Loneliness

Loneliness is an unpleasant emotional response to perceived isolation. Loneliness is also described as social pain—a psychological mechanism which motivates individuals to seek social connections. It is often associated with an unwanted lack of connection and intimacy. Loneliness overlaps and yet is distinct from solitude. Solitude is simply the state of being apart from others, not everyone who experiences solitude feels lonely. As a subjective emotion, loneliness can be felt even when surrounded by other people; one who feels lonely, is lonely. The causes of loneliness are varied. They include social, mental, emotional, and environmental factors.

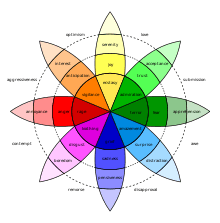

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

|

Research has shown that loneliness is found throughout society, including among people in marriages along with other strong relationships, and those with successful careers. Most people experience loneliness at some points in their lives, and some feel it very often. As a short term emotion, loneliness can be beneficial; it encourages the strengthening of relationships. Chronic loneliness on the other hand is widely considered harmful, with numerous reviews and meta-studies concluding it is a significant risk factor for poor mental and physical health outcomes.

Loneliness has long been a theme in literature, going back to the Epic of Gilgamesh. Yet academic study of loneliness was sparse until the late twentieth century. In the 21st century, loneliness has been increasingly recognised as a social problem, with both NGOs and governmental actors seeking to tackle it.

Common causes

People can experience loneliness for many reasons, and many life events may cause it, such as a lack of friendship relations during childhood and adolescence, or the physical absence of meaningful people around a person. At the same time, loneliness may be a symptom of another social or psychological problem, such as chronic depression.

Many people experience loneliness for the first time when they are left alone as infants. It is also a very common, though normally temporary, consequence of a breakup, divorce, or loss of any important long-term relationship. In these cases, it may stem both from the loss of a specific person and from the withdrawal from social circles caused by the event or the associated sadness.

The loss of a significant person in one's life will typically initiate a grief response; in this situation, one might feel lonely, even while in the company of others. Loneliness may also occur after the birth of a child (often expressed in postpartum depression), after marriage, or following any other socially disruptive event, such as moving from one's home town into an unfamiliar community, leading to homesickness. Loneliness can occur within unstable marriages or other close relationships of a similar nature, in which feelings present may include anger or resentment, or in which the feeling of love cannot be given or received. Loneliness may represent a dysfunction of communication, and can also result from places with low population densities in which there are comparatively few people to interact with. Loneliness can also be seen as a social phenomenon, capable of spreading like a disease. When one person in a group begins to feel lonely, this feeling can spread to others, increasing everybody's risk for feelings of loneliness.[1] People can feel lonely even when they are surrounded by other people.[2]

Whether a correlation exists between Internet usage and loneliness is a subject of controversy, with some findings showing that Internet users are lonelier[3] and others showing that lonely people who use the Internet to keep in touch with loved ones (especially seniors) report less loneliness, but that those trying to make friends online became lonelier.[4] On the other hand, studies in 2002 and 2010 found that "Internet use was found to decrease loneliness and depression significantly, while perceived social support and self-esteem increased significantly"[5] and that the Internet "has an enabling and empowering role in people's lives, by increasing their sense of freedom and control, which has a positive impact on well-being or happiness."[6]

A twin study found evidence that genetics account for approximately half of the measurable differences in loneliness among adults, which was similar to the heritability estimates found previously in children. These genes operate in a similar manner in males and females. The study found no common environmental contributions to adult loneliness.[7]

The one apparently unequivocal finding of correlation is that long driving commutes correlate with dramatically higher reported feelings of loneliness (as well as other negative health impacts).[8][9]

Typology

Two principal types of loneliness are social and emotional loneliness. This delineation was made in 1973 by Robert S. Weiss, in his seminal work: Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation [10] Based on Weiss's view that "both types of loneliness have to be examined independently, because the satisfaction for the need of emotional loneliness cannot act as a counterbalance for social loneliness, and vice versa", people working to treat or better understand loneliness have tended to treat these two types of loneliness separately, though this is far from always the case.[11][12]

Social loneliness

Social loneliness is the loneliness people experience because of the lack of a wider social network. They may not feel they are members of a community, or that they have friends or allies whom they can rely on in times of distress.[10][12]

Emotional loneliness

Emotional loneliness results from the lack of deep, nurturing relationships with other people. Weiss tied his concept of emotional loneliness to attachment theory. People have a need for deep attachments, which can sometimes be fulfilled by close friends, but much more often by close family members such as parents, and later in life by romantic partners. In 1997, Enrico DiTommaso and Barry Spinner separated emotional loneliness into Romantic and Family loneliness.[12] [13] A 2019 study found that emotional loneliness significantly increased the likelihood of death for older adults living alone (whereas there was no increase in mortality found with social loneliness). [13]

Family loneliness

Family loneliness results when individuals feel they lack close ties with family members. A 2010 study of 1,009 students found that only family loneliness was associated with increased frequency of self harm, not romantic or social loneliness.[14][12]

Romantic loneliness

Romantic loneliness can be experienced by adolescents and adults who lack a close bond with a romantic partner. Psychologists have asserted that the formation of a committed romantic relationship is a critical development task for young adults. Though it is also one that many are delaying into their late 20s or beyond. People in romantic relationships tend to report less loneliness than single people, providing their relationship provides them with emotional intimacy. People in unstable or emotionally cold romantic partnerships can still feel romantic loneliness.[15][12]

Other

Several other typologies and types of loneliness exist. Further types of loneliness include existential loneliness, cosmic loneliness - feeling alone in a hostile universe, and cultural loneliness - typically found among immigrants who miss their home culture. [16] These types are less well studied than the three fold separation into social, romantic and family loneliness, yet can be valuable in understanding the experience of certain sub groups suffering from loneliness.[17] [12]

Demarcation

Feeling lonely vs. being socially isolated

There is a clear distinction between feeling lonely and being socially isolated (for example, a loner). In particular, one way of thinking about loneliness is as a discrepancy between one's necessary and achieved levels of social interaction,[18] while solitude is simply the lack of contact with people. Loneliness is therefore a subjective experience; if a person thinks they are lonely, then they are lonely. People can be lonely while in solitude, or in the middle of a crowd. What makes a person lonely is the fact that they need more social interaction or a certain type of social interaction that is not currently available. A person can be in the middle of a party and feel lonely due to not talking to enough people. Conversely, one can be alone and not feel lonely; even though there is no one around that person is not lonely because there is no desire for social interaction. There have also been suggestions that each person has their own optimal level of social interaction. If a person gets too little or too much social interaction, this could lead to feelings of loneliness or over-stimulation.[19]

Solitude can have positive effects on individuals. One study found that, although time spent alone tended to depress a person's mood and increase feelings of loneliness, it also helped to improve their cognitive state, such as improving concentration. Furthermore, once the alone time was over, people's moods tended to increase significantly.[20] Solitude is also associated with other positive growth experiences, religious experiences, and identity building such as solitary quests used in rites of passages for adolescents.[21]

Transient vs. chronic loneliness

Another important typology of loneliness focuses on the time perspective.[22] In this respect, loneliness can be viewed as either transient or chronic.

Transient loneliness is temporary in nature; generally it is easily relieved. Chronic loneliness is more permanent and not easily relieved.[23] For example, when a person is sick and cannot socialize with friends, this would be a case of transient loneliness. Once the person got better it would be easy for them to alleviate their loneliness. A person with long term feelings of loneliness regardless of if they are at a family gathering or with friends is experiencing chronic loneliness.

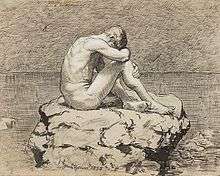

Loneliness as a human condition

The existentialist school of thought views loneliness as the essence of being human. Each human being comes into the world alone, travels through life as a separate person, and ultimately dies alone. Coping with this, accepting it, and learning how to direct our own lives with some degree of grace and satisfaction is the human condition.[24]

Some philosophers, such as Sartre, believe in an epistemic loneliness in which loneliness is a fundamental part of the human condition because of the paradox between people's consciousness desiring meaning in life and the isolation and nothingness of the universe.[25] Conversely, other existentialist thinkers argue that human beings might be said to actively engage each other and the universe as they communicate and create, and loneliness is merely the feeling of being cut off from this process.

In his 2019 text, Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence, Darius Bost draws from Heather Love's theorization of loneliness[26] to delineate the ways in which loneliness structures black gay feeling and literary, cultural productions. Bost limns, “As a form of negative affect, loneliness shores up the alienation, isolation, and pathologization of black gay men during the 1980s and early 1990s. But loneliness is also a form of bodily desire, a yearning for an attachment to the social and for a future beyond the forces that create someone’s alienation and isolation."[27]

Frequency

Thousands of studies and surveys have been undertaken to assess the prevalence of loneliness. Yet it remains challenging for scientists to make accurate generalisations and comparisons. Reasons for this include various loneliness measurement scales being used by different studies, differences in how even the same scale is implemented from study to study, and as cultural variations across time and space may impact how people report the largely subjective phenomena of loneliness.[28][29]

One consistent finding has been that loneliness is not evenly distributed across a nation's population. It tends to be concentrated among vulnerable sub groups; for example the poor, the unemployed, and immigrants. Some of the most severe loneliness tends to be found among international students from countries in Asia with a collective culture, when they come to study in countries with a more individualist culture, such as Australia.[12] In New Zealand, the fourteen surveyed groups with the highest prevalence of loneliness most/all of the time in descending order are: disabled, recent migrants, low income households, unemployed, single parents, rural (rest of South Island), seniors aged 75+, not in the labour force, youth aged 15–24, no qualifications, not housing owner-occupier, not in a family nucleus, Māori, and low personal income.[30]

Another of the more consistent findings is that women tend to report feeling lonely more often than men. Though exceptions have been found by some of the studies focusing on students, where male students have reported higher loneliness, especially emotional loneliness, compared to females.[12][31]

Studies have also tended to find that older people are more likely to report loneliness, though again there are exceptions, such as the Community Life Survey, 2016 to 2017, by the UK's Office for National Statistics, which found that young adults in England aged 16 to 24 reported feeling lonely more often than those in older age groups.[32][12][29]

While cross cultural comparisons are difficult to interpret with high confidence, the English speaking countries have generally been found to have the highest rates of loneliness, followed by some of the southern European countries and Japan, with the rest of the world tending to be less lonely. For example, surveys have tended to find between 20-28% of the population in the US, Canada, Australia and Great Britain report feeling lonely frequently, compared with about 3-10% for China, Japan and South Africa .[33]

In the 21st century, loneliness has been widely reported as an increasing worldwide problem. The issue has been labelled as a growing epidemic by media figures, academics, and by many political officials, most prominently Vivek Murthy, former Surgeon General of the United States. A 2010 systematic review and meta analyses noted that the "modern way of life in industrialized countries" is greatly reducing the quality of social relationships, partly due to people no longer living in close proximity with their extended families. The review notes that from 1990 to 2010, the number of Americans reporting no close confidants has tripled.[34] Worldwide though there is little historical data to conclusively demonstrate an increase in loneliness. Several reviews have found no clear evidence of an increase in loneliness even in the USA. Professors such as Claude S. Fischer and Eric Klinenberg have opined that while there is no loneliness epidemic, loneliness is indeed a serious issue, having a severe health impact on millions of people.[35][36][37]

Effects

Transient

While unpleasant, temporary feelings of loneliness are sometimes experienced by almost everyone, and are not thought to cause long term harm. Early 20th century work sometimes treated loneliness as a wholly negative phenomena. Yet transient loneliness is now generally considered beneficial. The capacity to feel it may have been evolutionarily selcted for, a healthy aversive emotion that motivates individuals to strengthen social connections. [38] Transient loneliness is sometimes compared to short term hunger, which is unpleasant but ultimately useful as it motivates us to eat.[39] [12] [40]

Chronic

Long term loneliness is widely considered a close to entirely harmful condition. Whereas transient loneliness typically motivates us to improve relationships with others, chronic loneliness can have the opposite effect. This is as long term social isolation can cause hypervigilance. While enhanced vigilance may have been evolutionary adaptive for individuals who went long periods without others watching their backs, it can lead to excessive cynicism and suspicion of other people, which in turn can be detrimental to interpersonal relationships . So without intervention, chronic loneliness can be self-reinforcing. [39] [12] [40]

Benefits

Much has been written about the benefits of being alone, yet often, even when authors use the word "loneliness", they are referring to what could be more precisely described as voluntary solitude. Yet some assert that even long term involuntary loneliness can have beneficial effects. [41] [42]

Chronic loneliness is often seen as a purely negative phenomena from the lens of social and medical science. Yet in spiritual and artistic traditions, it has been viewed as having mixed effects. Though even within these traditions, there can be warnings not to intentionally seek out chronic loneliness or other afflictions - just advise that if one falls into them, there can be benefits. In western arts, there is a long belief that psychological hardship, including loneliness, can be a source of creativity.[42] In spiritual traditions, perhaps the most obvious benefit of loneliness is that in can increase the desire for a union with the divine. More esoterically, the psychic wound opened up by loneliness or other afflictions has been said, e.g. by Simone Weil, to open up space for God to manifest within the soul. In Christianity, spiritual dryness has been seen as advantageous as part of the "dark night of the soul", an ordeal that while painful, can result in spiritual transformation. From a secular perspective, while the vast majority of empirical studies focus on the negative effects of long term loneliness, a few studies have found there can also be benefits, such as enhanced perceptiveness of social situations. [42] [43]

Physical health

Chronic loneliness can be a serious, life-threatening health condition. It has been found to be associated with an increased risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease.[44] Loneliness shows an increased incidence of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity.[45]

Loneliness is shown to increase the concentration of cortisol levels in the body and weaken the effects dopamine, the hormone that makes you enjoy things.[45] Prolonged, high cortisol levels can cause anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, sleep problems, and weight gain.[46]

″Loneliness has been associated with impaired cellular immunity as reflected in lower natural killer (NK) cell activity and higher antibody titers to the Epstein Barr Virus and human herpes viruses".[45] Because of impaired cellular immunity, loneliness among young adults shows vaccines, like the flu vaccine, to be less effective.[45] Data from studies on loneliness and HIV positive men suggests loneliness increases disease progression.[45]

Death

A 2010 systematic review and meta- analyses found a significant association between loneliness and increased mortality. People with good social relationships were found to have a 50% greater chance of survival compared to lonely people ( odds ratio = 1.5). In other words, chronic loneliness seems to be a risk factor for death comparable to smoking, and greater than obesity or lack of exercise.[34] A 2017 overview of systematic reviews found other meta-studies with similar findings. However, clear causative links between loneliness and early death have not been firmly established.[47]

Mental health

Loneliness has been linked with depression, and is thus a risk factor for suicide.[48] Émile Durkheim has described loneliness, specifically the inability or unwillingness to live for others, i.e. for friendships or altruistic ideas, as the main reason for what he called egoistic suicide.[49] In adults, loneliness is a major precipitant of depression and alcoholism.[50] People who are socially isolated may report poor sleep quality, and thus have diminished restorative processes.[51] Loneliness has also been linked with a schizoid character type in which one may see the world differently and experience social alienation, described as the self in exile.[52]

While the long term effects of extended periods of loneliness are little understood, it has been noted that people who are isolated or experience loneliness for a long period of time fall into a “ontological crisis” or “ontological insecurity,” where they are not sure if they or their surroundings exist, and if they do, exactly who or what they are, creating torment, suffering, and despair to the point of palpability within the thoughts of the person.[53][54]

In children, a lack of social connections is directly linked to several forms of antisocial and self-destructive behavior, most notably hostile and delinquent behavior. In both children and adults, loneliness often has a negative impact on learning and memory. Its disruption of sleep patterns can have a significant impact on the ability to function in everyday life.[48]

Research from a large-scale study published in the journal Psychological Medicine, showed that "lonely millennials are more likely to have mental health problems, be out of work and feel pessimistic about their ability to succeed in life than their peers who feel connected to others, regardless of gender or wealth.”[55][56]

In 2004, the United States Department of Justice published a study indicating that loneliness increases suicide rates profoundly among juveniles, with 62% of all suicides that occurred within juvenile facilities being among those who either were, at the time of the suicide, in solitary confinement or among those with a history of being housed thereof.[53]

Pain, depression, and fatigue function as a symptom cluster and thus may share common risk factors. Two longitudinal studies with different populations demonstrated that loneliness was a risk factor for the development of the pain, depression, and fatigue symptom cluster over time. These data also highlight the health risks of loneliness; pain, depression, and fatigue often accompany serious illness and place people at risk for poor health and mortality.[57]

Suicide

Suicide, suicidal thoughts, attempts at suicide as a result of loneliness happen. In an article written for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevent Dr. Jeremy Noble writes, “You don’t have to be a doctor to recognize the connection between loneliness and suicide.” [58] As feelings of loneliness intensify so do thoughts of suicide and attempts at suicide [59] The loneliness that triggers suicidal tendencies impacts all facets of society.

The Samaritans, a nonprofit charity in England, who work with people going through crisis says there is a definite correlation between feelings of loneliness and suicide for juveniles and those in their young adult years.[59] The Office of National Statistics, in England, found one of the top ten reasons young people have suicidal idealizations and attempt suicide is because they are lonely.[60] College students, lonely, away from home, living in new unfamiliar surroundings, away from friends feel isolated and without proper coping skills will turn to suicide as a way to fix the pain of loneliness.[60] A common theme, among children and young adults dealing with feelings of loneliness is they didn't know help was available, or where to get help. Loneliness, to them, is a source of shame.[60]

Older people, specifically senior citizens also struggle with feelings of severe loneliness which lead them to considering or acting on thoughts of suicide or self harm. Retirement, poor health, loss of a significant other or other family or friends, all contribute to loneliness. The isolation leads to loneliness; the loneliness leads to self harm or suicidal thoughts or actions. Suicides caused by loneliness in seniors can sometime be difficult to identify. Often they don't have anyone to disclose their feelings of loneliness and the despair it brings. They will stop eating, alter the doses of medications they should take, choose not to treat an illness leading as a way to help expedite death so they don't have to deal with feeling lonely.

Cultural influences can also cause loneliness leading to suicidal thoughts or actions. For example, Hispanic and Japanese cultures value interdependence. When a person from one of these cultures feels removed or feels they can't sustain relationships in their families or society they start to have negative behaviours which include negative thoughts or acting self-destructively. Other cultures, such as Caucasian have a culture that is more independent, culturally.While the cause of loneliness in a person may stem from different circumstances or cultural norms the impact lead to the same results, a desire to end life.

Physiological mechanisms link to poor health

There are a number of potential physiological mechanisms linking loneliness to poor health outcomes. In 2005, results from the American Framingham Heart Study demonstrated that lonely men had raised levels of Interleukin 6 (IL-6), a blood chemical linked to heart disease. A 2006 study conducted by the Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience at the University of Chicago found loneliness can add thirty points to a blood pressure reading for adults over the age of fifty. Another finding, from a survey conducted by John Cacioppo from the University of Chicago, is that doctors report providing better medical care to patients who have a strong network of family and friends than they do to patients who are alone. Cacioppo states that loneliness impairs cognition and willpower, alters DNA transcription in immune cells, and leads over time to high blood pressure.[61] Lonelier people are more likely to show evidence of viral reactivation than less lonely people.[62] Lonelier people also have stronger inflammatory responses to acute stress compared with less lonely people; inflammation is a well known risk factor for age-related diseases.[63]

When someone feels left out of a situation, they feel excluded and one possible side effect is for their body temperature to decrease. When people feel excluded blood vessels at the periphery of the body may narrow, preserving core body heat. This class protective mechanism is known as vasoconstriction.[64]

Relief

The reduction of loneliness in oneself and others has long been a motive for human activity and social organisation. For some commentators, such as professor Ben Lazare Mijuskovic, ever since the dawn of civilization, it has been the single strongest motivator for human activity after essential physical needs are satisfied. Loneliness is the first negative condition identified in the Holy Bible, with the Book of Genesis showing God creating a companion for man to relief loneliness. Nevertheless, there is relatively little direct record of explicit loneliness relief efforts prior to the 20th century. Some commentators including professor Rubin Gotesky have argued the sense of aloneness was rarely felt until older communal ways of living began to be disrupted by the enlightenment. [17][16][42]

Starting in the 1900s, and especially in the 21st century, efforts explicitly aiming to alleviate loneliness became much more common. Loneliness reduction efforts occur across multiple disciplines, often by actors for whom loneliness relief is not their primary concern. For example, civic planning, the design of new housing developments, and university administration. Across the world, many departments and even entire NGO's dedicated to loneliness relief have been established. For example in the UK, the Campaign to End Loneliness. [39][37] [42]

Medical treatment

Therapy is a common way of treating loneliness; for individuals whose loneliness is caused by factors that respond well to medical intervention, it is often successful. Short-term therapy, the most common form for lonely or depressed patients, typically occurs over a period of ten to twenty weeks. During therapy, emphasis is put on understanding the cause of the problem, reversing the negative thoughts, feelings, and attitudes resulting from the problem, and exploring ways to help the patient feel connected. Some doctors also recommend group therapy as a means to connect with other sufferers and establish a support system.[65] Doctors also frequently prescribe anti-depressants to patients as a stand-alone treatment, or in conjunction with therapy. It may take several attempts before a suitable anti-depressant medication is found.[66]

Alternative approaches to treating depression are suggested by many doctors. These treatments include exercise, dieting, hypnosis, electro-shock therapy, acupuncture, and herbs, amongst others. Many patients find that participating in these activities fully or partially alleviates symptoms related to depression.[67]

Another treatment for both loneliness and depression is pet therapy, or animal-assisted therapy, as it is more formally known. Studies and surveys, as well as anecdotal evidence provided by volunteer and community organizations, indicate that the presence of animal companions such as dogs, cats, rabbits, and guinea pigs can ease feelings of depression and loneliness among some sufferers. Beyond the companionship the animal itself provides there may also be increased opportunities for socializing with other pet owners. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention there are a number of other health benefits associated with pet ownership, including lowered blood pressure and decreased levels of cholesterol and triglycerides.[68]

Nostalgia has also been found to have a restorative effect, counteracting loneliness by increasing perceived social support.[69] Studies have found an association with religion and the reduction of loneliness, especially among the elderly. The studies sometimes include caveats, such as that religions with strong behavioural prescriptions can have isolating effects. [70] [71]

A meta-study compared the effectiveness of four interventions: improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing opportunities for social interaction, addressing abnormal social cognition (faulty thoughts and patterns of thoughts). The results of the study indicated that all interventions were effective in reducing loneliness, possibly with the exception of social skill training. Results of the meta-analysis suggest that correcting maladaptive social cognition offers the best chance of reducing loneliness.[39]

History

Loneliness has been appeared in literature throughout the ages, as far back as Epic of Gilgamesh. [17] [16] Yet according to Fay Bound Alberti, it was only around the year 1800 that the word began to widely denote a negative condition. Earlier dictionary definitions of loneliness equated it with solitude – a state that was often seen as positive, unless taken to excess. From about 1800, the word loneliness began to acquire its modern definition as a painful subjective condition. This may due to economic and social changes arising out the Enlightenment. Such as alienation and increased interpersonal competition, along with a reduction in the number of people that would enjoy close and enduring connections with the people living in close proximity with them, as may for example have been the case for modernising pastoral villages.[72] [42] Despite growing awareness of the problem of loneliness, widespread social recognition of the problem was limited, and scientific study remained sparse, until the last quarter of the twentieth century. One of the earliest studies of loneliness was published by Joseph Harold Sheldon in 1948.[73] The 1950 book The Lonely Crowd helped further raise the profile of loneliness among academics. For the general public, awareness was raised by the 1966 Beatles song Eleanor Rigby.[42]

According to Eugene Garfield, it was Robert S. Weiss who brought the attention of scientists to the topic of loneliness, with his 1973 publication of Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. [74] Prior to Weiss's publication, what few studies of loneliness existed were mostly focussed on old people. Following Weis's work, and especially after the 1978 publication of the UCLA Loneliness Scale, scientific interest in the topic has broadened and deepened considerably, with tens of thousands of academic studies having been carried to investigate loneliness just among students, with many more focussed on other sub groups, and on whole populations.[75][12][42] [43]

Concern among the general public over loneliness increased in the decades since Eleanor Rigby's release; by 2018 government backed anti-loneliness campaigns had been launched in countries including the UK, Denmark and Australia.[37]

See also

- Adam's Song

- Autophobia

- Eleanor Rigby

- Individualism

- Interpersonal relationship

- Loner

- Pit of despair (animal experiments on isolation)

- Schizoid personality disorder

- Solitude

- Shyness

- Social anxiety

- Social anxiety disorder

- Social isolation

Notes and references

- Parker, Pope (1 December 2009). "Why loneliness can be contagious". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Feeling Alone Together: How Loneliness Spreads". Time.com. 1 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Hughes, Carole (1999). The relationship of use of the Internet and loneliness among college students (PhD Thesis). Boston College. OCLC 313894784.

- Sum, Shima; Mathews, R. Mark; Hughes, Ian; Campbell, Andrew (2008). "Internet Use and Loneliness in Older Adults". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 11 (2): 208–11. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0010. PMID 18422415.

- Shaw, Lindsay H.; Gant, Larry M. (2002). "In Defense of the Internet: The Relationship between Internet Communication and Depression, Loneliness, Self-Esteem, and Perceived Social Support". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 5 (2): 157–71. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.563.2946. doi:10.1089/109493102753770552. PMID 12025883.

- "Is the Internet the Secret to Happiness?". Time. 14 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Boomsma, Dorret I.; Willemsen, Gonneke; Dolan, Conor V.; Hawkley, Louise C.; Cacioppo, John T. (2005). "Genetic and Environmental Contributions to Loneliness in Adults: The Netherlands Twin Register Study". Behavior Genetics. 35 (6): 745–52. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.498. doi:10.1007/s10519-005-6040-8. PMID 16273322.

- Lowrey, Annie (26 May 2011). "Long commutes cause obesity, neck pain, loneliness, divorce, stress, and insomnia". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Paumgarten, Nick (9 April 2007). "There and Back Again". newyorker.com. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Weiss, R.S. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973.

- Loneliness at Universities: Determinants of Emotional and Social Loneliness among Students , Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15(9), 1865; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091865 , by Katharina Diehl , Charlotte Jansen , Kamila Ishchanova and Jennifer Hilger-Kolb

- Ami Sha'ked ,Ami Rokach, eds. (2015). "3,4, 9,12, 16". Addressing Loneliness: Coping, Prevention and Clinical Interventions. Psychology Press. ISBN 1138026212.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link)

- O'Súilleabháin, Páraic S.; Gallagher, Stephen; Steptoe, Andrew (2019). "Loneliness, Living Alone, and All-Cause Mortality: The Role of Emotional and Social Loneliness in the Elderly During 19 Years of Follow-Up". Psychosomatic Medicine. 81 (6): 521–526. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000710. hdl:10344/8038. ISSN 0033-3174. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Different sources of loneliness are associated with different forms of psychopathology in adolescence , Journal of Research in Personality Volume 45, Issue 2, April 2011, Pages 233-237 , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.12.005 ; by Mathias Lasgaard ,Luc Goossens, Rikke HolmBramsen, Tea Trillingsgaard and Ask Elklita

- Lesch, Elmien; Casper, Rozanne; van der Watt, Alberta S. J. (2016). "Romantic relationships and loneliness in a group of South African postgraduate students". South African Review of Sociology. 47 (4): 22–39. doi:10.1080/21528586.2016.1182442. ISSN 2152-8586.

- John G. McGraw (2010). Intimacy and Isolation. Rodopi. pp. 107-149. 417-420. ISBN 9042031395.

- Ben Lazare Mijuskovic (2012). Loneliness in Philosophy, Psychology, and Literature. iUniverse. pp. 60–69. ISBN 978-1-4697-8934-7.

- Peplau, L.A.; Perlman, D. (1982). "Perspectives on loneliness". In Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel (eds.). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- Suedfeld, P. (1989). "Past the reflection and through the looking-glass: Extending loneliness research". In Hojat, M.; Crandall, R. (eds.). Loneliness: Theory, research and applications. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications. pp. 51–6.

- Larson, R.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Graef, R. (1982). "Time alone in daily experience: Loneliness or renewal?". In Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel (eds.). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 41–53. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- Suedfeld, P. (1982). "Aloneness as a healing experience". In Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel (eds.). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 54–67. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- de Jong-Gierveld, J.; Raadschelders, J. (1982). "Types of loneliness". In Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel (eds.). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 105–19. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- Duck, S. (1992). Human relations (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- An Existential View of Loneliness Archived 27 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine – Carter, Michele; excerpt from Abiding Loneliness: An Existential Perspective, Park Ridge Center, September 2000

- Tomšik, Robert (2015). Relationship of loneliness and meaning of life among adolescents. In Current Trends in Educational Science and Practice VIII : International Proceedings of Scientific Studies. Nitra: UKF. pp. 66–7. ISBN 978-80-558-0813-0.

- Love, H. K. (1 January 2001). ""SPOILED IDENTITY": Stephen Gordon's Loneliness and the Difficulties of Queer History". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 7 (4): 487–519. doi:10.1215/10642684-7-4-487. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Bost, Darius (2019). Evidence of Being. University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226589961.001.0001. ISBN 9780226589824.

- Professor Christina Victor, Professor Louise Mansfield, Professor Tess Kay, Professor Norma Daykin, Mr Jack Lane, Ms Lily Grigsby Duffy, Professor Alan Tomlinson, Professor Catherine Meads (October 2018). "An overview of reviews: the effectiveness of interventions to address loneliness at all stages of the life-course" (PDF). whatworkswellbeing.org. Retrieved 1 March 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Andrew Stickley, Ai Koyanagi, Bayard Roberts, Erica Richardson, Pamela Abbott, Sergei Tumanov, Martin McKee (2013). "Loneliness: Its Correlates and Association with Health Behaviours and Outcomes in Nine Countries of the Former Soviet Union". PLOS ONE. 8: e67978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067978.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Comber, Cathy. "Ms". www.loneliness.org.nz. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Diehl K, Jansen C, Ishchanova K, Hilger-Kolb J. Loneliness at Universities: Determinants of Emotional and Social Loneliness among Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Aug 29;15(9):1865. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091865. PMID 30158447; PMCID: PMC6163695.

- Loneliness – What characteristics and circumstances are associated with feeling lonely? Archived 25 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Analysis of characteristics and circumstances associated with loneliness in England using the Community Life Survey, 2016 to 2017. Published by the Office for National Statistics. Published 10 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Gabrielle Denman (18 November 2019). "All the lonely people – the epidemic of loneliness and its consequences". Social Science Works. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Julianne Holt-Lunstad , Timothy B. Smith , J. Bradley Layton (2010). "Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review". PLOS Medicine. 7: e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

-

Eric Klinenberg (9 February 2018). "Is Loneliness a Health Epidemic?". New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

But is loneliness, as many political officials and pundits are warning, a growing “health epidemic”?”

- "All the Lonely Americans?". United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- "Loneliness is a serious public-health problem". The Economist. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Sometimes called the "reaffiliation motive", e.g. see Loneliness across the life span

- Masi, C. M.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hawkley, L. C.; Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). "A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 15 (3): 219–66. doi:10.1177/1088868310377394. PMC 3865701. PMID 20716644.

- Carin Rubenstein, Phillip R. Shaver (1982). In search of intimacy. Delacorte Press. pp. 3, 152, 172 260, passim. ISBN 0385284802.

- Brent Crane (March 2017). "The Virtues of Isolation". The Atlantic. Retrieved 5 April 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fay Bound Alberti (2019). A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–40, 61–83. ISBN 9780198811343.

- Cody Delistraty (July 2016). "Only the lonely". aeon. Retrieved 5 April 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Loneliness and Isolation: Modern Health Risks". The Pfizer Journal. IV (4). 2000. Archived from the original on 28 January 2006.

- Cacioppo, J.; Hawkley, L. (2010). "Loneliness Matters: A Theorectical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 40 (2): 218–227. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. PMC 3874845. PMID 20652462.

- "Chronic stress puts your health at risk". Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- N. Leigh-Hunta, D. Bagguleyb, K. Bashb, V. Turnerb, S. Turnbullb,N. Valtortac, W. Caan (2017). "An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness" (PDF). PLOS ONE.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- The Dangers of Loneliness – Marano, Hara Estroff; Psychology Today Thursday 21 August 2003

- Shelkova, Polina (2010). "Loneliness". Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Marano, Hara. "The Dangers of Loneliness". Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Hawkley, Louise C; Cacioppo, John T (2003). "Loneliness and pathways to disease". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 17 (1): 98–105. doi:10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9. PMID 12615193.

- Masterson, James F.; Klein, Ralph (1995). Disorders of the Self: Secret Pure Schizoid Cluster Disorder. pp. 25–7.

Klein was Clinical Director of the Masterson Institute and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York

- Mark Berman (9 June 2015). "Kalief Browder and what we do and don't know about solitary confinement in the U.S." The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "Testimony of Professor Craig Haney; Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Human Rights Hearing on Solitary Confinement" (PDF). United States Senate. 19 June 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- Loneliness linked to major life setbacks for millennials, study says Archived 25 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Author – Nicola Davis. Published 24 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study Archived 25 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Psychological Medicine. Authors – Timothy Matthews (a1), Andrea Danese (a1) (a2), Avshalom Caspi (a1) (a3), Helen L. Fisher (a1), Sidra Goldman-Mellor (a4), Agnieszka Kepa (a1), Terrie E. Moffitt (a1) (a3), Candice L. Odgers (a5) (a6) and Louise Arseneault (a1). Published online on 24 April 2018. Published by Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Jaremka, L.M.; Andridge, R.R.; Fagundes, C.P.; Alfano, C.M.; Povoski, S.P.; Lipari, A.M.; Agnese, D.M.; Arnold, M.W.; Farrar, W.B.; Yee, L.D. Carson III; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Martin Jr, E.W.; Schmidt, C.R.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. (2014). "Pain, depression, and fatigue: Loneliness as a longitudinal risk factor". Health Psychology. 38: 1310–1317.

- Nobel, Jeremy; MD; MPH; Founder; President; Art, Foundation for; Healing (25 September 2018). "Forging Connection Against Loneliness". AFSP. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Stravynski, Ariel; Boyer, Richard (2001). "Loneliness in Relation to Suicide Ideation and Parasuicide: A Population-Wide Study". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 31 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1521/suli.31.1.32.21312. ISSN 1943-278X.

- "Young people and suicide". Samaritans. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Cacioppo, John; Patrick, William, Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection, New York : W.W. Norton & Co., 2008. ISBN 978-0-393-06170-3. Science of Loneliness.com Archived 1 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Jaremka, Lisa M.; Fagundes, Christopher P.; Glaser, Ronald; Bennett, Jeanette M.; Malarkey, William B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K. (2013). "Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: Understanding the role of immune dysregulation". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 38 (8): 1310–7. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.016. PMC 3633610. PMID 23273678.

- Jaremka, Lisa M.; Fagundes, Christopher P.; Peng, Juan; Bennett, Jeanette M.; Glaser, Ronald; Malarkey, William B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K. (2013). "Loneliness Promotes Inflammation During Acute Stress". Psychological Science. 24 (7): 1089–97. doi:10.1177/0956797612464059. PMC 3825089. PMID 23630220.

- Ijzerman, Hans. "Getting the cold shoulder". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- "Psychotherapy". Depression.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- "The Truth About Antidepressants". WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- "Alternative treatments for depression". WebMD. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Health Benefits of Pets Archived 15 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine (from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Zhou, Xinyue; Sedikides, Constantine; Wildschut, Tim; Gao, Ding-Guo (2008). "Counteracting Loneliness: On the Restorative Function of Nostalgia". Psychological Science. 19 (10): 1023–9. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02194.x. PMID 19000213.

- Doman, LCH and Roux,A (2010). "The causes of loneliness and the factors that contribute towards it - A literature review". Tydskrift vir Geesteswetenskappe. 50: 216–228.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Johnson, D. P.; Mullins, L. C. (1989). "Religiosity and Loneliness Among the Elderly". Journal of Applied Gerontology. 8: 110–31. doi:10.1177/073346488900800109.

- Pankaj Mishra (2017). Age of Anger. Penguin Books. pp. 75, 172, 187–188, 269–270, 336–338. ISBN 9780141984087.

- Sheldon, J.H. (1948). "The Social Medicine of Old Age. Report of an Enquiry in Wolverhampton". Journal of Gerontology. 3 (4): 306–308.

- Eugene Garfield (3 February 1986). "The Loneliness Researcher Is Not so Lonely Anymore" (PDF). Essays of an information scientist. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Anderson, Keith A. (2019). "The Virtual Care Farm: A Preliminary Evaluation of an Innovative Approach to Addressing Loneliness and Building Community through Nature and Technology". Activities, Adaptation & Aging. 43 (4): 334–344. doi:10.1080/01924788.2019.1581024.

External links