John Wayne Gacy

John Wayne Gacy (March 17, 1942 – May 10, 1994) was an American serial killer and sex offender known as the Killer Clown who assaulted and murdered at least 33 young men and boys. Gacy regularly performed at children's hospitals and charitable events as "Pogo the Clown" or "Patches the Clown", persona he devised. He was also active in his local community as a precinct captain and building contractor.

John Wayne Gacy | |

|---|---|

John Wayne Gacy in May 1978 | |

| Born | March 17, 1942 |

| Died | May 10, 1994 (aged 52) Stateville Correctional Center, Crest Hill, Illinois, US |

| Cause of death | Execution by lethal injection |

| Height | 5 ft 9 in (175 cm)[1] |

| Children | Michael Gacy, Christine Gacy |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | Death (12 counts) |

| Details | |

| Victims | 33+ |

Span of crimes | 1972–1978 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Illinois |

Date apprehended | December 21, 1978 |

| Imprisoned at | Menard Correctional Center |

It is believed all of Gacy's known murders were committed inside his ranch house in Norridge, a village in Norwood Park, metropolitan Chicago. Gacy would typically lure a victim to his home, dupe him into donning handcuffs on the pretext of demonstrating a magic trick, then rape and torture his captive before killing him by either asphyxiation or strangulation with a garrote. Twenty-six victims were buried in the crawl space of his home, three others were buried elsewhere on his property, and the last four were discarded in the Des Plaines River.

Gacy was convicted of the sodomy of a teenage boy in Iowa in 1968. He was sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment, but was released after 18 months. He first murdered in 1972, and at least 29 subsequent victims were killed after his divorce from his second wife in 1976. Investigation into the disappearance of Des Plaines teenager Robert Piest led to Gacy's arrest on December 21, 1978.

The conviction for 33 murders was the largest number of murders charged to one individual in United States until that time. Gacy was sentenced to death on March 13, 1980. On death row at Menard Correctional Center he spent much of his time painting. He was executed by lethal injection at Stateville Correctional Center on May 10, 1994.

Early life

John Wayne Gacy was born in Chicago, Illinois on March 17, 1942, the second child and only son of John Stanley Gacy (June 20, 1900 – December 25, 1969) and Marion Elaine Robinson (May 4, 1908 – December 6, 1989).[2] His father was an auto repair machinist and World War I veteran,[3] and his mother was a homemaker.[4][5] Gacy was of Polish and Danish ancestry.[6] His paternal grandparents (who spelled the family name as "Gatza" or "Gaca") had immigrated to the United States from Poland (then part of Prussia in Germany).[7][8]

Childhood

As a child, Gacy was overweight and not athletic. He was close to his two sisters and mother but endured a difficult relationship with his father, an alcoholic who was physically abusive to his wife and children.[9] Gacy seldom received his father's approval, later recollecting that, no matter what he achieved, he was "never good enough" in his father's eyes.[10] His father regularly belittled him, calling him "dumb and stupid" and comparing him unfavorably with his sisters.[11] Despite this, Gacy always denied ever hating his father.[12]

One of Gacy's earliest childhood memories was of being beaten with a leather belt at the age of four for accidentally disarranging car engine components his father had assembled.[13] On another occasion, he was struck across the head with a broomstick and rendered unconscious.[14] When he was six years old, Gacy stole a toy truck from a neighborhood store. His mother made him walk back to the store, return the toy and apologize to the owners. His mother informed his father, who beat Gacy with a belt as punishment. After this incident, Gacy's mother attempted to shield her son from his father's verbal and physical abuse,[15] yet this only succeeded in Gacy earning accusations that he was a "sissy" and a "Mama's boy"[16] who would "probably grow up queer".[17]

In 1949, Gacy's father was informed that his son and another boy had been caught sexually fondling a young girl.[18] Gacy's father whipped him with a razor strop as punishment. The same year,[19] Gacy was molested by a family friend,[16] a contractor who would take Gacy for rides in his truck and then fondle him. Gacy never told his father about these incidents, afraid that his father would blame him.[20]

Because of a heart condition, Gacy was ordered to avoid all sports at school.[20] During the fourth grade, Gacy began to experience blackouts. He was occasionally hospitalized because of these seizures, and also in 1957 for a burst appendix.[21] Gacy later estimated that between the ages of 14 and 18, he had spent almost a year in the hospital for these episodes, and attributed the decline of his grades to his missing school. His father suspected the episodes were an effort to gain sympathy and attention, and openly accused his son of faking the condition as the boy lay in a hospital bed.[22] Although his mother, sisters, and few close friends never doubted his illness, Gacy's medical condition was never conclusively diagnosed.[23]

One of Gacy's friends at high school recalled several instances in which his father ridiculed or beat his son without provocation. On one occasion in 1957, the same friend witnessed an incident at the Gacy household in which Gacy's father began shouting at his son for no reason, then began hitting him.[24] Gacy's mother attempted to intervene. The friend recalled that Gacy simply "put up his hands to defend himself", adding that he never struck his father back during these physical altercations.[25]

Career origins

In 1960, at the age of 18, Gacy became involved in politics, working as an assistant precinct captain for a Democratic Party candidate in his neighborhood. This decision earned more criticism from his father, who accused his son of being a "patsy". Gacy later speculated the decision may have been an attempt to seek the acceptance from others that he never received from his father.[26]

Las Vegas

The same year Gacy became a Democratic candidate, his father bought him a car, with the title of the vehicle being in his father's name until Gacy had completed the monthly repayments.[27] These repayments took several years to complete, and his father would confiscate the keys to the vehicle if Gacy did not do as his father said. On one occasion in 1962, Gacy bought an extra set of keys after his father confiscated the original set. In response, his father removed the distributor cap from the vehicle, withholding the component for three days. Gacy recalled that as a result of this incident, he felt "totally sick; drained".[28] When his father replaced the distributor cap, Gacy left the family home and drove to Las Vegas, Nevada, where he found work within the ambulance service before he was transferred to work as an attendant at Palm Mortuary.

In his role as a mortuary attendant, Gacy slept on a cot behind the embalming room.[29] He worked in this role for three months.[30] In this role, he observed morticians embalming dead bodies and later confessed that, on one evening while alone, he had clambered into the coffin of a deceased teenage male, embracing and caressing the body before experiencing a sense of shock.[31][lower-alpha 1] This prompted Gacy to call his mother the next day and ask whether his father would allow him to return home.[31] His father agreed and the same day, Gacy drove back to live with his family in Chicago.[33]

Springfield

Upon his return, despite the fact he had failed to graduate from high school, Gacy successfully enrolled in the Northwestern Business College,[34] from which he graduated in 1963. Gacy subsequently took a management trainee position within the Nunn-Bush Shoe Company.[35] In 1964, the shoe company transferred Gacy to Springfield to work as a salesman.[30] He was eventually promoted to manager of his department. In March of that year, he became engaged to Marlynn Myers, a co-worker in the department he managed.[36]

During his courtship with Marlynn, Gacy joined the local Jaycees and became a tireless worker for the organization, being named Key Man for the organization in April 1964.[37] The same year, Gacy had his second homosexual experience. According to Gacy, he acquiesced to this incident after one of his colleagues in the Springfield Jaycees plied him with drinks and invited him to spend the evening upon his sofa; the colleague then performed oral sex upon him while he was drunk.[38] By 1965, Gacy had risen to the position of vice-president of the Springfield Jaycees.[39] The same year, he was named as the third most outstanding Jaycee within the state of Illinois.[40]

Waterloo, Iowa

After a six-month courtship, Gacy and Myers married in September 1964.[41] Marlynn's father subsequently purchased three Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants in Waterloo, Iowa, and the couple moved to Waterloo so he could manage the restaurants, with the understanding that they would move into Marlynn's parents' home (which was vacated for the couple).[36][42] The offer was lucrative: Gacy would receive $15,000 per year (the equivalent of $115,513 as of 2020), plus a share of profits earned via the restaurants.[43] Following his obligatory completion of a managerial course, Gacy relocated to Waterloo with his wife later that year.[44]

Waterloo Jaycees

In Waterloo, Gacy joined the local chapter of the Jaycees, regularly offering extended hours to the organization in addition to the 12- and 14-hour days he worked managing three restaurants. Although considered ambitious and something of a braggart by other Jaycees, he was highly regarded for his fund-raising work. In 1967 he was named "outstanding vice-president" of the Waterloo Jaycees.[45] At Jaycee meetings Gacy often provided fried chicken and insisted on being called "Colonel" (for Colonel Sanders).[46] The same year, Gacy served on the Board of Directors for the Waterloo Jaycees.[47]

Gacy's wife gave birth to a son in February 1966 and a daughter in March 1967. Gacy himself later described this period of his life as "perfect" – he had earned his father's approval, which he had long sought. When Gacy's parents visited in July 1966, his father apologized for the abuse he had inflicted during Gacy's childhood, and said: "Son, I was wrong about you."[48]

Many Jaycees in Waterloo were involved in wife swapping,[38] prostitution, pornography, and drug use; Gacy was deeply involved in many of these activities and regularly had sex with local prostitutes.[49] He opened a "club" in his basement where his employees could drink alcohol and play pool. Although Gacy employed teenagers of both sexes at his restaurants, he socialized only with his young male employees. Many were given alcohol before Gacy made sexual advances; if rebuffed, Gacy would claim these advances were jokes or a test of morals.[50]

Assault of Donald Voorhees

In August 1967, Gacy committed his first known sexual assault upon a teenage boy. The victim was 15-year-old Donald Voorhees, the son of a fellow Jaycee. Gacy lured Voorhees to his house with the promise of showing him pornographic films.[51] Gacy plied Voorhees with alcohol and persuaded Voorhees to perform oral sex upon him. Over the following months, several other youths were sexually abused in a similar manner, including one whom Gacy encouraged to have sex with his own wife before blackmailing him into performing oral sex upon him.[50] Gacy tricked several teenagers into believing he was commissioned with conducting homosexual experiments in the interests of "scientific research", for which each was paid up to $50.[52]

In March 1968, Voorhees reported to his father that Gacy had sexually assaulted him. Voorhees Sr. immediately informed the police and Gacy was arrested and subsequently charged with oral sodomy in relation to Voorhees and the attempted assault of 16-year-old Edward Lynch.[53] Gacy vehemently denied the charges and demanded to take a polygraph test. This request was granted, although the results indicated Gacy was nervous when he denied any wrongdoing in relation to either Voorhees or Lynch.[54]

Gacy publicly denied any wrongdoing and insisted the charges against him were politically motivated – Voorhees Sr. had opposed Gacy's nomination for appointment as president of the Iowa Jaycees.[55] Several fellow Jaycees found Gacy's story credible and rallied to his support. However, on May 10, 1968, Gacy was indicted on the sodomy charge.[54]

Section of report detailing Gacy's 1968 psychiatric evaluation.[56]

On August 30, 1968, Gacy persuaded one of his employees, 18-year-old Russell Schroeder, to physically assault Voorhees in an effort to discourage the boy from testifying against him. Gacy promised to pay Schroeder $300 to lure Voorhees to a secluded spot, spray Mace in his face, and beat him. Schroeder agreed, and in early September, he lured Voorhees to an isolated county park, sprayed Mace into the youth's eyes, then beat him.[57][58]

Voorhees managed to escape, and immediately reported the assault to the police, identifying Schroeder as his attacker. Schroeder was arrested the following day. Despite initially denying any involvement, he soon confessed to having assaulted Voorhees, indicating that he had done so at Gacy's request. Gacy was arrested and additionally charged in relation to hiring Schroeder to assault and intimidate Voorhees.[59]

On September 12, Gacy was ordered to undergo a psychiatric evaluation at the Psychiatric Hospital of the State University of Iowa.[56] Two doctors examined Gacy over a period of 17 days before concluding he had an antisocial personality disorder (a disorder which incorporates constructs such as sociopathy and psychopathy),[60] was unlikely to benefit from any therapy or medical treatment, and that his behavior pattern was likely to bring him into repeated conflict with society.[61] The doctors also concluded he was mentally competent to stand trial.[61]

Conviction and imprisonment

.jpg)

On November 7, 1968 Gacy pled guilty to one count of sodomy in relation to Voorhees, but not guilty to the charges related to other youths. Gacy claimed Voorhees had offered his sexual services to him and that he had acted out of curiosity. His story was not believed. Gacy was convicted of sodomy on December 3 and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment, to be served at the Anamosa State Penitentiary.[61][62][63] That same day, his wife petitioned for divorce,[64] requesting award of the couple's home and property, sole custody of their two children, and alimony.[65] The Court ruled in her favor and the divorce was finalized on September 18, 1969. Gacy never saw his first wife or children again.[66]

During his incarceration in the Anamosa State Penitentiary, Gacy rapidly acquired a reputation as a model prisoner.[67] Within months of his arrival, he had risen to the position of head cook. He also joined the inmate Jaycee chapter and increased their membership figure from 50 to 650 in the span of less than 18 months. He is also known to have both secured an increase in the inmates' daily pay in the prison mess hall[68] and to have supervised several projects to improve conditions for inmates at the prison.[69] On one occasion, Gacy oversaw the installation of a miniature golf course in the prison's recreation yard.[70][lower-alpha 2]

In June 1969, Gacy first applied to the State of Iowa Board of Parole for early release: this application was denied. In preparation for a second scheduled parole hearing in May 1970, Gacy completed 16 high school courses, for which he obtained his diploma in November 1969.[72]

On Christmas Day 1969, Gacy's father died from cirrhosis of the liver.[72] When told the news, Gacy collapsed to the floor sobbing.[72] His request for supervised compassionate leave to attend the funeral was denied.[73]

Return to Chicago

Gacy was granted parole with 12 months' probation on June 18, 1970, after serving 18 months of his 10-year sentence.[74][75][76][77] Two of the conditions of his probation were for Gacy to relocate to Chicago to live with his mother and to observe a 10:00 p.m. curfew,[75] with the Iowa Board of Parole receiving regular updates as to his progress.[78]

Upon his release, Gacy told friend and fellow Jaycee Clarence Lane—who picked him up from the prison upon release and had remained steadfast in his belief of Gacy's innocence—that he would "never go back to jail" and that he intended to re-establish himself in Waterloo. However, within 24 hours of his release, Gacy relocated to Chicago to live with his mother.[75] He arrived in Chicago on June 19 and shortly thereafter obtained a job as a short-order cook in a restaurant.[79]

On February 12, 1971, Gacy was charged with sexually assaulting a teenage boy[80] who claimed that Gacy had lured him into his car at Chicago's Greyhound bus terminal and driven him to his home, where he had attempted to force the boy into sex. This complaint was dismissed when the boy failed to appear in court. The Iowa Board of Parole did not learn of this incident (which violated the conditions of his parole) and eight months later, in October 1971, Gacy's parole ended.[78] The following month, records of Gacy's previous criminal convictions in Iowa were sealed.[81][lower-alpha 3]

8213 West Summerdale Avenue

With financial assistance from his mother, Gacy bought a house in the village of Norridge in Norwood Park Township, an unincorporated area of Cook County, a part of metropolitan Chicago. The address, 8213 West Summerdale Avenue, is where he resided until his arrest in December 1978 and where all his known murders were committed.[84] He became active in his local community, and his neighbors considered him helpful; willing to loan his construction tools and plowing snow from neighborhood walks free of charge.[85] Between 1974 and 1978, he hosted annual summer parties attended by hundreds of people, including politicians.[86]

In August 1971, shortly after Gacy and his mother moved into the house, he became engaged to Carole Hoff, a divorcee with two young daughters. Hoff, whom he had briefly dated in high school, had been a friend of his younger sister. His fiancée and stepdaughters moved into his home soon after the couple announced their engagement.[87] Gacy's mother subsequently moved out of the house shortly before his wedding, which was held on July 1, 1972.[88]

One week before Gacy's wedding, on June 22, he was arrested and charged with aggravated battery and reckless conduct. The arrest was in response to a complaint filed by a youth who claimed that Gacy had flashed a sheriff's badge, lured him into his car, and forced him to perform oral sex.[89] These charges were dropped after the complainant attempted to blackmail Gacy.[90]

PDM Contractors

In 1971, Gacy established a part-time construction business, PDM Contractors (PDM being the initials for 'Painting, Decorating, and Maintenance').[91] With the approval of his probation officer, he was allowed to work evenings to commit to his employment contracts while working as a cook during the day. The business initially undertook minor repair work, such as sign-writing, pouring concrete, and redecorating, but later expanded to include projects such as interior design, remodeling, installation, assembly, and landscaping. In mid-1973, Gacy quit his job as a cook in order that he could fully commit to his construction business.[92]

By 1975, PDM was expanding rapidly and Gacy was working up to 16 hours per day. In March 1977, he became a supervisor for PE Systems, a firm specializing in the remodeling of drugstores. Between PE Systems and PDM, Gacy worked on up to four projects at once and frequently traveled to other states.[93] By 1978, PDM's annual revenue was over $200,000.[94]

Employees

Much of the labor workforce of PDM consisted of high school students and young men.[95] Gacy would often proposition his workers for sex, or insist on sexual favors in return for acts such as the loaning of his vehicles, financial assistance, or promotions.[96] He also claimed to own guns, telling employee Arthur Peterson: "Do you know how easy it would be to get one of my guns and kill you — and how easy it would be to get rid of the body?"[97]

In 1973, Gacy and a teenage employee of PDM traveled to Florida to view property Gacy had purchased. On the first night in Florida, Gacy raped the employee in their hotel room.[98] After returning to Chicago, he drove to Gacy's house and beat him in his yard. Gacy told his wife he had been attacked for refusing to pay the employee for poor-quality work.[99]

Gacy hired 15-year-old Anthony Antonucci in May 1975. In July 1975, Gacy went to Antonucci's home. The two drank a bottle of wine, then watched a heterosexual stag film before Gacy wrestled Antonucci to the floor and cuffed his hands behind his back.[100] One cuff was loose and Antonucci freed his arm while Gacy was out of the room. When Gacy returned, Antonucci—a high school wrestler—pounced upon him. He wrestled Gacy to the floor, obtained possession of the handcuff key and cuffed Gacy's hands behind his back. Gacy at first threatened Antonucci, then calmed down and promised to leave if Antonucci would remove the handcuffs. Antonucci agreed and Gacy left.[100] Antonucci later recalled that Gacy told him: "Not only are you the only one who got out of the cuffs, you got them on me".[101]

Cram and Rossi

On July 26, 1976, Gacy employed 18-year-old David Cram. On August 21, Cram moved into his house.[102] The following day, Gacy conned Cram into donning handcuffs while Cram was drunk. Gacy swung Cram around while holding the chain linking the cuffs, then said he intended to rape him. Cram kicked Gacy in the face and freed himself from the handcuffs. One month later, Gacy appeared at Cram's bedroom door with the intention to rape him, saying: "Dave, you really don't know who I am. Maybe it would be good if you give me what I want."[103] Cram resisted and Gacy left the bedroom. Shortly thereafter, Cram moved out and left PDM, although he did periodically work for Gacy over the following two years.[104]

Shortly after Cram moved out of Gacy's house another employee, 18-year-old Michael Rossi, moved in.[105][106][107] Rossi had worked for PDM Contractors since May 1976.[108] He lived with Gacy until April 1977.[109][lower-alpha 4]

Politics

Gacy became active in local Democratic Party politics, initially offering the labor services of his employees to clean party headquarters for free.[110] He was rewarded for his community service by being appointed to serve upon the Norwood Park Township street lighting committee,[82] subsequently earning the title of precinct captain.[83][111]

In 1975, Gacy was appointed director of Chicago's annual Polish Constitution Day Parade—he supervised the annual event from 1975 until 1978. Through his work with the parade, Gacy met and was photographed with First Lady Rosalynn Carter on May 6, 1978.[112] She signed one photo: "To John Gacy. Best wishes. Rosalynn Carter".[113] The event later became an embarrassment to the United States Secret Service, as in the pictures taken, Gacy can be seen wearing an "S" pin, indicating a person who has been given special clearance by the Secret Service.[114]

Divorce

By 1975, Gacy had told his wife that he was bisexual.[115] After the couple had sex on Mother's Day that year, he informed her this would be "the last time" they would ever have sex.[98] He began spending most evenings away from home only to return in the early hours of the morning with the excuse he had been working late.[116] His wife observed Gacy bringing teenage boys into his garage and also found gay pornography and men's wallets and identification cards inside the house.[117] When she once confronted Gacy about who these items belonged to, he angrily informed her the property was none of her business.[117]

Following a heated argument regarding her failing to balance a checkbook correctly in October 1975,[118] Carole Gacy asked her husband for a divorce. Gacy agreed to his wife's request although, by mutual consent, Carole continued to live at 8213 West Summerdale until February 1976, when she and her daughters moved into their own apartment. One month later, on March 2, the Gacys' divorce—decreed upon the false grounds of Gacy's infidelity with women[119]—was finalized.[120][121][lower-alpha 5]

Pogo the Clown

.jpg)

Through his membership in a local Moose Club, Gacy became aware of a "Jolly Joker" clown club, whose members regularly performed at fund-raising events and parades in addition to voluntarily entertaining hospitalized children.[123] In late 1975, Gacy joined the Jolly Jokers and created his own performance characters: "Pogo the Clown" and "Patches the Clown."[124][lower-alpha 6] He performed as Pogo or Patches at numerous local parties, political functions, charitable events, and children's hospitals.[126] He designed his own costumes and taught himself how to apply clown makeup.[lower-alpha 7] Gacy was also known to occasionally remain in his clowning garb after a performance. On several occasions, he is known to have arrived, dressed in his clowning garb, at a favorite drinking venue, "The Good Luck Lounge", with the explanation he had performed at a charitable event and was stopping for a social drink before heading home.[127][128] For these reasons, Gacy is known as the "Killer Clown."

Murders

Gacy typically abducted his victims from Chicago's Greyhound Bus station, from Bughouse Square, or simply off the streets. The victims were often grabbed by force or conned into believing Gacy—often carrying a sheriff's badge and placing spotlights on his black Oldsmobile—was a policeman.[129] Others were lured to his house with either the promise of a job with his construction company, or an offer of drink, drugs, or money for sex.[130]

Inside Gacy's home, his usual modus operandi was to ply a youth with drink, drugs, or generally gain his trust. Gacy would then produce a pair of handcuffs, occasionally as part of a clowning routine. He typically cuffed his own hands behind his back, then surreptitiously released himself with the key, which he hid between his fingers, before offering to show his intended victim how to release himself from the handcuffs.[131][132] With his victim manacled and unable to free himself, Gacy then made a statement to the effect of: "The trick is, you have to have the key", before proceeding to rape and torture his captive.[133] Gacy referred to this act of restraining his victim as the "handcuff trick".[134]

Having restrained his victim, Gacy frequently sat upon his captive's chest before forcing his victim to fellate him.[135] He then proceeded to further rape and torture his captive. Acts of torture inflicted upon Gacy's victims included burning with cigars, his sitting upon their backs as he forced his captive to imitate a horse with makeshift reins around their necks,[136] and violation with foreign objects as Gacy repeatedly informed his captive to inform him of his enjoyment at his treatment.[137] Several victims were dragged or forced to crawl[138] into his bathroom where they were partly drowned in the bathtub before Gacy repeatedly revived them, enabling him to continue his prolonged assault.[139] The victims were usually lured alone to his house, although on approximately three occasions, Gacy had what he called "doubles"—occasions wherein he killed two victims on the same evening.[140] With the exceptions of his first and last victims, all were murdered between 3:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m.[141]

Gacy typically murdered his victims by placing a rope tourniquet around their neck before progressively tightening the rope with a hammer handle.[142][143] He referred to this as the "rope trick." Occasionally, the victim convulsed for an "hour or two" before dying, although several of his victims died by asphyxiation from cloth gags stuffed deep into their throat.[133]

After death, the victims' bodies were typically stored beneath his bed for up to 24 hours before Gacy buried his victim in the crawl space, where he periodically poured quicklime to hasten the decomposition of the bodies.[144] The bodies of some victims would be taken to his garage and embalmed prior to their burial.[145]

Murder of Timothy McCoy

Gacy's first known murder occurred on January 2, 1972. According to Gacy's later account, following a family party, he decided to drive to the Civic Center to view a display of ice sculptures before luring a 16-year-old named Timothy Jack McCoy from Chicago's Greyhound bus terminal into his car. McCoy was traveling from Michigan to Omaha. Gacy took McCoy on a sightseeing tour of Chicago, and then drove him to his home with the promise that he could spend the night and be driven back to the station in time to catch his bus.[146] Prior to McCoy's identification, he was known simply as the "Greyhound Bus Boy".[147]

Gacy claimed he woke early the following morning to find McCoy standing in his bedroom doorway with a kitchen knife in his hand.[148] He then jumped from his bed and McCoy raised both arms in a gesture of surrender, tilting the knife upwards and accidentally cutting Gacy's forearm.[149][lower-alpha 8] He then twisted the knife from McCoy's wrist, banged his head against his bedroom wall, kicked him against his wardrobe and walked towards him. McCoy then kicked Gacy in the stomach, doubling him over. Gacy then grabbed McCoy, wrestled him to the floor, then stabbed him repeatedly in the chest as he straddled him.[115]

As McCoy lay dying, Gacy claimed he washed the knife in his bathroom, then went to his kitchen and saw an opened carton of eggs and a slab of unsliced bacon on his kitchen table. McCoy had also set the table for two; he had walked into Gacy's room to wake him while absentmindedly carrying the kitchen knife in his hand.[151] Gacy buried McCoy in his crawl space and later covered his grave with a layer of concrete.[152] In an interview several years after his arrest, Gacy stated that immediately after killing McCoy, he felt "totally drained", yet noted as he listened to the "gurgulations" as McCoy lay gasping for air that he had experienced a mind-numbing orgasm as he had stabbed him.[148] He added: "That's when I realized that death was the ultimate thrill."[151]

Second murder

Gacy later stated that the second time he committed murder was around January 1974. The victim is believed to have been an unidentified teenager with medium brown hair and estimated to be aged between 14 and 18 whom Gacy strangled before stowing his body in his closet prior to burial.[153] The victim was found wrapped within several plastic bags and wore a silver ring on the fourth finger of his left hand, indicating the possibility he had been married.[154] Gacy later stated that fluid leaked out of the mouth and nose of this body while stored in his closet, staining his carpet.[155] As a result of this experience, Gacy regularly stuffed cloth rags or the victims' own underwear in their mouths to prevent a recurrence of this incident. This particular unidentified victim was buried about 15 feet (4.6 m) from the barbecue pit in Gacy's backyard.[156]

Murder of John Butkovich

One week after the attempted assault of Antonucci, on July 31, 1975, another of Gacy's employees, an 18-year-old from Lombard, John Butkovich, disappeared.[157] Butkovich's car was found abandoned in a parking lot with his jacket and wallet inside and the keys still in the ignition.[158]

The day before his disappearance, Butkovich had confronted Gacy over two weeks' outstanding back pay. Butkovich's father, a Yugoslav immigrant, called Gacy, who claimed he was happy to help search for his son but was sorry Butkovich had "run away".[159] When questioned by police, Gacy said Butkovich and two friends had arrived at his house demanding the overdue pay, but that a compromise had been reached, and all three had left. Over the following three years, Butkovich's parents called police more than 100 times, urging them to investigate Gacy further.[159][160]

Gacy later admitted to luring Butkovich to his home, ostensibly to settle the issue of his overdue wages, on a date his wife and stepchildren were visiting his sister in Arkansas. He offered Butkovich a drink, then conned him into allowing his wrists to be cuffed behind his back. Gacy said he "sat on the kid's chest for a while" before he strangled him. He initially stowed Butkovich's body in his garage, intending to later bury the body in the crawl space.[161] When his wife and stepdaughters returned to Illinois earlier than expected, Gacy buried the body of Butkovich under the concrete floor of the garage.[162]

Cruising years

In addition to being the year of his business expanding, Gacy freely admitted 1975 was also when he began to increase the frequency of his excursions for sex with young males.[163] He often referred to these jaunts as "cruising".[164] Gacy committed most of his murders between 1976 and 1978, as he largely lived alone following his divorce. He later referred to these as his "cruising years".

Although Gacy remained gregarious and civic-minded, several neighbors noticed erratic changes in his behavior after his 1976 divorce. This included keeping company with young males, hearing his car arrive or depart in the early hours of the morning, or seeing lights in his home switch on and off.[119] One neighbor later recollected that, for several years, she and her son had repeatedly been awoken by the repeated sounds of muffled high-pitched screaming, shouting, and crying in the early morning hours, which she and her son identified as emanating from a house adjacent to theirs on Summerdale Avenue.[165]

1976

One month after his divorce was finalized, Gacy abducted and murdered 18-year-old Darrell Samson. Samson was last seen alive in Chicago on April 6, 1976.[166] Five weeks later, on the afternoon of May 14, 15-year-old Randall Reffett disappeared while walking home from Senn High School; he was gagged with a cloth,[167] causing him to die of asphyxiation.[133] Hours after Reffett had been abducted, 14-year-old Samuel Stapleton vanished as he walked to his home from his sister's apartment.[119] Both victims were buried in the same grave in the crawl space.[168]

On June 3, 1976, Gacy killed a 17-year-old Lakeview teenager named Michael Bonnin. He disappeared while traveling from Chicago to Waukegan,[169] and was strangled with a ligature and buried in the crawl space.[167] Ten days later, a 16-year-old Uptown youth named William Carroll was murdered and buried directly beneath Gacy's kitchen. Carroll may have been the first of four males known to have been murdered between June 13 and August 6, 1976, and who were buried in a common grave located beneath Gacy's kitchen and laundry room.[170][lower-alpha 9]

The three identified youths killed between June 13 and August 6 were aged between 16 and 17 years old, whereas the only unidentified male known to have been murdered between these dates is a man with medium dark brown hair estimated to have been aged between 23 and 30 years old and between 5 ft 1 in and 5 ft 6 in (150 and 170 cm) tall. This man had two missing upper front teeth at the time of his disappearance,[172] leading investigators to believe this particular victim most likely wore a denture. He was buried directly beneath the body of a 16-year-old Minnesota youth named James Haakenson, who is last known to have phoned his family on August 5, and whose body was itself buried directly beneath that of a 17-year-old Bensenville youth named Rick Johnston, who was last seen alive on August 6.[173][174][lower-alpha 10]

Two further unidentified males are estimated to have been killed between August and October 1976. One of these victims was buried directly above the body of William Carroll, who had been murdered on June 13, yet higher than the body of Rick Johnston, who was last seen on August 6. This particular unidentified male is estimated to have been aged between 15 and 24 years old and had light brown hair. Sequential burial patterns of victims within the crawl space, plus the circumstantial fact that Cram had not lived with Gacy until August 21, leave a possible date of between August 6 and 20, 1976 as the time this particular man was murdered.[177] The second unidentified male likely to have been murdered between August and October 1976 is a youth with dark brown, wavy hair, between 18 and 22 years old, and who is known to have suffered from an abscessed tooth. This victim may have been killed somewhat before early October 1976, when Gacy had an employee dig a trench in the northeast corner of the crawlspace, where this victim's body was later found.[177]

On October 24, 1976, Gacy abducted and killed teenage friends Kenneth Parker and Michael Marino:[178] the two were last seen outside a restaurant on Clark Street. Both were strangled and buried in the same grave in the crawl space. Two days later, a 19-year-old employee of PDM, William Bundy, disappeared after informing his family he was to attend a party. Bundy was also strangled and buried in the crawl space, directly beneath Gacy's master bedroom.[179]

In December 1976, another PDM employee, 17-year-old Gregory Godzik, disappeared: he was last seen by his girlfriend outside her house after he had driven her home following a date.[180] Godzik had worked for PDM for only three weeks before he disappeared. In the time he had worked for Gacy, he had informed his family Gacy had had him "dig trenches for some kind of (drain) tiles" in his crawl space.[106] Godzik's car was later found abandoned in Niles. His parents and older sister, Eugenia, contacted Gacy about Greg's disappearance. Gacy claimed to the family that Greg had run away from home, having indicated to Gacy before his disappearance that he wished to do so. Gacy also claimed to have received an answering machine message from Godzik shortly after he had disappeared. When asked if he could play back the message to Godzik's parents, Gacy stated that he had erased it.[106][181]

1977

On January 20, 1977, John Szyc, a 19-year-old acquaintance of Butkovich, Godzik, and Gacy, disappeared. Szyc was lured to Gacy's house on the pretext of selling his Plymouth Satellite to Gacy,[105] who later sold Szyc's car to Michael Rossi for $300.[182] Szyc was buried in Gacy's crawl space directly above the body of Godzik.[183]

Between December 1976 and March 1977, Gacy is known to have killed an unidentified man with brown hair and estimated to be between 22 and 32 years old.[184] An inscription upon a key fob found among the personal artifacts buried with this unknown victim suggests his first name may have been Greg or Gregory.[185] His body was buried in the crawl space beneath the body of 20-year-old Jon Prestidge, a Michigan man visiting friends in Chicago whom Gacy killed on March 15.

After the murder of Prestidge, Gacy is believed to have murdered one further unidentified youth exhumed from his crawl space, although the timing of this particular youth's murder is inconclusive. He was buried parallel to the wall of Gacy's crawl space directly beneath the entrance to his home. The two victims murdered on the same day in May 1976 were buried alongside him, yet sequential burial patterns of three victims murdered in 1977 leave an equal possibility this particular victim may have been murdered in the spring or summer of 1977. All that is known about this youth is that he was aged between 17 and 21 years old and that he had suffered a fractured left collarbone before his disappearance.[186]

On July 5, Gacy killed a 19-year-old from Crystal Lake named Matthew Bowman. Bowman was last seen by his mother at a suburban train station.[187] He was buried in the crawl space with the tourniquet used to strangle him still knotted around his neck.[188]

The following month, Rossi was arrested for stealing gasoline from a service station while driving Szyc's car. The attendant noted the license plate number and police traced the car to Gacy's house. When questioned, Gacy told officers that Szyc had sold the car to him in February with the explanation that he needed money to leave town. A check of the VIN number confirmed the car had belonged to Szyc.[189] The police did not pursue the matter further,[190] although they did inform Szyc's mother that her son had sold his car to Gacy in February.[191]

By the end of 1977, Gacy is also known to have murdered an additional six young men between the ages of 16 and 21. The first of these six victims, 18-year-old Robert Gilroy, was last seen alive on September 15. Gilroy—the son of a Chicago police sergeant[192]—was suffocated and buried in the crawl space. On September 12, Gacy had flown to Pittsburgh to supervise a remodeling project and did not return to Chicago until September 16.[193] As Gacy is known to have been in another state at the time Gilroy was last seen, this is cited to support Gacy's claim of being assisted by one or more accomplices. Ten days after Gilroy was last seen, 19-year-old former U.S. Marine John Mowery disappeared after leaving his mother's house to walk to his own apartment. Mowery was strangled and buried in the northwest corner of the crawl space perpendicular to the body of William Bundy.[179]

On October 17, 21-year-old Minnesota native Russell Nelson disappeared: he was last seen outside a Chicago bar. Nelson died of suffocation and was also buried in the crawl space. Less than four weeks later, 16-year-old Kalamazoo teenager Robert Winch was murdered and buried in the crawl space, and on November 18, 20-year-old father-of-one Tommy Boling disappeared after leaving a Chicago bar. Both Winch and Boling were strangled[194] and buried in the crawl space directly beneath the hallway.[195]

Three weeks after the murder of Tommy Boling, on December 9, a 19-year-old U.S. Marine named David Talsma disappeared after informing his mother he was to attend a rock concert in Hammond.[196] Talsma was strangled with a ligature and buried in the crawl space.[197]

On December 30, 1977, Gacy abducted 19-year-old student Robert Donnelly from a Chicago bus stop at gunpoint.[198] Gacy drove Donnelly to his home, where Donnelly was raped, tortured, and repeatedly had his head dunked into a bathtub until he passed out. Donnelly later testified at Gacy's trial that he was in such pain that he asked Gacy to kill him;[199] Gacy replied, "I'm getting round to it." After several hours Gacy drove Donnelly to his workplace and released him, first warning him that if he complained to police they would not believe him.[200]

1978

Donnelly reported the assault and Gacy was questioned by police on January 6, 1978. Gacy admitted to having had "slave-sex" with Donnelly, but insisted everything was consensual. The police believed him and no charges were filed.[201] The following month, Gacy killed 19-year-old William Kindred, who disappeared on February 16, after telling his fiancée he was to spend the evening in a bar.[202] Kindred was the final victim to be buried in Gacy's crawl space.[203][204]

On March 21, Gacy lured 26-year-old Jeffrey Rignall into his car. Upon entering the car, the young man was chloroformed and driven to the house on Summerdale, where he was raped, tortured with various instruments including lit candles and whips, and repeatedly chloroformed into unconsciousness.[205] Rignall was then driven to Lincoln Park, where he was dumped, unconscious but alive. He was later informed the chloroform had permanently damaged his liver.[205]

Rignall managed to stagger to his girlfriend's apartment. Police were again informed of the assault but did not investigate Gacy. Rignall was able to recall, through the haze of that night, the Oldsmobile, the Kennedy Expressway and particular side streets. He staked out the exit on the Expressway when in April he saw the Oldsmobile, which Rignall and his friends followed to 8213 West Summerdale.[206] Police issued an arrest warrant, and Gacy was arrested on July 15.[207] He was facing an impending trial for battery against Rignall when he was arrested.[208]

By 1978, the crawl space could store no further bodies.[58][67][209] Gacy later confessed to police that he initially considered stowing bodies in his attic, but had been worried of complications arising from "excessive leakage".[210] Therefore, he chose to dispose of his victims off the I-55 bridge into the Des Plaines River.[211] Gacy stated he had thrown five bodies off the I-55 bridge into the Des Plaines River in 1978, one of which he believed had landed upon a passing barge.[84] Only four of these five bodies were ever found.[212]

The first known victim thrown from the I-55 bridge into the Des Plaines River, 20-year-old Timothy O'Rourke, was killed in mid-June after leaving his Dover Street apartment, having informed his roommate of his intention to purchase cigarettes; his body was found 6 miles (10 km) downstream on June 30.[213][214]

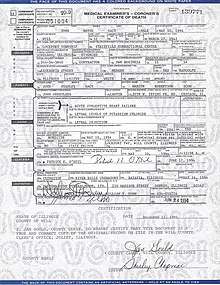

On November 4, Gacy killed 19-year-old Frank Landingin. His body was found in the Des Plaines River on November 12. Less than three weeks later, on November 24, a 20-year-old Elmwood Park resident, James Mazzara, disappeared after sharing Thanksgiving dinner with his family; his body was found on December 28. The cause of death in the case of Landingin was certified as suffocation through his own underwear being lodged down his throat, plugging his airway and effectively causing him to drown in his own vomit.[215] Mazzara had been strangled with a ligature.[216][217]

Murder of Robert Piest

On the afternoon of December 11, 1978, Gacy visited the Nisson Pharmacy in Des Plaines to discuss a potential remodeling deal with the store owner, Phil Torf. While Gacy was within earshot of 15-year-old, part-time employee Robert Piest, he mentioned that his firm hired teenage boys at a starting wage of $5 per hour—almost double the pay Piest earned at the pharmacy.[218][219]

Shortly after Gacy left the pharmacy, Piest informed his mother—who had arrived at the pharmacy to drive her son home—that "some contractor wants to talk to me about a job". Piest left the store, promising to return shortly.[220] He was murdered shortly after 10:00 p.m. at Gacy's home. Gacy later stated that as he placed the tourniquet around Piest's neck, the boy was "crying, scared".[221] He also admitted to having received a phone call from a business acquaintance as Piest lay dying on his bedroom floor.[222]

Investigation

When Piest failed to return, his family filed a missing person report on their son with the Des Plaines police. Torf named Gacy as the contractor Piest had most likely left the store to talk with about a job.[223] Convinced Piest had not run away from home, Lieutenant Joseph Kozenczak chose to investigate Gacy further.[224]

Kozenczak and two other Des Plaines police officers visited Gacy at his home the following evening. Gacy indicated he had seen two youths working at the pharmacy and that he had asked one of them—whom he believed to be Piest—whether any remodeling materials were present in the rear of the store.[225] He was adamant, however, that he had not offered Piest a job and promised to come to the station later that evening to make a statement confirming this, indicating he was unable to do so at that moment as his uncle had just died. When questioned as to how soon he could come to the police station, he responded: "You guys are very rude. Don't you have any respect for the dead?"[226]

At 3:20 a.m., Gacy, covered in mud, arrived at the police station, claiming he had been involved in a car accident.[227] Upon returning to the police station later that day, Gacy denied any involvement in the disappearance of Piest and repeated that he had not offered him a job. When asked why he had returned to the pharmacy at 8:00 p.m. Gacy claimed he had done so in response to a phone call from Torf informing him he had left his appointment book at the store. Detectives had already spoken with Torf, who had stated he had placed no such call to Gacy.[228] At the request of detectives, Gacy prepared a written statement detailing his movements on December 11.[229]

Revelations

Des Plaines police were convinced Gacy was behind Piest's disappearance and checked Gacy's record, discovering that he had an outstanding battery charge against him in Chicago and had served a prison sentence in Iowa for the sodomy of a 15-year-old boy.[230] A search of Gacy's house on December 13 was ordered by a judge at the request of detectives and revealed several suspicious items. These included a syringe, several police badges, and a 6mm Brevettata starter pistol. They also found handcuffs, books on homosexuality and pederasty, a 39 inch long two-by-four with two holes drilled into each end,[231] several driver's licenses, a blue hooded parka and underwear too small to fit Gacy.[232]

In the northwest bedroom, investigators found a Maine West High School ring. This item initially interested investigators as Piest had attended Maine West, but the ring was not his. This ring was a class of 1975 ring engraved with the initials J.A.S.[233][234] A photo receipt from Nisson Pharmacy was also recovered from a trash can.[232]

Gacy's Oldsmobile and other PDM work vehicles were confiscated by the Des Plaines police, who assigned two two-man surveillance teams to monitor Gacy on a rotational twelve-hour basis as they continued their investigation into his background and potential involvement in Piest's disappearance.[235] These surveillance teams consisted of officers Mike Albrecht and David Hachmeister, and Ronald Robinson and Robert Schultz.[236] The following day, investigators received a phone call from Michael Rossi, who informed the investigators both of Gregory Godzik's disappearance and the fact that another PDM employee, Charles Hattula, had been found drowned in an Illinois river earlier that year.[237][238]

On December 15, Des Plaines investigators obtained further details upon Gacy's battery charge, learning the complainant, Jeffrey Rignall, had reported that Gacy had lured him into his car, then chloroformed, raped and tortured him before dumping him, with severe chest and facial burns and rectal bleeding, in Lincoln Park the following morning. In an interview with Gacy's former wife the same day, they learned of the disappearance of John Butkovich.[239] The same day, the Maine West High School ring was traced to a John Alan Szyc.[240] An interview with Szyc's mother revealed that several items from her son's apartment were also missing, including a Motorola TV set.[241]

By December 16, Gacy was becoming affable with the surveillance detectives, regularly inviting them to join him for meals in restaurants and occasionally for drinks in bars or within his home. He repeatedly denied that he had anything to do with Piest's disappearance and accused the officers of harassing him because of his political connections or because of his recreational drug use. Knowing these officers were unlikely to arrest him on anything trivial, he openly taunted them by flouting traffic laws and succeeded in losing his pursuers on more than one occasion.[242]

On December 17, investigators conducted a formal interview of Michael Rossi, who informed them Gacy had sold Szyc's vehicle to him with the explanation that he had bought the car from Szyc because Szyc needed money to move to California. A further examination of Gacy's Oldsmobile was conducted on this date. In the course of examining the trunk of the car, the investigators discovered a small cluster of fibers which may have been human hair. These fibers were sent for further analysis. That evening, officers conducted a test using three trained German shepherd search dogs to determine whether Piest had been present in any of Gacy's vehicles.[243] The dogs were allowed to examine each of Gacy's vehicles, whereupon one dog approached Gacy's Oldsmobile and lay upon the passenger seat in what the dog's handler informed investigators was a "death reaction", indicating the body of Robert Piest had been present in this vehicle.[243]

That evening, Gacy invited two of the surveillance detectives to a restaurant for a meal. In the early hours of December 18, he invited the same officers into another restaurant where, over breakfast, he talked of his business, his marriages and his activities as a registered clown. At one point during this conversation, Gacy remarked to one of the two surveillance detectives: "You know ... clowns can get away with murder."[244][245]

Civil suit

By December 18, Gacy was beginning to show visible signs of strain as a result of the constant surveillance: he was unshaven, looked tired, appeared anxious and was drinking heavily. That afternoon, he drove to his lawyers' office to prepare a $750,000 civil suit against the Des Plaines police,[246] demanding that they cease their surveillance. The same day, the serial number of the Nisson Pharmacy photo receipt found in Gacy's kitchen was traced to 17-year-old Kim Byers, a colleague of Piest at Nisson Pharmacy, who admitted when contacted in person the following day that she had worn the jacket on December 11 to shield herself from the cold and had placed the receipt in the parka pocket just before she gave the coat to Piest as he left the store to talk with a contractor.[247] This revelation contradicted Gacy's previous statements that he had had no contact with Robert Piest on the evening of December 11.[248]

The same evening, Michael Rossi was interviewed a second time: on this occasion, Rossi was more cooperative, informing detectives that in the summer of 1977, Gacy had had him spread ten bags of lime in the crawl space of the house.[249]

On December 19, investigators began compiling evidence for a second search warrant of Gacy's house. The same day, Gacy's lawyers filed the civil suit against the Des Plaines police. The hearing of the suit was scheduled for December 22. That afternoon, Gacy invited two of the surveillance detectives inside his house. On this occasion, as one officer distracted Gacy with conversation, another officer walked into Gacy's bedroom in an unsuccessful attempt to write down the serial number of the Motorola TV set they suspected belonged to John Szyc. While flushing Gacy's toilet, this officer noticed a smell he suspected could be that of rotting corpses emanating from a heating duct; the officers who previously searched Gacy's house had failed to notice this, as on that occasion the house had been cold.[235]

Both David Cram and Michael Rossi were interviewed by investigators on December 20. Rossi had agreed to be interviewed in relation to his possible links with John Szyc as well as the disappearance of Robert Piest. When questioned by Kozenczak as to where he believed Gacy had placed Piest's body, Rossi replied: "In the crawl space; he could have put him in the crawl space."[250] A polygraph test showed his responses to questions to be inconclusive; however, upon his agreeing to a subsequent visual test in which a map of Cook County was divided into 12 grid sections numbered 1 to 12, with Gacy's home marked in the fourth grid section, Kozenczak noted an extreme response in Rossi's blood pressure when asked: "Is the body of Robert Piest buried in grid number 4?"[251] Upon hearing this question, Rossi refused to continue the polygraph questioning, although he did discuss further his digging trenches in the crawl space and remarked upon Gacy's insistence that he not deviate from where he was instructed to dig.[252]

Cram informed investigators of Gacy's attempts to rape him in 1976 and stated that after he and Gacy had returned to his home after the December 13 search of his property, Gacy had turned pale upon noting a clot of mud on his carpet which he suspected had come from his crawl space. Cram then stated Gacy had grabbed a flashlight and immediately entered the crawl space to look for evidence of digging. When asked whether he had been to the crawl space, Cram replied he had once been asked by Gacy to spread lime down there and had also dug trenches upon Gacy's behest with the explanation they were for drainage pipes.[249] Cram stated these trenches were 2 feet (0.61 m) wide, 6 feet (1.8 m) long and 2 feet (0.61 m) deep—the size of graves.[253]

Verbal confession

On the evening of December 20, Gacy drove to his lawyers' office in Park Ridge to attend a pre-scheduled meeting he had arranged with them, ostensibly to discuss the progress of his civil suit. Upon his arrival, Gacy appeared disheveled and immediately asked for an alcoholic drink, whereupon Sam Amirante fetched a bottle of whiskey from his car. Upon his return, Amirante asked Gacy what he had to discuss with them. Gacy picked up a copy of the Daily Herald from Amirante's desk; he pointed to a front-page article covering the disappearance of Robert Piest and informed his lawyers: "This boy is dead. He's in a river."[254]

Over the following hours, Gacy gave a rambling confession that ran into the early hours of the following morning. He began by informing Amirante and Stevens he had "been the judge ... jury and executioner of many, many people", and that he now wanted to be the same for himself.[255] He stated most of his victims were buried in his crawl space, and others in the Des Plaines River. Gacy dismissed his victims as "male prostitutes", "hustlers" and "liars" to whom he gave "the rope trick", adding that he occasionally awoke to find "dead, strangled kids" on his floor, with their hands cuffed behind their back.[256]

As a result of the alcohol he had consumed, Gacy fell asleep midway through his confession and Amirante immediately arranged a psychiatric appointment for Gacy at 9:00 a.m. that morning. Upon awakening several hours later, Gacy simply shook his head when informed by Amirante he had earlier confessed to killing approximately 30 people, stating: "Well, I can't think about this right now. I've got things to do."[257] Ignoring his lawyers' advice regarding his scheduled appointment, Gacy left their office to attend to the needs of his business.[257]

Gacy later recollected his memories of his final day of freedom as being "hazy", adding that he knew his arrest was inevitable and that, in his final hours of freedom, he intended to visit his friends and say his final farewells.[258] Upon leaving his lawyers' office, Gacy drove to a Shell gas station where, in the course of filling his rental car, he handed a small bag of cannabis to the attendant, Lance Jacobson. Jacobson immediately handed the bag to the surveillance officers, adding that Gacy had told him: "The end is coming (for me). These guys are going to kill me." Gacy then drove to the home of a fellow contractor, Ronald Rhode. Inside Rhode's living room, Gacy hugged Rhode before bursting into tears and saying: "I've been a bad boy. I killed thirty people, give or take a few."[259] Gacy then left Rhode and drove to David Cram's home to meet with Cram and Rossi. As he drove along the expressway, the surveillance officers noted he was holding a rosary to his chin as he prayed while driving.[260]

After talking with Cram and Rossi, Gacy had Cram drive him to a scheduled meeting with Leroy Stevens. As Gacy spoke with his lawyer, Cram informed the officers that Gacy had divulged to himself and Rossi that the previous evening, he had confessed to his lawyers his guilt in over thirty murders. Gacy then had Cram drive him to Maryhill Cemetery, where his father was buried.[261]

As Gacy drove to various locations that morning, police outlined their formal draft of their second search warrant. The purpose of the warrant was specifically to search for the body of Robert Piest in the crawl space. Upon hearing from the surveillance detectives that, in light of his erratic behavior, Gacy may be about to commit suicide, police decided to arrest him upon a charge of possession and distribution of marijuana[262] in order to hold him in custody as the formal request for a second search warrant was presented. At 4:30 p.m. on December 21, the eve of the hearing of Gacy's civil suit, the request for a second search warrant was granted by Judge Marvin J. Peters.[263]

Armed with the signed search warrant, police and evidence technicians drove to Gacy's home. Upon their arrival, officers found that Gacy had unplugged his sump pump and that the crawl space was flooded with water; to clear the water they simply replaced the plug and waited for the water to drain. After it had done so, evidence technician Daniel Genty entered the 28-by-38-foot (8.5 m × 11.6 m) crawl space,[264] crawled to the southwest area, and began digging. Within minutes, he had uncovered putrefied flesh and a human arm bone. Genty immediately shouted to the investigators that they could charge Gacy with murder.[265] Genty added the remark: "I think this place is full of kids."[265]

Arrest and confession

After being informed that the police had found human remains in his crawl space and that he would now face murder charges, Gacy told officers he wanted to "clear the air",[266] adding that he had known his arrest was inevitable since the previous evening, which he had spent on the couch in his lawyers' office.[267]

In the early hours of December 22, 1978, Gacy confessed to police that since 1972, he had committed 25 to 30 murders, all of whom he falsely claimed were of teenage male runaways or male prostitutes, the majority of whom he had buried in his crawl space.[140] He claimed to have only dug five of the victims' graves in this location[268] and had his employees (including Gregory Godzik) dig the remaining trenches so that he would "have graves available".[269]

Some victims Gacy referred to by name, but most names he claimed not to know or remember.[270] He confessed he had buried the body of John Butkovich in his garage.[271] When asked where he drew the inspiration for the two-by-four attached with manacles at either end found at his house, Gacy stated he had been inspired to construct the device from reading about the Houston Mass Murders.[272][lower-alpha 11] In January 1979, he had planned to further conceal the corpses by covering the entire crawl space with concrete.[111]

When specifically questioned about Piest, Gacy confessed to strangling him at his house on the evening of December 11 after luring him there. He also admitted to having slept alongside Piest's body that evening, before disposing of the corpse in the Des Plaines River in the early hours of December 13.[276] The reason he had arrived at the police station in a dirty and disheveled manner in the early hours of December 13 was that he had been in a minor traffic accident en route to his appointment with Des Plaines officers after disposing of Piest's body. In this accident, his vehicle had slid off an ice-covered road, and he had unsuccessfully attempted to free the vehicle himself before the vehicle had to be towed from its location.[277]

To assist officers in their search for the victims buried beneath his house, Gacy drew a rough diagram of his basement upon a phone message sheet to indicate where their bodies were buried.[278]

Search for victims

On December 22 police took Gacy to his house, where he marked his garage floor with paint to show where he had buried Butkovich's body. They then drove to the spot on the I-55 bridge from which he had thrown the bodies of Piest and four others.[204][279]

By December 29, twenty-six bodies had been found in the crawl space, and one beneath the garage.[280] Operations were suspended due to the Chicago Blizzard of 1979, but resumed in March despite Gacy's insistence that all the buried victims had been found.[281][58]

On March 9, a body was found buried close to a barbecue in the backyard, and on March 16 another was found beneath the dining room floor.[282][282] In April 1979, Gacy's vacant house was demolished.[283]

Three additional bodies, which had been found in the nearby Des Plaines River between June and December 1978, were also confirmed to have been victims of Gacy.[284]

Several bodies unearthed at Gacy's property were found with plastic bags over their heads or upper torsos.[lower-alpha 12] Some bodies were found with the ligature used to strangle them still knotted around their necks. In other instances, cloth gags were found lodged deep down the victims' throats, leading the medical examiner to conclude that 12 victims died not of strangulation, but of asphyxiation.[94] In some cases, bodies were found with foreign objects such as prescription bottles lodged into their pelvic region, the position of which indicated the items had been thrust into the victims' anus.[286] All the victims discovered at 8213 Summerdale were in an advanced state of decomposition, and the medical examiner chiefly relied upon dental records to facilitate the identification of the remains.[287]

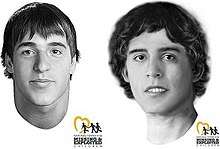

Two victims were identified because of their known connection to Gacy through PDM.[288] Most identifications were facilitated with the assistance of X-ray charts.[289] Identifications were supported via personal artifacts being found at 8213 Summerdale: one victim, 19-year-old David Talsma, was identified via comparison of radiology records of a healed fracture of the left scapula matching distress evident upon the 17th skeleton recovered from Gacy's property.[290] Timothy O'Rourke was last heard mentioning that a contractor had offered him a job.[204] Of Gacy's identified victims, the youngest were Samuel Stapleton and Michael Marino, both 14; the oldest was Russell Nelson, who was 21. Six victims have never been identified.[291]

On April 9, 1979, a decomposed body was discovered entangled in exposed roots on the edge of the Des Plaines River in Grundy County.[292] The body was identified via dental records as being that of Robert Piest. A subsequent autopsy revealed that three wads of "paper-like material" had been shoved down his throat while he was alive,[293] causing him to die of suffocation.[294]

Trial

Gacy was brought to trial on February 6, 1980, charged with 33 murders.[295] He was tried in Cook County, Illinois, before Judge Louis Garippo; the jury was selected from Rockford because of significant press coverage in Cook County.[296]

At the request of his defense counsel, Gacy spent over three hundred hours in the year before his trial with the doctors at the Menard Correctional Center. He underwent a variety of psychological tests before a panel of psychiatrists to determine whether he was mentally competent to stand trial.[297][298]

Gacy had attempted to convince the doctors that he suffered from a multiple personality disorder.[299] He claimed to have four personalities: the workaholic contractor, the clown, the active politician, and his fourth personality was a policeman called Jack Hanley, whom he referred to as "Bad Jack". When Gacy had confessed to police, he claimed to be relaying the crimes of Jack, who detested homosexuality.[300] His lawyers opted to have Gacy plead not guilty by reason of insanity to the charges against him. Presenting Gacy as a Jekyll and Hyde character,[301] the defense produced several psychiatric experts who had examined Gacy the previous year to testify to their findings.[302] Three psychiatric experts at Gacy's trial testified they found Gacy to be a paranoid schizophrenic with a multiple personality disorder.[303][58]

The prosecutors presented a case that indicated Gacy was sane and fully in control of his actions.[282] To support this contention, they produced several witnesses to testify to the premeditation of Gacy's actions and the efforts he went to in order to escape detection. Those doctors refuted the defense doctors' claims of multiple personality and insanity. Cram and Rossi both confessed that Gacy had made them dig trenches in his crawl space. Cram testified that in August 1977, Gacy had marked a location in the crawl space with sticks and told him to dig a drainage trench.[104][252][177]

Immediately after Cram had completed his testimony, Rossi testified for the state. When asked where he had dug in the crawl space, Rossi turned to a diagram of Gacy's home on display in the courtroom. This diagram showed where the bodies were found in the crawl space and elsewhere on the property. Rossi pointed to the location of the remains of an unidentified victim known as "Body 13".[177] Rossi stated he had not dug any other trenches, but—at Gacy's request—had supervised other PDM employees digging trenches in the crawl space.[252]

Both Rossi and Cram also testified that Gacy periodically looked into the crawl space to ensure they and other employees ordered to dig these trenches did not deviate from the precise locations he had marked.[304]

On February 18 Robert Stein,[305] the Cook County medical examiner who supervised the exhumations, testified that all the bodies were "markedly decomposed [and] putrefied",[306] and that of all the autopsies he performed, thirteen victims had died of asphyxiation, six of ligature strangulation, one of multiple stab wounds to the chest,[115] and ten in undetermined ways.[307][lower-alpha 13] When Gacy's defense team suggested that all 33 deaths were accidental (by erotic asphyxia), Stein called this highly improbable.[308][309]

Jeffrey Rignall testified on behalf of the defense on February 21.[310] Recounting his ordeal, Rignall wept repeatedly while describing Gacy's torture of him in March 1978. Asked whether Gacy appreciated the criminality of his actions, Rignall said he believed that Gacy was unable to conform his actions to the law's expectations because of the "beastly and animalistic ways he attacked me".[311] During specific cross-examination relating to the torture, Rignall vomited and was excused from further testimony.[312]

On February 29, Donald Voorhees, whom Gacy had sexually assaulted in 1967, testified to his ordeal at Gacy's hands and Gacy's attempts to dissuade him from testifying by paying another youth to spray Mace in his face and beat him.[313] Voorhees felt unable to testify, but did briefly attempt to do so, before being asked to step down.[313]

Robert Donnelly testified the week after Voorhees, recounting his ordeal at Gacy's hands in December 1977. Donnelly was visibly distressed as he recollected the abuse he endured at Gacy's hands and came close to breaking down on several occasions. As Donnelly testified, Gacy repeatedly laughed at him,[314] but Donnelly finished his testimony. During Donnelly's cross-examination, one of Gacy's defense attorneys, Robert Motta, attempted to discredit his testimony, but Donnelly did not waver from his testimony of what had occurred.[315]

During the fifth week of the trial, Gacy wrote a personal letter to Judge Garippo requesting a mistrial[316] on a number of bases, including that he did not approve his lawyers' insanity plea approach; that his lawyers had not allowed him to take the witness stand (as he had desired to do); that his defense had not called enough witnesses, and that the police were lying about statements he had purportedly made to detectives after his arrest and that, in any event, the statements were "self-serving" for use by the prosecution.[317] Judge Garippo addressed Gacy's letter by informing him that under the law he had the choice as to whether he wished to testify, and he was free to indicate as much to the judge if he wished to do so.[318]

Closing arguments

On March 11, final arguments from both prosecution and defense attorneys began, with the arguments concluding on the following day. Prosecuting attorney Terry Sullivan argued first, outlining Gacy's history of abusing youths, the testimony of his efforts to avoid detection and describing Gacy's surviving victims—Voorhees and Donnelly—as "living dead".[319] Referring to Gacy as the "worst of all murderers",[320] Sullivan stated: "John Gacy has accounted for more human devastation than many earthly catastrophes, but one must tremble. I tremble when thinking about just how close he came to getting away with it all."[319]

After the state's four-hour closing, counsel Sam Amirante argued for the defense. Amirante argued against the testimony delivered by the doctors who had testified for the prosecution, repeatedly citing the testimony of the four psychiatrists and psychologists who had testified on behalf of the defense.[321] Amirante also accused Sullivan of scarcely referring to the evidence presented throughout the trial in his own closing argument, and of arousing hatred against his client. The defense lawyer attempted to portray Gacy as a "man driven by compulsions he was unable to control".[322]

In support of these arguments, the defense counsel repeatedly referred to the testimony of the doctors who had appeared for the defense, in addition to the testimony of defense witnesses such as Jeffrey Rignall and Gacy's former business associate Mickel Reed—both of whom had testified to their belief that Gacy had been unable to control his actions.[323] Amirante then urged the jury to put aside any prejudice they held against his client, and requested they deliver a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity, adding that the psychology of Gacy's behavior would be of benefit to scientific research and that the psychology of his mind should be studied.[324]

On the morning of March 12,[325] William Kunkle continued to argue for the prosecution. Kunkle referred to the defense's contention of insanity as "a sham", arguing that the facts of the case demonstrated Gacy's ability to think logically and control his actions. Kunkle also referred to the testimony of a doctor who had examined Gacy in 1968. This doctor had diagnosed Gacy as an antisocial personality, capable of committing crimes without remorse. Kunkle indicated that had the recommendations of this doctor been heeded, Gacy would have not been freed.[326]

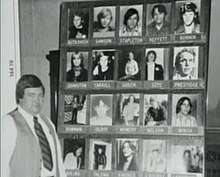

At the close of his argument, Kunkle pulled each of the 22 photos of Gacy's identified victims off a board displaying the images and asked the jury not to show sympathy but to "show justice". Kunkle then asked the jury to "show the same sympathy this man showed when he took these lives and put them there!"[326] before throwing the stack of photos into the opening of the trap door of Gacy's crawl space, which had been introduced as evidence and was on display in the courtroom. After Kunkle had finished his testimony, the jury retired to consider their verdict.[327]

The jury deliberated for less than two hours[328] and found Gacy guilty of the thirty-three charges of murder for which he had been brought to trial; he was also found guilty of sexual assault and taking indecent liberties with a child; both convictions in reference to Robert Piest.[327][329] The conviction for 33 murders was then the largest number of murders charged to one individual in United States history.[128]

In the sentencing phase of the trial, the jury deliberated for more than two hours before sentencing Gacy to death for each murder committed after the Illinois statute on capital punishment came into effect in June 1977.[330][331][332] Execution was initially set for June 2, 1980.[333]

Death row

Upon being sentenced, Gacy was transferred to the Menard Correctional Center in Chester, Illinois, where he remained incarcerated on death row for 14 years.[334]

Isolated in his prison cell, Gacy began to paint. The subjects Gacy painted varied, although many were of clowns, some of which depicted himself as "Pogo". Many of his paintings have been displayed at exhibitions;[335][336] others have been sold at various auctions, with individual prices ranging between $200 and $20,000.[337] Although Gacy was permitted to earn money from the sale of his paintings until 1985, he claimed his artwork was intended "to bring joy into people's lives".[338]

On February 15, 1983, Gacy was stabbed in the arm by Henry Brisbon, a fellow death row inmate known as the I-57 killer. At the time of this attack, Gacy had been participating in a voluntary work program when Brisbon ran towards him and stabbed him once in the upper arm with a sharpened wire. A second death row inmate injured in the attack, William Jones, received a superficial stab wound to the head. Both received treatment in the prison hospital for their wounds.[339]

Appeals

After his incarceration, Gacy read numerous law books and filed voluminous motions and appeals, although he did not prevail in any. Gacy's appeals related to issues such as the validity of the first search warrant granted to Des Plaines police on December 13, 1978, and his objection to his lawyers' insanity plea defense at his trial.[340] Gacy also contended that, although he held "some knowledge" of five of the murders (those of McCoy, Butkovich, Godzik, Szyc and Piest),[33] the other 28 murders had been committed by employees who were in possession of keys to his house while he was away on business trips.

In mid-1984, the Supreme Court of Illinois upheld Gacy's conviction and ordered that he be executed by lethal injection on November 14.[338] Gacy filed an appeal against this decision, which was denied by the Supreme Court of the United States on March 4, 1985. The following year, Gacy filed a further post-conviction petition, seeking a new trial. His then-defense lawyer, Richard Kling, argued that Gacy had been provided with ineffective legal counsel at his 1980 trial. This post-conviction petition was dismissed on September 11, 1986.[341]

The 1985 decision that he be executed was again appealed by Gacy, although his conviction was again upheld on September 29, 1988, with the Illinois Supreme Court setting a renewed execution date of January 11, 1989.[342]

After Gacy's final appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied in October 1993, the Illinois Supreme Court formally set an execution date for May 10, 1994.[343]

Execution

On the morning of May 9, 1994, Gacy was transferred from the Menard Correctional Center to Stateville Correctional Center in Crest Hill to be executed. That afternoon, he was allowed a private picnic on the prison grounds with his family. For his last meal, Gacy ordered a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken, a dozen fried shrimp, french fries, fresh strawberries, and a Diet Coke.[344] That evening, he observed prayer with a Catholic priest before being escorted to the Stateville execution chamber to receive a lethal injection.[345]