New states of Germany

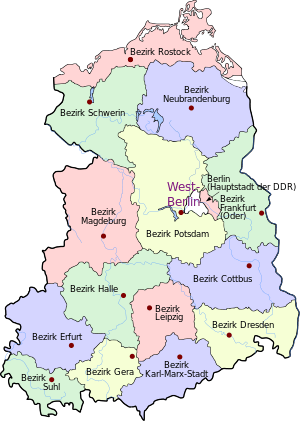

The new federal states of Germany (German: die neuen Bundesländer) are the five re-established states of former East Germany that acceded to the Federal Republic of Germany with its 10 states upon German reunification on October 3, 1990.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Germany | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Early history | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Early Modern period | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Unification | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| German Reich | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Contemporary Germany | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

The new states, which were dissolved by the East German government in 1952 and re-established in 1990, are Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. The state of Berlin, the result of a merger between East and West Berlin, is usually not considered one of the new states although many of its residents are former East Germans.

Germany currently has 16 states after reunification.

Culture

Persisting differences in culture and mentality among older East Germans and West Germans are often referred to as the "wall in the head" ("Mauer im Kopf").[1] Ossis (Easties) are stereotyped as racist, poor and largely influenced by Russian culture,[2] while Wessis (Westies) are usually considered snobbish, dishonest, wealthy, and selfish. The terms can be considered to be disparaging.

In 2009, a poll found that 22% of former East Germans (40% under 25) considered themselves "real citizens of the Federal Republic";[3] 62% felt they were no longer citizens of East Germany, but not fully integrated into the unified Germany; and around 11% would have liked to have re-established East Germany.[3] An earlier poll 2004 found that 25% of West Germans and 12% of East Germans wished reunification had not happened.[1]

Some East German brands have been revived to appeal to former East Germans who are nostalgic for the goods they grew up with.[4] Brands revived in this manner include Rotkäppchen, which holds about 40% of the German sparkling wine market, and Zeha, the sports shoe maker that supplied most of East Germany's sports teams as well as the Soviet Union national football team.[4]

Pornography and prostitution were outlawed in the GDR as forms of exploitation, and West Germans commonly believe that those who grew up in the GDR are more sexually inhibited than their western counterparts. Nonetheless, better access to higher education and jobs, along with free abortion, contraception and generous family policies, meant that East German women were more sexually active than before.[5] Another notable difference is the attitude towards naturism or Freikörperkultur (FKK) in Germany: while it existed in both East and West Germany, it was only a mass cultural phenomenon in the East wherein most people participated; this can still be seen at beaches of former East Germany compared to their West German counterparts.

More children are born out of wedlock in East Germany than in the West. In East Germany, 61% of births were from unmarried women compared to 27% in West Germany in 2009. Both states of Saxony-Anhalt and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania had the highest rates of birth outside wedlock at 64% each, followed by Brandenburg with 62%, Bavaria and Hesse at 26%, while the state of Baden-Württemberg had the lowest rate at 22%.[6]

Religion

Irreligion is predominant in the East Germany.[8][9][10] An exception is former West Berlin, which had a Christian plurality in 2016 (44.4% Christian and 43.5% unaffiliated). It also has a higher share of Muslims at 8.5%, compared to former East Berlin with only 1.5% self-declared Muslims as of 2016.[7] Christianity is the dominant religion of Western Germany, excluding Hamburg, which has a non-religious plurality.

| Religion by state, 2016[7] | Protestants | Catholics | Not religious | Muslims | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24.9% | 3.5% | 69.9% | 0.0% | 1.5% | |

| 14.3% | 7.5% | 74.3% | 1.5% | 2.4% | |

| 24.9% | 3.9% | 70.0% | 0.3% | 0.9% | |

| 27.6% | 4.0% | 66.9% | 0.3% | 1.1% | |

| 18.8% | 5.1% | 74.7% | 0.3% | 1.2% | |

| 27.8% | 9.5% | 61.2% | 0.0% | 1.5% | |

| Total | 24.3% | 5.2% | 68.8% | 0.3% | 1.4% |

"Pro Reli"

On April 26, 2009, a referendum (de) was held on whether Berlin pupils should be allowed to choose between the ethics class, a compulsory class introduced in all Berlin schools in 2006, or a religion class.[11] The SPD, the Left Party, and Greens supported the "Pro Ethics" camp for a "No" vote, stressing that the ethics class should remain compulsory, and pupils could voluntarily take an extra religion class alongside it if they chose; the CDU and FDP supported the "Pro Reli" camp for a "Yes" vote, wanting to give pupils a free choice.[11] In East Berlin, a majority of 74.62%[11][12] voted against the introduction of religious education. In West Berlin, 41.41% voted "No".[12] In total, 51.5% voted "No" and 48.4% voted "Yes".[11]

Economy

The economic reconstruction of eastern Germany (German: Aufbau Ost) proved to be longer-term than originally foreseen.[13] The standard of living and average annual income remain significantly lower in the new federal states.[14]

Reunification cost the federal government spent €2 trillion to reunify[13] and privatised 8,500 state-owned east Gemran enterprises..[15] Almost all East German industries were considered outdated while reunifying.[15] Since 1990, amounts between €100 billion and €140 billion have been transferred to the new states annually.[15] More than €60 billion were spent supporting businesses and building infrastructure in the years 2006-2008.[16]

A €156 billion economic plan, Solidarity Pact II, was enforced in 2005 and provided the financial basis for the advancement and special promotion of the economy of the new federal states until 2019.[13] The "solidarity tax", a 5.5% surcharge on the income tax, was implemented by the Kohl government to matchthe infrastructure of the new states to the levels of the western ones[17] and to apportion the cost of unification and the expenses of both the Gulf War and European integration. The tax, which raises €11 billion annually, was planned to remain in force until 2019.[17]

Since reunification, the unemployment rate in the east has doubled that of the west. The unemployment rate reached 12.7%[18] in April 2010, after reaching a maximum of 18.7% in 2005. In the decade 1999-2009, economic activity per person rose from 67% to 71% of western Germany.[16] Wolfgang Tiefensee, the minister then responsible for the development of the new federal states, said in 2009: "The gap is closing."[16] Eastern Germany is also the part of the country that was least affected by the 2007-2008 financial crisis.[19]

All the new federal states, excluding Berlin, qualify as Objective 1 development regions within the European Union and were eligible to receive investment subsidies of up to 30% until 2013.

Infrastructure

The "German Unity Transport Projects" (Verkehrsprojekte Deutsche Einheit, VDE) is a programme launched in 1991 that is intended to upgrade the infrastructure of eastern Germany and modernize transport links between the old and new federal states.[20] It consists of nine railway projects, seven motorway projects, and one waterway project with a total budget of €38.5 billion. As of 2009, all 17 projects were under construction or have been completed.[21] The construction of new railway lines and high-speed upgrades of existing lines reduced journey times between Berlin and Hanover from over four hours to 96 minutes.[22] Many railway lines (branches and main lines) have been closed by the unified Deutsche Bahn (German Railways) because of increased car usage and depopulation. The VDE states that some main lines are still not finished or upgraded, with the Leipzig-Nuremberg line (via Erfurt and part of the Munich-Berlin route) scheduled to come on-line in December 2017, almost three decades after reunification. Some lines, including those connecting large cities, are in a worse state then they were in the 1930s, with travel time from Berlin to Dresden slower in 2015 than in 1935.

Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau GmbH, (English: German Unity Road Construction Company) (DEGES) is the state-owned project management institution responsible for the construction of approximately 1,360 km of federal roads within the VDE with a total budget of €10.2 billion. It is also involved in other transport projects, including 435 km of roads costing about €1,760 million as well as a city tunnel in Leipzig costing €685 million.[23]

The Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2003 includes plans to extend the A14 motorway from Magdeburg to Schwerin and to build the A72 from Chemnitz to Leipzig.[21]

Private ownership rates of cars have increased since 1990: in 1988, 55% of East German households had at least one car; in 1993 it rose to 67% and 71% in 1998, compared to the West German rates of 61% in 1988, 74% in 1993, and 76% in 1998.[24][25]

Politics

Unlike the West, there was a three-party system (SPD, CDU, PDS/The Left) until the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) formed,[26][27][28] creating a four-party system.[29] Since 2009 at least four factions have been represented in each of the East German regional parliaments, six in Saxony. In 1998/1999, for example, only one of the regional parliaments included more than three factions.[30]

In the East, there is usually a low voter turnout. The East German Länder—except for the regional conference of the heads of government of the East German states (MPK-Ost)[31]—do not have joint state or public representation.

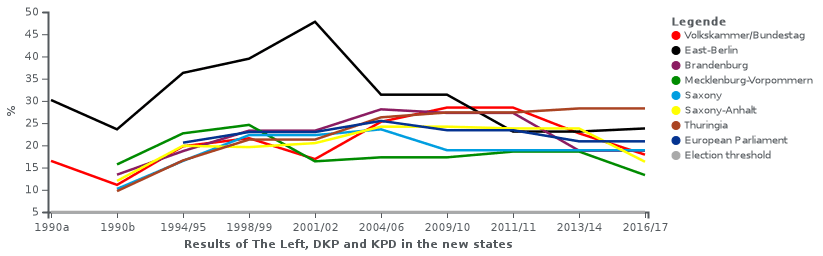

Far left

The democratic socialist party, The Left (Die Linke, successor to the Party of Democratic Socialism, the GDR state party's successor) has been successful throughout eastern Germany, perhaps as a result of the continued disparity of living conditions and salaries compared with western Germany, and high unemployment.[32] Ever since it associated with the WASG, The Left frequently loses in state elections and has been losing members since 2010.[33]

Historically, in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, the strongholds of the SPD, USPD, and KPD were Thuringia, Brandenburg, Berlin, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony.

The Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), and The Left from 2005, have gained the following vote shares in recent elections:

| Election | Vote percentages |

|---|---|

| 1990 East German general election | 16.4%, Communist Party of Germany (KPD) 0.1% |

| 1990 all-German federal election | East 11.1%, West 0.2% |

| 1990 State elections | East Berlin 30.1%, KPD 0.2%; Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 15.7%; Saxony 10.2%; Saxony-Anhalt 12.0%; Thuringia 9.7%; East Berlin 23.6% |

| 1994 federal election | East 19.8%, West 1% |

| 1994 state elections | 18.7% in Brandenburg; 19.9% in Saxony-Anhalt; Saxony 16.5%; Thuringia 16.6%; 22.7% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

| 1995 Berlin state election | in East Berlin the PDS was the biggest party with 36.3%. |

| 1998 federal election | East 21.6%, West 1.2%. |

| 1998–99 state elections | 23.3% in Brandenburg; 19.6% in Saxony-Anhalt; Saxony 22.2%, KPD 0.1%; Thuringia 21.3%; 24.4% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; 39.5% in East Berlin. |

| 2001–02 state elections | 16.4% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; 20.4%, KPD/DKP 0.1% in Saxony-Anhalt; 47.6%, 0.2% DKP in East Berlin. |

| 2002 federal election | East 16.9%, West 1.1% |

| 2005 federal election | East 25.3%, West 4.9% |

| 2004–06 state elections | 16.8% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (+0.5% WASG), 24.1% in Saxony-Anhalt and 28.1% (+3.3% WASG) in East Berlin (–19.5%). |

| 2009 federal election | East 28.5% (The Left became the strongest force in Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt); West 8.3%. |

| 2009 state elections | 20.6% in Saxony, 27.2% in Brandenburg and 27.4% in Thuringia |

| 2011 state elections | 18.6% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 23.7% in Saxony-Anhalt and 22.7% in East Berlin. |

| 2013 federal election | East 22.7%, West 5.2%. |

| 2014 state elections | 18.9% in Saxony, 28.2% in Thuringia and 18.6% in Brandenburg (–8.6%). |

| 2014 European Parliament election | German Communist Party (DKP) had its strongest vote in Eastern Germany (0.2% in East,[34] 0.0% in West[35]). |

| 2016 state elections | 16.3% in Saxony-Anhalt, 13.2% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and 23.4% in Berlin |

| 2017 federal election | East 17.8%; West 7.4%. |

After losing votes to the AfD, the Left plans to establish a regional group in East Germany.[36][37][38]

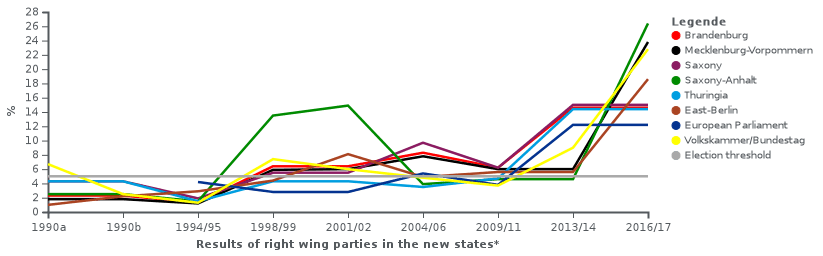

Far right

After 1990, far-right and German nationalist groups gained followers. Some sources claim mostly among people frustrated by the high unemployment and the poor economic situation.[39] Der Spiegel also points out that these people are primarily single men and that there may also be socio-demographic reasons.[40] Since around 1998 the moved from the south of Germany to the east.[41][42][43][44]

The headquarters of the Deutschkonservative Partei (English: German Conservative Party) (DKP), Deutschnationale Volkspartei (English: German National People's Party) (DNVP) and Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (English: Nazi Party) (NSDAP) were in Pomerania, Lower Silesia, East Prussia, and Brandenburg.

The far-right party Deutsche Volksunion (English: German People's Union) (DVU) formed in 1998 in Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg since 1999. A study from the University of Berlin from 1998/99 reports a right-wing extremist recruitment potential of 13% for all of Germany, and 12% for West Germany and 17% for East Germany.[45]

In May 2001, the Düsseldorf Federal Party Congress of the FDP decided on "Strategy 18" (that was proposed by Jürgen Möllemann) as a goal. Möllemann supported Jamal Karsli who is criticized as anti-Semitic,[46] and was criticized by then-FDP leader Guido Westerwelle that he wanted to make the FDP a right-wing populist party[47] and received support from Jörg Haider.[48] The name referred to the election goal of tripling the share of electoral votes from 6% to 18%. In the midst of controversy over a possibly associated right-wing populist orientation, the FDP ultimately achieved 7.4% and moved away from the course after the election, but gained in all new states in 2002 between the highest of 3.6% in Saxony and the lowest of 2.4% in East Berlin.[49][50] After failing at the 2002 Saxony-Anhalt state election, the right-wing populist[51][52] Schill party just short of the 5% threshold (4.5%) and the FDP moved into the state parliament. In the East-Berlin election, 2001 it won against the FDP at 5.3% (+4.2%) and fell short of the 5% threshold in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (4.7%).

The National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) won 9.2% of the vote in the 2004 state parliament elections in Saxony, with the party taking eight seats in the state parliament in Dresden after the 13 seats held by the Social Democrats. In 2004 the DVU won votes in Brandenburg (+0.8%). The NPD represented in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern since 2006.[53]

In the 2009 Saxony state election, the NPD lost votes (-3.6%) and seats (-4),[54] while in the same month the German People's Union lost its representation in the Landtag of Brandenburg.[55]

A survey of 14- to 25-year-olds carried out by the Forsa opinion poll institute in 2007 discovered that one out of two youths in eastern Germany believe that National Socialism had "its good sides".[39]

In 2009, Junge Landsmannschaft Ostdeutschland, supported by the NPD, organized a march on the anniversary of the Bombing of Dresden in World War II. There were 6,000 Nationalists that were met by tens of thousands of ″anti-Nazis″ and several thousand police.[56]

The Free Voters of Germany emerged in 2009 from the Land Brandenburg regional branch of Free Voters, after being excluded because of "signs of right infiltration" from the Federal Association of Free Voters Germany.[57]

In the 2011 Mecklenburg-Vorpommern state elections, the NPD lost 1.3% and 1 seat but won in Saxony-Anhalt compared with the DVU's 1.6%.

Alternative for Germany (2013–present)

Alternative for Germany (AfD) had the most votes in Eastern Germany in the 2013 German federal elections and in 2017.[58] The party is seen as harbourring anti-immigration views.[59]

The Pegida has its focus in East Germany.[60] A survey by TNS Emnid reports that in mid-December 2014, 53% of East Germans in each case sympathised with the PEGIDA demonstrators. (48% in the West)[61]

In 2014, the NPD in Saxony fell short on the threshold (4.9%), but AfD entered the state parliaments in Saxony, Brandenburg, and Thuringia.

In 2016, AfD reached at least 17% in Saxony-Anhalt,[62] Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (where the NPD lost all seats)[63] and East Berlin;[64] they won up to 15% in Baden-Württemberg,[65] Rhineland-Palatinate[66] and West Berlin.[64]

In 2015, Rhineland-Palatinate interior minister Roger Lewentz said the former communist states were ″more susceptible″ to ″xenophobic radicalization″ because Eastern Germany had not had the same exposure to foreign people and cultures over the decades that the people in the West of the country have had.[67]

In the 2017 Federal Election, AfD received approximately 22% of the votes[68] in the East and approximately 11%[69] in the West.[70] The AfD became the most popular party in Saxony.[71]

*With the votes of the FDP gains of 2001/02.[72]

Protest vote

Non-mainstream parties, particularly the AfD and The Left,[73][74][75] receive a large number of protest votes in Eastern Germany, which causes voter shifting from left to right and vice versa.[76]

The Pirate Party Germany was chosen slightly more frequently in the East (10.1 percent) than in the West (8.1 percent) of Berlin. Among those under 30 years of age in East Berlin, the pirates with were the second most popular party with 20 percent of the votes.[77] For example, none of the parties elected to the Berlin House of Representatives in 2011 lost a high proportion of their voters to the AfD as the pirates at the next election in 2016 (16%).[78][79] Other findings also suggest that some of their voters, like the AfD, regard the Pirate Party primarily as a protest party.[73][80]

The election slogans of the DVU in the regional elections in Saxony-Anhalt in 1998 were directed primarily against the already represented in parliament politicians: "Not the people - the political bigwigs, will dole!" And "German, let's not make the sow you. DVU - The protest in the election against dirty things from above ". In particular, politically dissatisfied people were advertised with the slogan "vote protest - vote German." [81] At the time, the DVU had 12.9% of the votes.

Independence

History

In 1991, the PDS demanded the right for Thuringia to leave the Federal Republic of Germany in its draft of the constitution, which ultimately did not pass.[82][83]

Tatjana Festerling was a leader in the Dresden Pegida demonstrations from February 2015 to mid-April 2016 after Kathrin Oertel withdrew. She demanded the "Säxit"—the secession of Saxony from the Federal Republic of Germany—on October 12, 2015, after she had already demanded the rebuilding of German border installations on March 9, 2015.[84][85]

Opinion polls

| Polling firm | Fieldwork date | Sample size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YouGov[86] | 2017 | 2076 | 19 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 22 |

| infratest dimap | 2014 | 2020 | 16 | |||||

| Insa-Consulere[87] | 2014 | ~1000 | 19 (partially) | |||||

| Emnid | 2010 | 1001 | 15 (+8 partially) | |||||

| Sozialwissenschaftliche Forschungszentrum Berlin-Brandenburg | 2010 | ~1900 | 10 | |||||

| Emnid | 2009 | 1208 | 57 (partially) | |||||

| RP Online | 2009 | 2892 | 11 | |||||

| Infratest dimap | 2007 | ? | 23 | |||||

| Institut für Marktforschung Leipzig | 2007 | 1001 | 18 | |||||

| mitBERLIN | 1996 | 6000 | 63.6 | |||||

| Infratest | 1996 | 2000 | 22 | |||||

| Infratest | 1990 | ? | 11 | |||||

Demographic development

The former East German states have experienced high rates of depopulation and low birth rates since 1990 with some recovery in recent years. About 1.7 million people (or 12% of the population) have left the new federal states since the fall of the Berlin Wall.[16] A disproportionately high number of them were women under 35.[40] About 500,000 women under the age of 30 have left for western Germany in the past 15 years.[88]

After 1990, the fertility rate in the East dropped to 0.77 . In 2006, the rates in the new states (1.30) approached those in the West (1.34) and is now higher (1.64 vs 1.60 in West, the year 2016).[89][90] Since 1989, about 2,000 schools have closed because of a low demographic in children.[16]

In some regions, the number of women between the ages of 20 and 30 has dropped by more than 30 percent.[16] In 2004, in the age group 18-29 (statistically important for starting families) there were only 90 women for every 100 men in the new federal states (including Berlin).[91] In parts of the state of Thuringia, there are 82 women for every 100 men.[88] The town of Königstein has the biggest demographic imbalance in Europe between young men and women,[88] compared to many areas in Europe as many cities across the continent also have gender disparity.[92] Local leaders raised their concerns as a large imbalance of men to women is usually linked to historical social instabilities and increased crime rates.[88]

Around 300,000 homes were demolished in recent years. In parts of eastern Germany, wolves and lynxes have reappeared after many decades.[88]

Demographic evolution

.svg.png)

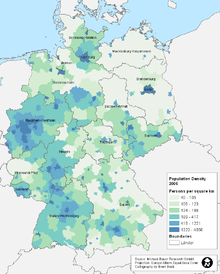

Brandenburg had a population of 2,660,000 in 1989 and 2,447,700 in 2013.[93] It has the second-lowest population density in Germany. In 1995, it was the only new state to experience population growth, aided by nearby Berlin.[94]

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern had a population of 1,970,000 in 1989 and 1,598,000 in 2013,[93] with the lowest population density in Germany. The local Landtag held several inquiries on overpopulation trends after the opposition requested an annual report on the topic.[94]

Saxony had a population of 5,003,000 in 1989, which fell to 4,044,000 in March 2013.[93] It remains the most populated among the five new states. The proportion of the population under 20 years of age fell from 24.6% in 1988 to 19.7% in 1999.[94] Dresden and Leipzig are among the fastest-growing cities in Germany, both raising their population over half a million inhabitants again and in strong contrast to the other districts of Saxony.

Saxony-Anhalt had a population of 2,960,000 in 1989 and 2,253,000 in 2013.[93] The state has a long history of demographic decline: its current territory had a population of 4,100,000 in 1945. The emigration already began during the GDR years.[94]

Thuringia had a population of 2,680,000 in 1989, and 2,166,000 in March 2013.[93] In Thuringia, the migration had less of an impact than the decrease in the fertility rate. Former Minister-President Bernhard Vogel called for the exodus of skilled workers and young people to stop.[94]

The total change in the population of former East Germany is from 15.273 million in 1989, just before reunification, to 12.509 million in 2013, a decrease of 18.1%.

Migration

There are more migrants in former West Germany than in former East Germany. All of the East German states bar Berlin have populations where 90-95% of people do not have a migrant background.[95][96][97]

Major cities

| Federal capital | |

| State capital |

| Rank | City | Pop. 1950 |

Pop. 1960 |

Pop. 1970 |

Pop. 1980 |

Pop. 1990 |

Pop. 2000 |

Pop. 2010 |

Area [km²] |

Density per km² |

Growth [%] (2000– 2010) |

surpassed 100,000 |

State (Bundesland) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3,336,026 | 3,274,016 | 3,208,719 | 3,048,759 | 3,433,695 | 3,382,169 | 3,460,725 | 887,70 | 3,899 | 2.32 | 1747 | ||

| 2. | 494,187 | 493,603 | 502,432 | 516,225 | 490,571 | 477,807 | 523,058 | 328,31 | 1,593 | 9.47 | 1852 | ||

| 3. | 617,574 | 589,632 | 583,885 | 562,480 | 511,079 | 493,208 | 522,883 | 297,36 | 1,758 | 6.02 | 1871 | ||

| 4. | 293,373 | 286,329 | 299,411 | 317,644 | 294,244 | 259,246 | 243,248 | 220,84 | 1,101 | −6.17 | 1883 | ||

| 5. | 289,119 | 277,855 | 257,261 | 232,294 | 247,736 | 247,736 | 232,963 | 135,02 | 1,725 | −5.96 | 1890 | ||

| 6. | 260,305 | 261,594 | 272,237 | 289,032 | 278,807 | 231,450 | 231,549 | 200,99 | 1,152 | 0.04 | 1882 | ||

| 7. | 188,650 | 186,448 | 196,528 | 211,575 | 208,989 | 200,564 | 204,994 | 269,14 | 762 | 2.21 | 1906 | ||

| 8. | 133,109 | 158,630 | 198,636 | 232,506 | 248,088 | 200,506 | 202,735 | 181,26 | 1,118 | 1.11 | 1935 | ||

| 9. | 118,180 | 115,004 | 111,336 | 130,900 | 139,794 | 129,324 | 156,906 | 187,53 | 837 | 21.33 | 1939 | ||

| Rank | City | Pop. 1950 |

Pop. 1960 |

Pop. 1970 |

Pop. 1980 |

Pop. 1990 |

Pop. 2000 |

Pop. 2010 |

Area [km²] |

Density per km² |

Growth [%] (2000– 2010) |

surpassed 100,000 |

State (Land) |

See also

- Ostalgie

- Wessi

- East German jokes

- Old states of Germany

References

- "Breaking Down the Wall in the Head". Deutsche Welle. 2004-10-03. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Cameron Abadi (2009-08-07). "The Berlin fall". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2009-08-09. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Noch nicht angekommen - Survey of 2900 adults in the New Länder in summer 2008". Berliner Zeitung. 21 January 2009. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- "East German brands thrive 20 years after end of Communism". Deutsche Welle. 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Balmer, Etienne (2009-10-19). "'Women's love lives were better in East Germany before the Berlin Wall fell'". Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "One third of children born out of wedlock". 12 August 2011.

- "Konfession, Bundesland - weighted (Kumulierter Datensatz)". Politbarometer 2016: Question V312.F1. 2016 – via GESIS.

- "Ostdeutschland: Wo der Atheist zu Hause ist". Focus. 2012. Retrieved 2017-11-11.

- "WHY EASTERN GERMANY IS THE MOST GODLESS PLACE ON EARTH". Die Welt. 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- "East Germany the "most atheistic" of any region". Dialog International. 2012. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- Antoine Verbij (27 April 2009). "Berlijn blijft een heidense stad". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Fahrun, Joachim (2009-04-26). "Der Westen stimmt mit Ja - der Osten mit Nein" (in German). Berliner Morgenpost. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- "Aufbau Ost, economic reconstruction in the East". Deutsche Bundesregierung. 2007-08-24. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- "The Price of a Failed Reunification". Spiegel International. 2005-09-05. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- Boyes, Roger (2007-08-24). "Germany starts recovery from €2,000bn union". Times Online. London. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- Kulish, Nicholas (2009-06-19). "In East Germany, a Decline as Stark as a Wall". New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- Hall, Allan (2007-08-01). "Calls grow to lift burden of Germany's solidarity tax". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- "Current statistics of the Bundesagentur für Arbeit comparing east and west". Archived from the original on 2010-05-23. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- "Eastern Germany Less Hard Hit than the West". Spiegel International. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Infrastructure for unified Germany". Federal Government Commissioner for the New Federal States. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Draft Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Firmenprofil". DEGES. Archived from the original on 2009-05-25. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Wilhelm Hinrichs: Die Ostdeutschen in Bewegung – Formen und Ausmaß regionaler Mobilität in den neuen Bundesländern Archived 2004-08-29 at the Wayback Machine (PDF-Dokument)

- bpb: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Die DDR in den siebziger Jahren

- Steffen Schoon: Wählerverhalten und Strukturmuster des Parteienwettbewerbs, in: Steffen Schoon, Nikolaus Werz (Hrsg.): Die Landtagswahl in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2006, Rostock 2006, S. 9.

- http://www.kai-arzheimer.com/wahlforschung/vl-wve-08-screen.pdf

- http://www.lotharprobst.de/fileadmin/user_upload/redakteur/Publikationen/Ostdeutsches%20Parteiensystem%20und%20Entwicklung%20der%20Gruenen.pdf.

- "Landtagswahlen 2016: AfD wird Ost-Volkspartei, FDP läuft sich für Bundestag warm". www.wiwo.de.

- Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Parteien und Parteienwettbewerb in West- und Ostdeutschland - bpb". www.bpb.de.

- Regionalkonferenz der Regierungschefin und der Regierungschefs der ostdeutschen Länder (MPK-Ost) Archived 2012-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Webseite der Sächsischen Staatskanzlei (Ministerpräsident). Abgerufen am 18. April 2013.

- "DIE LINKE: Ostdeutschland".

- "Linke verliert massiv Mitglieder".

- "Wahlen zum Europäischen Parlament in den Neuen Bundesländern und Berlin-Ost". www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de.

- "Wahlen zum Europäischen Parlament in den alten Bundesländern". www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de.

- tagesschau.de. "Nach der Bundestagswahl: Linkspartei will Protestwähler zurückholen". tagesschau.de.

- "Landesgruppe Ost soll Protestwähler zurückholen". www.rbb24.de.

- Nachrichtenfernsehen, n-tv. "Linke plant Landesgruppe Ost im Bundestag".

- Boyes, Roger (2007-08-20). "Neo-Nazi rampage triggers alarm in Berlin". The Times. London. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Lack of Women in Eastern Germany Feeds Neo-Nazis". Spiegel International. 2007-05-31. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Es war nicht immer der Osten – Wo Deutschland rechts wählt"./

- Pickel, Gert; Walz, Dieter; Brunner, Wolfram (2013-03-09). Deutschland nach den Wahlen: Befunde zur Bundestagswahl 1998 und zur Zukunft des deutschen Parteiensystems. ISBN 9783322933263.

- Steglich, Henrik (2010-04-28). Rechtsaußenparteien in Deutschland: Bedingungen ihres Erfolges und Scheiterns. ISBN 9783647369150.

- "Rechtsextremismus - ein ostdeutsches Phänomen?".

- Nach Iris Huth: Politische Verdrossenheit, Band 3, 2004, S. 226.

- Möllemanns und Westerwelles unerträgliche Angriffe gegen Friedman, Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland, 22 May 2002.

- "FDP wirft Möllemann Rechtspopulismus vor".

- "Möllemann bekommt Beifall von Haider".

- "Veränderung der Zweitstimmenanteile der FDP in den Ländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2002 im Vergleich zu 1998". FDP/DVP Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- "Bundestagswahlen – Berlin-Ost". wahlen-in-deutschland.de. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- Dürr, Tobias (2003). On "Westalgia": Why West German Mentalities and Habits Persist in the Berlin Republic. The Spirit of the Berlin Republic. Berghahn Books. p. 47.

- Søe, Christian (2005). A False Dawn for Germany's Liberals: The Rise and Fall of Project 18. Precarious Victory. p. 117.

- "Right-Wing Extremists Find Ballot-Box Success in Saxony". Spiegel International. 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Landtagswahl in Sachsen". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. Archived from the original on 2009-10-12. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- "Landtagswahl Brandenburg 2009". Tagesschau. Archived from the original on 2009-09-30. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Patrick Donahue. "Skinheads, Neo-Nazis Draw Fury at Dresden 1945 'Mourning March'". Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- Freie Wähler schließen Zwei Landesverbände Wegen Rechtskurs aus, pr-inside.com (Associated Press), 4. April 2009.

- Oltermann, Philip (28 September 2017). "'Revenge of the East'? How anger in the former GDR helped the AfD" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Troianovski, Anton (21 September 2017). "Anti-Immigrant AfD Party Draws In More Germans as Vote Nears" – via www.wsj.com.

- "Pegida – "Ein überwiegend ostdeutsches Phänomen"" (in German). Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- Mehrheit der Ostdeutschen zeigt Verständnis. In: N24, 14. Dezember 2014.

- Statistisches Landesamt Sachsen-Anhalt: Wahl des 7. Landtages von Sachsen-Anhalt am 13. März 2016, Sachsen-Anhalt insgesamt

- "Wahl zum Landtag in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2016" (in German). Statistisches Amt MV: Die Landeswahlleiterin. 2016-09-04. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- tagesschau.de. "tagesschau.de". wahl.tagesschau.de.

- Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg: Endgültiges Ergebnis der Landtagswahl am 13. März 2016, Land Baden-Württemberg

- Landesergebnis Rheinland-Pfalz - Endgültiges Ergebnis Der Landeswahlleiter Rheinland-Pfalz

- (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Eastern Germany 'more susceptible' to 'xenophobic radicalization' - News - DW - 31.08.2015". DW.COM.

- "Neue Bundesländer und Berlin-Ost Zweitstimmen-Ergebnisse". www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de.

- "Alte Bundesländer und Berlin-West Zweitstimmen-Ergebnisse". www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de.

- "Bundestagswahl 2017".

- "AfD ist in Sachsen jetzt die stärkste Kraft".

- "Bundestagswahlen – Neue Bundesländer und Berlin-Ost". wahlen-in-deutschland.de. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- Iris Huth: Politische Verdrossenheit. Erscheinungsformen und Ursachen als Herausforderungen für das Politische System und die Politische Kultur der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im 21. Jahrhundert, Dissertation Universität Münster 2003, LIT Verlag, Münster 2004, (Politik und Partizipation 3), S. 170.

- "Vor allem im Osten stark: AfD könnte Linke als Protestpartei ablösen".

- "Thüringer Soziologe: "AfD-Erfolg im Osten ist Ausdruck von Protest"".

- "Protestwähler: Wie AfD und Linke in Berlins Osten um Stimmen konkurrieren".

- Wahlanalysen. Forschungsgruppe Wahlen; abgerufen am 1. Oktober 2011

- Infratest dimap: Analysen Zu den Wählerwanderungen in Berlin 2016, abgerufen am 29. September 2016.

- Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 20. September 2016, S. 10.

- Felix Neumann: Plattformneutralität. Zur Programmatik der Piratenpartei. In: Oskar Niedermayer (Hrsg.): Die Piratenpartei. Springer, Wiesbaden 2013, S. 175.

- Steffen Kailitz (2004), "3.3 "Deutsche Volksunion"", books.google.de%5d Politischer Extremismus in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Eine Einführung Check

|url=value (help) (in German) (1. ed.), Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, p. 44, ISBN 3-531-14193-7, retrieved 2010-12-12 - Zander, Peter (15 March 2010). "Weimarer Verhältnisse in der Berliner Republik" – via www.welt.de.

- Thüringer Landtag, Drucksache 1/678

- Pegida beschwört den Bürgerkrieg und fordert den Säxit coloRadio, 15. Oktober 2015.

- "Ö weiö!: Pegida-Frau droht mit "Säxit"". 14 October 2015 – via Spiegel Online.

- WELT, DIE (17 July 2017). "Umfrage in Bundesländern: Wo die meisten Einwohner für die Abspaltung von Deutschland sind" – via www.welt.de.

- Germany, Süddeutsche de GmbH, Munich. "Umfrage: Gut jeder sechste Deutsche will Mauer zurück". Süddeutsche.de.

- Burke, Jason (2008-01-27). "Slow death of a small German town as women pack up and head west". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- publisher. "State & society - Births - Average number of children per woman - Federal Statistical Office (Destatis)". www.destatis.de.

- "Startseite - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis)". destatis.de. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- "The Demographic State of the Nation" (PDF). Berlin Institute for Population and Development. 2006. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Where do young European women go?".

- "Gemeinsames Datenangebot der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder". Archived from the original on 2017-09-24. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- "Abwanderung aus den neuen Bundesländern von 1989 bis 2000". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. 2001. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- "Die Rechten ziehen in den Osten, Ausländer in den Westen".

- Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Ausländische Bevölkerung nach Ländern - bpb". www.bpb.de.

- "Ausländeranteil in Deutschland nach Bundesländern". www.laenderdaten.de.