Pet Sounds

Pet Sounds is the eleventh studio album by the American rock band the Beach Boys, released May 16, 1966 on Capitol Records. It initially met with a lukewarm critical and commercial response in the United States, peaking at number 10 on Billboard Top LPs chart, lower than the band's preceding albums. In the United Kingdom, the album was hailed by critics and peaked at number 2 in the UK Top 40 Albums Chart, remaining among the top ten positions for six months. Promoted as "the most progressive pop album ever", Pet Sounds attracted recognition for its ambitious recording and sophisticated music. It is widely considered to be among the most influential albums in the history of music.[1]

| Pet Sounds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | May 16, 1966 | |||

| Recorded | July 12, 1965 – April 13, 1966 | |||

| Studio | United Western Recorders, Gold Star Studios, CBS Columbia Square, and Sunset Sound Recorders, Hollywood | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 35:57 | |||

| Label | Capitol | |||

| Producer | Brian Wilson | |||

| The Beach Boys chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Pet Sounds | ||||

| ||||

The album was produced, arranged, and almost entirely composed by Brian Wilson with guest lyricist Tony Asher. It was mostly recorded between January and April 1966, a year after Wilson quit touring with his bandmates. His goal was to create "the greatest rock album ever made"—a cohesive work with no filler tracks. It is sometimes considered a Wilson solo album and a refinement of the themes and ideas he introduced with The Beach Boys Today! (1965). Lead single "Caroline, No" was issued as his official solo debut. It was followed by two singles credited to the group: "Sloop John B" and "Wouldn't It Be Nice" (backed with "God Only Knows").

Wilson's Wall of Sound-based orchestrations mixed conventional rock set-ups with elaborate layers of vocal harmonies, found sounds, and instruments never before associated with rock, such as bicycle bells, French horn, flutes, Electro-Theremin, string sections, and beverage cans. The album consists mainly of introspective songs like "I Know There's an Answer", a critique of LSD users, and "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times", the first use of a theremin-like instrument on a rock record. Its unprecedented total production cost exceeded $70,000 (equivalent to $550,000 in 2019). In October, the leftover song "Good Vibrations" followed as a single and became a worldwide hit. In 1997, a "making-of" version of Pet Sounds was overseen by Wilson and released as The Pet Sounds Sessions, containing the album's first true stereo mix.

Pet Sounds is regarded by musicologists as an early concept album that advanced the field of music production, introducing non-standard harmonies and timbres, and incorporating elements of pop, jazz, exotica, classical, and the avant-garde. The album could not be replicated live and was the first time a group departed from the usual small-ensemble electric rock band format for a whole LP. Combined with its innovative music, which was perceived as a wholly self-conscious artistic statement (or "concept"), the record furthered the cultural legitimization of popular music, was crucial to the development of progressive/art rock, and helped bring psychedelic music to the mainstream. In 2003 and 2012, Rolling Stone ranked Pet Sounds second on its lists of the greatest albums of all time. In 2004, it was preserved in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Background

The July 1964 release of the Beach Boys' sixth album All Summer Long marked an end to the group's beach-themed period. From there on, their recorded material took a significantly different stylistic and lyrical path.[2] While on a December 23 flight from Los Angeles to Houston, the band's songwriter and producer Brian Wilson suffered a panic attack only hours after performing with the group on the musical variety series Shindig! [3] The 22-year-old Wilson had already skipped several concert tours by then, but the airplane episode proved devastating to his psyche.[4] To focus his efforts on writing and recording, Wilson indefinitely resigned from live performances.[3][5] Freed from the burden, he immediately showcased the advances in his musical development evident within the albums The Beach Boys Today! and Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!), released in the first half of 1965.[6]

With the July 1965 single "California Girls", Wilson began experimenting with song composition while under the influence of psychedelic drugs,[7] a factor that yielded a great effect on the group's musical conceptions.[8][9] During early 1965, he had what he considered to be "a very religious experience" after consuming a full dose of LSD. He stated, "I learned a lot of things, like patience, understanding. I can't teach you, or tell you what I learned from taking it."[10] A week after his first LSD trip, he began suffering from auditory hallucinations, which have persisted throughout his life.[11] Wilson also stated: "I wrote Pet Sounds on marijuana—not on it, but I utilized marijuana now and then for Pet Sounds. ... It gave me the ability—carte blanche—to create something, you know what I mean? And that's where it's at; drugs aren't where it's at. But, for me, that's where it was at in 1966."[12]

At the suggestion of bandmate Al Jardine, Wilson began working on "Sloop John B", a traditional Caribbean folk song that Jardine had learned from listening to the Kingston Trio.[13] Wilson recorded a backing track on July 12, 1965, but after laying down a rough lead vocal, he set the song aside for some time, concentrating on the recording of what became their next LP, the informal studio jam Beach Boys' Party!, in response to their record company Capitol's request for a Beach Boys album for the Christmas 1965 market.[14] Wilson devoted the last three months of 1965 to polishing the vocals of "Sloop John B" and recording six new original compositions.[15][nb 1] In November 1965, "The Little Girl I Once Knew" was released as a non-album single. A section of the song features total silence, leading to poor airplay where radio stations preferred not to have moments of dead air in the middle of a song. It was the last original Beach Boys song issued before any Pet Sounds tracks.[17]

Writing partnership

In 1965, Wilson met Tony Asher at a recording studio in Los Angeles. Asher was at the time a 26-year-old lyricist and copywriter working in jingles for an advertising agency.[18] The two exchanged ideas for songs, and soon after, Wilson heard of Asher's writing abilities from mutual friends.[18] In December 1965, he contacted Asher about a possible lyric collaboration, wanting to do something "completely different" with someone he had never written with before.[19] Asher accepted the offer, and within ten days, they were writing together.[18] Wilson played some of the music he had recently recorded and gave a cassette to Asher containing the backing track to a piece called "In My Childhood".[18][nb 2] The result of Asher's tryout was eventually retitled "You Still Believe in Me", and the success of the piece convinced Wilson that Asher was the wordsmith he had been looking for.[18] When Wilson was asked why he felt Asher was the right collaborator: "Oh, a lot of reasons. One, I thought he was a cool person. Two, anybody that hung out with [my friend] Loren Schwartz was a very brainy guy, a real verbal type person. I just felt that there was something there that had to be, you know, that really had to be."[16][nb 3]

—Tony Asher[18]

Asher explained that he and Wilson had many lengthy, intimate discussions centered around their "experiences and feelings about women and the various stages of relationships and so forth".[18] He maintains that his contribution to the music itself was minimal, serving mainly as a source of second opinion for Wilson as he worked out possible melodies and chord progressions, although the two did trade ideas as the songs evolved.[18] Contrary to the popular conception that Wilson composed all of the music to Pet Sounds, Asher claimed that he also made significant musical contributions to "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times", "Caroline, No", and "That's Not Me".[22] On his role as co-lyricist, he said, "The general tenor of the lyrics was always his ... and the actual choice of words was usually mine. I was really just his interpreter."[23]

Wilson wrote with Asher for about three weeks.[24] A typical writing session started either with Wilson's playing melody or chord patterns that he was working on, by discussing a recent record that Wilson liked the feel of, or by discussing a subject that Wilson had always wanted to write a song about.[18] On "God Only Knows", Wilson reflected: "I think Tony had a musical influence on me somehow. After about ten years, I started thinking about it deeper ... because I had never written that kind of song. And I remember him talking about 'Stella by Starlight' and he had a certain love for classic songs."[16][nb 4] Asher looked back on his interactions with Wilson and the Beach Boys as an "embarrassing" experience, remembering that Wilson "exhibit[ed] this awful taste. His choice of movies, say, was invariably terrible. ... every four hours we'd spend writing songs, there'd be about 48 hours of these dopey conversations about some dumb book [about mysticism] he'd just read. Or else he'd just go on and on about girls."[26] In these discussions, Wilson opened up about personal turmoils that included doubts about his marriage, "sexual fantasies", and "his apparent need to get with [his sister-in-law] Diane."[27][nb 5]

While most of the album's songs derived from the Wilson–Asher partnership, "I Know There's an Answer" was co-written by Wilson with another new associate, the Beach Boys' road manager Terry Sachen.[28][29][30] In 1994, Mike Love was awarded co-writing credits on "Wouldn't It Be Nice" and "I Know There's an Answer",[31] but with the exception of his co-credit on "I'm Waiting for the Day", a song which had been written some two years earlier,[28] his songwriting contributions are thought to have been minimal.[28][nb 6]

Concept and inspiration

Commentators and historians frequently cite Pet Sounds as a concept album, and sometimes as the first concept album in the history of rock music.[32] Academic Carys Wyn Jones attributes this to the album's "uniform excellence" rather than a lyrical theme or musical motif.[33] Even though Pet Sounds has a somewhat unified theme in its emotional content, there was not a predetermined narrative.[34] Asher said that there were no conversations between him and Wilson that pertained to any specific album "concept," however, "that's not to say that he didn't have the capacity to steer it in that direction, even unconsciously."[18] Brian's then-wife Marilyn felt that her relationship with Brian was a central reference within the album's lyrics, namely on "You Still Believe in Me" and "Caroline, No".[35]

For Pet Sounds, Wilson desired to make "a complete statement", similar to what he believed the Beatles had done with their newest album Rubber Soul, released in December 1965.[33][nb 7] Wilson was impressed that the album appeared to lack filler tracks, a feature that was mostly unheard of at a time when 45 rpm singles were considered more noteworthy than full-length LPs.[38][39] Many albums up until the mid-1960s lacked a cohesive artistic goal and were largely used to sell singles at a higher price point.[38][nb 8] Wilson found that Rubber Soul subverted this by having a wholly consistent thread of music.[38][39][nb 9] Inspired, he rushed to his wife and proclaimed, "Marilyn, I'm gonna make the greatest album! The greatest rock album ever made!"[42] He would say of his reaction to Rubber Soul: "I liked the way it all went together, the way it was all one thing. It was a challenge to me ... It didn't make me want to copy them but to be as good as them. I didn't want to do the same kind of music, but on the same level."[43][nb 10]

Wilson's other aspiration for Pet Sounds was to "extend" the music of Phil Spector. He explained that "in one sense of the word, we [the Beach Boys] were his messengers,"[44] and that "If you take the Pet Sounds album as a collection of art pieces, each designed to stand alone, yet which belong together, you'll see what I was aiming at. ... It wasn't really a song concept album, or lyrically a concept album; it was really a production concept album."[45] Author Michael Zager wrote that Pet Sounds resembles Spector's productions more than it does Rubber Soul, and that it recycles many of Spector's Wall of Sound production watermarks.[46] Wilson talked of Spector's influence on his work, having learned how to produce records through attending his sessions,[44] and added that the album may be considered his own "interpretation" of Spector's Wall of Sound.[47] He said that he was especially fascinated by the process of combining sounds "to make another" and sought to emulate those aspects of Spector's productions.[48]

Other influences, according to Wilson, were Burt Bacharach,[49] Les Baxter ("who did all these big productions that sounded sort of like Phil Spector productions"),[50] and Nelson Riddle (who taught him "a lot about arranging").[51] Alternately, when asked if he was a fan of Baxter, Martin Denny, or exotica music in a 2017 interview, he responded: "No, I never get the chance to listen to them. Never did."[52][nb 11] Shortly before the album's release, Wilson spoke of recent popular music trends, saying that they "helped the Beach Boys evolve. We listen to what's happening and it affects what we do too. The trends have influenced my work, but so has my own scene."[53] In 1996, he said of his partnership with Asher: "none of us looked back ... We went forward, kind of like on our own little wavelength. It wasn't like we were thinking, 'Okay, let's beat Spector,' let's out-do Motown.' It was more what I would call exclusive collaboration not to specifically try to kick somebody's butt, but just to do it the way you really want it to be. That's what I thought we did."[16]

Group infighting

Pet Sounds is sometimes considered a Brian Wilson solo album in all but name.[54][55][56] He explained: "Pet Sounds was something that was absolutely different. Something I personally felt. That one album that was really more me than Mike Love and the surf records and all that, and "Kokomo". That's all their kind of stuff, you know?"[16] When the other Beach Boys returned from a three-week tour of Japan and Hawaii, they were presented with a substantial portion of a new album, with music that was in many ways a jarring departure from their earlier style.[57][nb 12] According to various reports, the group fought over the new direction.[59][60] Dennis Wilson denied that the band disagreed with Brian's direction on Pet Sounds, calling the rumors "interesting," saying that there was "not one person in the group that could come close to Brian's talent," and that he "couldn't imagine who" would have resisted Brian's leadership.[61]"[62]

One of the issues was the album's complexity and how the touring Beach Boys could perform its music live.[63] Wilson said that the band wanted to keep the music simple, "and I said 'No, we've gotta grow, guys'."[64] He recalled that the group "liked [the new music] but they said it was too arty. I said, 'No, it is not!"[65] Marilyn said: "When Brian was writing Pet Sounds, it was difficult for the guys to understand what he was going through emotionally and what he wanted to create. ... they didn't feel what he was going through and what direction he was trying to go in."[66] Tony Asher remembered: "All those guys in the band, certainly Al, Dennis, and Mike, were constantly saying, 'What the fuck do these words mean?' or 'This isn't our kind of shit!' Brian had comebacks, though. He'd say, 'Oh, you guys can't hack this.'... But I remember thinking that those were tense sessions."[67]

Mike Love said "some of the words were so totally offensive to me that I wouldn't even sing 'em because I thought it was too nauseating."[69] The original lyrics of "I Know There's an Answer", known as "Hang On to Your Ego", created a stir within the group. He opposed the song's original message, though Jardine recalled that the decision to change the lyrics was ultimately Brian's: "Brian was very concerned. He wanted to know what we thought about it. To be honest, I don't think we even knew what an ego was ... Finally Brian decided, 'Forget it. I'm changing the lyrics. There's too much controversy.'"[28][nb 13] On Love's reaction to the album, Jardine commented: "Mike was very confused ... Mike's a formula hound – if it doesn't have a hook in it, if he can't hear a hook in it, he doesn't want to know about it. ... I wasn't exactly thrilled with the change, but I grew to really appreciate it as soon as we started to work on it. It wasn't like anything we'd heard before."[71] Carl Wilson said: "I loved every minute of it. He [Brian] could do no wrong. He could play me anything, and I would love it."[72] Brian remembered that Carl was enthused with the album, but not Dennis and Mike.[73]

In defense of Love, Asher said that "he never was critical about what [the album] was, he was just saying it wasn't right for the Beach Boys."[74] Brian believed the band was worried about him separating from the group, and elaborated: "it was generally considered that the Beach Boys were the main thing ... with Pet Sounds, there was a resistance in that I was doing most of the artistic work on it vocally".[75] Love wrote: "I also would have liked to have had a greater hand in some of the songs and been able to incorporate more often my 'lead voice,' which we'd had so much success with."[76] The conflicts were resolved, according to Brian, "[when] they figured that it was a showcase for Brian Wilson, but it's still the Beach Boys. In other words, they gave in. They let me have my little stint."[75]

Music and lyrics

The album's soundscape incorporates elements of pop, jazz, classical, exotica, and avant-garde music. According to biographer Jon Stebbins, "Brian defies any notion of genre safety ... There isn't much rocking here, and even less rolling. Pet Sounds is at times futuristic, progressive, and experimental. ... there's no boogie, no woogie, and the only blues are in the themes and in Brian's voice."[78] Genres attributed to the album include progressive pop,[79][80][nb 14] chamber pop,[83][84][85][86] psychedelic pop,[87][88][89][90] art rock,[91][92][93] psychedelic rock,[94][95][96] baroque pop,[97][98] experimental rock,[99][100] and avant-pop.[101][102] Wilson himself thought of the album as "chapel rock ... commercial choir music. I wanted to make an album that would stand up in ten years."[103][nb 15]

Wilson conceived of experimental arrangements[107] that combined conventional rock set-ups with various exotic instruments, producing new sounds with a rich texture reminiscent of symphonic works layered underneath meticulous vocal harmonics.[39] In total, the number of unique instruments used for each track average to about a dozen.[108][nb 16] Many of those instruments were alien to rock music, including glockenspiel, ukulele, accordion, Electro-Theremin, bongos, harpsichord, violin, viola, cello, trombone, Coca-Cola bottles, and other odd sounds such as barking dogs, trains, and bicycle bells.[109] This kind of selection was stylistically appropriated from a wide variety of cultures in a similar fashion to the exotica composer Esquivel.[110]

Journalist Alice Bolin writes that Pet Sounds "repeated and perfected" the themes and ideas introduced in the Beach Boys' album Today!, released one year earlier.[111] Author Chris Smith wrote that the complex arrangements and more developed themes of Today! effectively foreshadowed the lush orchestration and maturity of Pet Sounds.[112] Marshall Heiser expressed for The Journal on the Art of Record Production: "Pet Sounds diverges from previous Beach Boys' efforts in several ways: its sound field has a greater sense of depth and 'warmth;' the songs employ even more inventive use of harmony and chord voicings; the prominent use of percussion is a key feature (as opposed to driving drum backbeats); whilst the orchestrations, at times, echo the quirkiness of 'exotica' bandleader Les Baxter, or the 'cool' of Burt Bacharach, more so than [Phil] Spector's teen fanfares."[113][nb 17] Musicologist Daniel Harrison wrote: "In terms of the structure of the songs themselves, there is comparatively little advance from what Brian had already accomplished or shown himself capable of accomplishing. Most of the songs use unusual harmonic progressions and unexpected disruptions of hypermeter, both features that were met in 'Warmth of the Sun' and 'Don't Back Down.'"[115] Journalist Nick Kent felt "Wouldn't It Be Nice" to be "teen angst dialogue" that Wilson had already achieved with "We'll Run Away" the year before. However: "This time Brian Wilson was out to eclipse these previous sonic soap operas, to transform the subject's sappy sentiments with a God-like grace so that the song would become a veritable pocket symphony."[77]

As author James Perone explains, Wilson's compositions include tempo changes, metrical ambiguity, and unusual tone colors that, culturally speaking, separates the album from any pop music of the era. It also adds to "the background tenderness and melancholy—as well as the increased maturity—that ebb and flow throughout Pet Sounds."[117] He specifically touches upon the album's closer "Caroline, No" and its use of wide tessitura changes, wide melodic intervals, and instrumentation which contribute to his belief; also Wilson's compositions and orchestral arrangements which experiment with form and tone colors.[118] Referring to "Wouldn't It Be Nice", Perone recalls that the track sounds "significantly less like a rock band supplemented with auxiliary instrumentation ... than a rock band integrated into an eclectic mix of studio instrumentation."[119] Arranger Paul Mertens believed that although there are string sections on Pet Sounds: "... what's special about that is not that Brian was trying to introduce classical music into rock & roll. Rather, he was trying to get classical musicians to play like rock musicians. He's using these things to make music in the way that he understood, rather than trying to appropriate the orchestra."[120]

The album included two instrumental tracks composed solely by Brian.[117] One of them: the wistful "Let's Go Away for Awhile".[121][122] the other instrumental is the title track, "Pet Sounds". Both titles had been recorded as backing tracks for existing songs, but by the time the album neared completion Wilson had decided that the tracks worked better without vocals.[123] Of "Let's Go Away for Awhile", Perone observes, "There are melodic features but no tune to speak of. As an instrumental composition, this gives the piece an atmospheric feel; however, the exact mood is difficult to define."[117] Of "Pet Sounds", the piece represents the Beach Boys' surf heritage more than any other track on the album with its emphasis on lead guitar, although Perone maintains that it is not really a surf composition, citing its elaborate arrangement involving countless auxiliary percussion parts, abruptly changing textures, and de-emphasis of a traditional rock band drum set.[107]

Themes

For much of Pet Sounds lyrical content, Brian turned inward and probed his deep-seated self-doubts and emotional longings.[124] However, as journalist Liel Leibovitz writes, the resulting album "wasn't Wilson's autobiography or Asher's but rather a collective autobiography of everything we all feel when we ... try and reach out to another human being".[125] Tony Asher explains:

Brian was constantly looking for topics that kids could relate to. Even though he was dealing in the most advanced score-charts and arrangements, he was still incredibly conscious of this commercial thing. This absolute need to relate.[77]

According to reviewer Jim Esch, the opener "Wouldn't It Be Nice" inaugurates and suggests the album's pervasive theme: "fragile lovers buckling under the pressure of external forces they can't control, self-imposed romantic expectations and personal limitations, while simultaneously trying to maintain faith in one other. It is a theme that keeps reverberating sweetly, and hauntingly, throughout Pet Sounds."[126] Carl said: "The disappointment and the loss of innocence that everyone had to go through when they grow up and find everything's not Hollywood are the recurrent themes on that album."[43] Critics Richard Goldstein and Nik Cohn noted incongruity between the album's music and lyrics, where the latter suggested the work to be "sad songs about happiness" while also celebrating loneliness and heartache.[127] In the opinion of Perone, it is the next track, "You Still Believe in Me", which features the first expression of introspective themes that pervade the rest of the album.[119]

Responding to the songwriters' denials of a conscious lyric theme, Nick Kent observed: "[The] album documents the male participant's attempts at coming to terms with himself and the world about him. Each song pinpoints a crisis of faith in love and life: confusion ('That's Not Me'), disorientation (the staggeringly beautiful 'I Just Wasn't Made for These Times'), recognition of love's capricious impermanence ('Here Today') and finally, the grand betrayal of innocence featured in 'Caroline, No'."[128] Conversely, author Scott Schinder wrote that Wilson and Asher crafted an "emotion-charge song cycle that surveyed the emotional challenges accompanying the transition from youth to adulthood."[129] Schinder continues: "Lyrically, Pet Sounds encompassed the loss of innocent idealism ("Caroline, No"), the transient nature of love ("Here Today"), faith in the face of heartbreak ("I'm Waiting for the Day"), the demands and disappointments of independence ("That's Not Me"), the feeling of being out of step with the modern world ("I Just Wasn't Made for These Times"), and the longing for a happy, loving future ("Wouldn't It Be Nice"). The album also featured a series of intimate, hymn-like love songs, "You Still Believe in Me", "Don't Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder)", and "God Only Knows"."[129]

"Then again," Kent says, "bearing in mind this conceptual bent, there are certain incongruous factors about the album's construction. The main one is the inclusion of the hit single 'Sloop John B', as well as of two instrumental pieces."[128] Perone argues, "To the extent that the listener hears 'Let's Go Away for Awhile' as an incomplete piece, it is possible to understand it as a reflection of the alienation—the sense of not quite fitting in—of the bulk of Tony Asher's lyrics in the songs on Pet Sounds."[117] Noting that a sense of self-doubt, concern for the future of a relationship, and melancholy pervades Pet Sounds, Perone claims in reference to "Sloop John B" that the song successfully portrays a sailor who feels "completely out of place in his situation [which] is fully in keeping with the general feeling of disorientation that runs through so many of the songs."[117]

Fussili states that Wilson's tendency to "wander far from the logic of his composition only to return triumphantly to confirm the emotional intent of his work" is repeated numerous times in Pet Sounds, but never to "evoke a sense of unbridled joy" as Wilson recently had with the single "The Little Girl I Once Knew".[130] In the example of "God Only Knows", which contains an ambivalent key and non-diatonic chords,[115] musicologist Philip Lambert cites its "choral fantasy" section to contain complex key changes that elude the listener "for the entire experience—that in fact, the idea of 'key' has itself been challenged and subverted".[131][nb 18] Perone's interpretation also suggests a visceral musical continuity. On the second track "You Still Believe in Me", "One of the high points of the composition and Brian's vocal performance ... is the snaky, though generally descending melodic line on the line 'I want to cry,' his response to the realization that his girlfriend still believes in him despite his past failures." He describes the "stepwise falloff of the interval of a third at the end of each verse" to be a typically "Wilsonian" feature that recurs throughout the album in addition to a "madrigal sigh motif" that can be heard in "That's Not Me", where the motif concludes each line of the verses. This sighing motif appears in the next track, "Don't Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder)", a piece inspired by classical music, and once again in "Caroline, No".[119] For the high-pitched electric bass guitar part in "Here Today", Perone says they bring to mind similar parts in "God Only Knows", culminating in what sounds like the vocal protagonist of "Here Today" warning the protagonist of "God Only Knows" that what he sings stands no chance at longevity. The protagonist's relationship then concludes shortly after "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times", while "Caroline, No" is a rumination in broken love.[107]

Psychedelia

Wilson's response when asked about LSD and "Hang On to Your Ego" was: "I had taken a few drugs, and I had gotten into that kind of thing. I guess it just came up naturally."[16][nb 19] Despite concerns over the song's drug references, the key lyric "they trip through the day and waste all their thoughts at night" was kept for the final version.[134][135] Elsewhere for "Sloop John B", Wilson's lyric change from "this is the worst trip since I've been born" to "this is the worst trip I've ever been on" has also been suggested to be another subtle nod to acid culture.[136][137][138]

The album is often considered within the canon of psychedelic rock.[94] The Encyclopedia Britannica states that the Beach Boys introduced psychedelic elements with the album, calling it "expansive" and "haunting".[139] Writer Vernon Joyson observes flirtations with acid rock.[140] Bret Marcus of Goldmine noted that he believed that the album is psychedelic pop, even though most people hesitate to name the Beach Boys in discussions of psychedelic music.[88] Stebbins writes that the album is "slightly psychedelic—or at least impressionistic."[141] According to academics Paul Hegarty and Martin Halliwell, Pet Sounds has a "personal intimacy" that sets it apart from the Beach Boys' contemporaries in psychedelic culture and the San Francisco Sound, but still retains a "trippy feel" that resulted from Wilson's experimental use of LSD. They attribute this to Wilson's "eclectic mixture of instruments, echo, reverb, and innovative mixing techniques learnt from Phil Spector to create a complex soundscape in which voice and music interweave tightly".[142] Wilson acknowledged that psychedelic elements are present in a number of the songs, but believed "the album itself is mostly not psychedelic".[132]

DeRogatis compared the album's repeated listening value to a heightened psychedelic awareness, that its melodies "continue to reveal themselves after dozens of listens, just as previously unnoticed corners of the world reveal themselves during the psychedelic experience".[143] On the subject of psychedelic records in the 1960s, Sean Lennon stated that "psychedelic music is a term that pretty much refers to these sort of epic, ambitious long-form records ... the reason Pet Sounds is considered a psychedelic journey or whatever is because it's like opening a door and stepping through and entering another world and you're in that other world for a period of time and then you come back."[144]

Recording and production

Backing tracks

Wilson produced several backing tracks over a period lasting several months, using professional Hollywood recording studios and an ensemble that included the classically trained session musicians nicknamed "the Wrecking Crew", also known as the musicians frequently employed on Phil Spector's records.[146][39] Most sessions were conducted at Western Studio 3 of United Western Recorders, with few additional tracking dates at Gold Star Studios and Sunset Sound Recorders.[147] Surviving tapes of his recording sessions show that he was open to his musicians, often taking advice and suggestions from them and even incorporating apparent mistakes if they provided a useful or interesting alternative.[39] Wilson said that he "was sort of a square" with the Wrecking Crew, starting his creative process with how each instrument sounded one-by-one, moving from keyboards, drums, then violins if they were not overdubbed.

Although the self-taught Wilson often had entire arrangements worked out in his head, they were usually written in a shorthand form for the other players by one of his session musicians.[16][nb 20] On notation and arranging, Wilson explained: "Sometimes I'd just write out a chord sheet and that would be for piano, organ, or harpsichord or anything. ... I wrote out all the horn charts separate from the keyboards. I wrote one basic keyboard chart, violins, horns, and basses, and percussion."[16] A backing track session would last for three hours at minimum. Engineer Chuck Britz remembered how most of the time was spent perfecting individual sounds: "[Brian] knew basically every instrument he wanted to hear, and how he wanted to hear it. What he would do is call in all the musicians at one time (which was very costly), but still, that's the way he would do it."[149]

.jpg)

Tape effects were limited to slapback echo and reverb. Archivist Mark Linett notes: "to my ears, it sounds more like the plate [reverberators] rather than chambers. It should be mentioned that you get a significantly different sound from a chamber when you record it 'live' as opposed to doing it off tape, and one reason these records sound the way they do is that the reverb was being printed as part of the recording – unlike today where we'll record 'dry' and add the effects later."[147]

Although Spector's trademark sound was aurally complex, many of the best-known Wall of Sound recordings were recorded on Ampex three-track recorders. Spector's backing tracks were recorded live, and usually in a single take. These backing tracks were mixed live, in mono, and taped directly onto one track of the three-track recorder.[150] The lead vocal was then taped, usually (though not always) as an uninterrupted live performance, recorded direct to the second track of the recorder. The master was completed with the addition of backing vocals on the third track before the three tracks were mixed down to create the mono master tape.[150]

By comparison, Brian produced tracks that were of greater technical complexity by using state-of-the-art four-track and eight-track recorders.[151] Most backing tracks were recorded onto a Scully four-track 288 tape recorder[147] before being later dubbed down (in mono) onto one track of an eight-track machine.[152] Wilson typically divided instruments by three tracks: drums–percussion–keyboard, horns, and bass–additional percussion–guitar. The fourth track usually contained a rough reference mix used during playback at the session, later to be erased for overdubs such as a string section.[151] "Once he had what he wanted," Britz said, "I would give Brian a 7-1/2 IPS [tape] copy of the track, and he would take it home."[153]

Discussing Spector's Wall of Sound technique, Wilson identified the tack piano and organ mix in "I Know There's an Answer" as one example of himself applying the method.[146] Wilson also doubled the bass (typically using an acoustic upright bass and an electric bass), guitars and keyboard parts,[153] blending them with reverberation and adding other unusual instruments.[154] One of Wilson's favorite techniques was to apply reverb exclusively to a timpani, as can be heard in "Wouldn't It Be Nice", "You Still Believe in Me", and "Don't Talk".[155]

Vocals and mixdown

The Beach Boys rarely knew their parts before arriving in the studio. Britz: "Most of the time, they were never ready to sing. They would rehearse in the studio. Actually, there was no such thing as rehearsal. They'd get on mike right off the bat, practically, and start singing."[153] According to Jardine, each member was taught their individual vocal lines by Brian at a piano. He explains, "Every night we'd come in for a playback. We'd sit around and listen to what we did the night before. Someone might say, well, that's pretty good but we can do that better ... We had somewhat photographic memory as far as the vocal parts were concerned so that was never a problem for us."[156] This process proved to be the most exacting work the group had undertaken yet. During recording, Mike Love often called Brian "dog ears", a nickname referencing a canine's ability to detect sounds far beyond the limits of human hearing.[157] Love later summarized:

We worked and worked on the harmonies and, if there was the slightest little hint of a sharp or a flat, it wouldn't go on. We would do it over again until it was right. [Brian] was going for every subtle nuance that you could conceivably think of. Every voice had to be right, every voice and its resonance and tonality had to be right. The timing had to be right. The timbre of the voices just had to be correct, according to how he felt. And then he might, the next day, completely throw that out and we might have to do it over again.[158]

By the time of Pet Sounds, Wilson was using up to six of the eight tracks on the multitrack master so that he could record the voice of each member separately, allowing him greater control over the vocal balance in the final mix.[151] After mixing down the four-track to mono for overdubbing via an eight-track recorder, six of the remaining seven tracks were usually dedicated to each of the Beach Boys' vocals.[151] The last track was usually reserved for additional elements such as extra vocals or instrumentation.[28][nb 21] Vocals were recorded using two Neumann U-47s, which Dennis, Carl and Jardine would sing on, and a Shure 5–35 used by Brian for his leads.[153] Love sang most of the album's bass vocals, and necessitated an extra microphone due to his low volume range.[157] Some of the vocals were recorded at CBS Columbia Square, because it was the only facility in Los Angeles with an eight-track recorder.[147][151]

The album's final vocal overdubbing session took place on April 13, 1966, concluding a ten-month-long recording period that had begun with "Sloop John B" in July 1965.[159] The album was mixed three days later in a single nine-hour session.[56][nb 22] Saxophonist Steve Douglas recalls of the album's draft mix: "It was full of noise. You could hear him talking in the background. It was real sloppy. He had spent all this time making the album, and zip—dubbed it down in one day or something like that. [When we said something to him about it], he took it back and mixed it properly. I think a lot of times, beautiful orchestrated stuff or parts got lost in his mixes".[161] A true stereophonic mix of Pet Sounds was not considered in 1966 largely because of mixing logistics.[151] In spite of whether a true stereo mix was possible, Wilson intentionally mixed the final version of his recordings in mono (as did Spector). He did this because he felt that mono mastering provided more sonic control over the final result, irrespective of the vagaries of speaker placement and sound system quality.[151][nb 23] Another and more personal reason for Brian's preference for mono was his almost total deafness in his right ear.[162][nb 24] The total cost of production amounted to a then-unheard of $70,000 (equivalent to $550,000 in 2019).[127]

Leftover material

On October 15, 1965, Brian went to the studio with a 43-piece orchestra to record an instrumental piece entitled "Three Blind Mice", which bore no musical connection to the nursery rhyme of the same name.[164][nb 25] Another instrumental, called "Trombone Dixie", was recorded. According to Brian, "I was just foolin' around one day, fuckin' around with the musicians, and I took that arrangement out of my briefcase and we did it in 20 minutes. It was nothing, there was really nothing in it."[165][nb 26]

In mid February 1966, Brian was in the studio with his session band taping the first takes of a new composition, "Good Vibrations".[158] On February 23, he gave Capitol a provisional track listing for the new LP, which included both "Sloop John B" and "Good Vibrations".[158] This contradicts the long-held misconception that "Sloop John B" was a forced inclusion as the hit single at Capitol's insistence: in late February, the song was weeks away from release.[158][166] Brian worked through February and into March fine-tuning the backing tracks. To the group's surprise, he also dropped "Good Vibrations" from the running order, telling them that he wanted to spend more time on it. Al Jardine remembered: "At the time, we all had assumed that 'Good Vibrations' was going to be on the album, but Brian decided to hold it out. It was a judgment call on his part; we felt otherwise but left the ultimate decision up to him."[158]

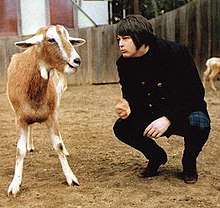

Brian devoted some Pet Sounds sessions to avant-garde indulgences such as an extended a cappella run-through of the children's song "Row, Row, Row Your Boat" that exploited the song's use of rounds. Humorous skits and sound effects were recorded in an attempt to create a psychedelic comedy album, foreshadowing much of his work on Smile, which was set to have followed Pet Sounds. The only product of these sessions present in Pet Sounds was an excerpt of Brian's dogs barking accompanied by a recording of passing trains, which was sampled from the 1963 sound effects LP Mister D's Machine.[164] Brian may also have briefly considered recording other animal sounds for inclusion, as evidenced by a snippet of surviving studio chatter from a "dog barking" session. This features Brian asking Britz: "Hey, Chuck, is it possible we can bring a horse in here without ... if we don't screw everything up?", to which a clearly startled Britz responds, "I beg your pardon?", with Brian then pleading, "Honest to God, now, the horse is tame and everything!"[167]

Title and artwork

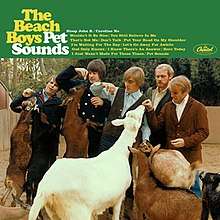

The front sleeve depicts a snapshot of the band – from left, they are Carl, Brian, and Dennis Wilson; Mike Love; and Al Jardine – feeding pieces of apples to seven goats at the zoo.[168][nb 27] The photo was taken on February 10, 1966, when the group traveled to the San Diego Zoo[15] accompanied by the photographer George Jerman.[170] The sleeve's header, written in Cooper Black,[171][172] displays "The Beach Boys Pet Sounds", followed by the album's track list.

Love remembers that Capitol's working title for the album was Our Freaky Friends, and that the label planned the cover shoot at the zoo, with the animals representing the group's "freaky friends".[173][nb 28] In May, the San Diego Union reported that the group "came down from Hollywood to take a cover picture for their forthcoming album Our Freaky Friends. ... Zoo officials were not keen about having their beloved beasts connected with the title of the album, but gave in when the Beach Boys explained that animals are an 'in' thing with teenagers. And that the Beach Boys were rushing to beat the rock and roll group called The Animals."[nb 29] Asher remembered: "[Brian] had some proofs of the pictures they'd done at the zoo, and he told me they were thinking of calling the album Pet Sounds. I thought it was a goofy name for an album – I thought it trivialized what we had accomplished."[175] Until arriving to the photo shoot, Jardine thought that "pet" referred to slang for making out ("petting"). Jardine also expressed disappointment with the chosen cover, believing it was "crazy" to go to the zoo, that "the art department screwed up pretty badly on that one ... [I] wanted a more sensitive and enlightening cover."[176] Author Peter Doggett writes that the design was at odds with the increasingly sophisticated cover portraits used on releases by artists such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan over 1965–67.[177] He highlights it as "a warning of what could happen when music and image parted company: songs of high romanticism, an album cover of stark banality."[177]

The name Pet Sounds was Love's invention, according to himself,[158] Brian,[168] and Jardine.[168] Brian explained that the album was named "after the dogs ... That was the whole idea",[178] and that the title was a "tribute" to Spector by matching his initials (PS),[179] but could not recall who thought of going to the zoo.[168] Love recounted: "We were standing in the hallway in one of the recording studios, either Western or Columbia, and we didn't have a title. ... We had taken pictures at the zoo and ... there were animal sounds on the record, and we were thinking, well, it's our favorite music of that time, so I said, 'Why don't we call it Pet Sounds?'"[158][157] Brian has also credited Carl for the title,[49][158] while Carl said with uncertainty that it might have come from Brian: "The idea he [Brian] had was that everybody has these sounds that they love, and this was a collection of his 'pet sounds.' It was hard to think of a name for the album, because you sure couldn't call it Shut Down Vol. 3 .. It was just so much more than a record; it had such a spiritual quality. It wasn't going in and doing another top ten. It had so much more meaning than that."[72][nb 30]

Release

—Brian Wilson to Melody Maker, March 1966[53]

After the album was assembled, Brian brought a complete acetate to Marilyn, who remembered, "It was so beautiful, one of the most spiritual times of my whole life. We both cried. Right after we listened to it, he said he was scared that nobody was going to like it. That it was too intricate."[66] Pet Sounds was released on May 16, debuting on the Billboard charts at 106.[182] It sold 200,000 copies shortly therafter.[183] Compared to their previous albums in the US, Pet Sounds achieved somewhat less commercial success; it peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard LP chart on July 2,[184] with total sales estimated at around 500,000 units.[185] Pet Sounds' initial release was not awarded gold certification by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). In February 2000, Pet Sounds was presented with gold and platinum awards based on sales that could be documented, although Capitol Records estimated it may have sold over two million copies.[186][187]

Brian was "heartsick" that Pet Sounds didn't sell as highly as he expected, and interpreted the response as a rejection to his creative ideals.[16] Some blamed Capitol Records for the album's underwhelming sales. Allegedly, they did not promote the album as heavily as previous releases.[72][188] Carl stated that Capitol did not feel a need to promote the Beach Boys since they were getting so much airplay, and that they had a "set image" for the group which even Pet Sounds could not alter.[72] Others assumed that the label considered the album a risk, appealing more to an older demographic than the younger, female audience the Beach Boys built their commercial standing on.[189] To Brian's dismay, within two months, Capitol assembled the group's first greatest hits compilation, Best of the Beach Boys, which was quickly certified gold by the RIAA.[190] Capitol executive Karl Engemann later said: "This is just conjecture on my part because it was so long ago ... because the marketing people didn't believe that Pet Sounds was going to do that well, they were probably looking for some additional volume in that quarter. There's a good possibility that's what happened. Anyway, my real forte was dealing with artists and producers and making them feel comfortable so they could achieve their ends. And sometimes, particularly when the label wanted something that the artist didn't, it wasn't easy."[191]

Before Pet Sounds was released, "Caroline, No" was issued as a single; it was credited to Brian alone, leading to speculation that he was considering leaving the band.[192] The single reached number 32 in the US.[193] It was followed by "Sloop John B", credited to the Beach Boys. The single reached number 3 in the US[193] and number 2 in Britain.[194] It had a three-week stay at number 1 in the Netherlands, making it the "Hit of the Year".[195] Two months after the album's release, "Wouldn't It Be Nice" was released, later reaching number 8 in the US, where it was treated as the A-side.[193] Its flip side, "God Only Knows", was featured as the A-side in Europe, peaking at number 2 in Britain.[194] As a B-side in the US, it reached number 39.[193]

United Kingdom EMI release

The album's greatest success was in the UK, where it reached number 2[194] and stayed in the top-ten positions for six months.[196] It was aided by support from the British music industry, who embraced the record. Bruce Johnston stated that when he was in London in May 1966, a number of musicians and other guests gathered in his hotel suite to listen to repeated playbacks of the album. This included John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Keith Moon. Moon himself involved Johnston by helping him gain coverage in British television circuits, and connecting him with Lennon and McCartney.[188] There were initially no plans by EMI to issue the album in the UK.[10] Johnston claimed that Pet Sounds got so much publicity, "it forced EMI to put the album out sooner."[188]

Pet Sounds was released in the UK on June 27.[184] In response to the success of the Beach Boys' singles "Barbara Ann", "Sloop John B." and "God Only Knows" in the UK, EMI flooded the market with other albums by the band, including Beach Boys' Party!, The Beach Boys Today! and Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!)[197] In addition, Best of the Beach Boys was number 2 there for five weeks through to the end of the year.[198] The Beach Boys became the strongest selling album act in the UK for the final quarter of 1966, dethroning the three-year reign of native bands such as the Beatles.[199]

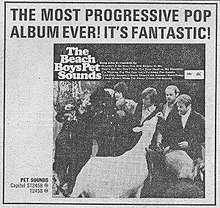

Derek Taylor, the Beach Boys' publicist, is widely recognized as having been instrumental in this success, due to his longstanding connections with the Beatles and other industry figures in the UK.[200] The music press there carried advertisements saying that Pet Sounds was "The Most Progressive Pop Album Ever!"[82][201] Rolling Stone founding editor Jann Wenner later recalled that fans in the UK identified the Beach Boys as being "years ahead" of the Beatles and declared Wilson a "genius"[202] – the latter being a description of the group's leader that Taylor had helped to establish among local music journalists.[203] Carlin writes that Andrew Oldham, the Rolling Stones' manager, took out a full-page advertisement in Melody Maker in which he lauded Pet Sounds as "the greatest album ever made".[204][nb 31]

Two music videos were filmed set to "Sloop John B" and "God Only Knows" for the UK's Top of the Pops, both directed by Taylor. The first was filmed at Brian's Laurel Way home with Dennis acting as cameraman, the second near Lake Arrowhead. While the second film, containing footage of the group minus Bruce flailing around in grotesque horror masks and playing Old Maid, was intended to be accompanied by excerpts from "Wouldn't It Be Nice", "Here Today" and "God Only Knows", slight edits were made by the BBC to reduce the film's length.[206]

Critical reception

Contemporary reviews

Early reviews for the album in the U.S. ranged from negative to tentatively positive.[185] Billboard's reviewer called it an "exciting, well-produced LP" with "two superb instrumental cuts", and highlighted the "strong single potential" of "Wouldn't It Be Nice".[182] By contrast, the reception from music journalists in the UK was highly favourable.[207][208] Penny Valentine of Disc and Music Echo admired it as "Thirteen tracks of Brian Wilson genius ... The whole LP is far more romantic than the usual Beach Boys jollity: sad little wistful songs about lost love and found love and all-around love."[209] Writing in Record Mirror, Norman Jopling reported that the LP had been "widely praised",[210] yet he predicted: "It will probably make their present fans like them even more, but it's doubtful whether it will make them any new ones."[211] A reviewer in Disc and Music Echo disagreed: "this should gain them thousands of new fans. Instrumentally ambitious, if vocally over-pretty, Pet Sounds has brilliantly tapped the pulse of the musical times. ... A superb, important and really exciting collection from the group whose recording career so far has been a bit of a hotchpotch."[184]

Melody Maker ran a feature in which many pop musicians were asked whether they believed that the album was truly revolutionary and progressive, or "as sickly as peanut butter".[184] The author concluded that "the record's impact on artists and the men behind the artists has been considerable."[184] Among the musicians contributing to the 1966 Melody Maker survey, Spencer Davis of the Spencer Davis Group said: "Brian Wilson is a great record producer. I haven't spent much time listening to the Beach Boys before, but I'm a fan now and I just want to listen to this LP again and again."[184] Then a member of Cream, Eric Clapton, reported that everyone in his band loved the album.[184] Andrew Oldham said: "I think that Pet Sounds is the most progressive album of the year in as much as Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade was. It's the pop equivalent of that, a complete exercise in pop music."[184] In other issues of Melody Maker, Mick Jagger stated that he disliked the songs but enjoyed the record and its harmonies, while John Lennon said that Wilson was "doing some very great things".[212]

Three of the nine people who are quoted in the Melody Maker survey (Keith Moon, Manfred Mann's Michael D'Abo, and the Walker Brothers' Scott Walker) did not agree that the album was revolutionary. D'Abo and Walker favored the Beach Boys' earlier work, as did journalist and television presenter Barry Fantoni, who expressed a preference for Beach Boys' Today! and stated that Pet Sounds "[is] probably revolutionary, but I'm not sure that everything that's revolutionary is necessarily good".[213] Pete Townshend of the Who opined that "the Beach Boys new material is too remote and way out. It's written for a feminine audience."[184][nb 32] Writing in Jazz & Pop magazine in 1968, Gene Sculatti recognized the album's debt to Rubber Soul, saying that Pet Sounds was "revolutionary only within the confines of the Beach Boys' music", although later in the piece he commented: "Pet Sounds was a final statement of an era and a prophecy that sweeping changes lay ahead."[215]

Retrospective acclaim and status

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Sun-Times | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A+[221] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Slant Magazine | |

According to author Johnny Morgan, a "process of reevaluation" of Pet Sounds was underway from the late 1960s onward, with a 1976 NME feature proving especially influential.[211] In his 1969 Pop Chronicles series, John Gilliland stated that the album was almost overshadowed by the Beatles' Revolver, released two months later, and that "a lot people failed to realize that Brian Wilson's production was as unique in its own way as the Beatles'".[202] Noel Murray of The A.V. Club, writing in 2014, theorized that the success of "Good Vibrations" helped turn around the perception of Pet Sounds, in that the album's "un-hip orchestrations and pervasive sadness baffled some longtime fans, who didn't immediately get what Wilson was trying to do."[226]

—Stephen Davis in Rolling Stone, June 1972[227]

In a 1972 review for Rolling Stone, Stephen Davis called Pet Sounds "by far" Brian Wilson's best album and said that its "trenchant cycle of love songs has the emotional impact of a shatteringly evocative novel".[227] Writing in the first edition of The Rolling Stone Record Guide (1979), Dave Marsh gave the album four stars (out of a possible five) and described it as a "powerful, but spotty" collection on which the least experimental songs proved to be the best.[228] Five years later, he wrote that the album was now considered a "classic", elaborating: "Pet Sounds wasn't a commercial flop, but it did signal that the group was losing contact with its listeners (a charge that could not be leveled against the Beatles during the same period)".[229]

In Music USA: The Rough Guide, Richie Unterberger and Samb Hicks deem the album to be a "quantum leap" from the Beach Boys' earlier material, and "the most gorgeous arrangements ever to grace a rock record".[230] The New York Observer's D. Strauss says that the album's quality and subversion of rock traditions is "what created its special place in rock history; there was no category for its fans to place it in".[231] Author Luis Sanchez views the album as "the score to a film about what rock music doesn't have to be. For all of its inward-looking sentimentalism, it lays out in a masterful way the kind of glow and sui generis vision that Brian aimed to [later] expand."[167][nb 33]

In Chris Smith's book 101 Albums That Changed Popular Music (2009), Pet Sounds is evaluated as "one of the most innovative recordings in rock" and that it "elevated Brian Wilson from talented bandleader to studio genius".[109] Dominique Leone wrote a 9.4 (out of 10) review of its 40th Anniversary edition for Pitchfork stating: "Certainly, regardless of what I write here, the impact and 'influence' of the record will have been in turn hardly influenced at all. I can't even get my dad to talk about Pet Sounds anymore. ... The hymnal aspect of many of these songs seems no less pronounced, and the general air of deeply heartfelt love, graciousness and the uncertainty that any of it will be returned are still affecting to the point of distraction."[110] Music journalist Robert Christgau felt that Pet Sounds was a good record, but believed it had become looked upon as a totem.[233] Composer Atticus Ross explained that the album has "an element of cliché that's grown around it". He references a sketch from the television show Portlandia in which "your classic hipster musicians ... are building a studio and everything is like 'this is the mike they used in Pet Sounds.' This is exactly the same as Pet Sounds.'"[234] Commentator C.W. Maloney mused: "The songs on Pet Sounds are great, but you have to wonder, given all the hype and mythology and our love of shallow nostalgia, what we mean when we call it a classic or Wilson a genius. Consider what [Frank] Zappa was doing in 1966, to say nothing of Miles [Davis]. Wilson's high reputation is evidence of our obsession with childlike innocence and the victory of boring poptimism."[235]

By the 1990s, three British critics' polls featured Pet Sounds at or near the top of their lists.[236] Those who have deemed it "the greatest album of all time" include NME,[237] The Times,[238] and Uncut.[239] It was voted number 18 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums 3rd Edition (2000).[240] In 1998, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences inducted the album into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[241] In 2004, Pet Sounds was preserved in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[242] As of 2006, more than 100 domestic and international publications and journalists have lauded Pet Sounds as one of the greatest albums ever recorded.[243] It has been viewed by some writers as the best pop rock album of all time,[244] including Tim Sommer who deemed it "the greatest album of all time, probably by about 20 or 30 lengths".[245] As of 2015, Acclaimed Music, which statistically aggregates hundreds of published lists, ranked Pet Sounds as the most acclaimed album of all time.[246] The position was previously held by Revolver and was overtaken by Pet Sounds in 2004.[247]

Influence and legacy

Innovations and scope of impact

—Jeff Straton, New Times Broward-Palm Beach, 2000[248]

Pet Sounds is recognized as an ambitious and sophisticated work that advanced the field of music production in addition to setting numerous precedents in its recording.[249] The album's historical distinctions include being the first piece in popular music to incorporate the Electro-Theremin, an easier-to-play version of the theremin, as well as the first in rock music to feature a theremin-like instrument.[250] The Electro-Theremin's inventor Paul Tanner performs the instrument on the song "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times".[28][251] Pet Sounds was also the first time that a group departed from the usual small-ensemble electric rock band format for an entire album.[252] According to D. Strauss, they were also the first major rock group "to look music trends firmly in the eye and declare that rock really didn't matter. Rock is supposed to be about, you know, fucking, and Brian Wilson was recording a song ('I Know There's an Answer') that was originally entitled 'Get Rid of Your Libido'."[231]

Although not originally a big seller, Pet Sounds has been "enormously" influential since it was released.[109] To explain why the album "was one of the defining moments of its time", composer Philip Glass referred to "its willingness to abandon formula in favor of structural innovation, the introduction of classical elements in the arrangements, [and] production concepts in terms of overall sound which were novel at the time".[253] Perone's assessed that the album's composition was stylistically removed from "just about anything else that was going on in 1966 pop music".[117] Professor of American history John Robert Greene stated that "God Only Knows" remade the ideal of the popular love song, while "Sloop John B" and "Pet Sounds" broke new ground and took rock music away from its casual lyrics and melodic structures into what was then uncharted territory.[254] In 1971, publication Beat Instrumental & International Recording wrote: "Pet Sounds took everyone by surprise. In terms of musical conception, lyric content, production and performance, it stood as a landmark in a music genre whose development was about to begin snowballing."[255] That same year, Cue magazine reflected that "in the year and a half that followed Pet Sounds, the Beach Boys were among the vanguard ... anticipating changes that rock didn't accomplish until 1969–1970."[256]

Thought to be released on the same day as the album was Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde, which Leibovitz called "two strands in the same conversation, the one that turned American popular music, for one fleeting moment of one year in the middle 1960s, into a religious movement".[125] Author Geoffrey Himes said that "Brian's introduction of non-standard harmonies and timbres proved as revolutionary" as Dylan's introduction of "irony into rock'n'roll lyrics".[43] Similar to subsequent experimental rock LPs by Frank Zappa, the Beatles, and the Who, Pet Sounds featured countertextural aspects that called attention to the very recordedness of the album.[257] Paul McCartney frequently spoke of his affinity with the album, citing "God Only Knows" as his favorite song of all time, and crediting his melodic bass-playing style to the album.[258][259] He acknowledged that Pet Sounds was the primary impetus for the Beatles' 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. The interplay between the Beatles and the Beach Boys thus inextricably links the two albums together.[260][nb 34]

Brian's ensuing mythology originated the trope of the "reclusive genius" among studio-oriented musical artists.[40] His father and ex-band manager Murry praised the album, calling it a "masterpiece of accomplishment for Brian", and believed that it was a ubiquitous influence in the music heard in product commercials.[262] In 2016, Jason Guriel of The Atlantic said that Brian "certainly anticipated the modern pop-centric era, which privileges producer over artist and blurs the line between entertainment and art", and drew comparisons with the albums of Michael Jackson, Prince, and Radiohead.[40] Music critic Tim Sommer, referencing other albums that are often labeled "masterpieces", such as OK Computer (1997), The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) or Thick as a Brick (1972), commented that that "only Pet Sounds is written from the teen or adolescent point of view."[252]

In 1995, a panel of numerous musicians, songwriters and producers assembled by MOJO voted Pet Sounds as the greatest album among them.[263] For the album's 50th anniversary, 26 artists contributed to a Pitchfork retrospective on its influence, which included comments from members of Talking Heads, Yo La Tengo, Chairlift, and Deftones. The editor noted that the "wide swath of artists assembled for this feature represent but a modicum of the album’s vast measure of influence. Its scope transcends just about all lines of age, race, and gender. Its impact continues to broaden with each passing generation."[264]

Influence on genres

The album informed the developments of genres such as rock, hip hop, jazz, electronic, experimental, punk, pop,[264] and is often cited as one of the earliest entries in the canon of psychedelic rock.[94] Scholar Philip Auslander explains that even though psychedelic music is not normally associated with the Beach Boys, the "odd directions" and experiments in Pet Sounds "put it all on the map. ... basically that sort of opened the door—not for groups to be formed or to start to make music, but certainly to become as visible as say Jefferson Airplane or somebody like that."[265][nb 35] Decider wrote that the album "almost single-handedly created the idea of 'baroque pop'."[266] Many Los Angeles record producers imitated the album's orchestral style, which became a component to the sunshine pop acts that followed.[267] Discussing smooth soul, Chicago Reader's Noah Berlatsky argued that the Beach Boys helped bridge a gap between the polished pop harmonizing of the Drifters and the experimentation of the Chi-Lites, particularly with "Sloop John B", whose "fussy" arrangements, "pure" harmonies, and "childish vulnerability" he says "come out of a tradition of pop R&B".[268]

—Joel Freimark, January 2016[269]

Along with Rubber Soul, Revolver, and the 1960s folk movement, Greene credited Pet Sounds with spawning the majority of trends in post-1965 rock music.[254] Many British groups responded to the album by making more experimental use of recording studio techniques.[196][nb 36] Composer and journalist Frank Oteri called the album a "clear precedent" to the birth of album-oriented rock and progressive rock.[271] Author Bill Martin felt that the album represented a turning point for progressive rock as the Beach Boys and the Beatles transformed rock music from dance music into music that was made for listening to, bringing "expansions in harmony, instrumentation (and therefore timbre), duration, rhythm, and the use of recording technology".[272]

Pet Sounds is viewed by David Leaf as a herald of the art rock genre,[92] while Jones specifically locates it to the genre's beginning.[91][nb 37] Sommer writes that "Pet Sounds proved that a pop group could make an album-length piece comparable with the greatest long-form works of Bernstein, Copland, Ives, and Rodgers and Hammerstein."[105] Bill Holdship said that it was "perhaps rock's first example of self-conscious art".[276] According to Jim Fusilli, author of the 33⅓ book on the album, it raised itself to "the level of art through its musical sophistication and the precision of its statement",[277] while academic Michael Johnson said that the album was one of the first documented moments of ascension in rock music.[278] Conversely, Gene Sculatti recognized the Beatles' Rubber Soul as having originated the concept of "rock as art" which Pet Sounds elaborated on.[215][nb 38]

Wilson became a "godfather" to an era of indie musicians who were inspired by his melodic sensibilities, studio experimentation, and chamber pop orchestrations.[280] Chamber pop itself was based on the template provided by Pet Sounds,[281] The album's influence on early 2000s emo music, according to writer Sean Cureton, is evident on Weezer's Pinkerton (1996) and Death Cab for Cutie's Transatlanticism (2003).[282] Treblezine's Ernest Simpson and Wild Nothing's Jack Tatum additionally characterize Pet Sounds as the first emo album.[264][283]

Hip-hop producer Questlove recalled that for "black teenagers coming of age in the 1980s", the Beach Boys were out of fashion, and that in the late 1990s, he was ridiculed by "J Dilla, Common, Proof, and a whole bunch of east-side Detroit cats" for enjoying Pet Sounds. Later, "Dilla was like, 'Yeah, you're right man, they had some shit on there.'"[284]

Cultural references

Pet Sounds has inspired tribute albums such as Do It Again: A Tribute to Pet Sounds (2005), The String Quartet Tribute to the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds (2006), MOJO Presents Pet Sounds Revisited (2012), and A Tribute to Pet Sounds (2016).[285] Pet Sounds in the Key of Dee (2007) is a mashup of the album with J-Dilla, by record producer Bullion.[286]

In the mid-1990s, Robert Schneider of the Apples in Stereo and Jim McIntyre of Von Hemmling founded Pet Sounds Studio, which served as the venue for many Elephant 6 projects such as Neutral Milk Hotel's In the Aeroplane Over the Sea,[287] and the Olivia Tremor Control's Dusk at Cubist Castle[288] and Black Foliage.[287]

The album motivated film producer Bill Pohlad to direct the 2014 biopic on Brian Wilson, Love & Mercy, which includes a substantial depiction of the album's making, with actor Paul Dano playing Brian.[289]

Live performances

.jpg)

After its release, several selections from Pet Sounds became staples for the group's live performances, including "Wouldn't It Be Nice", "Sloop John B" and "God Only Knows". Other songs were performed, albeit sporadically and infrequently through the years, and the album was never performed in its entirety with every original group member.[290] In the late 1990s, Carl Wilson vetoed an offer for the Beach Boys to perform Pet Sounds in full for ten shows, reasoning that the studio arrangements were too complex for the stage, and that Brian could not possibly sing his original parts.[291]

As a solo artist, Brian performed the entire album live in 2000 with a different orchestra in each venue, and on three occasions without orchestra on his 2002 tour.[292] Recordings from Wilson's 2002 concert tour were released as Brian Wilson Presents Pet Sounds Live.[293] Rolling Stone's Dorian Lynskey says that the shows helped establish the now-ubiquitous practice of artists playing "classic albums" in their entirety.[294] In 2013, he performed the album at two shows, unannounced, also with Jardine as well as original Beach Boys guitarist David Marks.[295][296] In 2016, Wilson performed the album at several events in Australia, Japan, Europe, Canada and the United States. The tour was planned as his final performances of the album,[297] but occasional shows have been performed or announced through 2020.

Release history

Pet Sounds has had many different reissues since its release in 1966, including remastered mono and stereo versions. Its first reissue was in 1972, packaged as a bonus LP with the Beach Boys' latest album Carl and the Passions – "So Tough".[298] The first release of the album on CD came in 1990, when it was released with the addition of three previously unreleased bonus tracks: "Unreleased Backgrounds" (an a cappella demo section of "Don't Talk" sung by Wilson), "Hang On to Your Ego", and "Trombone Dixie".[299] This 1990 reissue was one of the first CDs to sell more than a million copies.[300]

In 1997, The Pet Sounds Sessions box set was released. It included the original mono release of Pet Sounds, the first stereo release (created by Mark Linett), and three discs of unreleased material.[301] In 2001, Pet Sounds was re-released with the mono and improved stereo versions, plus "Hang On to Your Ego" as a bonus track, all on one disc.[301][302] On August 29, 2006, Capitol released a 40th Anniversary edition, containing a new 2006 remaster of the original mono mix, DVD mixes (stereo and Surround Sound), and a "making of" documentary.[243] The discs were released in a regular jewel box and a deluxe edition was released in a green fuzzy box. A two-disc colored gatefold vinyl set was released with green (stereo) and yellow (mono) discs.[243] In 2016, a 50th anniversary edition box set presents the remastered album in both stereo and mono forms alongside studio sessions outtakes, alternate mixes, and live recordings. Of the 104 tracks, only 14 were previously unreleased.[303]

Track listing

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Wouldn't It Be Nice" |

| Brian Wilson and Mike Love | 2:25 |

| 2. | "You Still Believe in Me" |

| B. Wilson | 2:31 |

| 3. | "That's Not Me" |

| Love with B. Wilson | 2:28 |

| 4. | "Don't Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder)" |

| B. Wilson | 2:53 |

| 5. | "I'm Waiting for the Day" |

| B. Wilson | 3:05 |

| 6. | "Let's Go Away for Awhile" | Wilson | instrumental | 2:18 |

| 7. | "Sloop John B" | traditional, arranged by Wilson | B. Wilson and Love | 2:58 |

| Total length: | 18:38 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "God Only Knows" |

| Carl Wilson with B. Wilson and Bruce Johnston | 2:51 |

| 2. | "I Know There's an Answer" |

| Love and Al Jardine with B. Wilson | 3:09 |

| 3. | "Here Today" |

| Love | 2:54 |

| 4. | "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times" |

| B. Wilson | 3:12 |

| 5. | "Pet Sounds" | Wilson | instrumental | 2:22 |

| 6. | "Caroline, No" |

| B. Wilson | 2:51 |

| Total length: | 17:19 | |||

Vocals according to Alan Boyd and Craig Slowinski.[108] Mike Love's writing credits for "Wouldn't It Be Nice" and "I Know There's an Answer" were only awarded after a 1994 court case.[31] Al Jardine's contribution to the arrangement of "Sloop John B" remains uncredited.[304]

Personnel

Per band archivist Craig Slowinski.[108]

The Beach Boys

- Al Jardine – vocals

- Bruce Johnston – vocals

- Mike Love – vocals

- Brian Wilson – vocals; producer; plucked piano strings on "You Still Believe in Me"; bass guitar, Danelectro bass, and organ on "That's Not Me"; piano on "Pet Sounds"; overdubbed organ or harmonium on "I Know There's an Answer"

- Carl Wilson – vocals; lead guitar and overdubbed 12-string electric guitar on "That's Not Me"; 12-string electric guitar on "God Only Knows"

- Dennis Wilson – vocals; drums on "That's Not Me"

Guests

- Tony Asher – plucked piano strings on "You Still Believe in Me"

- Steve Korthof – tambourine on "That's Not Me"

- Terry Melcher – tambourine on "That's Not Me" and "God Only Knows"

- Marilyn Wilson – additional vocals on "You Still Believe in Me" introduction (uncertain)

- Tony (surname unknown) – tambourine on "Sloop John B"

Session musicians (also known as "the Wrecking Crew")

- Chuck Berghofer – string bass

- Hal Blaine – bicycle horn, drums, percussion, sleigh bells, timpani

- Glen Campbell – banjo, guitar

- Frank Capp – bells, beverage cup, timpani, glockenspiel, tambourine, temple blocks, vibraphone

- Al Casey – guitar

- Roy Caton – trumpet

- Jerry Cole – electric guitar, guitar

- Gary Coleman – bongos, timpani

- Mike Deasy – guitar

- Al De Lory – harpsichord, organ, piano, tack piano

- Steve Douglas – alto saxophone, clarinet, flute, piano, temple blocks, tenor saxophone

- Carl Fortina – accordion

- Ritchie Frost – drums, bongos, Coca-Cola cans

- Jim Gordon – drums, orange juice cups

- Bill Green – alto saxophone, clarinet, flute, güiro, tambourine

- Leonard Hartman – bass clarinet, clarinet, English horn

- Jim Horn – alto saxophone, clarinet, baritone saxophone, flute

- Paul Horn – flute

- Jules Jacob – flute

- Plas Johnson – clarinet, güiro, flute, piccolo, tambourine, tenor saxophone

- Carol Kaye – electric bass, guitar

- Barney Kessel – guitar

- Bobby Klein – clarinet

- Larry Knechtel – harpsichord, organ, tack piano

- Frank Marocco – accordion

- Gail Martin – bass trombone

- Nick Martinis – drums

- Mike Melvoin – harpsichord

- Jay Migliori – baritone saxophone, bass clarinet, bass saxophone, clarinet, flute

- Tommy Morgan – bass harmonica

- Jack Nimitz – baritone saxophone, bass saxophone

- Bill Pitman – guitar

- Ray Pohlman – electric bass

- Don Randi – tack piano

- Alan Robinson – french horn

- Lyle Ritz – string bass, ukulele

- Billy Strange – electric guitar, guitar, 12-string electric guitar

- Ernie Tack – bass trombone

- Paul Tanner – Electro-Theremin

- Tommy Tedesco – acoustic guitar

- Jerry Williams – timpani

- Julius Wechter – bicycle bell, tambourine, timpani, vibraphone

The Sid Sharp Strings

- Arnold Belnick – violin

- Norman Botnick – viola

- Joseph DiFiore – viola

- Justin DiTullio – cello

- Jesse Erlich – cello

- James Getzoff – violin

- Harry Hyams – viola

- William Kurasch – violin

- Leonard Malarsky – violin

- Jerome Reisler – violin

- Joseph Saxon – cello

- Ralph Schaeffer – violin

- Sid Sharp – violin

- Darrel Terwilliger – viola

- Tibor Zelig – violin

Engineers

- Bruce Botnick

- Chuck Britz

- H. Bowen David

- Larry Levine

- Other engineers may have included Jerry Hochman, Phil Kaye, Jim Lockert, and Ralph Valentine.

Charts

Weekly charts

| Year | Chart | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1966 | US Billboard Top LPs[305] | 10 |

| 1966 | UK Albums Chart[306] | 2 |

| 1972 | US Billboard Top LPs & Tape[305] | 50 |

| 1990 | US Billboard 200 Albums[305] | 162 |

| 1995 | UK Albums Chart[306] | 17 |

Singles

| Charts (1966) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Singles Chart | 17 |

| Austria (Ö3 Austria Top 40)[307] | 1 |

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Flanders)[308] | 5 |

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Wallonia)[309] | 39 |

| Canada RPM Singles Chart | 2 |

| Germany (Official German Charts)[310] | 1 |

| Ireland (IRMA)[311] | 2 |

| Netherlands (Single Top 100)[312] | 1 |

| Norway (VG-lista)[313] | 1 |

| UK Singles Chart[314] | 2 |