Panic of 1837

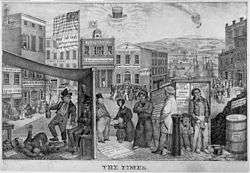

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression that lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down while unemployment went up. Pessimism abounded during the time. The panic had both domestic and foreign origins. Speculative lending practices in western states, a sharp decline in cotton prices, a collapsing land bubble, international specie flows, and restrictive lending policies in Great Britain were all to blame.[1][2] On May 10, 1837, banks in New York City suspended specie payments, meaning that they would no longer redeem commercial paper in specie at full face value.[3] Despite a brief recovery in 1838, the recession persisted for approximately seven years. Banks collapsed, businesses failed, prices declined, and thousands of workers lost their jobs. Unemployment may have been as high as 25% in some locales. The years 1837 to 1844 were, generally speaking, years of deflation in wages and prices.[4]

Causes

The crisis followed a period of economic expansion from mid-1834 to mid-1836. The prices of land, cotton, and slaves rose sharply in these years. The origins of this boom had many sources, both domestic and international. Because of the peculiar factors (Specie Circular) of international trade at the time, abundant amounts of silver were coming into the United States from Mexico and China. Land sales and tariffs on imports were also generating substantial federal revenues. Through lucrative cotton exports and the marketing of state-backed bonds in British money markets, the United States acquired significant capital investment from Great Britain. These bonds financed transportation projects in the United States. British loans, made available through Anglo-American banking houses like Baring Brothers, fueled much of the United States's westward expansion, infrastructure improvements, industrial expansion, and economic development during the antebellum era.[5]

From 1834 to 1835 Europe experienced extreme prosperity, resulting in confidence and an increased propensity for taking risks in foreign investment. In 1836, directors of the Bank of England noticed that the Bank's monetary reserves had declined precipitously in recent years due to the increase in capital speculation and investment in American transportation. Conversely, improved transportation systems increased the supply of cotton, dropping the price it could fetch at market. Cotton prices were security for loans, and America's cotton kings defaulted. Furthermore, in 1836 and 1837 American wheat crops suffered from Hessian Fly and winter kill, so the price of wheat in America increased greatly, causing American labor to starve.[6]

This hunger in America was not felt by England, as her wheat crops improved every year from 1831 to 1836, and European imports of American wheat had dropped to "almost nothing" by 1836. [7]The directors of the Bank of England, wanting to increase monetary reserves (And cushion American defaults) indicated that they would gradually raise interest rates from 3 to 5 percent. The conventional financial theory held that banks should raise interest rates and curb lending when faced with low monetary reserves. Raising interest rates, according to the laws of supply and demand, was supposed to attract species since money generally flows where it will generate the greatest return (assuming equal risk among possible investments). In the open economy of the 1830s, characterized by free trade and relatively weak trade barriers, the monetary policies of the hegemonic power – in this case, Great Britain – were transmitted to the rest of the interconnected global economic system, including the U.S. The result was that as the Bank of England raised interest rates, major banks in the United States were forced to do the same.[8]

When New York banks raised interest rates and scaled back on lending, the effects were damaging. Since the price of a bond bears an inverse relationship to the yield (or interest rate), the increase in prevailing interest rates would have forced down the price of American securities. Importantly, demand for cotton plummeted. The price of cotton fell by 25% in February and March 1837.[9] The United States economy, especially in the southern states, was heavily dependent on stable cotton prices. Receipts from cotton sales provided funding for some schools, balanced the nation's trade deficit, fortified the US dollar, and procured foreign exchange earnings in British pound sterling, the world's reserve currency at the time. Since the United States was still a predominantly agricultural economy centered on the export of staple crops and an incipient manufacturing sector,[10] a collapse in cotton prices had massive reverberations.

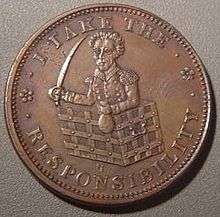

Within the United States, there were several contributing factors. In July 1832, President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill to recharter the Second Bank of the United States (BUS), the nation's central bank and fiscal agent. As the BUS wound up its operations in the next four years, state-chartered banks in the West and South relaxed their lending standards, maintaining unsafe reserve ratios.[2] Two domestic policies exacerbated an already volatile situation. The Specie Circular of 1836 mandated that western lands could be purchased only with gold and silver coin. The circular was an executive order issued by Andrew Jackson and favored by Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and other hard-money advocates. The intent was to curb speculation in public lands, but the circular set off a real estate and commodity price crash as most buyers were unable to come up with sufficient hard money or "specie" (gold or silver coins) to pay for the land. Secondly, the Deposit and Distribution Act of 1836 placed federal revenues in various local banks (derisively termed "pet banks") across the country. Many of these banks were located in western regions. The effect of these two policies was to transfer specie away from the nation's main commercial centers on the East Coast. With lower monetary reserves in their vaults, major banks and financial institutions on the East Coast had to scale back their loans, which was a major cause of the panic along with the real estate crash.[11]

Americans at the time attributed the cause of the panic principally to domestic political conflicts. Democrats typically blamed the bankers. Whigs blamed Jackson for refusing to renew the charter of the Bank, resulting in the withdrawal of government funds from the bank.[12] Martin Van Buren, who became president in March 1837, was largely blamed for the panic even though his inauguration preceded the panic by only five weeks. Van Buren's refusal to use government intervention to address the crisis (such as emergency relief and increasing spending on public infrastructure projects to reduce unemployment) according to his opponents, contributed further to the hardship and duration of the depression that followed the panic. Jacksonian Democrats, on the other hand, blamed the National Bank, both in funding rampant speculation and in introducing inflationary paper money. Some modern economists view Van Buren's deregulatory economic policy as successful in the long term, and argue that it played an important role in revitalizing banks after the panic.[13]

Effects and aftermath

Virtually the whole nation felt the effects of the panic. Connecticut, New Jersey, and Delaware reported the greatest stress in their mercantile districts. In 1837, Vermont's business and credit systems took a hard blow. Vermont had a period of alleviation in 1838, but was hit hard again in 1839–1840. New Hampshire did not feel the effects of the panic as much as its neighbors did. It had no permanent debt in 1838, and did not have a lot of economic stress the following years. New Hampshire's greatest hardship was the circulation of fractional coins inside the state.

Conditions in the South were much worse than the conditions in the East, and the Cotton Belt was dealt the worst blow. In Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina the panic caused an increase in the interest of diversifying crops. New Orleans felt a general depression in business, and its money market stayed in bad condition throughout 1843. Several planters in Mississippi had spent much of their money in advance, leading to the complete bankruptcy of many planters. By 1839, many of the plantations were thrown out of cultivation. Florida and Georgia did not feel the effects as early as Louisiana, Alabama, or Mississippi. In 1837, Georgia had sufficient coin to carry on everyday purchases. Until 1839, citizens of Florida were able to boast about the punctuality of their payments. It was in the 1840s when Georgia and Florida began to feel the negative effects of the panic.

At first the West did not feel as much pressure as the East or the South. Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were agricultural states, and the good crops of 1837 were a relief to the farmers. In 1839, agricultural prices fell and the pressure reached the agriculturalists.[14]

Within two months the losses from bank failures in New York alone aggregated nearly $100 million. Out of 850 banks in the United States, 343 closed entirely, 62 failed partially, and the system of state banks received a shock from which it never fully recovered.[15] The publishing industry was particularly hurt by the ensuing depression.[16]

Many individual states defaulted on their bonds, angering British creditors. For a brief time, the United States withdrew from international money markets. Only in the late 1840s did Americans re-enter these markets. These defaults, along with other consequences of the recession, carried major implications for the relationship between the state and economic development. In some ways, the panic undermined confidence in public support for internal improvements. While state investment in internal improvements remained common in the South until the Civil War, northerners increasingly looked to private investment, rather than public, to finance growth. The panic unleashed a wave of riots and other forms of domestic unrest. The ultimate result was an increase in the state's police powers, including more professional police forces.[17][18]

Recovery

Most economists agree that there was a brief recovery from 1838 to 1839, which then ended as the Bank of England and Dutch creditors raised interest rates.[19] Economic historian Peter Temin has argued that, when corrected for deflation, the economy grew after 1838.[20] According to economist and historian Murray Rothbard, between 1839 and 1843, real consumption increased by 21 percent and real gross national product increased by 16 percent, while real investment fell by 23 percent and the money supply shrank by 34 percent.[21]

In 1842, the American economy was able to rebound somewhat and overcome the five-year depression, but according to most accounts, the economy did not recover until 1843.[22][23] The recovery from the depression intensified after the California gold rush started in 1848, greatly increasing the money supply. By 1850, the U.S. economy was booming again.

Intangible factors like confidence and psychology played powerful roles, helping to explain the magnitude and depth of the panic. Central banks had only limited abilities to control prices and employment at the time, making runs on banks common. When a few banks collapsed, alarm quickly spread throughout the community, heightened by partisan newspapers. Anxious investors rushed to other banks, demanding to have their deposits withdrawn. When faced with such pressure, even healthy banks had to make further curtailments – calling in loans and demanding payment from their borrowers. This fed the hysteria even further, leading to a downward spiral or snowball effect. In other words, anxiety, fear, and a pervasive lack of confidence initiated devastating, self-sustaining feedback loops. Many economists today understand this phenomenon as an information asymmetry. Essentially, bank depositors reacted to imperfect information: they did not know if their deposits were safe, and fearing further risk, they withdrew their deposits, even as this caused more damage. The same concept of downward spiral was true for many southern planters, who speculated in land, cotton, and slaves. Many planters took out loans from banks under the assumption that cotton prices would continue to rise. When cotton prices dropped, however, planters could not pay back their loans, jeopardizing the solvency of many banks. These factors were particularly crucial given the lack of deposit insurance in banks. When bank customers are not assured that their deposits are safe, they are more likely to make rash decisions that can imperil the rest of the economy. Economists today have concluded that suspension of convertibility, deposit insurance, and sufficient capital requirements in banks can limit the possibility of bank runs.[24][25][26]

See also

- State bankruptcies in the 1840s

- Flour riot of 1837

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

References

- Timberlake, Jr., Richard H. (1997). "Panic of 1837". In Glasner, David; Cooley, Thomas F. (eds.). Business cycles and depressions: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 514–16. ISBN 978-0-8240-0944-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Knodell, Jane (September 2006). "Rethinking the Jacksonian Economy: The Impact of the 1832 Bank Veto on Commercial Banking". The Journal of Economic History. 66 (3): 541. doi:10.1017/S0022050706000258.

- Damiano, Sara T. (2016). "The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis by Jessica M. Lepler". Journal of the Early Republic. 36 (2): 420–422. doi:10.1353/jer.2016.0024.

- "Measuring Worth – measures of worth, prices, inflation, purchasing power, etc". Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Jenks, Leland Hamilton (1927). The Migration of British Capital to 1875. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 66–95.

- Davis, Joseph H. (2004). Harvests and Business Cycles in Nineteenth-Century America (PDF). Vanguard Group. p. 14. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Alison, Archibald. History of Europe: From the Fall of Napoleon, in MDCCCXV to the ..., Volume 3. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 265.

- Temin, Peter (1969). The Jacksonian Economy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 122–147.

- Jenks, Leland Hamilton (1927). The Migration of British Capital to 1875. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 87–93.

- North, Douglass C. (1961). The Economic Growth of the United States 1790–1860. Prentice Hall. pp. 1–4.

- Rousseau, Peter L (2002). "Jacksonian Monetary Policy, Specie Flows, and the Panic of 1837". Journal of Economic History. 62 (2): 457–488. doi:10.1017/S0022050702000566.

- Bill White (2014). America's Fiscal Constitution: Its Triumph and Collapse. PublicAffairs. p. 80. ISBN 9781610393430.

- Hummel, Jeffery (1999). "Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President" (PDF). The Independent Review. 4 (n.2): 13–14. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- McGrane, Reginald (1965). The Panic of 1837: Some Financial Problems of the Jacksonian Era. New York: Russell & Russell. pp. 106–126.

- Hubert H. Bancroft, ed. (1902). The financial panic of 1837. The Great Republic By the Master Historians. 3.

- Thompson, Lawrance. Young Longfellow (1807–1843). New York: The Macmillan Company, 1938: 325.

- Larson, John (2001). Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 195–264.

- Roberts, Alasdair (2012). America's First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder after the Panic of 1837. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 49–84, 137–174.

- Friedman, Milton. A Program for Monetary Stability. p. 10.

- Temin, Peter. The Jacksonian Economy. p. 155.

- Rothbard, Murray (18 August 2014). A history of money and banking in the United States: the colonial era to world war II (PDF). p. 102.

- "Six Year Depression 1837–1843". The History Box.

- "Panic of 1837: Van Buren's First Challenge". United States American History.

- Chen, Yehning; Hasan, Iftekhar (2008). "Why Do Bank Runs Look Like Panic? A New Explanation" (PDF). Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 40 (2–3): 537–538. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00126.x.

- Diamond, Douglas W.; Dybvig, Philip H. (1983). "Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity". Journal of Political Economy. 91 (3): 401–419. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.434.6020. doi:10.1086/261155. JSTOR 1837095.

- Goldstein, Itay; Pauzner, Ady (2005). "Demand-Deposit Contracts and the Probability of Bank Runs". Journal of Finance. 60 (3): 1293–1327. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.500.6471. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00762.x.

Further reading

- Balleisen, Edward J. (2001). Navigating Failure: Bankruptcy and Commercial Society in Antebellum America. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 1–49. ISBN 978-0-8078-2600-3.

- Bodenhorn, Howard (2003). State Banking in Early America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514776-6.

- Campbell, Stephen (2017). "The Transatlantic Financial Crisis of 1837," in William Beezley, ed., The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.399

- Curtis, James C. (1970). The Fox at Bay: Martin Van Buren and the Presidency, 1837–1841. Univ. Press of Kentucky. pp. 64–151. ISBN 978-0-8131-1214-5.

- Friedman, Milton (1960). A Program for Monetary Stability. New York: Fordham Univ. Press.

- Goodhart, Charles (1988). The Evolution of Central Banks. MIT Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-262-57073-2.

- Jenks, Leland Hamilton (1927). The Migration of British Capital to 1875. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 66–95.

- Kilbourne, Jr., Richard H. (2006). Slave Agriculture and Financial Markets in Antebellum America: The Bank of the United States in Mississippi, 1831–1852. Pickering and Chatto. pp. 57–105. ISBN 978-1-85196-890-9.

- Kynaston, David (2017). Till Time's Last Sand: A History of the Bank of England, 1694–2013. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-1408868560.

- Lepler, Jessica (May 2012). "The News Flew Like Lightning". Journal of Cultural Economy. 5 (2): 179–195. doi:10.1080/17530350.2012.660784.

- Lepler, Jessica M. The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis (Cambridge University Press; 2013) 337 pages; compares London, New York, and New Orleans between March and May 1837.

- McGrane, Reginald C (1924). The Panic of 1837: Some financial problems of the Jacksonian era.

- Remini, Robert V. (1967). Andrew Jackson and the Bank War. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 126–131. ISBN 978-0-393-09757-3.

- Roberts, Alasdair (2012). America's First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder After the Panic of 1837. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5033-4. online review

- Rousseau, Peter L (2002). "Jacksonian Monetary Policy, Specie Flows, and the Panic of 1837". Journal of Economic History. 62 (2): 457–488. doi:10.1017/S0022050702000566.

- Schweikart, Larry (1987). Banking in the American South from the Age of Jackson to Reconstruction. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1403-2.

- Smith, Walter Buckingham (1953). Economic Aspects of the Second Bank of the United States. Harvard University Press. pp. 21–178.

External links

- Common-place.org Special Issue on antebellum era recessions – Hard Times

- Economic History.net – Richard Sylla's review of Peter Temin's seminal work on the Jacksonian Economy

- "Panic of 1837". Primary source sets. Digital Public Library of America.