Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley, also spelled Phyllis and Wheatly (c. 1753 – December 5, 1784) was the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry.[1][2] Born in West Africa, she was sold into slavery at the age of seven or eight and transported to North America. She was purchased by the Wheatley family of Boston, who taught her to read and write and encouraged her poetry when they saw her talent.

Phillis Wheatley | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Phillis Wheatley, attributed by some scholars to Scipio Moorhead | |

| Born | 1753 West Africa (likely Gambia or Senegal) |

| Died | December 5, 1784 (aged 31) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | English |

| Period | American Revolution |

| Notable works | Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) |

| Spouse | John Peters |

| Children | Three |

On a 1773 trip to London with her master's son, seeking publication of her work, she was aided in meeting prominent people who became patrons. The publication in London of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral on September 1, 1773, brought her fame both in England and the American colonies. Figures such as George Washington praised her work.[3] A few years later, African-American poet Jupiter Hammon praised her work in a poem of his own.

Wheatley was emancipated (set free) by the Wheatleys shortly after the publication of her book.[4] She married in about 1778. Two of her children died as infants. After her husband was imprisoned for debt in 1784, Wheatley fell into working poverty and died of illness. Her last infant son died soon after.

Early life

Although the date and place of her birth are not documented, scholars believe that Phillis Wheatley was born in 1753 in West Africa, most likely in present-day Gambia or Senegal.[6] Wheatley was sold by a local chief to a visiting trader, who took her to Boston in the British colony of Massachusetts, on July 11, 1761,[7] on a slave ship called The Phillis.[8] It was owned by Timothy Fitch and captained by Peter Gwinn.[8]

On arrival she was re-sold to John Wheatley, a wealthy Boston merchant and tailor who bought the young girl as a servant for his wife Susanna. John and Susanna Wheatley named the young girl Phillis, after the slave ship that had transported her to America. She was given their last name of Wheatley, as was a common custom if any surname was used for enslaved people.

The Wheatleys' 18-year-old daughter, Mary, first tutored Phillis in reading and writing. Their son Nathaniel also helped her. John Wheatley was known as a progressive throughout New England; his family gave Phillis an unprecedented education for an enslaved person, and for a female of any race. By the age of 12, she was reading Greek and Latin classics and difficult passages from the Bible. At the age of 14, she wrote her first poem, "To the University of Cambridge, in New England."[9][10] Recognizing her literary ability, the Wheatley family supported Phillis's education and left the household labor to their other domestic slaves. The Wheatleys often showed off her abilities to friends and family. Strongly influenced by her studies of the works of Alexander Pope, John Milton, Homer, Horace and Virgil, Phillis began to write poetry.[11]

Later life

In 1773, at the age of 20, Phillis accompanied Nathaniel Wheatley to London in part for her health, but also because Susanna believed Phillis would have a better chance of publishing her book of poems there.[12] She had an audience with the Lord Mayor of London and other significant members of British society. (An audience with King George III was arranged, but Phillis returned to Boston before it could take place.) Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, became interested in the talented young African woman and served as the patron of Wheatley's volume of poems, securing its publication in London in the summer of 1773. As Hastings was ill, she and Wheatley never met.[13]

After her book was published, by November 1773 the Wheatley family emancipated (formally freed) Phillis Wheatley. Her former mistress Susanna Wheatley died in the spring of 1774, and John Wheatley in 1778. Shortly after, Phillis Wheatley met and married John Peters, a free black grocer. They struggled with poor living conditions and the deaths of two babies.[14]

Other writings

Phillis Wheatley wrote a letter to Reverend Samson Occom, commending him on his ideas and beliefs of how the slaves should be given their natural born rights in America. Wheatley also exchanged letters with the British philanthropist John Thornton, who discussed Wheatley and her poetry in correspondence with John Newton.[15] Along with her poetry, she was able to express her thoughts, comments and concerns to others.[16]

In 1775, she sent a copy of a poem entitled, "To His Excellency, George Washington," to the military general. In 1776, Washington invited Wheatley to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which she did in March 1776.[17] Thomas Paine republished the poem in the Pennsylvania Gazette in April 1776.[18]

In 1773, sometime between July and October, Wheatley was emancipated by the Wheatley family shortly after her book, Poems on Subjects Religious and Moral, was published in London.

In 1779, Wheatley submitted a proposal for a second volume of poems, but was unable to publish it because of her financial circumstances, the loss of patrons after her emancipation (publication of books was often based on gaining subscriptions for guaranteed sales beforehand), and the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). However, some of her poems that were to be published in the second volume were later published in pamphlets and newspapers.[19]

Her husband John Peters was improvident, and imprisoned for debt in 1784. The impoverished Wheatley had a sickly infant son. She went to work as a scullery maid at a boarding house to support them, a kind of domestic labor that she had never formerly performed. Wheatley became ill and died on December 5, 1784, at the age of 31.[20] Her infant son died soon after.

Poetry

| |

In 1768, Wheatley wrote "To the King's Most Excellent Majesty", in which she praised King George III for repealing the Stamp Act.[4] As the American Revolution gained strength, Wheatley's writing turned to themes that expressed ideas of the rebellious colonists.

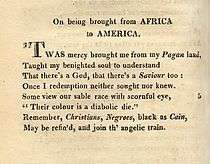

In 1770 Wheatley wrote a poetic tribute to the evangelist George Whitefield, which received widespread acclaim. Her poetry expressed Christian themes, and many poems were dedicated to famous figures. Over one-third consist of elegies, the remainder being on religious, classical, and abstract themes.[22] She seldom referred to her own life in her poems. One example of a poem on slavery is "On being brought from Africa to America":[23]

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

"Their colour is a diabolic dye."

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

Historians have commented on her reluctance to write about slavery. Perhaps it was because she had conflicting feelings about the institution. Also, she wrote her early work while still enslaved, even if she was well treated. In the poem above, critics have said that she praises slavery because it brought her to Christianity. But, in another poem, she wrote that slavery was a cruel fate.[24]

Many colonists found it difficult to believe that an African slave was writing "excellent" poetry. Wheatley had to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772.[25][26] She was examined by a group of Boston luminaries, including John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey, John Hancock, Thomas Hutchinson, the governor of Massachusetts; and his lieutenant governor Andrew Oliver. They concluded she had written the poems ascribed to her and signed an attestation, which was included in the preface of her book of collected works: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, published in London in 1773. Publishers in Boston had declined to publish it, but her work was of great interest to influential people in London.

There, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon and the Earl of Dartmouth acted as patrons to help Wheatley gain publication. Her poetry received comment in The London Magazine in 1773, which published as a "specimen" of her work her poem 'Hymn to the Morning', and said: "these poems display no astonishing works of genius, but when we consider them as the productions of a young, untutored African, who wrote them after six months careful study of the English language, we cannot but suppress our admiration for talents so vigorous and lively."[27] Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was printed in 11 editions until 1816.[28]

In 1778, the African-American poet Jupiter Hammon wrote an ode to Wheatley ("An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley"). His master Lloyd had temporarily moved with his slaves to Hartford, Connecticut, during the Revolutionary War. Hammon thought that Wheatley had succumbed to what he believed were pagan influences in her writing, and so his "Address" consisted of 21 rhyming quatrains, each accompanied by a related Bible verse, that he thought would compel Wheatley to return to a Christian path in life.[29]

In 1838 Boston-based publisher and abolitionist Isaac Knapp published a collection of Wheatley's poetry, along with that of enslaved North Carolina poet George Moses Horton, under the title Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, A Native African and a Slave. Also, Poems by a Slave.[30] Wheatley's memoir was earlier published in 1834 by Geo W. Light, but did not include poems by Horton.

Style, structure, and influences on poetry

Wheatley believed that the power of poetry is immeasurable.[31] John C. Shields, noting that her poetry did not simply reflect the literature she read but was based on her personal ideas and beliefs, writes,:

"Wheatley had more in mind than simple conformity. It will be shown later that her allusions to the sun god and to the goddess of the morn, always appearing as they do here in close association with her quest for poetic inspiration, are of central importance to her."

This poem is arranged into three stanzas of four lines in iambic tetrameter, followed by a concluding couplet in iambic pentameter. The rhyme scheme is ABABCC.[31][32]

She repeated three primary elements: Christianity, classicism, and hierophantic solar worship.[33] The hierophantic solar worship was part of what she brought with her from Africa; the worship of sun gods is expressed as part of her African culture, which may be why she used so many different words for the sun. For instance, she uses Aurora eight times, "Apollo seven, Phoebus twelve, and Sol twice."[33] Shields believes that the word "light" is significant to her as it marks her African history, a past that she has left physically behind.[33]

He notes that Sun is a homonym for Son, and that Wheatley intended a double reference to Christ.[33] Wheatley also refers to "heav'nly muse" in two of her poems: "To a Clergy Man on the Death of his Lady" and "Isaiah LXIII," signifying her idea of the Christian deity.[34]

Shields believes that her use of classicism set her work apart from that of her contemporaries: "Wheatley's use of classicism distinguishes her work as original and unique and deserves extended treatment."[35] Shields sums up her writing as being "contemplative and reflective rather than brilliant and shimmering."[32]

Legacy and honors

With the 1773 publication of Wheatley's book Poems on Various Subjects, she "became the most famous African on the face of the earth."[36] Voltaire stated in a letter to a friend that Wheatley had proved that black people could write poetry. John Paul Jones asked a fellow officer to deliver some of his personal writings to "Phillis the African favorite of the Nine (muses) and Apollo."[36] She was honored by many of America's founding fathers, including George Washington, who wrote to her (after she wrote a poem in his honor) that "the style and manner [of your poetry] exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents."[37]

Critics consider her work fundamental to the genre of African-American literature,[1] and she is honored as the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry and the first to make a living from her writing.[38]

- In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Phillis Wheatley as one of his 100 Greatest African Americans.[39]

- Wheatley is featured, along with Abigail Adams and Lucy Stone, in the Boston Women's Memorial, a 2003 sculpture on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts.

- In 2012, Robert Morris University named the new building for their School of Communications and Information Sciences after Phillis Wheatley.[40]

- Wheatley Hall at UMass Boston is named for Phyllis Wheatley.[41]

She is commemorated on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.[42] The Phyllis Wheatley YWCA in Washington, D.C. and the Phyllis Wheatly High School in Houston, Texas, are named for her, as was the historic Phyllis Wheatley School in Jensen Beach, Florida, now the oldest building on the campus of American Legion Post 126, (Jensen Beach, Florida). A branch of the Richland County Library in Columbia, SC, which offered the first library services to black citizens, is named for her. Phillis Wheatley Elementary School, New Orleans opened in 1954 in Treme, one of the oldest African-American neighborhoods in the US.

On July 16, 2019, at the London site where A. Bell Booksellers published Wheatley's first book in September 1773 (8 Aldgate, now the site of the Dorsett City Hotel), the unveiling took place of a blue plaque honoring her, organized by the Nubian Jak Community Trust and Black History Walks was unveiled in London.[43][44]

Wheatley is the subject of a project and play by Ade Solanke entitled Phillis in London.[45]

See also

- African American literature

- AALBC.com

- Elijah McCoy

- Jupiter Hammon

- Phillis Wheatley Club

- Slave narrative

- List of slaves

References

- Gates, Henry Louis, Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America's Second Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers, Basic Civitas Books, 2010, p. 5.

- For example, in the name of the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA in Washington, D.C., where "Phyllis" is etched into the name over its front door (as can be seen in photos and corresponding text for that building's National Register nomination).

- Meehan, Adam; J. L. Bell. "Phillis Wheatley · George Washington's Mount Vernon". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Smith, Hilda L. (2000), Women's Political and Social Thought: An Anthology, Indiana University Press, p. 123.

- Adelaide M. Cromwell (1994), The Other Brahmins: Boston's Black Upper Class, 1750–1950, University of Arkansas Press, OL 1430545M

- Carretta, Vincent. Complete Writings by Phillis Wheatley, New York: Penguin Books, 2001.

- Odell, Margaretta M. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave, Boston: Geo. W. Light, 1834.

- Doak, Robin S. Phillis Wheatley: Slave and Poet, Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2007.

- Brown, Sterling (1937). Negro Poetry and Drama. Washington, DC: Westphalia Press. ISBN 1935907549.

- Wheatley, Phillis (1887). Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Denver, Colorado: W.H. Lawrence. pp. 120.

- White, Deborah (2015). Freedom on My Mind. Boston/New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-312-64883-1.

- Charles Scruggs (1998). "Phillis Wheatley". In G. J. Barker-Benfield (ed.). Portraits of American Women: From Settlement to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 106.

- Catherine Adams; Elizabeth H. Pleck (2010). Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195389081.

- Darlene Clark Hine; Kathleen Thompson (2009). A Shining Thread of Hope. New York: Random House. p. 26.

- Bilbro, Jeffrey (Fall 2012). "Who are lost and how they're found: redemption and theodicy in Wheatley, Newton, and Cowper". Early American Literature. 47 (3): 570–75. doi:10.1353/eal.2012.0054.

- White (2015). Freedom On My Mind. pp. 146–147.

- Grizzard, Frank E. (2002). George Washington: A Biographical Companion. Greenwood, CT: ABC-CLIO. p. 349.

- Vincent Carretta, ed. (2013). Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth Century. Louisville: University of Kentucky Press. p. 70.

- Yolanda Williams Page, ed. (2007). "Phillis Wheatley". Encyclopedia of African American Women Writers, Volume 1. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 610.

- Page, ed. (2007). "Phillis Wheatley". Encyclopedia of African American Women Writers, Volume 1. p. 611.

- "Analysis of Poem "On Being Brought From Africa to America" by Phillis Wheatley". LetterPile. 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- Phillis Wheatley page, comments on Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, University of Delaware. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- "On Being Brought from Africa to America"., Web Texts, Virginia Commonwealth University

- Wheatley, Phillis (1773). ""To the Right Honourable WILLIAM, Earl of DARTMOUTH, His Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for North-America, &c."". Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral. London. p. 74.

- Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah (eds), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Basic Civitas Books, 1999, p. 1171.

- Ellis Cashmore, review of The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature, Nellie Y. McKay and Henry Louis Gates, eds, New Statesman, April 25, 1997.

- "The London magazine, or, Gentleman's monthly intelligencer 1773". HathiTrust. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- Busby, Margaret, "Phillis Wheatley", in Daughters of Africa, 1992, p. 18.

- Faherty, Duncan F. "Hammon, Jupiter". American National Biography Online. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- Cavitch, Max. American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007: 193. ISBN 978-0-8166-4892-4.

- Shields, John C. "Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism", American Literature 52.1 (1980): 97–111. Retrieved November 2, 2009, p. 101.

- Shields, "Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism", American Literature 52.1 (1980), p. 100.

- Shields, "Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism", American Literature 52.1 (1980), p. 103.

- Shields, "Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism", American Literature 52.1 (1980), p. 102.

- Shields, "Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism", American Literature 52.1 (1980), p. 98.

- Gates, The Trials of Phillis Wheatley, p. 33.

- "George Washington to Phillis Wheatley, February 28, 1776". The George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741–1799.

- Lakewood Public Library.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- Linda Wilson Fuoco, "Dual success: Robert Morris opens building, reaches fundraising goal", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 27, 2012.

- "UMass Boston Professors To Discuss Phillis Wheatley Saturday Before Theater Performance". UMass Boston.

- "Phillis Wheatley". Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

- "Nubian Jak unveils plaque to Phillis Wheatley 16 July", History & Social Action News and Events, 5 July 2019.

- "Phyllis Wheatley – blue plaque unveiling 16 July 2019", African Century Journal, 16 July 2019.

- "‘Exhume Those Stories: Dramatising African-British Historical Figures’ with Phillis Wheatley and John Blanke, by Greenwich Book Festival", Meeting of Minds UK, 25 May 2018.

Further reading

- Primary materials

- Wheatley, Phillis (1988). John C. Shields, ed. The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506085-7

- Wheatley, Phillis (2001). Vincent Carretta, ed. Complete Writings. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-042430-X

- Biographies

- Borland, (1968). Phillis Wheatley: Young Colonial Poet. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Carretta, Vincent (2011). Phillis Wheatley: Biography of A Genius in Bondage Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3338-0

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (2003). The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America's First Black Poet and Her Encounters With the Founding Fathers, New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01850-5

- Richmond, M. A. (1988). Phillis Wheatley. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 1-55546-683-4

- Secondary materials

- Abcarian, Richard and Marvin Klotz. "Phillis Wheatley," In Literature: The Human Experience, 9th edition. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2006: 1606.

- Bassard, Katherine Clay (1999). Spiritual Interrogations: Culture, Gender, and Community in Early African American Women's Writing. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01639-9

- Engberg, Kathrynn Seidler, The Right to Write: The Literary Politics of Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 2009. ISBN 978-0-761-84609-3

- Langley, April C. E. (2008). The Black Aesthetic Unbound: Theorizing the Dilemma of Eighteenth-century African American Literature. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-1077-2

- Ogude, S. E. (1983). Genius in Bondage: A Study of the Origins of African Literature in English. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: University of Ife Press. ISBN 978-136-048-8

- Reising, Russel J. (1996). Loose Ends: Closure and Crisis in the American Social Text. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1887-3

- Robinson, William Henry (1981). Phillis Wheatley: A Bio-bibliography. Boston: GK Hall. ISBN 0-8161-8318-X

- Robinson, William Henry (1982). Critical Essays on Phillis Wheatley. Boston: GK Hall. ISBN 0-8161-8336-8

- Robinson, William Henry (1984). Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-9346-1

- Shockley, Ann Allen (1988). Afro-American Women Writers, 1746-1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide. Boston: GK Hall. ISBN 0-452-00981-2

External links

| Library resources about Phillis Wheatley |

| By Phillis Wheatley |

|---|

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Phillis Wheatley |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phillis Wheatley. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Phillis Wheatley |

- Works by Phillis Wheatley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Phillis Wheatley at Internet Archive

- Works by Phillis Wheatley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Phillis Wheatley at Open Library

- "Phillis Wheatley" National Women's History Museum

- Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University: Phillis Wheatley collection, 1757-1773