Homo floresiensis

Homo floresiensis ("Flores Man"; nicknamed "hobbit"[2]) is a small species of archaic human which inhabited the island of Flores, Indonesia, until the arrival of modern humans about 50,000 years ago.

| Homo floresiensis | |

|---|---|

| |

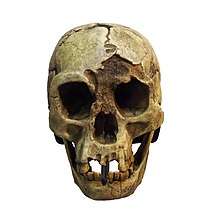

| H. floresiensis skull, Cantonal Museum of Geology, Switzerland | |

| Scientific classification (disputed) | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. floresiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo floresiensis Brown et al., 2004 | |

| Flores in Indonesia, shown highlighted in red | |

The remains of an individual who would have stood about 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) in height were discovered in 2003 at Liang Bua on the island of Flores in Indonesia. Partial skeletons of nine individuals have been recovered, including one complete skull, referred to as "LB1".[3][4] These remains have been the subject of intense research to determine whether they represent a species distinct from modern humans;[5] the dominant consensus is that these remains do represent a distinct species due to genetic and anatomical differences.[6]

This hominin had originally been considered remarkable for its survival until relatively recent times, only 12,000 years ago.[7] However, more extensive stratigraphic and chronological work has pushed the dating of the most recent evidence of its existence back to 50,000 years ago.[8][9][10] The Homo floresiensis skeletal material is now dated from 60,000 to 100,000 years ago; stone tools recovered alongside the skeletal remains were from archaeological horizons ranging from 50,000 to 190,000 years ago.[1]

Specimens

Discovery

The first specimens were discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores in 2003 by a joint Australian-Indonesian team of archaeologists looking for evidence of the original human migration of modern humans from Asia to Australia.[3][7] They instead recovered a nearly complete, small-statured skeleton, LB1, in Liang Bua Cave, and subsequent excavations recovered seven additional skeletons, initially dated from 38,000 to 13,000 years ago.[4] LB1 is a fairly complete skeleton, including a nearly complete skull, which belonged to a 30-year-old woman, and has been nicknamed "Little Lady of Flores" or "Flo".[3][11] An arm bone provisionally assigned to H. floresiensis is about 74,000 years old. The specimens are not fossilized and have been described as having "...the consistency of wet blotting paper." Once exposed, the bones had to be left to dry before they could be dug up.[12][13]

Stone implements of a size considered appropriate to these small humans are also widely present in the cave. The implements are at horizons initially dated to 95,000 to 13,000 years ago.[4] Modern humans reached the region by around 50,000 years ago, by which time H. floresiensis is thought to have gone extinct.[1] Comparisons of the stone artefacts with those made by modern humans in East Timor indicate many technological similarities.[14]

Scandal over specimen damage

In early December 2004, Indonesian paleoanthropologist Teuku Jacob removed most of the remains from their repository, Jakarta's National Research Centre of Archaeology, with the permission of only one of the project team's directors and kept them for three months.[15][16][17][18] Some scientists expressed the fear that important scientific evidence would be sequestered by a small group of scientists who neither allowed access by other scientists nor published their own research. Jacob returned the remains on 23 February 2005 with portions severely damaged[19] and missing two leg bones[20] to the worldwide consternation of his peers.

Reports noted the condition of the returned remains, "... [including] long, deep cuts marking the lower edge of the Hobbit's jaw on both sides, said to be caused by a knife used to cut away the rubber mould ... the chin of a second Hobbit jaw was snapped off and glued back together. Whoever was responsible misaligned the pieces and put them at an incorrect angle ... The pelvis was smashed, destroying details that reveal body shape, gait and evolutionary history."[21] and causing the discovery team leader Morwood to remark, "It's sickening; Jacob was greedy and acted totally irresponsibly."[19]

Jacob, however, denied any wrongdoing. He stated that the damages occurred during transport from Yogyakarta back to Jakarta[21] despite the physical evidence to the contrary that the jawbone had been broken while making a mould of the bones.[19][22]

In 2005, Indonesian officials forbade access to the cave. Some news media, such as the BBC, expressed the opinion that the restriction was to protect Jacob, who was considered "Indonesia's king of palaeoanthropology," from being proven wrong. Scientists were allowed to return to the cave in 2007, shortly after Jacob's death.[21]

Classification

Phylogeny

The discoverers proposed that a variety of features, both primitive and derived, identify these individuals as belonging to a new species, H. floresiensis.[3][7] Based on previous date estimates, the discoverers also proposed that H. floresiensis lived contemporaneously with modern humans on Flores.[23] Before publication, the discoverers were considering placing LB1 into her own genus, Sundanthropus floresianus ("Sunda human from Flores"), but reviewers of the article recommended that, despite her size, she should be placed in the genus Homo.[24]

Two orthopedic studies published in 2007 reported that the wrist bones were more similar to those of chimps and Australopithecus than to modern humans.[25] However, another 2007 study of the bones and joints of the arm, shoulder, and lower limbs also concluded that H. floresiensis was more similar to early humans and other apes than modern humans.[26] A 2009 cladistic analysis concluded H. floresiensis branched off very early from the modern human line, either shortly before or shortly after the evolution of H. habilis 1.96–1.66 million years ago.[27] In 2009, American anthropologist William Jungers and colleagues found that the foot of H. floresiensis has several primitive characters, and that they could be the descendants of a species much earlier than H. erectus.[28] A 2015 Bayesian analysis found greatest similarity with Australopithecus sediba, Homo habilis and the primitive H. erectus georgicus, raising the possibility that the ancestors of H. floresiensis left Africa before the appearance of H. erectus, and were possibly even the first hominins to do so.[29] However, H. floresiensis has several dental similarities to H. erectus, which could mean H. erectus was the ancestor species.[30]

Their ancestors may have reached the island by 1 million years ago.[31][32] In 2016, fossil teeth and a partial jaw from hominins assumed to be ancestral to H. floresiensis were discovered[33] at Mata Menge, about 74 km (46 mi) from Liang Bua. They date to about 700,000 years ago[34] and are noted by Australian archaeologist Gerrit van den Bergh for being even smaller than the later fossils. Based on these, he suggested that H. floresiensis derived from a population of H. erectus and rapidly shrank.[35] A phylogenetic analysis published in 2017 suggests that H. floresiensis was descended from the same (presumably australopithecine) ancestor as H. habilis, making it a sister taxon to H. habilis. On the basis of this classification, H. floresiensis is hypothesized to represent a hitherto unknown and very early migration out of Africa.[6] A similar conclusion was suggested in a 2018 study dating stone artefacts found at Shangchen, central China, to 2.1 million years ago.[36]

Evolutionary tree according to a 2019 study:[37]

| Hominini |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DNA extraction attempt

In 2006, two teams attempted to extract DNA from a tooth discovered in 2003, but both teams were unsuccessful. It has been suggested that this happened because the dentine was targeted; new research suggests that the cementum has higher concentrations of DNA. Moreover, the heat generated by the high speed of the drill bit may have denatured the DNA.[38]

Congenital disorder hypotheses

The small brain size of H. floresiensis at 417 cc has prompted hypotheses that the specimens were simply H. sapiens with a birth defect, rather than the result of neurological reorganisation.[39]

- Microcephaly

Prior to Jacob's removal of the fossils, American neuroanthropologist Dean Falk and her colleagues performed a CT scan of the LB1 skull and a virtual endocast, and concluded that the brainpan was neither that of a pygmy nor an individual with a malformed skull and brain.[40] In response, American neurologist Jochen Weber and colleagues compared the computer model skull with microcephalic human skulls, and found that the skull size of LB1 falls in the middle of the size range of the human samples, and is not inconsistent with microcephaly.[41][42] In 2006, American biologist Robert Martin and colleagues also concluded that the skull was probably microcephalic, arguing that the brain is far too small to be a separate dwarf species; he said that, if it were, the 400-cubic-centimeter brain would indicate a creature only one foot in height, one-third the size of the discovered skeleton.[43] A 2006 study stated that LB1 probably descended from a pygmy population of modern humans, but herself shows signs of microcephaly, and other specimens from the cave show small stature but not microcephaly.[44]

In 2005, the original discoverers of H. floresiensis, after unearthing more specimens, countered that the skeptics had mistakenly attributed the height of H. floresiensis to microcephaly.[4] Falk stated that Martin's assertions were unsubstantiated.[45] In 2006, Australian palaeoanthropologist Debbie Argue and colleagues also concluded that the finds are indeed a new species.[46] In 2007, Falk found that H. floresiensis brains were similar in shape to modern humans, and the frontal and temporal lobes were well-developed, which would not have been the case were they microcephalic.[47] In 2008, Greek palaeontologist George Lyras and colleagues said that LB1 falls outside the range of variation for human microcephalic skulls.[48] However, a 2013 comparison of the LB1 endocast to a set of 100 normocephalic and 17 microcephalic endocasts showed that there is a wide variation in microcephalic brain shape ratios and that in these ratios the group as such is not clearly distinct from normocephalics. The LB1 brain shape nevertheless aligns slightly better with the microcephalic sample, with the shape at the extreme edge of the normocephalic group.[49] A 2016 pathological analysis of LB1's skull revealed no pathologies nor evidence of microcephaly, and concluded that LB1 is a separate species.[50]

- Laron syndrome

A 2007 study postulated that the skeletons were humans who suffered from Laron syndrome, which was first reported in 1966, and is most common in inbreeding situations, which may have been the case on the small island. It causes a short stature and small skull, and many conditions seen in Laron syndrome patients are also exhibited in H. floresiensis. The estimated height of LB1 is at the lower end of the average for afflicted human women, but the endocranial volume is much smaller than anything exhibited in Laron syndrome patients. However, only DNA can prove this,[51]

- Endemic cretinism

In 2008 Australian researcher Peter Obendorf—who studies endemic cretinism—and colleagues suggested that LB1 and LB6 suffered from myxoedematous (ME) endemic cretinism resulting from congenital hypothyroidism (a non-functioning thyroid), and that they were part of an affected population of H. sapiens on the island.[52] Cretinism, caused by iodine deficiency, is expressed by small bodies and reduced brain size (but ME causes less motor and mental disablement than other forms of cretinism), and is a form of dwarfism still found in the local Indonesian population. They said that various features of H. floresiensis are diagnostic characteristics, such as enlarged pituitary fossa, unusually straight and untwisted humeral heads, relatively thick limbs, double rooted premolar, and primitive wrist morphology.[52]

However, Falk's scans of LB1's pituitary fossa show that it is not larger than usual. Also, in 2009, anthropologists Colin Groves and Catharine FitzGerald compared the Flores bones with those of ten people who had had cretinism, and found no overlap.[53][54] Obendorf and colleagues rejected Groves and FitzGerald's argument the following year.[55] A 2012 study similar to Groves and FitzGeralds' also found no evidence of cretinism.[56]

- Down syndrome

In 2014, physical anthropologist Maciej Henneberg and colleagues claimed that LB1 suffered from Down syndrome, and that the remains of other individuals at the Flores site were merely normal modern humans.[57] However, there a number of characteristics shared by both LB1 and LB6 as well as other known early humans and absent in H. sapiens, such as the lack of a chin.[58] In 2016, a comparative study concluded that LB1 did not exhibit a sufficient number of Down syndrome characteristics to support a diagnoses.[59]

Anatomy

The most important and obvious identifying features of H. floresiensis are its small body and small cranial capacity. Brown and Morwood also identified a number of additional, less obvious features that might distinguish LB1 from modern H. sapiens, including the form of the teeth, the absence of a chin, and the lesser angle in the head of the humerus (upper arm bone). Each of these putative distinguishing features has been heavily scrutinized by the scientific community, with different research groups reaching differing conclusions as to whether these features support the original designation of a new species,[46] or whether they identify LB1 as a severely pathological H. sapiens.[44] A 2015 study of the dental morphology of 40 teeth of H. floresiensis compared to 450 teeth of living and extinct human species, states that they had "primitive canine-premolar and advanced molar morphologies," which is unique among hominins.[30]

The discovery of additional partial skeletons[4] has verified the existence of some features found in LB1, such as the lack of a chin, but Jacob and other research teams argue that these features do not distinguish LB1 from local modern humans.[44] Lyras et al. have asserted, based on 3D-morphometrics, that the skull of LB1 differs significantly from all H. sapiens skulls, including those of small-bodied individuals and microcephalics, and is more similar to the skull of Homo erectus.[48] Ian Tattersall argues that the species is wrongly classified as Homo floresiensis as it is far too archaic to assign to the genus Homo.[60]

Size

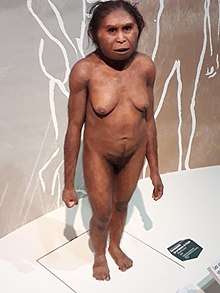

LB1's height is estimated to have been 1.06 m (3 ft 6 in). The height of a second skeleton, LB8, has been estimated at 1.09 m (3 ft 7 in) based on tibial length.[4] These estimates are outside the range of normal modern human height and considerably shorter than the average adult height of even the smallest modern humans, such as the Mbenga and Mbuti at 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in),[61] Twa, Semang at 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) for adult women of the Malay Peninsula,[62] or the Andamanese at also 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) for adult women.[63] LB1's body mass is estimated to have been 25 kg (55 lb). LB1 and LB8 are also somewhat smaller than the australopithecines from three million years ago, not previously thought to have expanded beyond Africa. Thus, LB1 and LB8 may be the shortest and smallest members of the extended human family discovered thus far.

Their short stature was likely due to insular dwarfism, where size decreases as a response to fewer resources in an island ecosystem.[3][64] In 2006, Indonesian palaeoanthropologist Teuku Jacob and colleagues said that LB1 has a similar stature to the Rampasasa pygmies who inhabit the island, and that size can vary substantially in pygmy populations.[44] Of course, the Rampasasa pygmies are completely unrelated to H. floresiensis.[65]

Aside from smaller body size, the specimens seem to otherwise resemble H. erectus, a species known to have been living in Southeast Asia at times coincident with earlier finds purported to be of H. floresiensis.[4]

Brain

In addition to a small body size, H. floresiensis had a remarkably small brain size. LB1's brain is estimated to have had a volume of 380 cm3 (23 cu in), placing it at the range of chimpanzees or the extinct australopithecines.[3][40] LB1's brain size is half that of its presumed immediate ancestor, H. erectus (980 cm3 (60 cu in)).[40] The brain-to-body mass ratio of LB1 lies between that of H. erectus and the great apes.[45] Such a reduction is likely due to insular dwarfism, and a 2009 study found that the reduction in brain size of extinct pygmy hippopotamuses in Madagascar compared with their living relatives is proportionally greater than the reduction in body size, and similar to the reduction in brain size of H. floresiensis compared with H. erectus.[66]

Smaller size does not appear to have affected mental faculties, as Brodmann area 10 on the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with cognition, is about the same size as that of modern humans.[40] H. floresiensis is also associated with evidence for advanced behaviours, such as the use of fire, butchering, and stone tool manufacturing.[4][7]

Limbs

The angle of humeral torsion is much less than in modern humans.[3][4][7] The humeral head of modern humans is twisted between 145 and 165 degrees to the plane of the elbow joint, whereas it is 120 degrees in H. floresiensis. This may have provided an advantage when arm-swinging, and, in tandem with the unusual morphology of the shoulder girdle and short clavicle, would have displaced the shoulders slightly forward into an almost shrugging position. The shrugging position would have compensated for the lower range of motion in the arm, allowing for similar manoeuverability in the elbows as modern humans.[26] The wrist bones are similar to those of apes and Australopithecus, significantly different from those of modern humans, lacking features which evolved at least 800,000 years ago.[25]

The leg bones are thicker than those of modern humans.[3][4][7] The feet were unusually flat and long in relation with the rest of the body.[67] As a result, when walking, they would have had to have bent the knees further back than modern humans do. This caused a high-stepping gait and low walking speed.[68] The toes had an unusual shape and the big toe was very short.[69]

Culture

Because of a deep neighbouring strait, Flores remained isolated during the Wisconsin glaciation (the last glacial period), despite the low sea levels that united Sundaland. Therefore, the ancestors of H. floresiensis could only have reached the isolated island by water transport, perhaps arriving in bamboo rafts around 1 million years ago. Liang Bua Cave shows evidence of the use of fire for cooking, and bones with cut marks. The cave also yielded a great quantity of stone artefacts, mainly lithic flakes. Points, perforators, blades, and microblades were associated with remains of the extinct elephant Stegodon, and were probably hafted into barbs to sink into the elephant. This indicates the inhabitants were targeting juvenile Stegodon. Similar artefacts are found at the Soa Basin 50 km (31 mi) south, associated with Stegodon and Komodo dragon remains, and are attributed to a likely ancestral population of H. erectus.[3][4][7]

Extinction

The youngest bone remains in the cave date to 60,000 years ago, and the youngest stone tools to 50,000 years ago. The previous estimate of 12,000 BCE was due to an undetected unconformity in the cave stratigraphy. Their disappearance is close to the time that modern humans reached the area, suggesting that the initial encounter caused or contributed to their extinction.[70] This would be consistent with the disappearance of H. neanderthalensis from Europe about 40,000 years ago, within 5,000 years after the arrival of modern humans there, and other anthropogenic extinctions.[71] Modern human bones recovered from the cave dating to 46,000 years ago indicate replacement of the former H. floresiensis inhabitants. Other megafauna of the island, such as Stegodon and the giant stork Leptoptilos robustus, also disappeared.[72]

"Hobbit" nickname

H. floresiensis was swiftly nicknamed "the hobbit" by the discoverers, after the fictional race popularized in J. R. R. Tolkien's book The Hobbit, and some of the discoverers suggested naming the species H. hobbitus.[24]

In October 2012, a New Zealand scientist due to give a public lecture on Homo floresiensis was told by the Tolkien Estate that he was not allowed to use the word "hobbit" (the title of J. R. R. Tolkien's book The Hobbit) in promoting the lecture.[73]

In 2012, the American film studio The Asylum, which produces low-budget "mockbuster" films,[74] planned to release a movie entitled Age of the Hobbits depicting a "peace-loving" community of H. floresiensis "enslaved by the Java Men, a race of flesh-eating dragon-riders."[75] The film was intended to piggyback on the success of Peter Jackson's film The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.[76] The film was blocked from release due to a legal dispute about using the word "hobbit."[76] The Asylum argued that the film did not violate the Tolkien copyright because the film was about H. floresiensis, "uniformly referred to as 'Hobbits' in the scientific community."[75] The film was later retitled Clash of the Empires.

See also

- Homo luzonensis – Archaic human from Luzon, Philippines

- Neanderthal – Eurasian species or subspecies of archaic human

- Denisovan – Asian archaic human

References

Citation

- Sutikna, Thomas; Tocheri, Matthew W.; et al. (30 March 2016). "Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia". Nature. 532 (7599): 366–9. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..366S. doi:10.1038/nature17179. PMID 27027286.

- Zimmer, Carl (20 June 2016). "Are Hobbits Real?". New York Times. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Brown, P.; et al. (27 October 2004). "A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature. 431 (7012): 1055–1061. Bibcode:2004Natur.431.1055B. doi:10.1038/nature02999. PMID 15514638.

- Morwood, M. J.; et al. (13 October 2005). "Further evidence for small-bodied hominins from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature. 437 (7061): 1012–1017. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1012M. doi:10.1038/nature04022. PMID 16229067.

- Zimmer, Carl (2 August 2018). "Bodies Keep Shrinking on This Island, and Scientists Aren't Sure Why - The Indonesian island of Flores has given rise to smaller hominins, humans and even elephants". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Argue, Debbie; Groves, Colin P. (21 April 2017). "The affinities of Homo floresiensis based on phylogenetic analyses of cranial, dental, and postcranial characters". Journal of Human Evolution. 107: 107–133. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.02.006. PMID 28438318.

- Morwood, M. J.; et al. (27 October 2004). "Archaeology and age of a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia". Nature. 431 (7012): 1087–1091. Bibcode:2004Natur.431.1087M. doi:10.1038/nature02956. PMID 15510146.

- Sutikna, Thomas; Tocheri, Matthew W.; Morwood, Michael J.; Saptomo, E. Wahyu; Jatmiko; Awe, Rokus Due; Wasisto, Sri; Westaway, Kira E.; Aubert, Maxime; Li, Bo; Zhao, Jian-xin; Storey, Michael; Alloway, Brent V.; Morley, Mike W.; Meijer, Hanneke J. M.; van den Bergh, Gerrit D.; Grün, Rainer; Dosseto, Anthony; Brumm, Adam; Jungers, William L.; Roberts, Richard G. (30 March 2016). "Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia". Nature. 532 (7599): 366–369. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..366S. doi:10.1038/nature17179. PMID 27027286.

- Ritter, Malcolm (30 March 2016). "Study: Indonesia "hobbit" fossils older than first thought". Associated Press. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Amos, Jonathan (30 March 2016). "Age of 'Hobbit' species revised". BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Jungers, W.; Baab, K. (December 2009). "The geometry of hobbits: Homo floresiensis and human evolution". Significance. 6 (4): 159–164. doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2009.00389.x.(subscription required)

- Dalton, Rex (28 October 2004). "Little lady of Flores forces rethink of human evolution". Nature. 431 (7012): 1029. Bibcode:2004Natur.431.1029D. doi:10.1038/4311029a. PMID 15510116.

- Morwood and van Oosterzee 2007

- Marwick, Ben; Clarkson, Chris; O'Connor, Sue; Collins, Sophie (December 2016). "Early modern human lithic technology from Jerimalai, East Timor". Journal of Human Evolution. 101: 45–64. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.004. PMID 27886810.

- Morwood & van Oosterzee (2007) ch. 9

- Connor, Steve (30 November 2004). "Hobbit woman' remains spark row among academics". New Zealand Herald.

- "Fight over access to 'hobbit' bones – being-human". New Scientist. 11 December 2004.

- "Professor fuels row over Hobbit man fossils". Times Online. London, UK. 3 December 2004.

- "Hobbits triumph tempered by tragedy". Sydney Morning Herald. 5 March 2005.

- Powledge, Tabitha M. (28 February 2005). "Flores hominid bones returned". The Scientist. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- "Hobbit cave digs set to restart". BBC News. 25 January 2007.

- Morwood & van Oosterzee (2007) ch. 9, pp. 230-231

- McKie, Robin (21 February 2010). "How a hobbit is rewriting the history of the human race". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- Aiello, Leslie C. (2010). "Five years of Homo floresiensis". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (2): 167–179. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21255. PMID 20229502.

- Tocheri, M.W.; Orr, CM; Larson, SG; Sutikna, T; Jatmiko; Saptomo, EW; Due, RA; Djubiantono, T; et al. (21 September 2007). "The Primitive Wrist of Homo floresiensis and Its Implications for Hominin Evolution" (PDF). Science. 317 (5845): 1743–5. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1743T. doi:10.1126/science.1147143. PMID 17885135.

- Larson et al. 2007 (preprint online Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine)

- Argue, Debbie; et al. (July 2009). "Homo floresiensis: A cladistic analysis". Journal of Human Evolution. Online Only as of Aug 4, 09. (5): 623–639. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.05.002. PMID 19628252.

- Jungers, W. L.; et al. (2009). "The foot of Homo floresiensis". Nature. 459 (7243): 81–84. Bibcode:2009Natur.459...81J. doi:10.1038/nature07989. PMID 19424155.

- Dembo, M.; Matzke, N. J.; Mooers, A. Ø.; Collard, M. (2015). "Bayesian analysis of a morphological supermatrix sheds light on controversial fossil hominin relationships". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1812): 20150943. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0943. PMC 4528516. PMID 26202999.

- Kaifu, Yousuke; Kono, Reiko T.; Sutikna, Thomas; Saptomo, Emanuel Wahyu; Jatmiko, .; Due Awe, Rokus (18 November 2015). Bae, Christopher (ed.). "Unique Dental Morphology of Homo floresiensis and Its Evolutionary Implications". PLOS One. 10 (11): e0141614. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1041614K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141614. PMC 4651360. PMID 26624612.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Dalton, Rex (2010). "Hobbit origins pushed back". Nature. 464 (7287): 335. doi:10.1038/464335a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20237533.

- Brumm, Adam; Jensen, Gitte M.; van den Bergh, Gert D.; Morwood, Michael J.; Kurniawan, Iwan; Aziz, Fachroel; Storey, Michael (2010). "Hominins on Flores, Indonesia, by one million years ago". Nature. 464 (7289): 748–752. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..748B. doi:10.1038/nature08844. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20237472.

- Callaway, E. (8 June 2016). "'Hobbit' relatives found after ten-year hunt". Nature. 534 (7606): 164–165. Bibcode:2016Natur.534Q.164C. doi:10.1038/534164a. PMID 27279191.

- Brumm, A.; van den Bergh, G. D.; Storey, M.; Kurniawan, I.; Alloway, B. V.; Setiawan, R.; Setiyabudi, E.; Grün, R.; Moore, M. W.; Yurnaldi, D.; Puspaningrum, M. R.; Wibowo, U. P.; Insani, H.; Sutisna, I.; Westgate, J. A.; Pearce, N. J. G.; Duval, M.; Meijer, H. J. M.; Aziz, F.; Sutikna, T.; van der Kaars, S.; Flude, S.; Morwood, M. J. (8 June 2016). "Age and context of the oldest known hominin fossils from Flores" (PDF). Nature. 534 (7606): 249–253. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..249B. doi:10.1038/nature17663. PMID 27279222.

- van den Bergh, G. D.; Kaifu, Y.; Kurniawan, I.; Kono, R. T.; Brumm, A.; Setiyabudi, E.; Aziz, F.; Morwood, M. J. (8 June 2016). "Homo floresiensis-like fossils from the early Middle Pleistocene of Flores". Nature. 534 (7606): 245–248. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..245V. doi:10.1038/nature17999. PMID 27279221.

- Zhu Zhaoyu (朱照宇); Dennell, Robin; Huang Weiwen (黄慰文); Wu Yi (吴翼); Qiu Shifan (邱世藩); Yang Shixia (杨石霞); Rao Zhiguo (饶志国); Hou Yamei (侯亚梅); Xie Jiubing (谢久兵); Han Jiangwei (韩江伟); Ouyang Tingping (欧阳婷萍) (2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. 559 (7715): 608–612. Bibcode:2018Natur.559..608Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 29995848.

- Parins-Fukuchi, C.; Greiner, E.; MacLatchy, L. M.; Fisher, D. C. (2019). "Phylogeny, ancestors and anagenesis in the hominin fossil record" (PDF). Paleobiology. 45 (2): 378–393. doi:10.1017/pab.2019.12.

- Cheryl Jones (5 January 2011). "Researchers to drill for hobbit history : Nature News". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.702. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- Falk, D.; et al. (2009). "LB1's virtual endocast, microcephaly and hominin brain evolution". Journal of Human Evolution. 57 (5): 597–607. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.008. PMID 19254807.

- Falk, D.; et al. (8 April 2005). "The Brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis". Science. 308 (5719): 242–5. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..242F. doi:10.1126/science.1109727. PMID 15749690.

- Weber, J.; Czarnetzki, A.; Pusch, C.M. (14 October 2005). "Comment on "The Brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis"". Science. 310 (5746): 236. doi:10.1126/science.1114789. PMID 16224005.

- von Bredow, Rafaela (1 September 2006). "Indonesia's "Hobbit": A Huge Fight over a Little Man". Der Spiegel.

- "'Hobbit' Bones Said to Be of Deformed Human". Los Angeles Times. 20 May 2006.

- Jacob, T.; Indriati, E.; Soejono, R. P.; Hsu, K.; Frayer, D. W.; Eckhardt, R. B.; Kuperavage, A. J.; Thorne, A.; Henneberg, M. (5 September 2006). "Pygmoid Australomelanesian Homo sapiens skeletal remains from Liang Bua, Flores: Population affinities and pathological abnormalities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (36): 13421–13426. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10313421J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605563103. PMC 1552106. PMID 16938848.

- Falk, D.; et al. (19 May 2006). "Response to Comment on 'The Brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis'". Science. 312 (5776): 999c. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.....F. doi:10.1126/science.1124972.

- Argue, D.; Donlon, D.; Groves, C.; Wright, R. (October 2006). "Homo floresiensis: Microcephalic, pygmoid, Australopithecus, or Homo?". Journal of Human Evolution. 51 (4): 360–374. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.013. PMID 16919706.

- Falk, D.; Hildebolt, C.; Smith, K.; Morwood, M.J.; Sutikna, T.; Others (2 February 2007). "Brain shape in human microcephalics and Homo floresiensis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (7): 2513–8. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.2513F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609185104. PMC 1892980. PMID 17277082.

- Lyras, G.A., Dermitzakis, D.M., Van Der Geer, A.A.E., Van der Geer, S.B., De Vos, J. (1 August 2008). "The origin of Homo floresiensis and its relation to evolutionary processes under isolation". Anthropological Science. 117: 33–43. doi:10.1537/ase.080411.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Vannucci, Robert C.; Barron, Todd F.; Holloway, Ralph L. (2013). "Frontal Brain Expansion During Development Using MRI and Endocasts: Relation to Microcephaly and Homo floresiensis". The Anatomical Record. 296 (4): 630–637. doi:10.1002/ar.22663. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 23408553.

- Balzeau, Antoine; Charlier, Philippe (2016). "What do cranial bones of LB1 tell us about Homo floresiensis?". Journal of Human Evolution. 93: 12–24. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.12.008. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 27086053.

- Hershkovitz, Israel; Kornreich, Liora; Laron, Zvi (2007). "Comparative skeletal features between Homo floresiensis and patients with primary growth hormone insensitivity (Laron syndrome)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 134 (2): 198–208. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20655. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 17596857.

- Obendorf, P.J.; Oxnard, C.E.; Kefford, C.E. (7 June 2008). "Are the small human-like fossils found on Flores human endemic cretins?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 275 (1640): 1287–1296. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1488. PMC 2602669. PMID 18319214.

- Groves, C.; Fitzgerald, C. (2010). "Healthy hobbits or victims of Sauron". HOMO: Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 61 (3): 211. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.01.019.

- "Flores hobbits didn't suffer from cretinism". New Scientist. 206 (2766): 17. 2010. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(10)61537-0. ISSN 0262-4079.

- Oxnard, C.; Obendorf, P.J.; Kefford, B.B. (2010). "Post-cranial skeletons of hypothyroid cretins show a similar anatomical mosaic as Homo floresiensis". PLOS ONE. 5 (9): e13018. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513018O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013018. PMC 2946357. PMID 20885948.

- Brown, Peter (2012). "LB1 and LB6 Homo floresiensis are not modern human (Homo sapiens) cretins". Journal of Human Evolution. 62 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.10.011. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 22277102.

- Henneberg, Maciej; Eckhardt, Robert B.; Chavanaves, Sakdapong; Hsü, Kenneth J. (5 August 2014). "Evolved developmental homeostasis disturbed in LB1 from Flores, Indonesia, denotes Down syndrome and not diagnostic traits of the invalid species Homo floresiensis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (31): 11967–11972. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11111967H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1407382111. PMC 4143021. PMID 25092311.

- Westaway, Michel Carrington; Durband, Arthur C. C; Groves, Colin P.; Collard, Mark (17 February 2015). "Mandibular evidence supports Homo floresiensis as a distinct species". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (7): E604–E605. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E.604W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418997112. PMC 4343145. PMID 25659745.

- Baab, Karen (8 June 2016). "A Critical Evaluation of the Down Syndrome Diagnosis for LB1, Type Specimen of Homo floresiensis". PLOS ONE. 11 (6): e0155731. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1155731B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155731. PMC 4898715. PMID 27275928.

- Tattersall, 2015, p. 194

- "Pygmy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- Fix, Alan G. (June 1995). "Malayan Paleosociology: Implications for Patterns of Genetic Variation among the Orang Asli". American Anthropologist. New Series. 97 (2): 313–323. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.2.02a00090. JSTOR 681964.

- "Weber ch. 5". Andaman.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- Van Den Bergh, G. D.; Rokhus Due Awe; Morwood, M. J.; Sutikna, T.; Jatmiko; Wahyu Saptomo, E. (May 2008). "The youngest Stegodon remains in Southeast Asia from the Late Pleistocene archaeological site Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia". Quaternary International. 182 (1): 16–48. Bibcode:2008QuInt.182...16V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.02.001.

- Tucci, S.; et al. (3 August 2018). "Evolutionary history and adaptation of a human pygmy population of Flores Island, Indonesia". Science. 361 (6401): 511–516. Bibcode:2018Sci...361..511T. doi:10.1126/science.aar8486. PMC 6709593. PMID 30072539.

- Weston, E. M.; Lister, A. M. (7 May 2009). "Insular dwarfism in hippos and a model for brain size reduction in Homo floresiensis". Nature. 459 (7243): 85–8. Bibcode:2009Natur.459...85W. doi:10.1038/nature07922. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 2679980. PMID 19424156.

- Jungers, William L.; Larson, S.G.; Harcourt-Smith, W.; Morwood, M.J.; Sutikna, T.; Due Awe, Rokhus; Djubiantono, T. (4 December 2008). "Descriptions of the lower limb skeleton of Homo floresiensis". Journal of Human Evolution. 57 (5): 538–54. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.08.014. PMID 19062072.

- Blaszczyk, Maria B.; Vaughan, Christopher L. (2007). "Re-interpreting the evidence for bipedality in Homo floresiensis". South African Journal of Science. 103 (103): 103.

- Callaway, Ewen (16 April 2008). "Flores 'hobbit' walked more like a clown than Frodo". New Scientist. 3. pp. 983–984.

- Callaway, E. (30 March 2016). "Did humans drive 'hobbit' species to extinction?". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19651.

- Callaway, Ewen (20 August 2014). "Neanderthals: Bone technique redrafts prehistory". Nature. 512 (7514): 242. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..242C. doi:10.1038/512242a. PMID 25143094.

- Callaway, E. (21 September 2016). "Human remains found in hobbit cave". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.20656.

- Lee, Julian (24 October 2012). "Hobbit makers ban uni from using 'hobbit'". 3 News NZ. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- Somma, Brandon (4 January 2013). "Masters of the Mockbuster:What The Asylum Is All About". The Artifice.

- "The Hobbit producers sue 'mockbuster' film company". BBC. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Fritz, Ben (10 December 2012). "'Hobbit' knockoff release blocked by judge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

Sources

- Falk, Dean (2011). The Fossil Chronicles: How Two Controversial Discoveries Changed Our View of Human Evolution. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26670-4.

- Larson, S.G., Jungers, W.L., Morwood, M.J.; et al. (December 2007). "Homo floresiensis and the evolution of the hominin shoulder". Journal of Human Evolution. 53 (6): 718–31. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.06.003. PMID 17692894.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Martin, R. D.; MacLarnon, A. M.; Phillips, J. L.; Dussubieux, L.; Williams, P. R.; Dobyns, W. B. (19 May 2006). "Comment on "The Brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis"". Science. 312 (5776): 999. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.....M. doi:10.1126/science.1121144. PMID 16709768.

- Morwood, Mike; van Oosterzee, Penny (2007). A New Human: The Startling Discovery and Strange Story of the "Hobbits" of Flores, Indonesia. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-0-06-089908-0.

- Stringer, Chris (2011). The Origin of Our Species. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-84614-140-9.

- Tattersall, Ian (2015). The Strange Case of the Rickety Cossack and other Cautionary Tales from Human Evolution. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-27889-0.

- Weber, George. "Lonely islands: The Andamanese (Ch. 5)". Andaman Association. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- Knepper, Gert M. (2019): Floresmens - Het leven van Theo Verhoeven, missionaris en archeoloog. ISBN 978-9-46-3892476 (Bookscout, Soest, The Netherlands) (= a biography of the discoverer of the Liang Bua, in Dutch)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo floresiensis. |

| Wikinews has related news: Bones of "small-bodied humans" found in cave |

| Wikispecies has information related to Homo floresiensis |

- Hawks, John. Blog of a professor of anthropology who closely follows this topic.

- "Another diagnosis for a hobbit" (online). 3 July 2007.

- "The Liang Bua report" (online). 10 August 2007.

- "The forelimb and hindlimb remains from Liang Bua cave" (online). 18 December 2008.

- "Hominin remains from Mata Menge, Flores" (online). 8 June 2016.

- Scientific American Interview with Professor Brown 27 October 2004

- National Geographic News article on H. floresiensis

- Homo floresiensis - The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Obendorf, Peter; Oxnard, Charles E.; Kefford, Ben J. (5 March 2008). "Were Homo floresiensis just a population of myxoedematous endemic cretin Homo sapiens?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. -1 (–1): –1. Blog commentary on the Obendorf paper.

- Washington University in St. Louis Virtual Endocasts of the "Hobbit" – Electronic Radiology Laboratory

- Nova's Alien from Earth documentary website, complete program available through Watch Online feature

- Homo Floresiensis Skeletal Morphology

- Hobbits in the Haystack: Homo floresiensis and Human Evolutions – Turkhana Basin Institute presentment at the Seventh Stony Brook Human Evolution Symposium

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).