Moshe Feinstein

Moshe Feinstein or Moses Feinstein[1] (Hebrew: משה פײַנשטיין Moshe Faynshteyn; March 3, 1895 – March 23, 1986) was an American Orthodox rabbi, scholar, and posek (authority on halakha—Jewish law), regarded by many as the de facto supreme halakhic authority for observant Jews in North America. His rulings are often referenced in contemporary rabbinic literature. Feinstein served as president of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis, Chairman of the Council of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of the Agudath Israel of America, and head of Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem in New York.

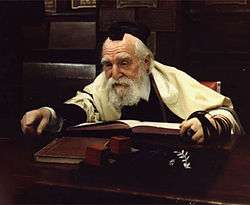

Rabbi Moshe Feinstein | |

|---|---|

Moshe Feinstein at his desk in the bais medrash of Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem. | |

| Born | March 3, 1895 |

| Died | March 23, 1986 (aged 91) |

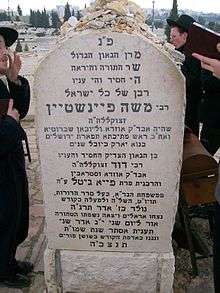

| Resting place | Har HaMenuchot, Israel 31.8°N 35.183333°E |

| Other names | Rav Moshe, Reb Moshe |

| Occupation | Rabbi, Posek |

| Employer | Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem |

| Known for | Igros Moshe, various rulings in Jewish law |

| Spouse(s) | Shima Kustanovitch |

| Children | Pesach Chaim Feinstein Dovid Feinstein Reuven Feinstein Shifra Tendler Faye Shisgal |

Widely acclaimed in the Orthodox world for his gentleness and compassion, Feinstein is commonly referred to simply as "Reb Moshe"[2][3] (or "Rav Moshe").[4][5]

Biography

Moshe Feinstein was born, according to the Hebrew calendar, on the 7th day of Adar, 5655 (traditionally the date of birth and death of the biblical Moshe) in Uzda, near Minsk, Belarus, then part of the Russian Empire. His father, David Feinstein, was the rabbi of Uzdan and a great-grandson of the Vilna Gaon's brother. His mother was a descendant of talmudist Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller, the Shlah HaKadosh, and Rashi. He studied with his father, and also in yeshivas located in Slutsk and Shklov. He also had a close relationship with his uncle, Yaakov Kantrowitz, rabbi of Timkovichi, whom he greatly revered and considered his mentor.

Feinstein was appointed rabbi of Lubań, where he served for sixteen years. He married Shima Kustanovich in 1920, and had four children (Pesach Chaim, Fay Gittel, Shifra, and David), before leaving Europe.[6] Pesach Chaim died in Europe, and another son, Reuven, was born in the United States. Under increasing pressure from the Soviet regime, he moved with his family to New York City in 1936, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Settling on the Lower East Side, he became the rosh yeshiva of Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem. He later established a branch of the yeshiva in Staten Island, New York, now headed by his son Reuven Feinstein. His son Dovid Feinstein heads the Manhattan branch.

He was president of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada, and chaired the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudath Israel of America from the 1960s until his death. Feinstein also took an active leadership role in Israel's Chinuch Atzmai.

Feinstein was revered by many as the Gadol Hador (greatest Torah sage of the generation), including by Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, Yonasan Steif, Elyah Lopian, Aharon Kotler, Yaakov Kamenetsky, and Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, even though several of them were far older than he. Feinstein was also recognized by many as the preeminent Torah sage and posek of his generation, and people from around the world called upon him to answer their most complicated halachic questions.

Notable decisions

Owing to his prominence as an adjudicator of Jewish law, Feinstein was asked the most difficult questions, in which he issued a number of innovative and controversial decisions. Soon after arriving in the United States, he established a reputation for handling business and labor disputes. For instance, he wrote about strikes, seniority, and fair competition. Later, he served as the chief Halakhic authority for the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists, indicative of his expertise in Jewish medical ethics. In the medical arena, he opposed the early, unsuccessful heart transplants, although it is orally reported that in his later years, he allowed a person to receive a heart transplant (after the medical technique of preventing rejection was improved). On such matters, he often consulted with various scientific experts, including his son-in-law Moshe David Tendler, who is a professor of biology and serves as a rosh yeshiva at Yeshiva University.[7] As one of the prominent leaders of American Orthodoxy, Feinstein issued opinions that clearly distanced his community from Conservative and Reform Judaism.[8] He faced intense opposition from Hasidic Orthodoxy on several controversial decisions, such as rulings on artificial insemination and mechitza. In the case of his position not to prohibit cigarette smoking, though he recommended against it and prohibited second-hand smoke, other Orthodox rabbinic authorities disagreed. Even his detractors, while disagreeing with specific rulings, still considered him to be a leading decisor of Jewish law. The first volume of his Igrot Moshe, a voluminous collection of his halachic decisions, was published in 1959.[9] He made noteworthy decisions on the following topics:

- Artificial insemination from a non-Jewish donor (EH I:10,71, II:11, IV:32.5)[10]

- Ascending the Temple Mount nowadays (OH II:113)[11]

- Cosmetic surgery (HM II:66)[12]

- Bat Mitzvah for girls (OH I:104 (1956), OH II:97 (1959), OH IV:36)[13]

- Brain death as an indication of death under Jewish law. (YD II:146,174, III:132, IV:54)[14] However, this is disputed.

- Cholov Yisroel Permitted reliance (at least under extenuating circumstances, such as if no Cholov Yisroel milk is available[15]) on U.S. government agency supervision in ensuring that milk was reliably kosher, and it is as if Jews had personally witnessed it (YD I:47). This was a highly controversial ruling disputed by prominent peers of Feinstein.[16]

- Cheating (he forbid it) for the N.Y. Regents exams (HM II:30)[17]

- Classical music in religious settings (YD II:111)

- Commemorating the Holocaust, Yom ha-Shoah (YD IV:57.11)

- Conservative Judaism, including its clergy and schools (e. g., YD II:106–107)[18]

- Donating blood for pay (HM I:103)

- Education of girls (e. g., YD II:109, YD II:113 YD III:87.2)[19]

- End-of-life medical care[14]

- Eruv projects in New York City

- Financial ethics (HM II:29)[20]

- Hazardous medical operations[14]

- Heart transplantation (YD 2:174.3)[14]

- Labor union and related employment privileges (e. g., HM I:59)

- Mehitza (esp. OH I:39)[21]

- Mixed-seating on a subway or other public transportation (EH II:14)

- Psychiatric care (YD II:57)

- Separation of conjoined twins who were fused all the way from the shoulder to the pelvis and shared one heart. It is during this case that C. Everett Koop, the 13th Surgeon General of the United States, said "The ethics and morals involved in this decision are too complex for me. I believe they are too complex for you as well. Therefore I referred it to an old rabbi on the Lower East Side of New York. He is a great scholar, a saintly individual. He knows how to answer such questions. When he tells me, I too will know."[22]

- Shaking hands between men and women (OH I:113; EH I:56; EH IV:32)[23]

- Smoking marijuana (YD III:35)

- Tay–Sachs disease fetus abortion, esp. in debate with Eliezer Waldenberg[24]

- Smoking cigarettes[25]

- Veal raised in factory conditions (EH IV, 92:2)

- Permitted remarriage after Holocaust (EH I:44)

Note: Responsa in Igrot Moshe are cited in parentheses

Death

Feinstein died on March 23, 1986 (13th of Adar II, 5746). It has been pointed out that the 5746th verse in the Torah reads, "And it came to pass after Moshe had finished writing down the words of this Torah in a book to the very end." (Deuteronomy 31:24).[26] This is taken by some as a fitting epitaph for him.

His funeral in Israel was delayed by a day due to mechanical problems with the plane carrying his coffin, which then had to return to New York. His funeral in Israel was said to be the largest among Jews since the Mishnaic era, with an estimated attendance of 300,000 people (though others since then may have been bigger. Some sources put Ovadia Yosef's funeral attendance at over 850,000). Among the eulogizers in America were Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman, Dovid Lifshitz, Shraga Moshe Kalmanowitz, Nisson Alpert, Moshe David Tendler, Michel Barenbaum, and Mordecai Tendler, and the Satmar Rebbe. The son of the deceased, Reuven Feinstein, also spoke.

Feinstein was held in such great esteem that Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, who was himself regarded as a Torah giant, Talmid Chacham, and posek, refused to eulogize him, saying, "Who am I to eulogize him? I studied his sefarim; I was his talmid (student)."

Feinstein was buried on Har HaMenuchot in proximity to his teacher, Isser Zalman Meltzer;[3] his friend, Aharon Kotler; his son-in-law, Moshe Shisgal; the Brisker Rav, Rav Avraham Yoffen, and next to the Belzer Rebbe.

Prominent students

Feinstein invested much time molding select students to become leaders in Rabbinics and Halacha. Most are considered authorities in many areas of practical Halacha and Rabbinic and Talmudic academics. Some of those students are:

- Nisson Alpert (1927–1986), Rav of Agudath Israel of Long Island, New York

- Avrohom Blumenkrantz (1944–2007), author of The Laws of Pesach

- Elimelech Bluth, (d. 2019) (Brooklyn, NY), his devoted attendee and personal driver, Rav of Cong. Ahavath Achim of Flatbush, dean of Beth Medrash Ltorah V'Lhorah, and rabbi of Kensington

- Shimon Eider (d. 2007), posek and author (Lakewood, NJ)

- Dovid Feinstein (b. 1929), Rosh yeshiva of Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem in New York City, his son

- Reuven Feinstein (b. 1937), Rosh yeshiva of Yeshiva of Staten Island, New York, his son

- Shmuel Fuerst, Dayan of Chicago Rabbinical Council[27]

- Nota Greenblatt (b.1925), Av Beis Din of Vaad Hakehilos of Memphis, Tennessee

- Jackie Mason, comedian (New York City)[28]

- Michel Shurkin, maggid shiur (lecturer) in Yeshiva Toras Moshe Jerusalem, and author of Hararei Kedem and Meged Givos Olam

- Moshe Dovid Tendler, Rosh yeshiva at Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, and pulpit rabbi in Monsey, New York, his son-in-law

Works

Feinstein's greatest renown came from a lifetime of responding to halachic queries posed by Jews in America and worldwide. He authored approximately 2,000 responsa on a wide range of issues affecting Jewish practice in the modern era. Some responsa can also be found in his Talmudic commentary (Dibrot Moshe), some circulate informally, and 1,883 responsa were published in Igrot Moshe. Among Feinstein's works:

- Igrot Moshe; (Epistles of Moshe); pronounced Igros Moshe by Yiddish speakers such as Feinstein himself; a classic work of Halachic responsa. Consisting of 7 volumes published during his lifetime and considered necessary for every rabbi to have. Of these, the final, seventh volume was published in two different forms, the resulting variations found in a total of 65 responsa.[29] An additional 2 volumes were published posthumously from manuscripts and oral dictations that were transcribed by others.

- Dibrot Moshe (Moshe's Words); pronounced Dibros Moshe by Yiddish speakers such as Feinstein himself; a 14 volume work of Talmudic novellae with additional volumes being published by the Feinstein Foundation and being coordinated by his grandson, Mordecai Tendler.

- Darash Moshe (Moshe Expounds, a reference to Leviticus 10:16), a posthumously published volume of novellae on the weekly synagogue Torah reading. [Artscroll subsequently translated this as a two-volume English work.]

- Kol Ram (High Voice); 3 volumes, printed in his lifetime by Avraham Fishelis, the director of his yeshiva

Some of Feinstein's early works, including a commentary on the Talmud Yerushalmi, were lost in Communist Russia, though his first writings are being prepared for publication by the Feinstein Foundation.

Feinstein is known for writing, in a number of places, that certain statements by prominent rishonim which Feinstein found theologically objectionably were not in fact written by those rishonim, but rather inserted into the text by erring students.[30] According to Rav Dovid Cohen of Brooklyn, Feinstein attributed such comments to students as a way of politely rejecting statements by rishonim while still retaining full reverence for them as religious leaders of earlier generations.[31]

References

- "The Water's Fine, but Is It Kosher?". NYTimes.com. November 7, 2004.

- Reb Moshe: The Life and Ideals of HaGaon Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. ArtScroll. 1986. ISBN 97-81422610848.

- Marek Cejka; Roman Koran (2015). Rabbis of our Time: Authorities of Judaism. ISBN 1317605446.

Reb Moshe .. body .. to Jerusalem, .. funeral at ... Har Ha-Menuchot

- "This Day in Jewish history". Haaretz. March 3, 2013.

Rabbi Feinstein – known affectionately in the Orthodox world as "Rav Moshe"...

- "Story template 5769". Ascent Of Safed.

As soon as Rabbi Moshe Feinstein ... turned to Rav Moshe and ...

- "Great Leaders of Our People – Rav Moshe Feinstein". Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- "The Halakhic Definition of Life in a Bioethical Context". Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- For example, see Roth, Joel. The Halakhic Process: A Systematic Analysis, JTS: 1986, pp.71ff. Robinson (2001).

- Codex Judaica Mattis Kantor, Zichron Press, NY 2005, p.299

- Cohen, A. in JHCS

- Meyer, Gedalia; Messner, Henoch (2010). "Entering the Temple Mount—in Halacha and Jewish History". Hakirah (10). ISBN 0-9765665-9-1.

- Halperin (2006)

- See esp. Joseph (1995)

- Feinstein & Tendler (1996)

- https://collive.com/groundbreaking-letter-by-rav-feinstein-restricts-cholov-stam/

- Rav Yaakov Breisch in Chelkas Yaakov Vol.2 ch.37 stated that "all of his rationales are not sufficient to contradict a clear ruling of the Shulchan Aruch and halachic authorities...." Later in ch.37 and 38, Breisch extensively disputes various premises underlying the rationale for Feinstein's lenient ruling. See also Shu"t Beer Moshe Vol.4, ch.52, Kinyan Torah 1:38 for a more detailed listing of the many authorities disputing Feinstein's reasoning and conclusion.

- פיינשטיין, משה. אגרות משה חלק ז - חושן משפט חלק שני סימן ל. p. 244. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

הנה בדבר שאלתו על כותב האג״מ מה ששמע שבישיבות מתירין להתלמידים לגנוב את התשובות להשאלות במבחני הסיום שעושה המדינה (רידזענם) 'כדי להונות ולקבל את התעודות שגמרו בטוב, הנה דבר זה איסור לא רק מדינא דמלכותא אלא מדין התורה, ואין זה רק גניבת דעת שג״כ אסור כדאמר שמואל בחולין דף צ״ד ע״א שאסור לגנוב דעת הבריות ואפילו דעתו של עכו״ם וכ״ש הכא שהוא גניבת דעת לכולי עלמא אף לישראל, אלא 'דהוא גם גניבת דבר ממש דהא כשירצה לפרנסתו במשך הזמן להשכיר עצמו

- Roth (1989), op. cit. on YD 139.

- Joseph (1995)

- Tzedakah and Tzedek: Halachic & Ethical Financial Requirements Pertaining to Charitable Organizations by Daniel Feldman

- Baruch Litvin, The Sanctity of the Synagogue, 1962

- Tendler excerpt on Jlaw.com

- See Negiah, section entitled "Shaking Hands in Halacha," for a discussion regarding Rav Moshe's opinion on this topic, both with regard to initiating a handshake and with regard to returning a handshake (i. e., where the other party extends his/her hand first). For a translation of R' Moshe's three Teshuvos (responsa) on men shaking hands with women, see

- E. g., see Sinclair, Daniel. Jewish Biomedical Law 2004

- See RCA decision and, earlier, RCA Roundtable. (Statement by Saul Berman, Reuven Bulka, Daniel Landes and Jeffrey Woolf.) "Proposal on smoking" (unpublished) July 1991.

- Devarim Perek 31

- (November 18, 2015) "Chicago Orthodox Rabbi Found Guilty of Sexually Assaulting 15-year-old Boy", Haaretz

- Rich, Alan and Femmus, J. (February 17, 2016) "Jackie Mason: Bloomberg a Hypocrite!", The Jewish Voice

- Shalom C. Spira, "A Combination of Two Halakhically Kosher Prenuptial Agreements to Benefit the Jewish Wife," footnote 100

- For example, R' Yehudah haHasid's statement that certain verses of the Torah were written by an author other than Moses; and Nachmanides' statement that Abraham sinned by leaving Canaan and endangering his wife in Egypt (Darash Moshe Vayera 18:13: וטעות גדול ברמב"ן שכתב שאברהם חטא בזה, ותלמיד טועה טעה לדבר ח"ו סרה על אברהם)

Bibliography

- Eidensohn, Daniel (2000). יד משה: מפתח לכל ח׳ חלקים של שו״ת אגרות משה מאת משה פיינשטיין (in Hebrew). Jerusalem, Israel: D. Eidensohn. OCLC 51317225.

- Ellenson, David. "Two Responsa of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein." American Jewish Archives Journal, Volume LII, Nos. 1 and 2, Fall 2000–2001.

- Feinstein, Moshe; Moshe David Tendler (1996). Responsa of Rav Moshe Feinstein: translation and commentary. [translated and annotated] by Moshe Dovid Tendler. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 0-88125-444-4. LCCN 96011212. OCLC 34476198.

- Rabbi Shimon Finkelman, Rabbi Nosson Scherman. Reb Moshe: The Life and Ideals of HaGaon Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. Brooklyn, NY: ArtScroll Mesorah, 1986. ISBN 0-89906-480-9.

- Halperin, Mordechai (2006). "The Theological and Halakhic Legitimacy of Medical Therapy and Enhancement". In Noam Zohar (ed.). Quality of life in Jewish bioethics. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-1446-8. LCCN 2005029443. OCLC 62078279.

- Joseph, Norma Baumel (1995). Separate Spheres: Women in the Responsa of Rabbi Moses Feinstein (PhD thesis). Concordia University.

- "Rav Moshe Feinstein". Great Leaders of our People. Orthodox Union. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- _________. "Jewish education for women: Rabbi Moshe Feinstein's map of America." American Jewish history, 1995

- Rackman, Emanuel. "Halachic progress: Rabbi Moshe Feinstein's Igrot Moshe on Even ha-Ezer" in Judaism 12 (1964), 365–373

- Robinson, Ira. "Because of our many sins: The contemporary Jewish world as reflected in the responsa of Moses Feinstein" 2001

- Rosner, Fred. "Rabbi Moshe Feinstein's Influence on Medical Halacha" Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society. No. XX, 1990

- __________. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein on the treatment of the terminally ill." Judaism. Spring 37(2):188–98. 1988

- Rabbi Mordecai Tendler, interview with grandson of Rabbi Feinstein and shamash for 18 years.

- Warshofsky, Mark E. "Responsa and the Art of Writing: Three Examples from the Teshuvot of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein," in An American Rabbinate: A Festschrift for Walter Jacob Pittsburgh, Rodef Shalom Press, 2001 (Download in PDF format)

External links

- Biography of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein

- “HaRav Moshe Feinstein: In honor of his 15th yahrtzeit, 13th Adar” – A retrospective of Rav Moshe Feinstein's life, with recollections on his character as a person.

- Most volumes of Igros Moshe are available for free at hebrewbooks.org. A detailed listing with links to all freely available sections appears at Mi Yodeya: Quick-Reference List of the Section-Contents of Igros Moshe.