Homo habilis

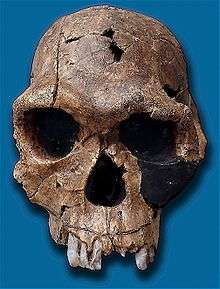

Homo habilis is an archaic species of Stone Age human which lived between roughly 2.1 and 1.5 million years ago (mya), during the Early Pleistocene.[1] The species was first discovered by anthropologists Mary and Louis Leakey at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania in 1955, associated with the Oldowan stone tool industry.[2]

| Homo habilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of KNM-ER 1813 at the Naturmuseum Senckenberg, Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. habilis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo habilis Leakey et al., 1964 | |

H. habilis is considered to be intermediate between Australopithecus afarensis and H. erectus. It has been suggested reclassifying the species as Australopithecus habilis, as one of the main arguments for its classification into Homo was the now outdated idea that it was the earliest human ancestor to use stone tools. H. habilis likely used tools for butchering meat which it scavenged from more fearsome carnivores.

H. habilis coexisted with other early hominins, such as the robust Paranthropus and Homo erectus.

Taxonomy

Since its discovery, it has been argued that Homo habilis should be reclassified as Australopithecus habilis,[3][4] on the basis of small size and some rather primitive attributes .[5][6][7]

Louis and Mary Leakey first discovered H. habilis in 1955. It was first formally described by paleoanthropologists Mr. Leakey, Phillip V. Tobias, and John R. Napier on the basis of a jawbone with some teeth, parietal bone fragments, and hand bones of the 1.75 Ma juvenile OH 7. The species name habilis was given on recommendation by South African anthropologist Raymond Dart, and is Latin for "able, handy, mentally skillful, vigorous".[8]

The earliest specimen, LD 350-1, dating to 2.8 million years ago, was argued to be intermediate between Australopithecus and H. habilis.[9] The fossil was claimed as the earliest evidence of the genus Homo known to date. The individual in question lived just after a major climate shift in the region, when forests and waterways were rapidly replaced by arid savannah.[10]

Homo habilis is considered to be the ancestor of the more gracile and sophisticated H. ergaster (the African H. erectus). Debates continue over whether all of the known fossils are properly attributed to the species, and some paleoanthropologists regard the taxon as invalid, made up of various specimens of Australopithecus and Homo.[11] Since H. habilis and H. erectus coexisted, an isolated subpopulation of H. habilis may have evolved into H. erectus, and other subgroups remained as unchanged H. habilis until their extinction.[12]

The discoverers of the Georgian Dmanisi skull suggested that all the contemporary groups of early Homo in Africa–including H. ergaster, H. habilis, and H. rudolfensis–are all different stages in the evolution of H. erectus, making them a chronospecies.[13][14][15]

Description

H. habilis brain size has been shown to range from 550 cm3 (34 cu in) to 687 cm3 (41.9 cu in), rather than from 363 cm3 (22.2 cu in) to 600 cm3 (37 cu in) as previously thought.[4][16] A virtual reconstruction published in 2015 estimated the endocranial volume at between 729 ml (25.7 imp fl oz; 24.7 US fl oz) and 824 ml (29.0 imp fl oz; 27.9 US fl oz), larger than any previously published value.[17] Their average brain size was about 45% greater than Australopithecus, and 25% greater than Paranthropus. H. habilis appears to have had an expanded cerebrum, unlike australopithecines, specifically the frontal and parietal lobes which govern speech in modern humans.[18] H. habilis had a less protruding face (less prognathism) than australopithecines.

H. habilis was smaller than modern humans, on average standing no more than 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in). It had proportionally longer legs than australopithecines, and was more similar to humans in this aspect.[19] However, the arms were more chimp-like and adapted for swinging and load bearing, unlike A. afarensis and other Homo.[20][21][22][23]

A 2018 study of the anatomy of A. sediba found that A. sediba is distinct from but closely related to both Homo habilis and Australopithecus africanus.[24]

Culture

H. habilis is associated with the Lower Paleolithic Olduwan stone tool industry at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania and Lake Turkana, Kenya. They likely used these tools to butcher and skin animals.[25] It was previously thought H. habilis was the first human ancestor to have used stone tools, but australopithecines have also been associated with tools, such as the 2.6 Ma A. garhi,[26] the 3.3 Ma Lomekwi stone tool industry,[27] and some evidence of butchering from about 3.4 mya.[28]

It is thought H. habilis used tools primarily for scavenging, such as cleaving meat off carrion, rather than defense or hunting (scavenger hypothesis). They may have been confrontational scavengers, stealing kills from the smaller predators of their environment such as jackals or cheetahs.[29] Fruit was likely also an important dietary component, indicated by dental erosion consistent with repetitive exposure to acidity.[30]

Based on dental microwear-texture analysis, H. habilis (like other early Homo) likely did not regularly consume tough foods. Microwear-texture complexity is, on average, somewhere between that of tough-food feeders and leaf feeders (folivores),[31] and point to an increasingly generalized and omnivorous diet.[32]

It is generally thought that the intelligence and social organization of H. habilis were more sophisticated than typical australopithecines or chimpanzees. H. habilis' proportionally longer legs may indicate long distance travel.[19]

Paleoecology

H. habilis and other hominins were likely predated upon by the large carnivores of the time, such as the hunting hyena Chasmaporthetes nitidula, the leopard, the saber-toothed cats Dinofelis and Megantereon,[33] and possibly crocodiles such as Crocodylus anthropophagus.[34]

Homo habilis coexisted with other hominins, namely Paranthropus. H. habilis may have outlived Paranthropus due to advanced tool use.[35] H. habilis may also have coexisted with H. erectus about 1.8 mya.[36][37]

See also

- List of fossil sites

- List of human evolution fossils

- KNM-ER 1805

- KNM-ER 1813

- OH 24

Notes

- Friedemann Schrenk, Ottmar Kullmer, Timothy Bromage, "The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils", chapter 9 in: Winfried Henke, Ian Tattersall (eds.), Handbook of Paleoanthropology, 2007, pp. 1611–1631, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_52

- Wood, Bernard "Fifty Years After Homo habilis", Nature. 3 April 2014. pp. 31–33.

- Wood and Richmond; Richmond, BG (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270. p. 41: "A recent reassessment of cladistic and functional evidence concluded that there are few, if any, grounds for retaining H. habilis in Homo, and recommended that the material be transferred (or, for some, returned) to Australopithecus (Wood & Collard, 1999)."

- Australian Museum: http://australianmuseum.net.au/Homo-habilis.

- Miller J. M. A. (2000). "Craniofacial variation in Homo habilis: an analysis of the evidence for multiple species". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 112 (1): 103–128. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200005)112:1<103::AID-AJPA10>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 10766947.

- Tobias, P. V. (1991). "The species Homo habilis: example of a premature discovery". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 28 (3–4): 371–380. JSTOR 23735461.

- Collard, Mark; Wood, Bernard (2015). "Defining the Genus Homo". Handbook of Paleoanthropology. pp. 2107–2144. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39979-4_51. ISBN 978-3-642-39978-7.

- Leakey, L.; Tobias, P. V.; Napier, J. R. (1964). "A New Species of the Genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge" (PDF). Nature. 202 (4927): 7–9. doi:10.1038/202007a0.

- Villmoare B., Kimbel H., Seyoum C., Campisano C., DiMaggio E., Rowan J., Braun D., Arrowsmith J., Reed K. (2015). Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia. Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343

- "Vertebrate fossils record a faunal turnover indicative of more open and probable arid habitats than those reconstructed earlier in this region, in broad agreement with hypotheses addressing the role of environmental forcing in hominin evolution at this time." DiMaggio E. N.; Campisano, C. J.; Rowan, J.; Dupont-Nivet, G.; Deino, A. L.; et al. (2015). "Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1355–9. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1415. PMID 25739409.

- Tattersall, I., & Schwartz, J. H., Extinct Humans, Westview Press, New York, 2001, p. 111.

- F. Spoor; M. G. Leakey; P. N. Gathogo; F. H. Brown; S. C. Antón; I. McDougall; C. Kiarie; F. K. Manthi; L. N. Leakey (2007-08-09). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323.

A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an anagenetic relationship with H. erectus unlikely

- Margvelashvili, Ann; Zollikofer, Christoph P. E.; Lordkipanidze, David; Peltomäki, Timo; León, Marcia S. Ponce de (2013-10-02). "Tooth wear and dentoalveolar remodeling are key factors of morphological variation in the Dmanisi mandibles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (43): 17278–83. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11017278M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316052110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3808665. PMID 24101504.

- Lordkipanidze, David; Ponce de León, Marcia S.; Margvelashvili, Ann; Rak, Yoel; Rightmire, G. Philip; Vekua, Abesalom; Zollikofer, Christoph P. E. (2013-10-18). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo". Science. 342 (6156): 326–331. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..326L. doi:10.1126/science.1238484. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24136960.

- Margvelashvili, Ann; Zollikofer, Christoph P. E.; Lordkipanidze, David; Peltomäki, Timo; León, Marcia S. Ponce de (2013-10-02). "Tooth wear and dentoalveolar remodeling are key factors of morphological variation in the Dmanisi mandibles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (43): 17278–83. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11017278M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316052110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3808665. PMID 24101504.

- Brown, Graham; Fairfax, Stephanie; Sarao, Nidhi. Tree of Life Web Project: Human Evolution. Link: http://tolweb.org/treehouses/?treehouse_id=3710.

- F. Spoor; P. Gunz; S. Neubauer; S. Stelzer; N. Scott; A. Kwekason; M. C. Dean (2015). "Reconstructed Homo habilis type OH 7 suggests deep-rooted species diversity in early Homo". Nature. 519 (7541): 83–86. doi:10.1038/nature14224. PMID 25739632.

- Tobias, P. V. (1987). "The brain of Homo habilis: A new level of organization in cerebral evolution". Journal of Human Evolution. 16 (7–8): 741–761. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(87)90022-4.

- Haeusler, M.; McHenry, H. M. (2004). "Body Proportions of Homo Habilis". Journal of Human Evolution. 46 (4): 433–465. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.01.004.

- Haeusler, M.; McHenry, H. (2007). "Evolutionary reversals of limb proportions in early hominids? evidence from KNM-ER 3735 (Homo habilis)". Journal of Human Evolution. 53 (4): 385–405. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.06.001.

- Donald C. Johanson; Fidelis T. Masao; Gerald G. Eck; Tim D. White; Robert C. Walter; William H. Kimbel; Berhane Asfaw; Paul Manega; Prosper Ndessokia; Gen Suwa (21 May 1987). "New partial skeleton of Homo habilis from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania". Nature. 327 (6119): 205–209. doi:10.1038/327205a0. PMID 3106831.

- "Relative Limb Strength and Locomotion in Homo habilis", Ruff, Christopher, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 138:90–100 (2009)

- Wood, Bernard (21 May 1987). "Who is the 'real' Homo habilis?". Nature. 327 (6119): 187–188. doi:10.1038/327187a0. PMID 3106828.

- Jeremy M. DeSilva (ed.), Special Issue on Australopithecus sediba, PaleoAnthropology (2018), doi:10.4207/PA.2018.ART111.

- Pollard, Elizabeth (2014-12-16). Worlds Together, Worlds Apart. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.CS1 maint: location (link)

- De Heinzelin, J; Clark, JD; White, T; Hart, W; Renne, P; Woldegabriel, G; Beyene, Y; Vrba, E (1999). "Environment and behavior of 2.5-million-year-old Bouri hominids" (PDF). Science. 284 (5414): 625–9. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.625. PMID 10213682.

- Harmand, S.; Lewis, J. E.; Feibel, C. S.; et al. (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. doi:10.1038/nature14464.

- McPherron, Shannon P.; Zeresenay Alemseged; Curtis W. Marean; Jonathan G. Wynn; Denne Reed; Denis Geraads; Rene Bobe; Hamdallah A. Bearat (2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466 (7308): 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305.

- Cavallo, J. A.; Blumenschine, R. J. (1989). "Tree-stored leopard kills: expanding the hominid scavenging niche". Journal of Human Evolution. 18 (4): 393–399. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(89)90038-9.

- Peuch, P.-F. (1984). "Acidic-Food Choice in Homo habilis at Olduvai". Current Anthropology. 25 (3): 349–350. doi:10.1086/203146.

- Ungar, Peter (9 February 2012). "Dental Evidence for the Reconstruction of Diet in African Early Homo". Current Anthropology. 53: S318–S329. doi:10.1086/666700.

- Ungar, Peter; Grine, Frederick; Teaford, Mark; Zaatari, Sireen (1 January 2006). "Dental Microwear and Diets of African Early Homo". Journal of Human Evolution. 50 (1): 78–95. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.08.007. PMID 16226788.

- Lee-Thorp, J.; Thackeray, J. F.; der Merwe, N. V. (2000). "The hunters and the hunted revisited". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (6): 565–576. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0436.

- Christopher A. Brochu, Jackson Njau, Robert J. Blumenschine and Llewellyn D. Densmore (2010). "A New Horned Crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene Hominid Sites at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania". PLoS ONE. 5 (2): e9333. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9333B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009333. PMC 2827537. PMID 20195356.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Urquhart, James (8 August 2007). "Finds test human origins theory". BBC News. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- Leakey, M. G.; Spoor, F.; Dean, M. C.; et al. (2012). "New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo". Nature. 448 (7410): 201–204. doi:10.1038/nature11322. PMID 22874966.

- F. Spoor; M. G. Leakey; P. N. Gathogo; F. H. Brown; S. C. Antón; I. McDougall; C. Kiarie; F. K. Manthi; L. N. Leakey (2007-08-09). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323.

References

- Early Humans (Roy A. Gallant)/Copyright 2000 ISBN 0-7614-0960-2

- The Making of Mankind, Richard E. Leakey, Elsevier-Dutton Publishing Company, Inc., Copyright 1981, ISBN 0-525-15055-2, LC Catalog Number 81-664544.

- Fifty Years After Homo habilis (PDF), Bernard Wood, Nature, Vol. 508, (3 April 2014)

- Relative Limb Strength and Locomotion in Homo habilis (PDF), Christopher Ruff, American Journal of Physical Anthropology 138:90–100 (2009)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo habilis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Homo habilis |

- Reconstructions of H. habilis by John Gurche

- Archaeology Info

- Homo habilis – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- BBC:Food for thought

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).