circle is similarly used to find the shortest flight path connecting two locations—therefore the qibla calculated using the great circle method is generally close to the direction of a direct flight from the locality to Mecca.[26] As the ellipsoid is a more accurate figure of the Earth than a perfect sphere, modern researchers have looked into using ellipsoidal models to calculate the qibla, replacing the great circle by the geodesics on an ellipsoid. This results in greatly more complicated calculations, while the improvement in accuracy falls well within the typical precision of the setting out of a mosque or the placement of a mat.[27] For example, calculations using the GRS 80 ellipsoidal model yields the qibla of 18°47′06″ for a location in San Francisco while the great circle method yields 18°51′05″.[28]

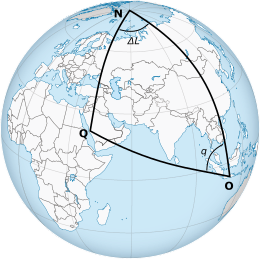

Calculations with spherical trigonometry

The great circle model is applied to calculate the qibla using spherical trigonometry—a branch of geometry that deals with the mathematical relations between the sides and angles of triangles formed by three great circles of a sphere (as opposed to the conventional trigonometry which deals with those of a two-dimensional triangle). In the following figure, a location , the Ka'bah , and the north pole form a triangle on the sphere of the earth. The qibla is indicated by , which is the direction of a great circle passing through both and . The qibla can also be expressed as an angle, (or ), of the qibla with respect to the north, also called the inhiraf al-qibla. This angle can be calculated as a mathematical function of the local latitude , the latitude of the Ka'bah , and the longitude difference between the locality and the Ka'bah .[29] This function is derived from the cotangent rule which applies in any spherical triangle with angles , , and sides , , :

Applying this formula in the spherical triangle (substituting )[31] and applying trigonometric identities obtain:

, or

[29]

For example, the qibla from the city of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, can be calculated as follows. The city's coordinates, , are 7.801389°S, 110.364444°E, while the Ka'bah's coordinates, , are 21.422478°N, 39.825183°E. The longitude difference between the two points are 110.364444° - 39.825183° = 70.539261°. Substituting the values into the formula obtains:

. which gives:

.

The calculated qibla is therefore 295°, or 25° north of west.[32]

This formula is derived by modern scholars, but equivalent methods have been known to Muslim astronomers since the 9th century (3rd century AH). They were developed by various Muslim scholars, including Habash al-Hasib (active in Damascus and Baghdad ca. 850 CE), Al-Nayrizi (Baghdad, ca. 900 CE), [33] Ibn Yunus (10th/11th century CE),[34] Ibn al-Haytham (11th century CE),[34] and Al-Biruni (11th century CE).[35] Today spherical trigonometry also underly nearly all application or websites which calculate the qibla.[23]

When the qibla angle with respect to the north, , is known, the true north needs to be known in order to find the qibla in practice. The methods to do this include observing the shadow of a vertical rod at the culmination of the sun—when the sun exactly crosses the local meridian. At this point, any vertical rod would cast a shadow oriented in the north–south direction. The result of this observation is very accurate but it requires an accurate determination of the local time of culmination as well as making the observation at that exact moment.[36] Another common method is using the compass, which is more practical because it can be done at any time; the disadvantage is that the north indicated by a magnetic compass differs from the true north.[16][37] This magnetic declination can measure up to 20°, varies in different places on Earth and changes over time.[16]

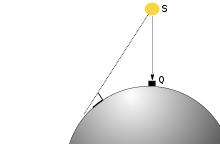

Shadow observation

As observed from Earth, the sun appears to "shift" between the Northern and Southern Tropics seasonally; additionally, it appears to move from east to west daily as a consequence of the earth's rotation. The combination of these two apparent motions means that every day the sun crosses the meridian once, usually not precisely overhead but to the north or to the south of the observer. In locations between the two tropics—latitudes lower than 23.5° north or south—at certain moments of the year the sun passes directly overhead. This happens when the sun crosses the meridian while being at the local latitude at the same time.[38]

The city of Mecca is among the places where this occurs, due to its location at 21°25′ N. It occurs twice on 28 May at about 12:18 Saudi Arabia Standard Time (SAST) or 9:18 UTC and 16 July at 12:27 SAST (9:27 UTC).[39][38] As the sun appears directly above Ka'bah, any vertical rod on earth that receives sunlight cast a shadow that indicates the qibla (see picture).[38] This method of finding the qibla is called rasd al-qiblat ("observing the qibla").[40][32] Since night falls on the hemisphere opposite of the Ka'ba, half the locations on Earth (including Australia as well as most of the Americas and the Pacific Ocean) cannot observe this directly.[41] Instead, such places observe the opposite phenomenon when the sun passes above the antipodal point of the Ka'bah (in other words, the sun passes directly underneath the Ka'bah), causing shadows in the opposite direction from those observed during rasd al-qiblat.[42][38] This occurs twice a year, on 14 January 00:30 SAST (21:30 UTC the previous day) and 29 November 00:09 SAST (21:09 UTC the previous day).[43] Observations made within five minutes of the rasd al-qiblat moments or its antipodal counterparts, or at the same time of day two days before or after each event, still show accurate directions with negligible difference.[38][39]

On the world map

Spherical trigonometry provides the shortest path from any point on earth to the Ka'bah, even though the indicated direction might seem counterintuitive when imagined on a flat world map. For example, the qibla from Alaska obtained through spherical trigonometry is almost due north.[23] This apparent counter-intuitiveness is caused by projections used by world maps, which by necessity distort the surface of the Earth. A straight line shown by the world map in using the Mercator projection is called the rhumb line or the loxodrome, which is used to indicate the qibla by a minority of Muslims.[44][lower-alpha 3] It can result in a dramatic differences in some places, for example in some of North America the flat map shows Mecca in the southeast while the great circle calculation shows northeast,[23] and in Japan the map shows southwest while the great circle shows northwest.[45] The majority of Muslims, however, follow the great circle method.[23]

Traditional methods

Historical records and surviving old mosques show that throughout history the qibla was often determined by simple methods based on tradition or "folk science" not based on mathematical astronomy. Some early Muslims uses due south everywhere as qibla, following Muhammad's instruction to face south while he was in Medina (Mecca is due south of Medina) in a literal manner. Some mosques in as far as al-Andalus to the west and Central Asia to the east faces south even though Mecca is nowhere near that direction.[46] In various places, there is also the "qiblas of the companion" (qiblat al-sahaba), those which were used in those places by the Companions of the Prophet—the first generation of Muslims, who are considered role models in Islam. Such directions were used by some Muslims in the following centuries, side by side with other directions, even after Muslim astronomers used calculations to find more accurate directions to Mecca. Directions described as the qiblas of the companions include due south in Syria and Palestine,[47] the direction of the winter sunrise in Egypt, and the direction of the winter sunset in Iraq.[48] The direction of the winter sunrise and sunset are also traditionally favoured because they are parallel to the walls of the Ka'bah.[49]

Development of methods

Pre-astronomy

The determination of qibla is an important problems for Muslim communities throughout history. Muslims are required to know the qibla in order to perform their daily prayers, and it is also needed to determine the orientation of mosques.[50] When Muhammad lived among the Muslims in Medina (which, like Mecca, is also in the Hejaz region), he prayed due south, according to the known direction of Mecca. Within the few generations after Muhammad's death in 632, Muslims have reached places far away from Mecca, presenting the problem of determining the qibla in new places.[51] Mathematical methods based on astronomy would only develop at the end of the eighth century or the beginning of the ninth and even then they were not initially popular. Therefore, early Muslims relied on non-astronomical methods.[52]

There is a wide range of traditional methods in determining the qibla in the early Islamic period, resulting in different directions even from the same place. In addition to due south (used because it was the direction to which Muhammad prayed from Medina) and directions known as the qiblas of the companions (varies by place), the Arabs also knew a form of "folk" astronomy—called so by David A. King to distinguish it from conventional astronomy which is an exact science—originating from pre-Islamic traditions.[48] It used natural phenomenon, including the observation of the Sun, the Moon, the stars, and wind, without any basis in mathematics. These methods yields specific directions in individual localities, often using the fixed setting and rising points of a specific star, the sunrise or sunset at the equinoxes or at the summer or the winter solstices.[53] Such qibla directions recorded in historical sources include: sunrise at the equinoxes (due west) in the Maghreb, sunset at the equinoxes (due east) in India, the origin of the north wind or the fixed location of the North Star in Yemen, the rising point of the star Suhayl (Canopus) in Syria, and the midwinter sunset in Iraq.[53] Such directions appear in texts of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) and texts of folk astronomy. Astronomers (aside from folk astronomers) typically do not comment on these methods, but they were not opposed by Islamic legal scholars.[54] The traditional directions were still in use when mathematical methods later developed and found different directions to Mecca, and they still appear in some surviving medieval mosques today.[47]

With astronomy

The study of astronomy—known as ilm al-falaq in the Islamic intellectual tradition—began to appear in the Islamic World in the second half of the eighth century, centered in Baghdad, the principal city of the Abbasid Caliphate. Initially, the science was introduced through the works if Indian authors, but since the ninth century the works of Greek astronomers such as Ptolemy were translated to Arabic and became the main reference in the field.[55] Muslim astronomers preferred Greek astronomy because they consider it to be better supported by theoretical explanations and therefore can be developed as an exact science; however, the influence of Indian astronomy survives especially on the compilation of astronomical tables.[56] This new science is applied to develop new methods of determining the qibla, making use of the concept of latitudes and longitudes introduced in Ptolemy's Geography as well as trigonometric formulae developed by Muslim scholars.[57] Most textbooks of astronomy written in the medieval Islamic World contain a chapter on the determination of qibla, considered one of the many things connecting astronomy with the Islamic law (sharia).[29][58] According to David A. King, various medieval solutions for the determination of qibla "bear witness to the development of mathematical methods from the 3rd/9th to the 8th/14th centuries and to the level of sophistication in trigonometry and computational techniques attained by these scholars."[29]

The first mathematical methods developed in the early ninth century were approximate solutions to the mathematical problem, usually using a flat map or two-dimensional geometry. Because in reality the earth is spherical, the directions found were not exact, but they were sufficient for locations relatively close to Mecca (including as far as Egypt and Iran) because the errors were only less than 2°.[59]

Exact solutions based on three-dimensional geometry and spherical trigometry began to appear in middle of 9th century. Habash al-Hasib (fl. c. 850 M in Baghdad and Damascus) wrote an early example of such solutions, using an "analemma", or a two-dimensional procedure to derive formulas in spherical trigonometry. His procedure involves working with a circle and a series of points and lines drawn in a specific manner to find a direction now known to be equivalent to the solution obtained from the modern formula.[60][lower-alpha 4] Another group of solution uses trigonometric formulas, for example Al-Nayrizi from Baghdad (fl. c. 900) developed a mathematical procedure using a four-step application of Menelaus's theorem.[61][lower-alpha 5] Subsequent scholars, including Ibn Yunus, Abu al-Wafa, Ibn al-Haitham and Al-Biruni, proposers other methods which are confirmed to be accurate from the viewpoint of modern astronomy, using either analemmas or direct application of formulas.[62]

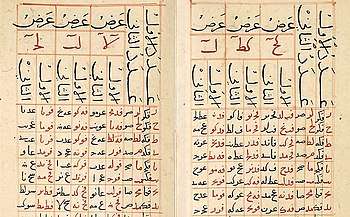

Muslim astronomers subsequently used these methods to compile tables showing qibla from a list of locations, grouped by their latitude and longitude differences from Mecca. The oldest known example was written in Baghdad ca. 9th century CE containing entries for each degrees and arc minutes up to 20°.[63] In the fourteenth century, Shams al-Din al-Khalili, an astronomer who serves as a muwaqqit (timekeeper) in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, compiled a table of qibla for 2,880 coordinates with longitude difference of up to 60° from Mecca, and with latitudes ranging from 10° to 50°.[62][63] King opined that among the medieval qibla tables, al-Khalili's work is "the most impressive from the view of its scope and its accuracy".[63]

The accuracy of applying these methods to actual locations depend on the accuracy of its input parameters—the local latitude and the latitude of Mecca, and the longitude difference. At the time of the development of these methods, the latitude of a location can be determined to several arc minutes' accuracy, but there was no accurate method to determine a location's longitude.[64] Common approximate methods used to determine the longitude difference include comparing the local timing of lunar eclipse versus the timing in Mecca, or measuring the distance of caravan routes;[62][35] the Central Asian scholar Al-Biruni made his estimate by averaging various approximate methods.[62] Because the longitude inaccuracy, medieval qibla calculations (including those using mathematically accurate methods) differ from the modern values. For example, while the Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo was built using the "qibla of the astronomers", but the mosque's qibla (127°) somewhat differs from the result of modern calculations (135°) because the longitude difference used was off by 3°.[65]

Accurate longitude values in the Islamic world were only available after the application of cartographic surveys in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Modern coordinates, along with new technologies such as GPS satellites and electronic instruments, resulted in the development of practical instruments to calculate the qibla.[66] Qibla found using modern instruments might differ from the direction of mosques, because a mosque might be built before the advent of modern data, and orientation inaccuracies might have been introduced during the building process of modern mosques.[66][21] When this is known, sometimes the direction of the mosque's mihrab is still observers, and sometimes a marker is added (such as lines drawn in the mosque) that can be followed instead of the mihrab.[21]

Instruments

Muslims use various instrument to find the qibla when not near a mosque. The qibla compass is a magnetic compass which include a table or a list of qibla angle from major settlements. An electronic version could use satellite coordinates in order to calculate and indicate the qibla automatically.[66] Qibla compasses have existed since around 1300, supplemented by the list of qibla angles often written on the instruments themselves.[67] Hotel rooms with Muslim guests may use a sticker showing the qibla on the ceiling or a drawer.[16] With the advent of computing, various mobile apps and websites use formulae to calculate the qibla for their users.[23][68]

Diversity

Early Islamic world

Because varying methods have been used to determine the qibla, mosques are built throughout history in different directions, including some mosques that still stand today.[69] Methods based on astronomy and mathematics were not always used,[70] and the same determination method can yield different qibla due to difference in the accuracy of data and calculation.[71] Egyptian historian Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442) recorded various qibla used in Cairo of his time: 90° (due east), 117° (winter sunrise, "qibla of the sahaba"), 127° (calculated by astronomers, such as Ibn Yunus), 141° (Mosque of Ibn Tulun), 156° (the rising point of Suhayl/Canopus), 180° (due south, emulating the qibla of Muhammad in Medina), and 204° (the setting point of Canopus). The modern qibla for Cairo is 135°, which was not known at the time.[72] This diversity also result in the non-uniform layout in Cairo's districts, because the streets are often oriented according to the orientation of the mosques. Muslim historical records also indicate the diversity of qibla in other major cities, including Cordoba (113°, 120°, 135°, 150°, and 180° were recorded in the 12th century) and Samarkand (180°, 225°, 230°, 240°, and 270° were recorded in the 11th century).[72] According to the doctrine of jihat al-ka'bah, the diverse directions of qibla are still valid as long as they are still in the same broad direction.[19]

North America

Places long settled by Muslim populations tend to have resolved the question of the direction of qibla over time. Other places, like the United States and Canada, have only had large Muslim communities in the past several decades, and the determination of qibla can be a matter of debate.[74] The Islamic Center of Washington, D.C. was built in 1953 facing slightly north of east and initially puzzled some observers, including Muslims, because Washington, D.C.'s latitude is 17°30′ more northerly than that of Mecca. Even though line drawn on world maps—such as those using the Mercator projection—would suggest a southeastern direction to Mecca, astronomical calculations using the great circle method do yield a north-of-east direction (56°33′).[73] Nevertheless, most early mosques in the United States face east or southeast, following the apparent direction in world maps.[74] As the Muslim community grew and the number of mosque increased, in 1978 an American Muslim scientist S. Kamal Abdali, wrote an article arguing that the correct qibla from North America was north or northeast as calculated by the great circle method, which identifies the shortest path to Mecca.[75][76][23] Abdali's conclusion was widely circulated and then accepted by the Muslim community, and mosques were subsequently reoriented as a result.[74] In 1990, two religious scholars Riad Nachef and Samir Kadi published a book arguing for a southeastern qibla, writing that the north/northeast qibla was invalid and resulted from a lack of religious knowledge.[77][26] The two opinions resulted in a period of debate about the correct qibla,[77] and eventually most North American Muslims accepted the north/northeast qibla with a minority following the east/southeast qibla.[23][78]

Indonesia

Variation of the qibla also occurs in Indonesia, the country with the world's largest world Muslim population. The astronomically calculated qibla ranges from 291°—295° (21°—25° north of west) depending on the exact location in the archipelago.[79] However, the qibla is often traditionally known as simply 'the west', resulting in mosques built oriented due west or to the direction of sunset—which slightly varies throughout the year. Different opinions exist among Indonesian Islamic astronomers: Tono Saksono et al. argues that facing the qibla during prayers is more of a "spiritual prerequisite" than a precise physical one, and that an exact direction to the Ka'bah itself from thousands of kilometres away requires an extreme precision impossible to achieve when building a mosque or when standing for prayers.[16] On the other hands, Muhammad Hadi Bashori opined that "correcting the qibla is indeed a very urgent thing," and can be guided by simple methods such as observing the shadow.[80] In the history of the region, disputes about the qibla has also occurred in the then-Dutch East Indies in the 1890s. When the Indonesian scholar and future founder of Muhammadiyah, Ahmad Dahlan returned from his Islamic and astronomy studies in Mecca he found that mosques in the royal capital of Yogyakarta had inaccurate qiblas, including the Kauman Great Mosque which faced due west. His efforts in adjusting the qibla was opposed by the traditional ulama of the Yogyakarta Sultanate, and a new mosque built by Dahlan using his calculations was demolished by a mob. Dahlan rebuilt his mosque in the 1900s and later the Kauman Great Mosque too would be reoriented using the astronomically calculated qibla.[81][82]

Outer space

The issue of qibla from outer space publicly arose before the spaceflight of Sheikh Muszaphar Shukor, a Malaysian surgeon who is a devout Muslim, to the International Space Station (ISS) on October 2007.[83] The ISS orbits the earth in high speed so that the direction to Mecca changes significantly in matters of seconds.[23] Before his departure, Sheikh Muzsaphar requested guidance from Malaysian religious authorities about the performance of Islamic practices in space, including how to pray, fast, and determine the qibla. In its response, the Malaysian National Fatwa Council recommended four options in regard to the qibla, in order of priority: 1) the Ka'bah itself 2) the projection of the Ka'bah into space 3) the Earth 4) "wherever".[23] The authors of the fatwa intended that it will also be used as guidelines for future Muslim astronauts, and it has been translated into multiple languages.[83] In line with the Malaysian fatwa council, other Muslim scholars argue for the importance of flexibility and adapting the qibla requirement to what an astronaut is capable of fulfilling. Khaleel Muhammad of the San Diego State University opined "God does not take a person to task for that which is beyond his/her ability to work with" and Abdali argued that concentration during a prayer is more important than the exact orientation, and suggest keeping the qibla direction at the start of a prayer instead of "worrying about possible changes in position".[23] Before Sheikh Muszaphar's mission, at least eight Muslims had flown to space, but none of them publicly discussed issues relating to worship in space.[84]

See also

- Black Stone

- Craig retroazimuthal projection

- Holy site

- Mizrâḥ, the Jewish equivalent of the Qiblah

- Qiblih, the Bahá'í equivalent

- Praying towards Mecca in space

Notes

- This act was condemned both by the Sunni Abbasid caliph and the Shia Fatimid one. The Qarmatian leader Abu Tahir al-Jannabi refused the request of the two caliphs to return the Black Stone, and it was only returned in 951 after the death of Abu Tahir and payments from the Abbasid caliphate.[8]

- This reference occurs in Quran 19:11

- For an example of the loxodrome used to find qibla, see #North America.

- The details of this method and its proof are provided in King 1996, pp. 144–145

- The details of this method and its proof are provided in King 1996, pp. 145–146

References

Citations

- Wensinck 1978, p. 317.

- Wensinck 1978, p. 318.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, pp. 97–98.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 104.

- Wensinck 1986, p. 82.

- Wensinck 1978, p. 321.

- Daftary 2007, p. 149.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 149–151.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 103.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 91.

- Kuban 1974, p. 3.

- Kuban 1974, p. 4.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, pp. 104–105.

- Saksono, Fulazzaky & Sari 2018, p. 137.

- Saksono, Fulazzaky & Sari 2018, p. 134.

- Saksono, Fulazzaky & Sari 2018, p. 136.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, pp. 92, 95.

- King 1996, p. 134.

- King 1996, pp. 134–135.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 95.

- Wensinck 1986, p. 83.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 94.

- Di Justo 2007.

- King 2004, p. 166.

- Abo-Zahhad, Ahmed & Mourad 2013, p. 172.

- Almakky & Snyder 1996, p. 31.

- Saksono, Fulazzaky & Sari 2018, pp. 132–134.

- Almakky & Snyder 1996, p. 35.

- King 1986, p. 83.

- An equivalent formula in Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 119

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 119.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 123.

- King 1986, pp. 85–86.

- King 1986, p. 85.

- King 1986, p. 86.

- Ilyas 1984, pp. 171–172.

- Ilyas 1984, p. 172.

- Raharto & Surya 2011, p. 25.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 125.

- Raharto & Surya 2011, p. 24.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, pp. 125–126.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, pp. 126–127.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 127.

- Almakky & Snyder 1996, pp. 31–32.

- Hadi Bashori 2015, p. 110.

- King 1996, p. 130.

- King 1996, pp. 130–131.

- King 1996, p. 132.

- King 1996, p. 132, also figure 4.2 in p. 131.

- King 1996, p. 128.

- King 1996, pp. 130–132.

- King 1996, pp. 128–129.

- King 1996, p. 133.

- King 1996, p. 132–133.

- Morelon 1996b, p. 20–21.

- Morelon 1996b, p. 21.

- King 1996, p. 141.

- Morelon 1996a, p. 15.

- King 1996, pp. 142-143.

- King 1996, pp. 144–145.

- King 1996, pp. 145–146.

- King 1996, p. 147.

- King 2004, p. 170.

- King 1996, p. 153.

- King 1996, pp. 153–154.

- King 2004, p. 177.

- King 2004, p. 171.

- MacGregor 2018, p. 130.

- Almakky & Snyder 1996, p. 29.

- King 2004, p. 175.

- Almakky & Snyder 1996, p. 32.

- King 2004, pp. 175–176.

- May 1953, p. 367.

- Bilici 2012, p. 54.

- Abdali, S. Kamal (1978). Prayers schedule for North America. Indianapolis: American Trust Publications. OCLC 27738892.

- Bilici 2012, pp. 54–55.

- Bilici 2012, pp. 55–56.

- Bilici 2012, p. 57.

- Hadi Bashori 2014, pp. 59–60.

- Hadi Bashori 2014, pp. 60–61.

- Kersten 2017, p. 130.

- Nashir 2015, p. 77.

- Lewis 2013, p. 114.

- Lewis 2013, p. 109.

Bibliography

- Abo-Zahhad, Mohammed; Ahmed, Sabah M.; Mourad, Mohamed (2013). "Services and Applications Based on Mobile User's Location Detection and Prediction". International Journal of Communications, Network and System Sciences. Scientific Research Publishing. 6 (4): 167–175. doi:10.4236/ijcns.2013.64020. ISSN 1913-3723.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Almakky, Ghazy; Snyder, John (1996). "Calculating an Azimuth from One Location to Another A Case Study in Determining the Qibla to Makkah". Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization. University of Toronto Press. 33 (2): 29–36. doi:10.3138/C567-3003-1225-M204. ISSN 0317-7173.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bilici, Mucahit (2012). Finding Mecca in America: How Islam Is Becoming an American Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92287-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46578-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Di Justo, Patrick (2007). "A Muslim Astronaut's Dilemma: How to Face Mecca From Space". WIRED. Condé Nast.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadi Bashori, Muhammad (2014). Penanggalan Islam (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo. ISBN 978-602-02-3675-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadi Bashori, Muhammad (2015). Pengantar Ilmu Falak (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Pustaka Al Kautsar. ISBN 978-979-592-701-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ilyas, Mohammad (1984). A modern guide to astronomical calculations of Islamic calendar, times & qibla. Kuala Lumpur: Berita Publishing. ISBN 9789679690095. OCLC 13512629.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kersten, Carool (2017). History of Islam in Indonesia: Unity in Diversity. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8187-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, David A. (1986). "Ḳibla: Astronomical Aspects". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 83–88. ISBN 90-04-07819-3.

- King, David A. (1996). "Astronomy and Islamic Society". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. I. Routledge. pp. 128–184.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, David A. (2004). "The Sacred Geography of Islam". In Koetsier, Teun; Bergmans, Luc (eds.). Mathematics and the Divine: A Historical Study. Elsevier. pp. 161–178. ISBN 978-0-08-045735-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kuban, Doğan (1974). The Mosque and Its Early Development. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-03813-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Cathleen S. (2013). "Muslims in Space: Observing Religious Rites in a New Environment" (PDF). Astropolitics. 11 (1–2): 108–115. Bibcode:2013AstPo..11..108L. doi:10.1080/14777622.2013.802622. ISSN 1477-7622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacGregor, Neil (2018). Living with the Gods: On Beliefs and Peoples. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-30830-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- May, Don (1953). "You Can't Build That Mosque With a Compass". Surveying and Mapping. Washington, D.C.: American Congress on Surveying and Mapping. 13 (1): 367–368.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morelon, Régis (1996a). "General survey of Arabic astronomy". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. I. Routledge. pp. 1–19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morelon, Régis (1996b). "Eastern Arabic astronomy between the eight and the eleventh centuries". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. I. Routledge. pp. 20–57.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nashir, Haedar (2015). Muhammadiyah: a Reform Movement. Surakarta: Muhammadiyah University Press. ISBN 978-602-361-012-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raharto, Moedji; Surya, Dede Jaenal Arifin (2011). "Telaah Penentuan Arah Kiblat dengan Perhitungan Trigonometri Bola dan Bayang-Bayang Gnomon oleh Matahari". Jurnal Fisika Himpunan Fisika Indonesia (in Indonesian). University of Indonesia. 11 (1): 23–29. ISSN 0854-3046.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saksono, Tono; Fulazzaky, Mohamad Ali; Sari, Zamah (2018). "Geodetic analysis of disputed accurate qibla direction". Journal of Applied Geodesy. De Gruyter. 12 (2): 129–138. Bibcode:2018JAGeo..12..129S. doi:10.1515/jag-2017-0036. ISSN 1862-9024.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wensinck, Arent Jan (1978). "Kaʿba". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 317–322. OCLC 758278456.

- Wensinck, Arent Jan (1986). "Ḳibla: Ritual and Legal Aspects". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 82–83. ISBN 90-04-07819-3.

Further reading

- King, David A. (1999). World maps for finding the direction and distance to Mecca : innovation and tradition in Islamic science. Islamic philosophy, theology, and science. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-11367-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qibla. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Kiblah. |

- Full information of the Kaaba

- The City of Jerusalem in Islam (Al-Quds) About.com

- Second Year of the Hijra at al-islam.org (Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project)

- Qiblah In North America – argues that the Qiblah is based on a rhumb line path

- Determining the Sacred Direction of Islam

- Denis Roegel: An Extension of Al-Khalīlī's Qibla Table to the Entire World, 2008

Online tools

- Qiblah.us

- Accurate Qibla calculator Gives highly accurate Qibla and distance to Mecca using the WGS84 ellipsoid

- Qibla Direction

- eQibla.com – worldwide Qibla Direction (including documents and Qibla formula)

- Qiblah Direction Finder

- QiblaDirection.com uses Google Maps and Google Earth to draw a line between your location and Mecca, automatically gives the prayer times for your location

- Find Qibla using rhumb line and great circle, also compute magnetic declination

- Qibla finder Widget for Konfabulator

- Type your address to see a map showing your Qibla Direction

- Qibla Finder

.jpg)