Dred Scott v. Sandford

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court held that the Constitution of the United States was not meant to include American citizenship for black people, regardless of whether they were enslaved or free, and therefore the rights and privileges it confers upon American citizens could not apply to them.[2][3] The decision was made in the case of Dred Scott, an enslaved black man whose owners had taken him from Missouri, which was a slave-holding state, into the Missouri Territory, most of which had been designated "free" territory by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. When his owners later brought him back to Missouri, Scott sued in court for his freedom, claiming that because he had been taken into "free" U.S. territory, he had automatically been freed, and was legally no longer a slave. Scott sued first in Missouri state court, which ruled that he was still a slave under its law. He then sued in U.S. federal court, which ruled against him by deciding that it had to apply Missouri law to the case. He then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

| Dred Scott v. Sandford | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued February 11–14, 1856 Reargued December 15–18, 1856 Decided March 6, 1857 | |

| Full case name | Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford[1] |

| Citations | 60 U.S. 393 (more) 19 How. 393; 15 L. Ed. 691; 1856 WL 8721; 1857 U.S. LEXIS 472 |

| Decision | Opinion |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for defendant, C.C.D. Mo. |

| Holding | |

Judgment reversed and suit dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.

| |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Taney, joined by Wayne, Catron, Daniel, Nelson, Grier, Campbell |

| Concurrence | Wayne |

| Concurrence | Catron |

| Concurrence | Daniel |

| Concurrence | Nelson, joined by Grier |

| Concurrence | Grier |

| Concurrence | Campbell |

| Dissent | McLean |

| Dissent | Curtis |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. V; U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 2;; Missouri Compromise | |

Superseded by | |

| U.S. Const. amends. XIII, XIV, XV; Civil Rights Act of 1866 | |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision against Dred Scott. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court ruled that black people "are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States." Taney supported his ruling with an extended survey of American state and local laws from the time of the Constitution's drafting in 1787 purporting to show that a "perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery." Because the Court ruled that Scott was not an American citizen, any federal lawsuit he filed automatically failed because he could never establish the "diversity of citizenship" that Article III of the U.S. Constitution requires for an American federal court to be able to exercise jurisdiction over a case.[2] After ruling on these issues surrounding Scott, Taney continued further and struck down the entire Missouri Compromise as a limitation on slavery that exceeded the U.S. Congress's powers under the Constitution.

Although Chief Justice Taney and several of the other justices hoped that the ruling would permanently settle the slavery controversy—which was increasingly dividing the American public—its effect was almost the complete opposite.[4] Taney's majority opinion "was greeted with unmitigated wrath from every segment of the United States except the slave holding states,"[3] and the decision was a contributing factor in the outbreak of the American Civil War four years later in 1861. After the Union's victory in 1865, the Court's rulings in Dred Scott were superseded by direct amendments to the U.S. Constitution: the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed citizenship for "all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof".

The Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford is widely denounced by contemporary scholars. Bernard Schwartz says it "stands first in any list of the worst Supreme Court decisions—Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes called it the Court's greatest self-inflicted wound."[5] Junius P. Rodriguez says it is "universally condemned as the U.S. Supreme Court's worst decision."[6] Historian David Thomas Konig says it was "unquestionably, our court's worst decision ever."[7]

Background

Political setting

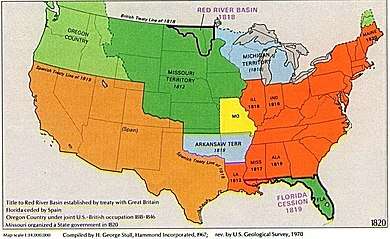

In the late 1810s, a major political dispute arose over the creation of new American states from the vast territory the United States had acquired from France in 1803 through the Louisiana Purchase.[8] The dispute centered on whether the new states would be "free" states like the existing Northern states, in which slavery would be illegal, or whether they would be "slave" states like the existing Southern states, in which slavery would be legal.[8] The Southern states wanted the new states to be slave states in order to enhance their own political and economic power, but the Northern states opposed this for their own political and economic reasons, as well as their moral concerns over allowing the institution of slavery to expand.

In 1820, the U.S. Congress passed an agreement known as the "Missouri Compromise" that was intended to resolve the dispute. The Compromise first admitted Maine into the Union as a free state, then created Missouri out of a portion of the Louisiana Purchase territory and admitted it as a slave state, but at the same time prohibited slavery in the rest of the territory that lay north of the Parallel 36°30′ north, which most of the territory did.[8] The legal effects of a slaveowner taking his slaves from Missouri into the free territory north of the 36°30′ north parallel, as well as the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise itself, eventually came to a head in the Dred Scott case.

Dred Scott and John Emerson

Dred Scott was born a slave in Virginia around 1799[9]. Little is known of his early years.[10] His owner, Peter Blow, moved to Alabama in 1818, taking his six slaves along to work a farm near Huntsville. In 1830, Blow gave up farming and settled in St. Louis, Missouri, where he sold Scott to U.S. Army surgeon Dr. John Emerson.[11] After purchasing Scott, Emerson took him to Fort Armstrong in Illinois. A free state, Illinois had been free as a territory under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, and had prohibited slavery in its constitution in 1819 when it was admitted as a state.

In 1836, Emerson moved with Scott from Illinois to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin territory in what has become the state of Minnesota. Slavery in the Wisconsin Territory (some of which, including Fort Snelling, was part of the Louisiana Purchase) was prohibited by the United States Congress under the Missouri Compromise. During his stay at Fort Snelling, Scott married Harriet Robinson in a civil ceremony by Harriet's owner, Major Lawrence Taliaferro, a justice of the peace who was also an Indian agent. The ceremony would have been unnecessary had Dred Scott been a slave, as slave marriages had no recognition in the law.[12][11]

In 1837, the army ordered Emerson to Jefferson Barracks Military Post, south of St. Louis, Missouri. Emerson left Scott and his wife at Fort Snelling, where he leased their services out for profit. By hiring Scott out in a free state, Emerson was effectively bringing the institution of slavery into a free state, which was a direct violation of the Missouri Compromise, the Northwest Ordinance, and the Wisconsin Enabling Act.[12]

Before the end of the year, the army reassigned Emerson to Fort Jesup in Louisiana, where Emerson married Eliza Irene Sanford in February, 1838. Emerson sent for Scott and Harriet, who proceeded to Louisiana to serve their master and his wife. While en route to Louisiana, Scott's daughter Eliza was born on a steamboat underway on the Mississippi River between Illinois and what would become Iowa. Because Eliza was born in free territory, she was technically born as a free person under both federal and state laws. Upon entering Louisiana, the Scotts could have sued for their freedom, but did not. One scholar suggests that, in all likelihood, the Scotts would have been granted their freedom by a Louisiana court, as it had respected laws of free states that slaveholders forfeited their right to slaves if they brought them in for extended periods. This had been the holding in Louisiana state courts for more than 20 years.[12]

Toward the end of 1838, the army reassigned Emerson to Fort Snelling. By 1840, Emerson's wife Irene returned to St. Louis with their slaves, while Dr. Emerson served in the Seminole War. While in St. Louis, she hired them out. In 1842, Emerson left the army. After he died in the Iowa Territory in 1843, his widow Irene inherited his estate, including the Scotts. For three years after John Emerson's death, she continued to lease out the Scotts as hired slaves. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his and his family's freedom, but Irene Emerson refused, prompting Scott to resort to legal recourse.[13]

Procedural history

|

First attempt

Having been unsuccessful in his attempt to purchase freedom for his family and himself, and with the help of abolitionist legal advisers, Scott sued Emerson for his freedom in a Missouri court in 1846. Scott received financial assistance for his case from the family of his previous owner, Peter Blow.[12] Blow's daughter Charlotte was married to Joseph Charless, an officer at the Bank of Missouri. Charless signed the legal documents as security for Dred Scott and secured the services of the bank's attorney, Samuel Mansfield Bay, for the trial.[11]

Scott based his legal argument on precedents such as Somersett v. Stewart, Winny v. Whitesides,[14] and Rachel v. Walker,[15] claiming his presence and residence in free territories required his emancipation. Scott's lawyers argued the same for Scott's wife, and further claimed that Eliza Scott's birth on a steamboat between a free state and a free territory had made her free upon birth.

It was expected that the Scotts would win their freedom with relative ease, since Missouri courts had previously heard more than ten other cases in which they had freed slaves who had been taken into free territory.[12] Furthermore, the case had been assigned to Judge Alexander Hamilton, who was known to be sympathetic to slave freedom suits.[11] Scott was represented by three lawyers during the course of the case because it was over a year from the time of the original petition filing to the trial. His first lawyer was Francis B. Murdoch, who was replaced by Charles D. Drake. When Drake left St. Louis in 1847, Samuel M. Bay took over as Scott's lawyer.[16] In June 1847, Scott lost his case due to a technicality: Scott had not proven that he was actually enslaved by Irene Emerson. At the trial, grocer Samuel Russell had testified that he was leasing Scott from Irene Emerson, but on cross-examination he admitted that the leasing arrangements had actually been made by his wife Adeline. Thus, Russell's testimony was ruled hearsay and the jury returned a verdict for Emerson.[11]

Scott v. Emerson

In December 1847, Judge Hamilton granted Scott a new trial. Emerson appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Missouri, which affirmed the trial court's order in 1848. Due to a major fire, a cholera epidemic, and two continuances, the new trial did not begin until January 1850. While the case awaited trial, Scott and his family were placed in the custody of the St. Louis County Sheriff, who continued to lease out the services of Scott and his family. The proceeds were placed in escrow, to be paid to Scott's owner or himself upon resolution of the case.

In the 1850 trial, Scott was represented by Alexander P. Field and David N. Hall, both of whom had previously shared offices with Charles Edmund LaBeaume, the brother of Peter Blow's daughter-in-law. The hearsay problem was surmounted by a deposition from Adeline Russell, stating that she had leased the Scotts from Emerson. The jury found in favor of Scott and his family. Unwilling to accept the loss of four slaves and a substantial escrow account, Emerson appealed to the Supreme Court of Missouri, although by that point she had moved to Massachusetts and transferred ownership of Scott to her brother, John F. A. Sanford.

In November 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the trial court's decision, holding that the Scotts were still legally slaves and that they should have sued for freedom while living in a free state. Chief Justice William Scott declared:

Times are not now as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made. Since then not only individuals but States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequences must be the overthrow and destruction of our government. Under such circumstances it does not behoove the State of Missouri to show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit. She is willing to assume her full responsibility for the existence of slavery within her limits, nor does she seek to share or divide it with others.[17]

Scott v. Sanford

At this point, the case looked hopeless, and the Blow family decided that they could no longer pay for Scott's legal costs. Scott also lost both of his lawyers, as Alexander Field had moved to Louisiana and David Hall had died. The case was now undertaken pro bono by Roswell Field, whose office employed Dred Scott as a janitor. Field also discussed the case with LaBeaume, who had taken over the lease on the Scotts in 1851.[18] Following the Missouri Supreme Court decision, Judge Hamilton turned down a request by Emerson's lawyers to release the rent payments from escrow and to deliver the slaves into their owner's custody.[11]

In 1853, Dred Scott again sued his current owner, John Sanford,[1] but now in federal court. Sanford had returned to New York, so the federal courts now had diversity jurisdiction under Article III, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution. In addition to the existing complaints, Scott also alleged that Sanford had assaulted his family and held them captive for six hours on January 1, 1853.[19]

At trial in 1854, Judge Robert William Wells directed the jury to rely on Missouri law to settle the question of Scott's freedom. Since the Missouri Supreme Court had held that Scott remained a slave, the jury found in favor of Sanford. Scott then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the case was recorded as Dred Scott v. Sandford and entered history with that title. Scott was represented before the Supreme Court by Montgomery Blair and George Ticknor Curtis, whose brother Benjamin was a Supreme Court Justice. Sanford was represented by Reverdy Johnson and Henry S. Geyer.[11]

Sanford as defendant

When the case was filed, the two sides agreed on a statement of facts that claimed Scott had been sold by Dr. Emerson to John Sanford. However, this was a legal fiction. Dr. Emerson had died in 1843, and Dred Scott had filed his 1847 suit against Irene Emerson. There is no record of Dred Scott's transfer to Sanford, or of his transfer back to Irene Chaffee. John Sanford died shortly before Scott's manumission, but Scott is not listed in the probate records of Sanford's estate.[18] Nor was Sanford acting as Dr. Emerson's executor, as he was never appointed by a probate court, and the Emerson estate had already been settled by the time the federal case was filed.[12]

Because of the murky circumstances surrounding ownership, it has been suggested that the parties to Dred Scott v. Sandford contrived to create a test case.[13][18][19] Mrs. Emerson's remarriage to an abolitionist Congressman seemed suspicious to contemporaries, and Sanford seemed to be a front who allowed himself to be sued despite not actually being Scott's owner. However, Sanford had been involved in the case since 1847, before his sister married Chaffee. He had secured counsel for his sister in the state case, and he engaged the same lawyer for his own defense in the federal case.[13] Sanford also consented to be represented by genuine pro-slavery advocates before the Supreme Court, rather than putting up a token defense.

Influence of President Buchanan

Historians discovered that after the Supreme Court had heard arguments in the case but before it had issued a ruling, President-elect James Buchanan wrote to his friend, U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice John Catron, asking whether the case would be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court before his inauguration in March 1857.[20] Buchanan hoped the decision would quell unrest in the country over the slavery issue by issuing a ruling that put the future of slavery beyond the realm of political debate.

Buchanan later successfully pressured Associate Justice Robert Cooper Grier, a Northerner, to join the Southern majority in Dred Scott to prevent the appearance that the decision was made along sectional lines.[21] Both by present-day standards and under the more lenient standards of the time, Buchanan's applying such political pressure to a member of a sitting court would be regarded as highly improper.[22] Republicans fueled speculation as to Buchanan's influence by publicizing that Chief Justice Roger B. Taney had secretly informed Buchanan of the decision before Buchanan declared, in his inaugural address, that the slavery question would "be speedily and finally settled" by the Supreme Court.[23][12]

Supreme Court decision

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court ruled against Dred Scott in a 7–2 decision that fills over 200 pages in the United States Reports.[8] The decision contains opinions from all nine justices, but the opinion of the Court—the "majority opinion"—has always been the focus of the controversy.[3]

Opinion of the Court

Seven justices formed the majority and joined an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney. Taney began with a statement of what he saw as the core issue in the case: whether or not black people could possess federal U.S. citizenship under the Constitution.[8]

The question is simply this: Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all of the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guarantied by that instrument to the citizen?

— Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 403.

In answer, the Court ruled that they could not. It held that black people could not be American citizens, and therefore a lawsuit to which they were a party could never qualify for the "diversity of citizenship" that Article III of the United States Constitution requires for an American federal court to be able to exercise jurisdiction over a case.[8] Taney based this holding on a set of historical notions and assertions, and provided little legal reasoning for the Court's conclusions. His primary rationale was his claim that black African slaves and their descendants were never intended to be part of the American social and political landscape.[8]

We think ... that [black people] are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word "citizens" in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time [of America's founding] considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.

— Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 404–05.[24]

Taney then spent many pages reviewing the laws of various American States that involved the status of black Americans at the time of the Constitution's drafting in 1787.[8] He concluded that these laws showed that a "perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery."[25] Thus, he concluded, black people were not American citizens, and could not sue as citizens in federal courts.[8] This meant that U.S. states lacked the power to alter the legal status of black people by granting them state citizenship.[26]

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in relation to that unfortunate race, which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted. ... They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order ...; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.

— Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 407.

Taney concluded that the Court had no jurisdiction over Dred Scott's case because he was not a citizen. However, after deciding this issue, Taney did not conclude the matter before the Court, as per usual procedure, but rather continued further and struck down the Missouri Compromise as unconstitutional.[8] Taney wrote that the Compromise's legal provisions would free slaves who were living north of the 36°N latitude line in the western territories. However, in the Court's judgment, this would constitute the government depriving slaveowners of their property—since slaves were legally the property of their owners—without due process of law, which is forbidden under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[27] Taney also reasoned that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights implicitly precluded any possibility of constitutional rights for black African slaves and their descendants.[26] Thus, Taney concluded:

Now, ... the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. ... Upon these considerations, it is the opinion of the court that the act of Congress which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning property of this kind in the territory of the United States north of the [36°N 36' latitude] line therein mentioned, is not warranted by the Constitution, and is therefore void.

— Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 451–52.

Because the Compromise exceeded the scope of Congress's powers and was unconstitutional, Taney wrote, Dred Scott was still a slave regardless of his time spent in the parts of the Northwest Territory that were north of 36°N and did not allow slavery.[28] Therefore, he was still a slave under Missouri law, and the Court had to follow Missouri law in the matter. For all these reasons, the Court concluded, Dred Scott could not bring suit in U.S. federal court.[28]

Dissents

Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis dissented from the Court's decision, and stated that there was no basis for Taney's claim that blacks could not be citizens. At the time of the ratification of the Constitution, black men could vote in five of the thirteen states. This made them citizens not only of their states but of the United States.[29] Therefore, Justice Curtis concluded that the argument that Scott was not a citizen was "more a matter of taste than of law". In his dissent, Justice Curtis cited as precedent Marie Louise v. Marot, an 1835 case in which Louisiana Supreme Court Chief Justice George Mathews Jr. ruled that "being free for one moment in France, it was not in the power of her former owner to reduce her again to slavery."[30]

Justice John McLean also dissented from the Court's decision, and attacked much of the Supreme Court's decision as obiter dicta that was not legally authoritative, on the ground that once the court determined that it did not have jurisdiction to hear Scott's case, it must simply dismiss the action, and not pass judgment on the merits of the claims. The dissents by Curtis and McLean also attacked the court's overturning of the Missouri Compromise on its merits, noting both that it was not necessary to decide the question, and also that none of the authors of the Constitution had ever objected on constitutional grounds to the United States Congress' adoption of the antislavery provisions of the Northwest Ordinance passed by the Continental Congress, or the subsequent acts that barred slavery north of 36°30' N.

Reaction

Chief Justice Taney's majority opinion in Dred Scott was "greeted with unmitigated wrath from every segment of the United States except the slave holding states."[3] Taney and the other justices did not foresee the extreme public reaction against the decision.[28] In his history of the Supreme Court, the American political historian Robert G. McCloskey (1916–1969) wrote of the Dred Scott decision:

The tempest of malediction that burst over the judges seems to have stunned them; far from extinguishing the slavery controversy, they had fanned its flames and had, moreover, deeply endangered the security of the judicial arm of government. No such vilification as this had been heard even in the wrathful days following the Alien and Sedition Acts. Taney’s opinion was assailed by the Northern press as a wicked “stump speech” and was shamefully misquoted and distorted. “If the people obey this decision," said one newspaper, "they disobey God."

— Robert G. McCloskey (2010), The American Supreme Court, revised by Sanford Levinson (5th ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 62.[31]

Many Republicans—including Abraham Lincoln, who was rapidly becoming the leading Republican in Illinois—regarded the decision as part of a plot to expand and eventually impose nationwide legalized slavery throughout all States.[32] At the same time, Southern Democrats characterized Republicans as lawless rebels, provoking disunion by their unwillingness to accept the Supreme Court's decision as the law of the land. Many Northern opponents of slavery offered a legalistic argument for refusing to recognize the Dred Scott decision as binding. As they noted, the Supreme Court's decision began with the proposition that the federal courts did not have jurisdiction to hear Scott's case because he was not a citizen of the State of Missouri. Therefore, the opponents argued, the remainder of the decision concerning the Missouri Compromise was unnecessary (i.e., beyond the court's power to decide) and therefore a passing remark rather than an authoritative interpretation of the law (i.e., obiter dictum). Douglas attacked this position in the Lincoln–Douglas debates:

Mr. Lincoln goes for a warfare upon the Supreme Court of the United States, because of their judicial decision in the Dred Scott case. I yield obedience to the decisions in that court—to the final determination of the highest judicial tribunal known to our constitution.

Democrats had previously refused to accept the court's interpretation of the Constitution as permanently binding. During the Jackson administration, Roger B. Taney, working as Attorney General, wrote:

Whatever may be the force of the decision of the Supreme Court in binding the parties and settling their rights in the particular case before them, I am not prepared to admit that a construction given to the constitution by the Supreme Court in deciding any one or more cases fixes of itself irrevokably [sic] and permanently its construction in that particular and binds the states and the Legislative and executive branches of the General government, forever afterwards to conform to it and adopt it in every other case as the true reading of the instrument although all of them may unite in believing it erroneous.[33]

Frederick Douglass, a prominent African-American abolitionist who thought the decision unconstitutional and the Chief Justice's reasoning contrary to the founders' vision, prophesied that political conflict could not be avoided:

The highest authority has spoken. The voice of the Supreme Court has gone out over the troubled waves of the National Conscience ... [But] my hopes were never brighter than now. I have no fear that the National Conscience will be put to sleep by such an open, glaring, and scandalous tissue of lies ...[34]

The Scott family's fate

Irene Emerson had moved to Massachusetts in 1850 and married Calvin C. Chaffee, a doctor and abolitionist who was elected to Congress on the Know Nothing and Republican tickets. Following the Supreme Court ruling, proslavery newspapers attacked Chaffee as a hypocrite. Chaffee protested that Dred Scott belonged to his brother-in law and that he had nothing to do with Scott's enslavement.[19] Nevertheless, the Chaffees executed a deed transferring the Scott family to Taylor Blow, son of Scott's former owner Peter Blow. Field suggested the transfer to Chaffee as the most convenient way of freeing Scott, as Missouri law required manumitters to appear in person before the court.[19]

Taylor Blow filed the manumission papers with Judge Hamilton on May 26, 1857. The emancipation of Dred Scott and his family was national news and was celebrated in northern cities. Scott worked as a porter in a hotel in St. Louis, where he was a minor celebrity. His wife took in laundry.

Dred Scott died of tuberculosis only 18 months after attaining freedom, on November 7, 1858. Harriet died on June 17, 1876.[11]

Consequences

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

|

|

|

By country or region

|

|

Religion

|

|

|

Related

|

Economic

Perhaps the most immediate business consequence of the decision was to help trigger the Panic of 1857. Economist Charles Calomiris and historian Larry Schweikart discovered that uncertainty about whether the entire West would suddenly become either slave territory or engulfed in combat like "Bleeding Kansas" gripped the markets immediately. The east–west railroads collapsed immediately (although north–south-running lines were unaffected), causing, in turn, the near-collapse of several large banks and the runs that ensued. What followed these runs has been called the Panic of 1857.

It differed sharply from the Panic of 1837, in that its effects were almost exclusively confined to the North. Calomiris and Schweikart found this resulted from the South's superior system of branch banking (as opposed to the North's unit banking system), in which the transmission of the panic was minor due to the diversification of the southern branch banking systems. Information moved reliably among the branch banks, whereas in the North, the unit banks (competitors) seldom shared such vital information.[35]

Political

The decision was hailed in Southern slaveholding society as a proper interpretation of the United States Constitution. According to Jefferson Davis, then a United States Senator from Mississippi, and later President of the Confederate States of America, the Dred Scott case was merely a question of "whether Cuffee should be kept in his normal condition or not".[36] At that time, "Cuffee" was a common slave name and there often used to refer to a black person, as slavery was a racial caste.[37]

Prior to Dred Scott, Democratic Party politicians had sought repeal of the Missouri Compromise. They were finally successful in 1854 with the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. This act permitted each newly admitted state south of the 40th parallel to vote as to whether to be a slave state or free state. With Dred Scott, the Supreme Court under Taney permitted the unhindered expansion of slavery into all the territories.

The Dred Scott decision, then, represented a culmination of what many at that time considered a push to expand slavery. Southerners at the time, who had grown uncomfortable with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, argued that they had a right, under the federal constitution, to bring slaves into the territories, regardless of any decision by a territorial legislature on the subject. The Dred Scott decision seemed to endorse that view. The expansion of slavery into the territories and resulting admission of new states would mean a loss of political power for the North, as many of the new states would be admitted as slave states. Counting three-fifths of the slave population for apportionment would add to the slave holding states' political representation in Congress.

Although Taney believed that the decision represented a compromise that would settle the slavery question once and for all by transforming a contested political issue into a matter of settled law, it produced the opposite result. It strengthened Northern opposition to slavery, divided the Democratic Party on sectional lines, encouraged secessionist elements among Southern supporters of slavery to make bolder demands, and strengthened the Republican Party.

Later references

Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenting vote in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which declared racial segregation constitutional and created the concept of "separate but equal". In his dissent, Harlan wrote that the majority's opinion would "prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott case".[38]

Charles Evans Hughes, writing in 1927 on the Supreme Court's history, described Dred Scott v. Sandford as a "self-inflicted wound" from which the court would not recover for many years.[39][40][41]

In a memo to Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1952 (for whom he was clerking at the time) on the subject of Brown v. Board of Education, future Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote that "Scott v. Sandford was the result of Taney's effort to protect slaveholders from legislative interference."[42]

Justice Antonin Scalia made the comparison between Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) and Dred Scott in an effort to see Roe v. Wade overturned:

Dred Scott ... rested upon the concept of "substantive due process" that the Court praises and employs today. Indeed, Dred Scott was very possibly the first application of substantive due process in the Supreme Court, the original precedent for ... Roe v. Wade.[43]

Scalia noted that the Dred Scott decision, written and championed by Taney, left the justice's reputation irrevocably tarnished. Taney, while attempting to end the disruptive question of the future of slavery, wrote a decision that aggravated sectional tensions and was considered to contribute to the American Civil War.[44]

Chief Justice John Roberts compared Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to the Dred Scott case, as another example of trying to settle a contentious issue through a ruling that went beyond the scope of the Constitution.[45]

Legacy

- 1977: The Scotts' great-grandson, John A. Madison, Jr., an attorney, gave the invocation at the ceremony at the Old Courthouse (St. Louis) in St. Louis, a National Historic Landmark, for the dedication of a National Historic Marker commemorating the Scotts' case tried there.[46]

- 2000: Harriet and Dred Scott's petition papers in their freedom suit were displayed at the main branch of the St. Louis Public Library, following discovery of more than 300 freedom suits in the archives of the U.S. circuit court.[47]

- 2006: A new historic plaque was erected at the Old Courthouse to honor the active roles of both Dred and Harriet Scott in their freedom suit and the case's significance in U.S. history.[48]

- 2012: A monument depicting Dred and Harriet Scott was erected at the Old Courthouse's east entrance facing the St. Louis' Gateway Arch.[49]

See also

- Anticanon

- American slave court cases

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 60

- List of United States Supreme Court cases

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Privileges and Immunities Clause

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind

- United States labor law

References

Citations

- While the name of the Supreme Court case is Scott vs. Sandford, the respondent's surname was actually "Sanford". A clerk misspelled the name, and the court never corrected the error. Vishneski, John (1988). "What the Court Decided in Dred Scott v. Sandford". The American Journal of Legal History. Temple University. 32 (4): 373–390. doi:10.2307/845743. JSTOR 845743.

- Chemerinsky (2015), p. 722.

- Nowak & Rotunda (2012), §18.6.

- Chemerinsky (2015), p. 723.

- Bernard Schwartz (1997). A Book of Legal Lists: The Best and Worst in American Law. Oxford UP. p. 70.

- Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1.

- David Konig; et al. (2010). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Ohio UP. p. 213.

- Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.1, p. 750.

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dred-Scott

- Earl M. Maltz, Dred Scott and the Politics of Slavery (2007)

- "Missouri's Dred Scott Case, 1846–1857". Missouri Digital Heritage: African American History Initiative. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Finkelman (2007).

- Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (2001)

- 1 Mo. 472, 475 (Mo. 1824).

- 4 Mo. 350 (Mo. 1836). Rachel is remarkable as its fact pattern was on point for Scott's case. Rachel had been a female slave taken into the free Wisconsin Territory by her owner, who was an army officer. In Rachel, the Supreme Court of Missouri held she was free as a consequence of having been taken by her master into a free jurisdiction.

- Ehrlich, Walter (2007). They Have No Rights: Dred Scott's Struggle for Freedom. Applewood Books.

- Scott v. Emerson, 15 Mo. 576, 586 (Mo. 1852) Archived 2013-12-13 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- Ehrlich, Walter (September 1968). "Was the Dred Scott Case Valid?". The Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 55 (2): 256–265. JSTOR 1899556.

- Hardy, David T. (2012). "Dred Scott, John San(d)ford, and the Case for Collusion" (PDF). Northern Kentucky Law Review. 41 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-10.

- Maltz, Earl M. (2007). Dred Scott and the politics of slavery. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 115. ISBN 0-7006-1502-4.

- Faragher, John Mack; et al. (2005). Out of Many: A History of the American People (Revised Printing (4th Ed) ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. p. 388. ISBN 0-13-195130-0.

- Baker, Jean H. (2004). James Buchanan: The American Presidents Series: The 15th President, 1857-1861. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-6946-4.

- "James Buchanan: Inaugural Address. U.S. Inaugural Addresses. 1989". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- Quoted in part in Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.1, p. 750.

- Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.1, p. 750, quoting Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 409.

- Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.6.

- Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.1, pp. 750–51.

- McCloskey (2010), p. 62.

- Abraham Lincoln's Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857 Archived September 8, 2002, at the Wayback Machine.

- Champion of Civil Rights: Judge John Minor Wisdom. Southern Biography Series: LSU Press. 2009. p. 24.

- Quoted in Nowak & Rotunda (2012), §18.6, note 30.

- "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher (1978/2001), The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics, reprint, New York: Oxford, Part 3, "Consequences and Echoes", Chapter 18, "The Judges Judged", p. 441; unpublished opinion, transcript in Carl B. Swisher Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

- Dred Scott vs. Sandford: A Brief History with Documents – Google Boeken.

- Charles Calomiris and Larry Schweikart, "The Panic of 1857: Origins, Transmission, Containment," Journal of Economic History, LI, December 1990, pp. 807–34.

- Speech to the United States Senate, May 7, 1860

- Blassingame, John W. (15 September 2008). "Black New Orleans, 1860-1880". University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 8 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- Fehrenbacher, p. 580.

- Hughes, Charles Evans (1936) [1928]. The Supreme Court of the United States. Columbia University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-231-08567-0.

- "Introduction to the court opinion on the Dred Scott case". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2015-07-16. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Remarks of the Chief Justice". Supreme Court of the United States. March 21, 2003. Retrieved 2007-11-22. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rehnquist, William. "A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases" Archived 2008-09-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992). FindLaw.

- Carey, Patrick W. (April 2002). "Political Atheism: Dred Scott, Roger Brooke Taney, and Orestes A. Brownson". The Catholic Historical Review. The Catholic University of America Press. 88 (2): 207–229. doi:10.1353/cat.2002.0072. ISSN 1534-0708. (requires subscription)

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. (1992).

- Adam Arenson, "Dred Scott versus the Dred Scott Case", The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law, Ohio University Press, 2010, p.36

- Arenson (2010), Dred Scott Case, p. 38

- Arenson (2010), Dred Scott Case, p. 39

- Patrick, Robert (August 18, 2015). "St. Louis judges want sculpture to honor slaves who sought freedom here". stltoday.com. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

Attendees get their first look after the unveiling of the new Dred and Harriet Scott statue on the grounds of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis on Friday, June 8, 2012.

Works cited

- Arenson, Adam (2010). "Dred Scott Versus the Dred Scott Case". In Konig, David Thomas; Finkelman, Paul; Bracey, Christopher Alan (eds.). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0821419120.

- Chemerinsky, Erwin (2019). Constitutional Law: Principles and Policies (6th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4548-9574-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ehrlich, Walter (1968). "Was the Dred Scott Case Valid?". The Journal of American History. 55 (2): 256–265. JSTOR 1899556.

- Finkelman, Paul (2007). "Scott v. Sandford: The Court's Most Dreadful Case and How it Changed History" (PDF). Chicago-Kent Law Review. 82 (3): 3–48.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, Charles Evans (1936) [1928]. The Supreme Court of the United States. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-08567-0.

- McCloskey, Robert G. (2010). The American Supreme Court. Revised by Sanford Levinson (5th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-55686-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nowak, John E.; Rotunda, Ronald D. (2012). Treatise on Constitutional Law: Substance and Procedure (5th ed.). Eagan, Minnesota: West Thomson/Reuters. OCLC 798148265.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Dennis-Jonathan Mann & Kai Purnhagen: The Nature of Union Citizenship between Autonomy and Dependency on (Member) State Citizenship – A Comparative Analysis of the Rottmann Ruling, or: How to Avoid a European Dred Scott Decision?, in: 29:3 Wisconsin International Law Journal (WILJ), (Fall 2011), pp. 484–533 (PDF).

- Fehenbacher, Don E., The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics New York: Oxford (1978) [winner of Pulitzer Prize for History].

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. Slavery, Law, and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective (1981) [abridged version of The Dred Scott Case].

- Konig, David Thomas, Paul Finkelman, and Christopher Alan Bracey, eds. The "Dred Scott" Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law (Ohio University Press; 2010) 272 pages; essays by scholars on the history of the case and its afterlife in American law and society.

- Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861 (1976) pp 267–96.

- VanderVelde, Lea. Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery's Frontier (Oxford University press, 2009) 480 pp.

- Swain, Gwenyth (2004). Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Freedom. Saint Paul, MN: Borealis Books. ISBN 978-0-87351-482-8.

- Tushnet, Mark (2008). I Dissent: Great Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 31–44. ISBN 978-0-8070-0036-6.

- Listen to: American Pendulum II – http://one.npr.org/i/555247859:555247861

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dred Scott v. Sandford |

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- "Dred Scott Case". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Text of Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) is available from: Cornell Findlaw Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist Oyez (oral argument audio)

- The Dred Scott decision. Opinion of Chief Justice Taney, with an introduction by Dr. J. H. Van Evrie. Also, an appendix, containing an essay on the natural history of the prognathous race of mankind, originally written for the New York Day-book, by Dr. S. A. Cartwright, of New Orleans. New York: Van Evrie, Horton & Co. 1863.

- Primary documents and bibliography about the Dred Scott case, from the Library of Congress

- "Dred Scott decision", Encyclopædia Britannica 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 17 December 2006. www.yowebsite.com

- Gregory J. Wallance, "Dred Scott Decision: The Lawsuit That Started The Civil War", History.net, originally in Civil War Times Magazine, March/April 2006

- Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, National Park Service

- Infography about the Dred Scott Case

- The Dred Scott Case Collection, Washington University in St. Louis

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- Dred Scott case articles from William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper The Liberator

- "Supreme Court Landmark Case Dred Scott v. Sandford" from C-SPAN's Landmark Cases: Historic Supreme Court Decisions

- Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott Versus John F.A. Sandford. December Term, 1856 via Google Books