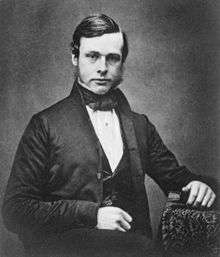

Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, OM, PC, PRS (5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912),[1] known between 1883 and 1897 as Sir Joseph Lister, Bt., was a British surgeon and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery.

Joseph Lister | |

|---|---|

Lister in 1902 | |

| President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1895–1900 | |

| Preceded by | The Lord Kelvin |

| Succeeded by | Sir William Huggins |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 April 1827 Upton House, West Ham, England |

| Died | 10 February 1912 (aged 84) Walmer, Kent, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse(s) | Agnes Lister (nee Syme) |

| Signature | |

| Alma mater | University College, London |

| Known for | Surgical sterile techniques |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1880) Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh (1890) Albert Medal (1894) Copley Medal (1902) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | King's College London University of Glasgow University of Edinburgh University College, London |

Lister promoted the idea of sterile surgery while working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. Lister successfully introduced carbolic acid (now known as phenol) to sterilise surgical instruments and to clean wounds.

Applying Louis Pasteur's advances in microbiology, Lister championed the use of carbolic acid as an antiseptic, so that it became the first widely used antiseptic in surgery. He first suspected it would prove an adequate disinfectant because it was used to ease the stench from fields irrigated with sewage waste. He presumed it was safe because fields treated with carbolic acid produced no apparent ill-effects on the livestock that later grazed upon them.

Lister's work led to a reduction in post-operative infections and made surgery safer for patients, distinguishing him as the "father of modern surgery".[2]

Early life and education

Lister came from a prosperous Quaker home in West Ham, Essex, England, a son of wine merchant Joseph Jackson Lister, who was also a pioneer of achromatic object lenses for the compound microscope.[3]

At school, Lister became a fluent reader of French and German. A young Joseph Lister attended Benjamin Abbott's Isaac Brown Academy, a Quaker school in Hitchin in Hertfordshire (since converted into the "Lord Lister" public house).[4] As a teenager, Lister attended Grove House School in Tottenham, studying mathematics, natural science, and languages.

Lister attended University College, London,[5][6] one of only a few institutions which accepted Quakers at that time. He initially studied botany and obtained a bachelor of Arts degree in 1847.[7] He registered as a medical student and graduated with honours as Bachelor of Medicine, subsequently entering the Royal College of Surgeons at the age of 26. In 1854, Lister became both first assistant to and friend of surgeon James Syme at the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Royal Infirmary in Scotland. There he joined the Royal Medical Society and presented two dissertations, in 1855 and 1871, which are still in the possession of the Society today.[8]

Lister subsequently left the Quakers, joined the Scottish Episcopal Church, and eventually married Syme's daughter, Agnes.[9] On their honeymoon, they spent three months visiting leading medical institutes (hospitals and universities) in France and Germany. By this time, Agnes was enamoured of medical research and was Lister's partner in the laboratory for the rest of her life.[10]

Career and work

_surgeon_Wellcome_L0002075.jpg)

Before Lister's studies of surgery, most people believed that chemical damage from exposure to "bad air", or miasma, was responsible for infections in wounds. Hospital wards were occasionally aired out at midday as a precaution against the spread of infection via miasma, but facilities for washing hands or a patient's wounds were not available. A surgeon was not required to wash his hands before seeing a patient; in the absence of any theory of bacterial infection, such practices were not considered necessary. Despite the work of Ignaz Semmelweis and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., hospitals practised surgery under unsanitary conditions. Surgeons of the time referred to the "good old surgical stink" and took pride in the stains on their unwashed operating gowns as a display of their experience.[11]

While he was a professor of surgery at the University of Glasgow, Lister became aware of a paper published by the French chemist, Louis Pasteur, showing that food spoilage could occur under anaerobic conditions if micro-organisms were present. Pasteur suggested three methods to eliminate the micro-organisms responsible: filtration, exposure to heat, or exposure to solution/chemical solutions. Lister confirmed Pasteur's conclusions with his own experiments and decided to use his findings to develop antiseptic techniques for wounds.[12] As the first two methods suggested by Pasteur were unsuitable for the treatment of human tissue, Lister experimented with the third idea.

In 1834, Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge discovered phenol, also known as carbolic acid, which he derived in an impure form from coal tar. At that time, there was uncertainty between the substance of creosote – a chemical that had been used to treat wood used for railway ties and ships since it protected the wood from rotting – and carbolic acid.[13] Upon hearing that creosote had been used for treating sewage, Lister began to test the efficacy of carbolic acid when applied directly to wounds.[14]

Therefore, Lister tested the results of spraying instruments, the surgical incisions, and dressings with a solution of carbolic acid. Lister found that the solution swabbed on wounds remarkably reduced the incidence of gangrene.[15] In August 1865, Lister applied a piece of lint dipped in carbolic acid solution onto the wound of a seven-year-old boy at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, who had sustained a compound fracture after a cart wheel had passed over his leg. After four days, he renewed the pad and discovered that no infection had developed, and after a total of six weeks he was amazed to discover that the boy's bones had fused back together, without suppuration. He subsequently published his results in The Lancet in a series of six articles, running from March through July 1867.[16][17][3]

He instructed surgeons under his responsibility to wear clean gloves and wash their hands before and after operations with 5% carbolic acid solutions. Instruments were also washed in the same solution and assistants sprayed the solution in the operating theatre. One of his additional suggestions was to stop using porous natural materials in manufacturing the handles of medical instruments.[18]

Lister left Glasgow University in 1869, being succeeded by Prof George Husband Baird MacLeod.[19] Lister then returned to Edinburgh as successor to Syme as Professor of Surgery at the University of Edinburgh and continued to develop improved methods of antisepsis and asepsis. Amongst those he worked with there, who helped him and his work, was the senior apothecary and later MD, Dr Alexander Gunn. Lister's fame had spread by then, and audiences of 400 often came to hear him lecture. As the germ theory of disease became more understood, it was realised that infection could be better avoided by preventing bacteria from getting into wounds in the first place. This led to the rise of aseptic surgery. On the hundredth anniversary of his death, in 2012, Lister was considered by most in the medical field as "The Father of Modern Surgery".[14]

Criticism

Although Lister was so roundly honoured in later life, his ideas about the transmission of infection and the use of antiseptics were widely criticised in his early career.[3] In 1869, at the meetings of the British Association at Leeds, Lister's ideas were mocked; and again, in 1873, the medical journal The Lancet warned the entire medical profession against his progressive ideas.[20] However, Lister did have some supporters including Marcus Beck, a consultant surgeon at University College Hospital, who not only practiced Lister's antiseptic technique, but included it in the next edition of one of the main surgical textbooks of the time.[21][22]

Lister's use of carbolic acid proved problematic, and he eventually repudiated it for superior methods. The spray irritated eyes and respiratory tracts, and the soaked bandages were suspected of damaging tissue, so his teachings and methods were not always adopted in their entirety.[23] Because his ideas were based on germ theory, which was in its infancy, their adoption was slow.[24] General criticism of his methods was exacerbated by the fact that he found it hard to express himself adequately in writing, so they seemed complicated, unorganised, and impractical.[25]

Surgical technique

Lister moved from Scotland to King's College Hospital, in London. He was elected President of the Clinical Society of London.[26] He also developed a method of repairing kneecaps with metal wire and improved the technique of mastectomy. He was also known for being the first surgeon to use catgut ligatures, sutures, and rubber drains, and developing an aortic tourniquet.[27][28] He also introduced a diluted spray of carbolic acid combined with its surgical use, however he abandoned the carbolic acid sprays in the late 1890s after he saw it provided no beneficial change in the outcomes of the surgeries performed with the carbolic acid spray. The only reported reactions were minor symptoms that did not affect the surgical outcome as a whole, like coughing, irritation of the eye, and minor tissue damage among his patients who were exposed to the carbolic acid sprays during the surgery.[29][30]

Later life

Lister's wife had long helped him in research and after her death in Italy in 1893 (during one of the few holidays they allowed themselves) he retired from practice. Studying and writing lost appeal for him and he sank into religious melancholy. Despite suffering a stroke, he still came into the public light from time to time. He had for several years been a Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria, and from March 1900 was appointed the Serjeant Surgeon to the Queen,[31] thus becoming the senior surgeon in the Medical Household of the Royal Household of the sovereign. After her death the following year, he was re-appointed as such to her successor, King Edward VII.[32] On 24 August 1902, the King came down with appendicitis two days before his scheduled coronation. Like all internal surgery at the time, the appendectomy needed by the King still posed an extremely high risk of death by post-operational infection, and surgeons did not dare operate without consulting Britain's leading surgical authority. Lister obligingly advised them in the latest antiseptic surgical methods (which they followed to the letter), and the King survived, later telling Lister, "I know that if it had not been for you and your work, I wouldn't be sitting here today."[33]

Death

Lister died on 10 February 1912 at his country home (now known as Coast House[34][35]) in Walmer, Kent at the age of 84. After a funeral service at Westminster Abbey, his body was buried at Hampstead Cemetery in London in a plot to the south-east of central chapel.

Legacy and honours

—Albert Einstein's speech on intellectual freedom at the Royal Albert Hall, London after having fled Nazi Germany, 3 October 1933.[36]

In 1890, Lister was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh.

Lister was president of the Royal Society between 1895 and 1900. Following his death, a memorial fund led to the founding of the Lister Medal, seen as the most prestigious prize that could be awarded to a surgeon.

Lister's discoveries were greatly praised and in 1883 Queen Victoria created him a Baronet, of Park Crescent in the Parish of St Marylebone in the County of Middlesex.[37] In 1897 he was further honoured when Her Majesty raised him to the peerage as Baron Lister, of Lyme Regis in the County of Dorset.[38][39] In the 1902 Coronation Honours list published on 26 June 1902 (the original day of King Edward VII´s coronation),[40] Lord Lister was appointed a Privy Counsellor and one of the original members of the new Order of Merit (OM). He received the order from the King on 8 August 1902,[41][42] and was sworn a member of the council at Buckingham Palace on 11 August 1902.[43]

._Watercolour._Wellcome_V0018195.jpg)

Among foreign honours, he received the Pour le Mérite, one of Prussia's highest orders of merit. In 1889 he was elected as Foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Two postage stamps were issued in September 1965 to honour Lister for his pioneering work in antiseptic surgery.[44]

Lister is one of the two surgeons in the United Kingdom who have the honour of having a public monument in London. Lister's stands in Portland Place; the other surgeon is John Hunter. There is a statue of Lister in Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow, celebrating his links with the city. In 1903, the British Institute of Preventive Medicine was renamed Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine in honour of Lister.[45] The building, along with another adjacent building, forms what is now the Lister Hospital in Chelsea, which opened in 1985. In 2000, it became part of the HCA group of hospitals.

A building at Glasgow Royal Infirmary which houses cytopathology, microbiology and pathology departments was named in Lister's honour to recognise his work at the hospital. Lister Hospital in Stevenage, Hertfordshire is named after him. The Discovery Expedition of 1901–04 named the highest point in the Royal Society Range, Antarctica, Mount Lister.[46]

In 1879, Listerine antiseptic (developed as a surgical antiseptic but nowadays best known as a mouthwash) was named after Lister.[47] Microorganisms named in his honour include the pathogenic bacterial genus Listeria named by J. H. H. Pirie, typified by the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes, as well as the slime mould genus Listerella, first described by Eduard Adolf Wilhelm Jahn in 1906.[48] Lister is depicted in the Academy Award winning 1936 film, The Story of Louis Pasteur, by Halliwell Hobbes. In the film, Lister is one of the beleaguered microbiologist's most noted supporters in the otherwise largely hostile medical community, and is the key speaker in the ceremony in his honour.

Lister's name is one of twenty-three names featured on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine[49] – although the committee which chose the names to include on the frieze did not provide documentation about why certain names were chosen and others were not.[50]

Gallery

The Lord Lister Hotel in Hitchin, formerly Benjamin Abbott's Isaac Brown Academy, where Lister was a student from 1838 to 1841

The Lord Lister Hotel in Hitchin, formerly Benjamin Abbott's Isaac Brown Academy, where Lister was a student from 1838 to 1841 Memorial to Lister, Portland Place, London

Memorial to Lister, Portland Place, London_SURGEON_LIVED_HERE.jpg) Plaque at 12 Park Crescent, Regent's Park, London W1B 1PH

Plaque at 12 Park Crescent, Regent's Park, London W1B 1PH Lister Building located at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary

Lister Building located at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary- Lister Room at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, Scotland

Lister's name on the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, in Keppel Street

Lister's name on the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, in Keppel Street Coast House in Deal, with its blue plaque to Lister.

Coast House in Deal, with its blue plaque to Lister. Lister's hearse prior to his funeral service at Westminster Abbey, London

Lister's hearse prior to his funeral service at Westminster Abbey, London- Grave of Joseph Lister, West Hampstead Cemetery

See also

- Discoveries of anti-bacterial effects of penicillium moulds before Fleming

- Joseph Sampson Gamgee

- Museum of Health Care

References

- Cartwright, Frederick F. "Joseph Lister". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Pitt, Dennis; Aubin, Jean-Michel (1 October 2012). "Joseph Lister: father of modern surgery". Canadian Journal of Surgery. 55 (5): E8–E9. doi:10.1503/cjs.007112. ISSN 0008-428X. PMC 3468637. PMID 22992425.

- Barry, Rebecca Rego (2018). "From Barbers and Butchers to Modern Surgeons". Distillations. 4 (1): 40–43. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "History". The Lord Lister Hotel. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- John Bankston (2004). Joseph Lister and the Story of Antiseptics (Uncharted, Unexplored, and Unexplained). Bear, Del: Mitchell Lane Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58415-262-0.

- Lindsey Fitzharris (2017). The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister's Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine. New York: Scientific American: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 9780374117290.

- "Sketch of Sir Joseph Lister". Popular Science Monthly. March 1898. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- "RMS notable members".

- Ann Lamont (March 1992). "Joseph Lister: father of modern surgery". Creation. 14 (2): 48–51.

Lister married Syme's daughter Agnes and became a member of the Episcopal church

- Noble, Iris (1960). The Courage of Dr. Lister. New York: Julian Messner, Inc. p. 39.

- Millard, Candice (2011). Destiny of the Republic : A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385526265.

- Lister, Baron Joseph (1 August 2010). "The Classic: On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 468 (8): 2012–2016. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1320-x. ISSN 0009-921X. PMC 2895849. PMID 20361283.

- Schorlemmer, C. (30 March 1884). "The History of Creosote, Cedriret and Pittacal". Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry. 4: 152–157.

- Pitt, Dennis; Aubain, Jean-Michel (October 2012). "Joseph Lister: father of modern surgery". Canadian Journal of Surgery. 55 (5): E8–E9. doi:10.1503/cjs.007112. PMC 3468637. PMID 22992425.

- Lister, Joseph (18 July 1868). "An Address on the Antiseptic System of Treatment in Surgery". British Medical Journal. 2 (394): 53–56. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.394.53. PMC 2310876. PMID 20745202.

- Lister, Joseph (21 September 1867). "On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery". The Lancet. 90 (2299): 353–356. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)51827-4.

- Lister, Joseph (1 January 1870). "On the Effects of the Antiseptic System of Treatment Upon the Salubrity of a Surgical Hospital". The Lancet. 95 (2418): 2–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)31273-X.

- Metcalfe, Peter; Metcalfe, Roger (2006). Engineering Studies: Year 11. Glebe, N.S.W.: Pascal Press. p. 151. ISBN 9781741252491. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- Scotland (15 December 2016). "University of Glasgow :: Story :: Biography of Sir George Husband Baird MacLeod". Universitystory.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Boreham, F. W. Nuggets of Romance, p. 53.

- Sakula, Alex (1985). "Marcus Beck Library: Who Was Marcus Beck?". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 78 (12): 1047–1049. doi:10.1177/014107688507801214. PMC 1290062. PMID 3906125.

- England, Royal College of Surgeons of. "Beck, Marcus - Biographical entry - Plarr's Lives of the Fellows Online". livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Hurwitz, Brian; Dupree, Marguerite (March 2012). "Why celebrate Joseph Lister?". The Lancet. 379 (9820): e39–e40. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60245-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 22385682.

- Connor, J. J.; Connor, J. T. H. (1 June 2008). "Being Lister: ethos and Victorian medical discourse". Medical Humanities. 34 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1136/jmh.2008.000270. ISSN 1468-215X. PMID 23674533.

- Nakayama, Don (2018). "Antisepsis and Asepsis and How They Shaped Modern Surgery". ProQuest 2086806520. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Transactions of the Clinical Society of London Volume 18 1886". Clinical Society. Retrieved 23 October 2012. archive.org

- Bailard, Esther J. (1924). "Joseph Lister". The American Journal of Nursing. 24 (7): 576. JSTOR 3407651.

- Cope, Zachary (1967). "Joseph Lister, 1827–1912". The British Medical Journal. 2 (5543): 7–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5543.7. JSTOR 25411706. PMC 1841130. PMID 5336180.

- Hurwitz, Brian; Dupree, Marguerite (2012). "Why celebrate Joseph Lister?". The Lancet. 379 (9820): e39–e40. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60245-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 22385682.

- Lister, Joseph (1999). "Professor Lister on Antiseptic Surgery". The Lancet. 102 (2610): 353–354. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)65655-7. ISSN 0140-6736.

- "No. 27175". The London Gazette. 20 March 1900. p. 1875.

- "No. 27289". The London Gazette. 26 February 1901. p. 1414.

- Reminiscences of a Surgeon. Dorrance Publishing. p. 134.

- Coast House

- High Street Deal – Blue Plaque Walks in Deal

- "3 October 1933 – Albert Einstein presents his final speech given in Europe, at the Royal Albert Hall". Royal Albert Hall. 15 October 2017.

- "No. 25300". The London Gazette. 28 December 1883. p. 6687.

- "No. 26821". The London Gazette. 9 February 1897. p. 758.

- The Times, Friday, 1 Jan 1897; Issue 35089; p. 8; col A

- "The Coronation Honours". The Times (36804). London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- "Court Circular". The Times (36842). London. 9 August 1902. p. 6.

- "No. 27470". The London Gazette. 2 September 1902. p. 5679.

- "No. 27464". The London Gazette. 12 August 1902. p. 5173.

- "Antiseptic Surgery Stamps". BFFC. Retrieved 22 February 2017

- "Our Heritage". The Lister Institute. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- "Mount Lister". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- Hicks, Jesse. "A Fresh Breath". Thanks to Chemistry. Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Ramaswamy V, Cresence VM, Rejitha JS, Lekshmi MU, Dharsana KS, Prasad SP, Vijila HM (February 2007). "Listeria--review of epidemiology and pathogenesis" (PDF). Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection = Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 40 (1): 4–13. PMID 17332901.

- "Behind the Frieze – Baron Lister of Lyme Regis (1827–1912)". Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- LSHTM, LSHTM. "Behind the Frieze". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister |

- Works by Joseph Lister at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Lord Lister at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Lister at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Lord Lister at Internet Archive

- Works by Joseph Lister at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Lister Institute

- Collection of portraits of Lister at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Statue of Sir Joseph Lister by Louis Linck at The International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago

- Commemorative plaque to Lord Lister at the Edinburgh Medical School

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | Baron Lister 1897–1912 |

Extinct |

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New title | Baronet (of Park Crescent) 1883–1912 |

Extinct |