Ukulele

The ʻukulele (/ˌjuːkəˈleɪli/ YOO-kə-LAY-lee; from Hawaiian: ʻukulele [ˈʔukuˈlɛlɛ], approximately OO-koo-LEH-leh) or ukelele[1] is a member of the lute family of instruments. It generally employs four nylon strings.[2][3]

Martin 3K ʻUkulele | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | String instrument (plucked, nylon stringed instrument usually played with the bare thumb and/or fingertips, or a felt pick) |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322 (Composite chordophone) |

| Developed | 19th century |

| Related instruments | |

| |

The ʻukulele originated in the 19th century as a Hawaiian adaptation of the Portuguese machete,[4] a small guitar-like instrument, which was introduced to Hawaii by Portuguese immigrants, mainly from Madeira and the Azores. It gained great popularity elsewhere in the United States during the early 20th century and from there spread internationally.

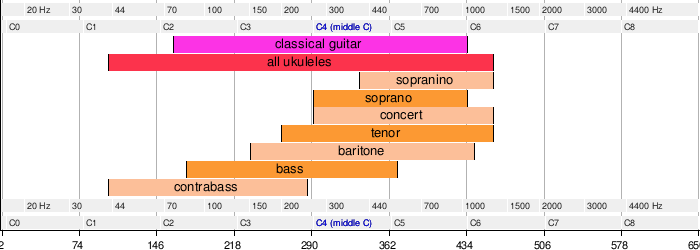

The tone and volume of the instrument vary with size and construction. Ukuleles commonly come in four sizes: soprano, concert, tenor, and baritone.

History

The ʻukulele is commonly associated with music from Hawaii where the name roughly translates as "jumping flea",[5] perhaps because of the movement of the player's fingers. Legend attributes it to the nickname of the Englishman Edward William Purvis, one of King Kalākaua's officers, because of his small size, fidgety manner, and playing expertise. One of the earliest appearances of the word ʻukulele in print (in the sense of a stringed instrument) is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Catalogue of the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments of All Nations published in 1907. The catalog describes two ukuleles from Hawaii: one that is similar in size to a modern soprano ʻukulele, and one that is similar to a tenor (see § Types and sizes).[6]

Developed in the 1880s, the ʻukulele is based on several small guitar-like instruments of Portuguese origin, the machete,[4] the cavaquinho, the timple, and the rajão, introduced to the Hawaiian Islands by Portuguese immigrants from Madeira and Cape Verde.[7] Three immigrants in particular, Madeiran cabinet makers Manuel Nunes, José do Espírito Santo, and Augusto Dias, are generally credited as the first ukulele makers.[8] Two weeks after they disembarked from the SS Ravenscrag in late August 1879, the Hawaiian Gazette reported that "Madeira Islanders recently arrived here, have been delighting the people with nightly street concerts."[9]

One of the most important factors in establishing the ukulele in Hawaiian music and culture was the ardent support and promotion of the instrument by King Kalākaua. A patron of the arts, he incorporated it into performances at royal gatherings.[10]

Kamaka Ukulele or just Kamaka is a family-owned Hawaii-based maker of the ʻukulele, founded in 1916, that is often credited with producing some of the world's finest, and created the first pineapple ʻukulele.

Canada

In the 1960s, educator J. Chalmers Doane dramatically changed school music programs across Canada, using the ʻukulele as an inexpensive and practical teaching instrument to foster musical literacy in the classroom.[11] 50,000 schoolchildren and adults learned ʻukulele through the Doane program at its peak.[12] Today, a revised program created by James Hill and J. Chalmers Doane is still a staple of music education in Canada.

Japan

The ʻukulele arrived in Japan in 1929 after Hawaiian-born Yukihiko Haida returned to the country upon his father's death and introduced the instrument. Haida and his brother Katsuhiko formed the Moana Glee Club, enjoying rapid success in an environment of growing enthusiasm for Western popular music, particularly Hawaiian and jazz. During World War II, authorities banned most Western music, but fans and players kept it alive in secret, and it resumed popularity after the war. In 1959, Haida founded the Nihon Ukulele Association. Today, Japan is considered a second home for Hawaiian musicians and ʻukulele virtuosos.[13]

United Kingdom

British singer and comedian George Formby was a ʻukulele player, though he often played a banjolele, a hybrid instrument consisting of an extended ukulele neck with a banjo resonator body. Demand surged in the new century because of its relative simplicity and portability.[14] Another British ukulele player was Tony Award winner Tessie O'Shea, who appeared in numerous movies and stage shows, and was twice on The Ed Sullivan Show, including the night The Beatles debuted in 1964.[15] The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain tours globally, and the George Formby Society, established in 1961, continues to hold regular conventions.

United States mainland

Pre-World War II

The ʻukulele was popularized for a stateside audience during the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, held from spring to fall of 1915 in San Francisco.[16] The Hawaiian Pavilion featured a guitar and ʻukulele ensemble, George E. K. Awai and his Royal Hawaiian Quartet,[17] along with ʻukulele maker and player Jonah Kumalae.[18] The popularity of the ensemble with visitors launched a fad for Hawaiian-themed songs among Tin Pan Alley songwriters.[19] The ensemble also introduced both the lap steel guitar and the ukulele into U.S. mainland popular music,[20] where it was taken up by vaudeville performers such as Roy Smeck and Cliff "Ukulele Ike" Edwards. On April 15, 1923 at the Rivoli Theater in New York City, Smeck appeared, playing the ukulele, in Stringed Harmony, a short film made in the DeForest Phonofilm sound-on-film process. On August 6, 1926, Smeck appeared playing the ʻukulele in a short film His Pastimes, made in the Vitaphone sound-on-disc process, shown with the feature film Don Juan starring John Barrymore.[21]

The ʻukulele soon became an icon of the Jazz Age.[22] Like guitar, basic ʻukulele skills can be learned fairly easily, and this highly portable, relatively inexpensive instrument was popular with amateur players throughout the 1920s, as evidenced by the introduction of uke chord tablature into the published sheet music for popular songs of the time,[22] (a role that would be supplanted by the guitar in the early years of rock and roll).[23] A number of mainland-based stringed-instrument manufacturers, among them Regal, Harmony, and especially Martin added ukulele, banjolele, and tiple lines to their production to take advantage of the demand.

The ʻukulele also made inroads into early country music or old-time music[24] parallel to the then popular mandolin. It was played by Jimmie Rodgers and Ernest V. Stoneman, as well as by early string bands, including Cowan Powers and his Family Band, Da Costa Woltz's Southern Broadcasters, Walter Smith and Friends, The Blankenship Family, The Hillbillies, and The Hilltop Singers.[24]

Post-World War II

From the late 1940s to the late 1960s, plastics manufacturer Mario Maccaferri turned out about 9 million inexpensive ʻukuleles.[25] The ukulele remained popular, appearing on many jazz songs throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.[26] Much of the instrument's popularity (particularly the baritone size) was cultivated via The Arthur Godfrey Show on television.[27] Singer-musician Tiny Tim became closely associated with the instrument after playing it on his 1968 hit "Tiptoe Through the Tulips".

Post-1990 revival

After the 1960s, the ʻukulele declined in popularity until the late 1990s, when interest in the instrument reappeared.[28] During the 1990s, new manufacturers began producing ʻukuleles and a new generation of musicians took up the instrument. Jim Beloff set out to promote the instrument in the early 1990s and created over two dozen ʻukulele music books featuring modern music as well as classic ukulele pieces.[29]

All-time best selling Hawaiian musician Israel Kamakawiwo'ole helped re-popularise the instrument, in particular with his 1993 reggae-rhythmed medley of "Over the Rainbow" and "What a Wonderful World," used in films, television programs, and commercials. The song reached no. 12 on Billboard's Hot Digital Tracks chart the week of January 31, 2004.[30]

The creation of YouTube was a large influence on the popularity of the ʻukulele. One of the first videos to go viral was Jake Shimabukuro's ʻukulele rendition of George Harrison's "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" on YouTube. The video quickly went viral, and as of April 2019, had received over 16 million views.[31]

Construction

The ʻukulele is generally made of wood, though variants have been composed partially or entirely of plastic or other materials. Cheaper ʻukuleles are generally made from plywood or laminate woods, in some cases with a soundboard of a tonewood such as spruce. More expensive ʻukuleles are made of solid hardwoods such as mahogany. The traditionally preferred wood for ukuleles is a type of acacia endemic to Hawaiʻi, called koa.

Typically, ʻukuleles have a figure-eight body shape similar to that of a small acoustic guitar. They are also often seen in non-standard shapes, such as cutaway shape and an oval, usually called a "pineapple" ʻukulele, invented by the Kamaka Ukulele company, or a boat-paddle shape, and occasionally a square shape, often made out of an old wooden cigar box.

These instruments usually have four strings; some strings may be paired in courses, giving the instrument a total of six or eight strings (primarily for greater strumming volume.) The strings themselves were originally made of catgut. Modern ʻukuleles use nylon polymer strings, with many variations in the material, such as fluorocarbon, aluminium (as winding on lower-pitched strings),[32] and Nylgut.[33]

Instruments with 6 or 8 strings in four courses are often called taropatches, or taropatch ʻukuleles. They were once common in a concert size, but now the tenor size is more common for six-string taropatch ʻukuleles. The six string, four course version, has two single and two double courses, and is sometimes called a Lili'u, though this name also applies to the eight-string version.[34] Eight-string baritone taropatches exist,[35] and, 5-string tenors have also been made.[36] A Javanese ʻukulele commonly has only three strings. Apparently, it's a modern innovation, as the first generation of three-stringed ʻukuleles were four stringed instruments with one string removed. They are now manufactured with only three strings.

Types and sizes

Common types of ʻukuleles include soprano (standard ʻukulele), concert, tenor, and baritone. Less common are the sopranino (also called piccolo, bambino, or "pocket uke"), bass, and contrabass ʻukuleles.[37] The soprano, often called "standard" in Hawaii, is the second-smallest and was the original size. The concert size was developed in the 1920s as an enhanced soprano, slightly larger and louder with a deeper tone. Shortly thereafter, the tenor was created, having more volume and deeper bass tone. The baritone (resembling a smaller tenor guitar) was created in the 1940s, and the contrabass and bass are recent innovations (2010 and 2014, respectively).[38][39]

Size and popular tunings of standard ʻukulele types:

| Type | Alternate names |

Typical length |

Scale length[40] |

Frets | Range[41] | Common tuning[42] |

Alternate tunings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| piccolo, sopranino, sopranissimo | 16 in (41 cm) | 11 in (28 cm) | 10–12 | G4–D6 (E6) | D5 G4 B4 E5 | C5 F4 A4 D5 | |

| Soprano | standard, ukulele | 21 in (53 cm) | 13 in (33 cm) | 12–15 | C4–A5 (C6) | G4 C4 E4 A4[43] | A4 D4 F♯4 B4 G3 C4 E4 A4[43] |

| Concert | alto | 23 in (58 cm) | 15 in (38 cm) | 15–18 | C4–C6 (D♯ 6) | G4 C4 E4 A4[43] | G3 C4 E4 A4[43] |

| Tenor | taro patch, Liliʻu[44] | 26 in (66 cm) | 17 in (43 cm) | 17–19 | G3–D6 (E6) | G4 C4 E4 A4 ("High G") G3 C4 E4 A4 ("Low G") |

D4 G3 B3 E4[43] A3 D4 F♯4 B4 |

| Baritone | bari, bari uke, taropatch[45] |

29 in (74 cm) | 19 in (48 cm) | 18–21 | D3–A♯5 (C♯ 6) | D3 G3 B3 E4 | C3 G3 B3 E4 |

| Bass[46] | 30 in (76 cm) | 20 in (51 cm) | 16–18 | E2–B4 (C♯ 5) | E2 A2 D3 G3 | ||

| Contrabass | U-Bass, Rumbler[47] | 32 in (81 cm) | 21 in (53 cm) | 16 | E1–B3 | E1 A1 D2 G2 | D1 A1 D2 G2 ("Drop D") |

Range of notes of standard ukulele types:

Note that range varies with the tuning and size of the instruments. The examples shown in the chart reflect the range of each instrument from the lowest standard tuning, to the highest fret in the highest standard tuning.

Tuning

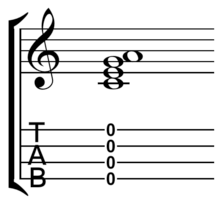

One of the most common tunings for the standard or soprano ʻukulele is C6 tuning: G4–C4–E4–A4, which is often remembered by the notes in the "My dog has fleas" jingle (see sidebar).[48] The G string is tuned an octave higher than might be expected, so this is often called "high G" tuning. This is known as a "reentrant tuning"; it enables uniquely close-harmony chording.

More rarely used with the soprano ʻukulele is C6 linear tuning, or "low G" tuning, which has the G in sequence an octave lower: G3–C4–E4–A4, which is equivalent to playing the top four strings (DGBE) of a guitar with a capo on the fifth fret.

Another common tuning for the soprano ʻukulele is the higher string-tension D6 tuning (or simply D tuning), A4–D4–F♯4–B4, one step higher than the G4–C4–E4–A4 tuning. Once considered standard, this tuning was commonly used during the Hawaiian music boom of the early 20th century, and is often seen in sheet music from this period, as well as in many method books through the 1980s. D6 tuning is said by some to bring out a sweeter tone in some ukuleles, generally smaller ones. D6 tuning with a low fourth string, A3–D4–F♯4–B4, is sometimes called "Canadian tuning" after its use in the Canadian school system, mostly on concert or tenor ʻukuleles, and extensive use by James Hill and J. Chalmers Doane.[49]

Whether C6 or D6 tuning should be the "standard" tuning is a matter of long and ongoing debate. There are historic and popular ukulele methods that have used each.[50]

For the concert and tenor ʻukuleles, both reentrant and linear C6 tunings are standard; linear tuning in particular is widely used for the tenor ʻukulele, more so than for the soprano and concert instruments.

The baritone ʻukulele usually uses linear G6 tuning: D3–G3–B3–E4, the same as the highest four strings of a standard 6-string guitar.

Bass ʻukuleles are tuned similarly to bass guitars: E1–A1–D2–G2 for U-Bass style instruments (sometimes called contrabass), or an octave higher, E2–A2–D3–G3, for Ohana type metal-string basses.

Sopranino ʻukulele tuning is less standardized. They usually are tuned re-entrantly, but frequently at a higher pitch than C; for example, re-entrant G6 tuning: D5–G4–B4–E5.

As is commonly the case with string instruments, other tunings may be preferred by individual players. For example, special string sets are available to tune the baritone ʻukulele in linear C6. Some players tune ʻukuleles like other four-string instruments such as the mandolin,[51] Venezuelan cuatro,[52] or dotara.[53] Ukuleles may also be tuned to open tunings, similar to the Hawaiian slack key style.[54]

Related instruments

ʻUkulele varieties include hybrid instruments such as the guitalele (also called guitarlele), banjo ʻukulele (also called banjolele), harp ʻukulele, lap steel ʻukulele, and the ukelin. It is very common to find ʻukuleles mixed with other stringed instruments because of the amount of strings and the easy playing ability. There is also an electrically amplified variant of the ʻukulele. The resonator ʻukulele produces sound by one or more spun aluminum cones (resonators) instead of the wooden soundboard, giving it a distinct and louder tone. The Tahitian ʻukulele, another variant, is usually carved from a single piece of wood,[55] and does not have a hollow soundbox.

Close cousins of the ʻukulele include the Portuguese forerunners, the cavaquinho (also commonly known as machete or braguinha) and the slightly larger rajão. Other relatives include, the Venezuelan cuatro, the Colombian tiple, the timple of the Canary Islands, the Spanish vihuela, the Mexican requinto jarocho, and the Andean charango traditionally made of an armadillo shell. In Indonesia, a similar Portuguese-inspired instrument is the kroncong.[56]

Audio samples

See also

- List of ukulele musicians

- Stringed instrument tunings

References

- "ukulele". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Erich M. von Hornbostel & Curt Sachs, "Classification of Musical Instruments: Translated from the Original German by Anthony Baines and Klaus P. Wachsmann." The Galpin Society Journal 14, 1961: 3–29.

- "Ukulele". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Tranquada and King (2012). The Ukulele, A History. Hawaii University Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3634-4.

- Beloff 2003, p. 13

- Catalogue of the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments of All Nations. Volume III. Instruments of Savage Tribes and Semi-Civilized Peoples, Part 2. Oceania. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1907. p. 51.

- Nidel, Richard (2004). World Music: The Basics. Routledge. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-415-96800-3.

- Roberts, Helen (1926). Ancient Hawaiian Music. Bernice P. Bishop Museum. pp. 9–10.

- King, John (2003). "Prolegomena to a History of the 'Ukulele". Ukulele Guild of Hawai'i.

- "David Kalakaua (1836–1891), Inaugural Hall of Fame Inductee, 1997". Ukulele Hall of Fame Museum. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- Karr, Gary, and McMillan, Barclay (1992). "J. Chalmers Doane". Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Beloff 2003, p. 111

- Beloff, Jim (2003). The Ukulele: A Visual History. Backbeat books. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-87930-758-5.

- Fladmark, Judy (2010-02-19). "Ukulele sends UK crazy". BBC News.

- Tranquada, Jim (2012). The Ukulele: a History. University of Hawaii Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8248-3544-6.

- Lipsky, William (2005). San Francisco's Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Arcadia Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7385-3009-3.

- Doyle, Peter (2005). Echo and Reverb: Fabricating Space in Popular Music Recording, 1900–1960. Wesleyan. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8195-6794-9.

- "Jonah Kumalae (1875–1940), 2002 Hall of Fame Inductee". Ukulele Hall of Fame Museum. 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- Koskoff, Ellen (2005). Music Cultures in the United States: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-415-96588-0.

- Volk, Andy (2003). Lap Steel Guitar. Centerstream Publications. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-57424-134-1.

- Whitcomb, Ian (2000). Ukulele Heaven: Songs from the Golden Age of the Ukulele. Mel Bay Publications. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7866-4951-8.

- Whitcomb, Ian (2001). Uke Ballads: A Treasury of Twenty-five Love Songs Old and New. Mel Bay Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7866-1360-1.

- Sanjek, Russell (1988). American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years. Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-19-504311-1.

- Rev, Lil'. ""Just a few penny dreadfuls": the Ukulele and Old-Time Country Music". www.oldtimeherald.org. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- Wright, Michael. "Maccaferri History: The Guitars of Mario Maccaferri". Vintage Guitar. Archived from the original on 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- "The Ukulele". Peterborough Music. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-15.The Ukulele

- "Arthur Godfrey (1903–1983), 2001 Hall of Fame Inductee". Ukulele Hall of Fame Museum. 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- John Shepherd (27 February 2003). Continuum encyclopedia of popular music of the world: VolumeII: Performance and production. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 450–. ISBN 978-0-8264-6322-7. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Mighty Uke, Interview with Jim Beloff, 2010

- Billboard, for the survey week ending January 18, 2004.

- cromulantman (22 April 2006). "Ukulele weeps by Jake Shimabukuro". Retrieved 3 April 2019 – via YouTube.

- "Ukulele Strings - C.F. Martin & Co". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Aquila Nylgut Ukulele Strings, wholesale source for retailers and dealers". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "110mb.com - Want to start a website?". Archived from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Kamaka Baritone 8 String HF-48". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Kala -KA-ATP-CTG Solid Cedar Top Tenor Slothead -Gloss Finish". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Lamorinda Music". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "The story behind the wildly popular Kala U-Bass". 7 January 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Uke Baritone Bass w/Preamp Tattoo - Luna Guitars". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- The “scale” is the length of the playable part of the strings, from the nut at the top to the bridge at the bottom.

- Exact range depends on the tuning and the number of frets.

- On the soprano, concert, and tenor instruments, the most common tuning results in a "bottom" string that is not the lowest in pitch, as it is tuned a 5th higher than the next string (and a major 2nd below the "top" string). This is called re-entrant tuning.

- "Ukulele/Banjouke". 2 January 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Tenor ukuleles exist in a variety of styles, with 4, 5, 6, and 8 strings. What the tenor is called depends on which style it has been designed in.

- Eight-string "taropatch" baritone ukuleles have been made; however, they are very rare. See, for example, the Kamaka HF-48

- See the Luna Uke Bass and the Kala U-Bass

- U-Bass and Rumbler are trade names of the Kala ukulele company

- "Ukulele in the Classroom". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "James Hill - FAQ". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Tranquada, J.; The Ukulele: A History; University of Hawaii Press; Honolulu: 2012. 0824-83634-0 According to Tranquanda, ""This is an old and seemingly never-ending argument. While the pioneering methods of Kaai (1906) and Rollinson (1909) both use C tuning, a sampling of the methods that follow give a sense of the unresolved nature of the debate: Kealakai (1914), D tuning; Bailey (1914), C tuning; Kia (1914), D tuning; Kamiki (1916), D tuning; Guckert (1917), C tuning; Stumpf (1917), D tuning."

- Russell, Robert (15 September 2017). "How to Play a Ukulele Like a Mandolin". Our Pastimes. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Middleton, Ken (2 May 2018). "Cuatro Tuning On a Ukulele". Retrieved 19 November 2019 – via YouTube.

- Ovi, Rahatul Islam (24 April 2017). "Ukulele Dotara Style Tuning - ইউকালেলি দোতারা স্টাইল টিউনিং". Rahatul & Dukulele. Retrieved 24 April 2017 – via YouTube.

- Kimura, Heeday. How to Play Slack Key Ukulule.

- University of the South Pacific. Institute of Pacific Studies (2003). Cook Islands culture. Institute of Pacific Studies in Association with the Cook Islands Extension Centre, University of the South Pacific, the Cook Islands Cultural and Historic Places Trust, and the Ministry of Cultural Development. ISBN 978-982-02-0348-8. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Jeremy Wallach (22 October 2008). Modern Noise, Fluid Genres: Popular Music in Indonesia, 1997–2001. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-0-299-22904-7. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ukulele. |

- "Bass Ukulele utilizing Ashbory strings". largesound.com.

- "The Ukulele & You". Museum of Making Music. Carlsbad, CA. An exhibition that details the ukulele's history and waves of mainstream popularity.

- "Ukulele Brand name database". Tiki King. Information about over 600 ukulele makers past and present.