Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, 4th Earl of Leicester and Lancaster, Earl of Derby KG (c. 1310 – 23 March 1361), of Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, was a member of the English royal family and a prominent English diplomat, politician, and soldier. He was the wealthiest and most powerful peer of the realm. The son and heir of Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, and Maud Chaworth, he became one of King Edward III's most trusted captains in the early phases of the Hundred Years' War and distinguished himself with victory in the Battle of Auberoche. He was a founding member and the second Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1348, and in 1351 was created Duke of Lancaster. An intelligent and reflective man, Grosmont taught himself to write and was the author of the book Livre de seyntz medicines, a highly personal devotional treatise. He is remembered as one of the founders and early patrons of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, which was established by two guilds of the town in 1352.

| Henry of Grosmont | |

|---|---|

%2C_f.8_-_BL_Stowe_MS_594_(cropped).jpg) Duc de Lancaster, from the Bruges Garter Book (1430) by William Bruges. The arms on his tabard appear to be erroneous, being the arms first adopted by King Edward III and not his paternal arms of Plantagenet with a label of France for difference, being the arms of their common ancestor King Henry III. | |

| Duke of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster and Leicester | |

| Predecessor | Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster |

| Successor | John of Gaunt |

| Born | c. 1310 Grosmont Castle, Grosmont, Monmouthshire |

| Died | 23 March 1361 (aged 50–51) Leicester Castle, Leicester, Leicestershire |

| Burial | 14 April 1361 Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke |

| Spouse | Isabel of Beaumont |

| Issue |

|

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster |

| Mother | Maud Chaworth |

|

Military career

| |

| Allegiance | |

| Wars |

|

| Awards | Knight of the Garter |

Origins

Henry of Grosmont[note 1] was the only son of Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster (c. 1281–1345); who in turn was the younger brother and heir of Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster (c. 1278–1322). They were sons of Edmund Crouchback, 1st Earl of Lancaster (1245–1296); the second son of King Henry III (ruled 1216–1272) and younger brother of King Edward I of England (ruled 1272–1307). Henry of Grosmont was thus a first cousin once removed of King Edward II and a second cousin of King Edward III (ruled 1327–1377). His mother was Maud de Chaworth (1282–1322).[1] On his mother's side Henry of Grosmont was also the great-grandson of Louis VIII of France.[2] Little is known of Grosmont's childhood and youth; the year and place of his birth are not known with certainty. He is believed to have been born in about 1310 at Grosmont Castle in Grosmont, Monmouthshire, Wales.[3] According to his own memoirs he was better at martial arts than at academic subjects, and did not learn to read until later in life.[4]

Henry of Grosmont was the eventual heir of his wealthy uncle Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, who through his marriage to Alice de Lacy, daughter and heiress of Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln, had become the wealthiest peer in England. Constant quarrels between Thomas and his first cousin, King Edward II of England, led to his execution in 1322. Having no progeny, Thomas's possessions and titles went to his younger brother Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, Grosmont's father. Henry of Lancaster assented to the deposition of Edward II in 1327, but fell out of favour with the regency of his widow Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer. When Edward III, the son of Edward II, took personal control of the government in 1330, relations with the Crown improved, but by this time Henry of Lancaster was struggling with blindness and poor health.[5] In 1330 Grosmont was knighted, and represented his father in Parliament and is known to have travelled a great deal between his father's estates, presumably supervising their management. In 1331 he participated in a royal tournament at Cheapside in the City of London.[3][6]

Adult career

Scotland

In 1328 Edward III's regents had agreed to the Treaty of Northampton with Robert Bruce, King of Scotland (r. 1306–1329), but this was widely resented in England and commonly known as turpis pax, "the cowards' peace". Some Scots nobles refused to swear fealty to Bruce, and were disinherited. They left Scotland to join forces with Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland (r. 1292–1296),[7] whom Edward I had deposed in 1296.[8] One of these was Grosmont's father-in-law, Henry de Beaumont, Earl of Buchan and veteran campaigner of the First War of Scottish Independence. Robert Bruce died in 1329; his heir was 5-year-old David II (r. 1329–1371). In 1330 Edward III, who had recently assumed his full powers, made a formal request to the Scottish Crown to restore Beaumont's lands which was refused. In 1331 the disinherited Scottish nobles gathered in Yorkshire, and led by Balliol and Beaumont plotted an invasion of Scotland. Edward III was aware of the scheme but turned a blind eye. Balliol's forces sailed for Scotland on 31 July 1332. Five days after landing in Fife, Balliol's force of some 2,000 men met the Scottish army of 12,000–15,000 men and crushed them at the Battle of Dupplin Moor. Balliol was crowned king of Scotland at Scone on 24 September 1332.[8] Balliol's support within Scotland was limited and within six months it had collapsed. He was ambushed by supporters of David II at the Battle of Annan a few months after his coronation and fled to England half-dressed and riding bareback. He appealed to Edward III for assistance.[9][10]

On 10 March Balliol, the disinherited Scottish lords and some English magnates crossed the border and laid siege to the Scottish town of Berwick-upon-Tweed.[11] Six weeks later a large English army under Edward III joined them, bringing the total number of besiegers to nearly 10,000.[12] Grosmont was present at the siege, but it is not known if he marched with his father-in-law and Balliol, or with the main English effort.[13] The Scots felt compelled to attempt to relieve the siege and an army of 20,000 men attacked the English at the Battle of Halidon Hill, 2 miles (3.2 km) from Berwick. Under intense bow-fire the Scottish army broke, the camp followers made off with the horses and the fugitives were pursued by the mounted English knights. The Scottish casualties numbered in thousands, including their commander and five earls dead on the field.[14] Scots who surrendered were killed on Edward's orders and some drowned as they fled into the sea.[15] English casualties were reported as fourteen; some chronicles give a lower figure of seven.[16][17] About a hundred Scots who had been taken prisoner were beheaded the next morning, 20 July.[18] It is presumed that Grosmont took part in the battle, but it is possible that he was part of the detachment posted to ensure that the garrison of Berwick did not sally.[13] Berwick surrendered the day after the battle and Grosmont witnessed and sealed the articles of surrender and, a little later, the town's new charter.[13]

Encouraged by the French King, most Scots refused to accept Balliol as their monarch. In December 1334 Grosmont accompanied Edward III to Roxburgh in Scotland. The English force of 4,000 accompanied little and withdrew in February. Grosmont was a member of Edward III's negotiation team when a brief truce was agreed shortly after at Nottingham. In July Grosmont accompanied Edward III on another invasion of Scotland, with an army of 13,000 – for the time an extremely large force. Scotland was quelled as far as Perth and Grosmont took a senior role in raiding deeper into the country.[19] In 1336 Grosmont was given command of 500 men-at-arms and 1,000 longbowmen and marched to Perth. He was given full plenipotentiary powers by the King. After Edward III reached Perth with the main English army, Grosmont was despatched on a long-range raid to Aberdeen, 80 miles (100 km) away. He returned after two weeks, having razed Aberdeen and devastated the country on the way.[20] Edward went south for six weeks, leaving Grosmont in charge of English-occupied Scotland. Believing that he would soon be at war with France, Edward withdrew most of his forces from Scotland in mid-1336 and sent Grosmont to London to plan the defence of the English Channel ports from the mouth of the Thames westward.[21]

From 1333 Grosmont's father had begun transferring estates into Grosmont's name, giving him an independent income. In 1337 he was one of six men Edward III promoted to the higher levels of the peerage; one of his father's lesser titles, earl of Derby, was bestowed upon him. He was also granted a royal annuity of 1,000 marks[note 2] (£935,900 as of 2020[note 3]) for so long as his father lived, and a number of lucrative estates and perquisites were settled on him.[24][25] During early 1337 Grosmont was again serving in Scotland. By the time he returned to London, war with France had commenced.[note 4]

North-east France

In 1338 Grosmont travelled with Edward III to Flanders, and to a meeting with Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, at Coblenz. This was a diplomatic mission amidst much pageantry; Edward III concluded agreements with a number of rulers, including Louis IV, whereby they would provide troops in exchange for payment and was appointed Imperial vicar. Throughout the year, French naval forces ravaged the English south coast.[28] Edward III planned to invade France with his army of allies in 1339, but was finding it impossible to raise the money to pay them; he and his ambassadors had committed him to far greater expense than the Exchequer could fund. Grosmont led part of Edward III's army when it finally invaded France in September 1339.[29][30] Cambrai was besieged, the area around it devastated, and an unsuccessful attempt made to storm the town. The allied army pressed further into France, but the French refused battle. Then, in mid-October, the French issued a formal challenge to battle. Edward accepted and occupied a strong defensive position at La Capelle which the French declined to attack. Having run out of provisions, money and weather suitable for campaigning, the allied army withdrew and dispersed. Grosmont arrived in Brussels with the army at the end of October, where the campaign was celebrated with a Tournament.[31]

From 29 March to 3 April 1340 Grosmont attended Parliament, where a substantial subsidy was voted to the crown.[32] Meanwhile, encouraged by Edward III, the Flemings, vassals of Philip IV, had revolted during the winter. They joined forces with Edward III's continental allies and launched an April offensive, which failed. A French offensive against these forces commenced on 18 May, meeting with mixed fortunes; Edward's outnumbered allies were desperate for the English army to reinforce them.[33]

Grosmont was present at the great English victory in the naval Battle of Sluys in 1340.[30] Later the same year, he was required to commit himself as hostage in the Low Countries for the king's considerable debts. He remained hostage until the next year and had to pay a large ransom for his own release.[34] On his return he was made the king's lieutenant in the north and stayed at Roxburgh until 1342. The next years he spent in diplomatic negotiations in the Low Countries, Castile and Avignon.[3]

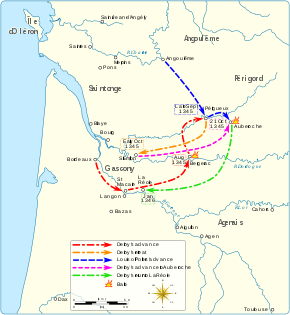

1345

Edward III determined early in 1345 to attack France on three fronts. The Earl of Northampton would lead a small force to Brittany, a slightly larger force would proceed to Gascony under the command of Grosmont, and the main force would accompany Edward to either northern France or Flanders.[35][36][37] Grosmont was appointed the King's Lieutenant in Gascony on 13 March 1345[38] and received a contract to raise a force of 2,000 men in England, and further troops in Gascony itself.[39] The highly detailed contract of indenture had a term of six months from the opening of the campaign in Gascony, with an option for Edward to extend it for a further six months on the same terms.[40] Derby was given a high degree of autonomy, for example his strategic instructions were: "si guerre soit, et a faire le bien q'il poet" (... if there is war, do the best you can ...).[41]

On 9 August 1345 Grosmont arrived in Bordeaux with 500 men-at-arms, 1,500 English and Welsh archers, 500 of them mounted on ponies to increase their mobility,[42] and ancillary and support troops.[43] Rather than continue the cautious war of sieges he was determined to strike directly at the French before they could concentrate their forces.[44] He decided to strike at the French at Bergerac, which had good river supply links to Bordeaux, and would provide the Anglo-Gascon army with a base from which to carry the war to the French[45] and sever communications between French forces north and south of the Dordogne. After eight years of defensive warfare by the Anglo-Gascons, there was no expectation among the French that they might make any offensive moves.[42] Grosmont moved rapidly and took the French army at Bergerac by surprise on 26 August, decisively beating them in a running battle.[46] French casualties were heavy, many being killed or captured.[47] Derby's share of the ransoms and the loot was estimated at £34,000 (£33,000,000 in 2020 terms[note 5]), approximately four times the annual income from his lands.[note 6][49]

Grosmont left a large garrison in the town and moved north with 6,000–8,000 men[50] to Périgueux, the provincial capital of Périgord,[51] which Grosmont blockaded, taking several strongholds on the main routes into the city. John, Duke of Normandy, the son and heir of Philip VI, gathered an army reportedly numbering over 20,000 and manoeuvred in the area. In early October a very large detachment relieved the city and drove off Grosmont's force and started besieging the English-held strongpoints.[52] A French force of 7,000 besieged the castle of Auberoche, 9 miles (14 km) east of Périgueux.[53] A messenger got through to Grosmont, who was already returning to the area with a scratch force of 1,200 English and Gascon soldiers: 400 men-at-arms and 800 mounted archers.[54]

After a night march Grosmont attacked the French camp on 21 October while they were at dinner, taking them by surprise. There was a protracted hand-to-hand struggle, which ended when the commander of the small English garrison in the castle sortied and fell upon the rear of the French. They broke and fled. Derby's mounted men-at-arms pursued them relentlessly. French casualties are uncertain, but were heavy. They are described by modern historians as "appalling",[55] "extremely high",[51] "staggering",[56] and "heavy".[53] Many French nobles were taken prisoner; lower ranking men were, as was customary,[57] put to the sword. The ransoms alone made a fortune for many of the soldiers in Grosmont's army, as well as Grosmont himself, who was said to have made at least £50,000 (£49,000,000 in 2020 terms) from the day's captives.[58]

1346

John, Duke of Normandy, the son and heir of Philip VI, was placed in charge of all French forces in southwest France, as he had been the previous autumn. In March 1346 a French army under Duke John, numbering between 15,000 and 20,000,[59] enormously superior to any force the Anglo-Gascons could field,[60] marched on the town of Aiguillon, which commanded the junction of the Rivers Garonne and Lot, meaning it was not possible to sustain an offensive further into Gascony unless the town was taken, and besieged it on 1 April.[59] On 2 April an arrière-ban, a formal call to arms for all able-bodied males, was announced for southern France.[59][61] Grosmont, now known as Lancaster after the death of his father,[note 7] sent an urgent appeal for help to Edward.[62] Edward was not only morally obliged to succour his vassal, but also contractually required to; his indenture with Lancaster stated that if Lancaster were attacked by overwhelming numbers, then Edward "shall rescue him in one way or another".[63]

The garrison, some 900 men, sortied repeatedly to interrupt the French operations, while Lancaster concentrated the main Anglo-Gascon force at La Réole, some 30 miles (48 km) away, as a threat. Duke John was never able to fully blockade the town, and found that his own supply lines were seriously harassed. On one occasion Grosmont used his main force to escort a large supply train into the town.

In July the main English army landed in northern France and moved towards Paris. Philip VI repeatedly ordered his son, Duke John, to break off the siege and bring his army north. Duke John, considering it a matter of honour, refused. By August, the French supply system had broken down, there was a dysentery epidemic in their camp, desertion was rife and Philip VI's orders were becoming imperious. On 20 August the French abandoned the siege and their camp and marched away. Six days later the main French army was decisively beaten in the Battle of Crécy with very heavy losses. Two weeks after this defeat, Duke John's army joined the French survivors. Meanwhile, the English laid siege to the port of Calais.

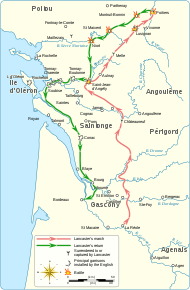

Philip vacillated: on the day the siege of Calais began he disbanded most of his army, to save money and convinced that Edward had finished his chevauchée and would proceed to Flanders and ship his army home. On or shortly after 7 September, Duke John made contact with Philip, having shortly before disbanded his own army. On 9 September Philip announced that the army would reassemble at Compiègne on 1 October, an impossibly short interval, and then march to the relief of Calais.[64] Among other consequences, this equivocation allowed Grosmont in the south west to launch offensives into Quercy and the Bazadais; and himself lead a chevauchée 160 miles (260 km) north through Saintonge, Aunis and Poitou, capturing numerous towns, castles and smaller fortified places and storming the rich city of Poitiers. These offensives completely disrupted the French defences and shifted the focus of the fighting from the heart of Gascony to 60 miles (97 km) or more beyond its borders.[65][66][67] Few French troops had arrived at Compiègne by 1 October and as Philip and his court waited for the numbers to swell, news of Lancaster's conquests came in. Believing that Lancaster was heading for Paris, the French changed the assembly point for any men not already committed to Compiègne to Orléans, and reinforced them with some of those already mustered, to block this. After Lancaster turned south to head back to Gascony, those Frenchmen already at or heading towards Orléans were redirected to Compiègne; French planning collapsed into chaos.[68]

Duke of Lancaster

In 1345, while Grosmont was in France, his father died. The younger Henry was now Earl of Lancaster – the wealthiest and most powerful peer of the realm. After participating in the Siege of Calais in 1347, the king honoured Lancaster by including him as a founding member and the second Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1348.[69][70] In the same year Alice de Lacy died and her life holdings (which she had retained after Thomas of Lancaster was executed), including the Honour of Bolingbroke and Bolingbroke Castle, passed to Grosmont. A few years later, in 1351, Edward bestowed an even greater honour on Lancaster when he created him Duke of Lancaster. The title of duke was of relatively new origin in England; only one other English ducal title existed previously.[note 8]

In addition to this, the dukedom was given palatinate powers over the county of Lancashire, which entitled him to administer it virtually independently of the crown.[71] This grant was quite exceptional in English history; only two other counties palatine existed: Durham, which was an ancient episcopal palatinate, and Chester, which was held by the crown.

It is a sign of Edward's high regard for Lancaster that he bestowed such extensive privileges on him. The two men were second cousins through their great-grandfather King Henry III and practically coeval (Edward was born in 1312), so it is natural to assume that a strong sense of camaraderie existed between them. Another factor that might have influenced the king's decision was the fact that Henry had no male heir, so the grant was made for the Earl's lifetime only, and not intended to be hereditary.[3]

Further prestige

Lancaster spent the 1350s intermittently campaigning and negotiating peace treaties with the French. In 1350 he was present at the naval victory at Battle of Les Espagnols sur Mer (Winchelsea), where he allegedly saved the lives of the Black Prince and John of Gaunt,[72] sons of Edward III. The years 1351–1352 he spent on crusade in Prussia. It was here that a quarrel with Otto, Duke of Brunswick, almost led to a duel between the two men, narrowly averted by the intervention of King John II of France.[73] In the later half of the decade campaigning in France resumed. After a chevauchée in Normandy in 1356 and the Siege of Rennes (1356–57), Lancaster participated in the last great offensive of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War: the Rheims campaign of 1359–1360. Then he was appointed principal negotiator for the Treaty of Brétigny, where the English achieved very favourable terms.[3]

By the time he died in 1361 Henry had participated in 15 military missions, leading 6 of them; been the King's lieutenant 7 times; led 6 significant embassies; and taken part in 12 truce conferences.[74]

Death and burial

After returning to England in November 1360, he fell ill early the next year, and died at Leicester Castle on 23 March 1361. It is possible that the cause of death was the plague, which that year was making a second visitation to England.[75][note 9] He was buried in the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke, Leicester, which he had built within the religious and charitable institution founded by his father next to Leicester Castle, and where he had reburied his father some years previously.[76]

Personal life

Grosmont's mother died when he was about 12, and at about age 18 he married Isabel of Beaumont; daughter of Henry de Beaumont, Earl of Buchan and veteran campaigner of the First War of Scottish Independence. Grosmont and Elizebeth were to have two daughters. The eldest was Maud of Lancaster (4 April 1340 – 10 April 1362), who married William I, Duke of Bavaria in 1352.[77] The younger was Blanche of Lancaster (25 March 1345/1347 – 12 September 1368), who married her third cousin John of Gaunt (1340–1399); the third of five surviving sons of King Edward III. Gaunt inherited Lancaster's possessions, and he was granted the ducal title the following year, but it was not until 1377, when the dying King Edward III was largely incapacitated, that he was able to recover the palatinate rights for the County of Lancaster. When Gaunt's son by Blanche, Henry of Bolingbroke, usurped the crown in 1399 and became King Henry IV, the vast Lancaster inheritance, including the Honour of Bolingbroke and the Lordship of Bowland, was merged with the Crown as the Duchy of Lancaster.[78]

Character

More is known about Lancaster's character than that of most of his contemporaries through his memoirs, the Livre de seyntz medicines ("Book of the Holy Doctors"), a highly personal treatise on matters of religion and piety, also containing details of historical interest. It reveals that Lancaster, at the age of 44 when he wrote the book in 1354, suffered from gout.[3] The book is primarily a devotional work, organised around seven wounds which Henry claimed to have received, representing the seven deadly sins. Lancaster confesses to his sins, explains various real and mythical medical remedies in terms of their theological symbolism, and exhorts the reader to greater morality.[79]

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

References:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- In his early years Henry was known, as was customary at the time, after his birthplace, Grosmont.[1]

- A medieval English mark was an accounting unit equivalent to two-thirds of a pound sterling.[22]

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. To give a very rough idea of earning power, an English foot-soldier could expect to earn £1 in wages in approximately 3 months for, usually seasonal, military service.[23]

- Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, English monarchs had held titles and lands within France, the possession of which made them vassals of the kings of France. By 1337 only Gascony in southwestern France and Ponthieu in northern France were left.[26] Following a series of disagreements between Philip VI of France (r. 1328–1350) and Edward III of England (r. 1327–1377), including over who was the rightful king of Scotland, on 24 May 1337 Philip's Great Council agreed Gascony should be taken back into Philip's hands, on the grounds that Edward was in breach of his obligations as a vassal. This marked the start of the Hundred Years' War, which was to last 116 years.[27]

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- For comparison, Edward III's annual income was often less than £50,000.[48]

- During the 1345 campaign he was known as the Earl of Derby, but his father died in September 1345 and he became the Earl of Lancaster. Sumption 1990, p. 476

- This was the Duke of Cornwall, a title created for Edward, the Black Prince in 1337. Before that, early Norman kings of England had been Duke of Normandy, but this had been a French title.

- Mortimer argues against plague being the cause of death, as

- Henry made his will ten days before his death, a space of time inconsistent with the usual swift progress of the plague;

- his illness and death in early 1361 is inconsistent with the spread of plague in England being reported from about May 1361

Citations

- Fowler 1969, p. 23.

- Dunbabin 2014, p. 244.

- Ormrod 2005.

- Fowler 1969, p. 26.

- Waugh 2004.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 27–28.

- Weir 2006, p. 314.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 19.

- Wyntourn 1907, p. 395.

- Maxwell 1913, pp. 274–275.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 22.

- Maxwell 1913, pp. 278–279.

- Fowler 1969, p. 30.

- Sumption 1990, p. 130.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 41.

- Strickland & Hardy 2011, p. 188.

- Nicholson 1961, p. 42.

- King 2002, p. 281.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 31–32.

- Fowler 1969, p. 32.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 32–33.

- Harding 2002, p. xiv.

- Gribit 2016, p. 37.

- McFarlane 1973, pp. 158–159.

- Fowler 1969, p. 28.

- Harris 1994, p. 8.

- Sumption 1990, p. 184.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 242–244, 260–265.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 276–279.

- Fowler 1969, p. 34.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 279–281, 281, 283, 285, 287–289, 290.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 305–306.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 309–318, 322.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 35–37.

- Guizot 1870s.

- Sumption 1990, p. 453.

- Prestwich 2007, p. 314.

- Gribit 2016, p. 63.

- Sumption 1990, p. 455.

- Gribit 2016, pp. 37–38.

- Gribit 2016, pp. 113, 251.

- Rogers 2004, p. 95.

- Fowler 1961, p. 178.

- Rogers 2004, p. 97.

- Vale 1999, p. 77.

- Rogers 2004, pp. 90–94, 98–104.

- Sumption 1990, p. 465.

- Rogers 2004, p. 90, n. 7.

- Rogers 2004, p. 105.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 465–467.

- DeVries 1996, p. 189.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 467–468.

- Wagner 2006.

- Burne 1999, p. 107.

- Sumption 1990, p. 469.

- Burne 1999, p. 112.

- King 2002, pp. 269–270.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 469–470.

- Wagner 2006, p. 3.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 485–486.

- Sumption 1990, p. 485.

- Harari 1999, p. 384.

- Sumption 1990, p. 493.

- Sumption 1990, p. 539.

- Harari 1999, pp. 385–386.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 67–71.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 541–550.

- Sumption 1990, p. 554.

- Beltz 1841, p. cxlix.

- McKisack 1976, p. 252.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 173–174.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 93–95.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 106–109.

- Fowler 1969, p. 20.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 217–218.

- Billson 1920.

- Burke's 1973, p. 196.

- Brown & Summerson 2006.

- Fowler 1969, pp. 193–196.

Sources

- Arnauld, E.J., ed. (1940). Le livre de seyntz medicines: The Unpublished Devotional Treatise of Henry of Lancaster (in French). Oxford: Blackwell. OCLC 1001064358.

- Beltz, George Frederick (1841). Memorials of the Order of the Garter. London: William Pickering. OCLC 865663564. Retrieved 27 October 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Billson, Charles James (1920). Mediaeval Leicester. Leicester: Edgar Backus. OCLC 558085282.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, A. L.; Summerson, Henry (May 2006). "Henry IV (1366–1413)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12951. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Burke's (1973). Burke's Guide to the Royal Family. Burke's Genealogical Series. London: Burke's Peerage. ISBN 0220662223.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burne, Alfred (1999) [1955]. The Crecy War. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-84022-210-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crowcroft, Robert; Cannon, John (2015). "Gascony". The Oxford Companion to British History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curry, Anne (2002). The Hundred Years' War 1337–1453 (PDF). Oxford: Osprey Publishing (published 13 November 2002). ISBN 978-1-84176-269-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guizot, François (1870s). Chapter XX. The Hundred Years' War – Philip VI and John II. A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times. Translated by Robert Black. Boston: D. Estes and C.E. Lauriat. OCLC 916066180. Retrieved 6 December 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DeVries, Kelly (1996). Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century: Discipline, Tactics, and Technology. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-567-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunbabin, Jean (2014). Charles I of Anjou: Power, Kingship and State-Making in Thirteenth-Century. London; NewYork: Routledge. ISBN 978-0582253704.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Kenneth (1961). Henry of Grosmont, First Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361 (PDF) (Thesis). Leeds: University of Leeds.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Kenneth Alan (1969). The King's Lieutenant: Henry of Grosmont, First Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361. New York: Barnes & Noble. OCLC 164491035.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gribit, Nicholas A. (2016). Henry of Lancaster's Expedition to Aquitaine, 1345–1346: Military Service and Professionalism in the Hundred Years War. Warfare in History. 42. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-78327-117-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harari, Yuval Noah (1999). "Inter-frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III's 1346 Campaign". War in History. 6 (4 (November 1999)): 379–395. JSTOR 26013966.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harding, V. (2002). The Dead and the Living in Paris and London, 1500–1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521811262.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Robin (1994). Valois Guyenne. Royal Historical Society Studies in History. 71. London: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-86193-226-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, Andy (2002). "According to the Custom Used in French and Scottish Wars: Prisoners and Casualties on the Scottish Marches in the Fourteenth Century". Journal of Medieval History. 28 (3): 263–290. doi:10.1016/S0048-721X(02)00057-X. ISSN 0304-4181.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucas, Henry S. (1929). The Low Countries and the Hundred Years' War: 1326–1347. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. OCLC 960872598.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFarlane, K. B. (1973). The Nobility of Later Medieval England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-19-822362-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKisack, M. (1976) [1959]. The Fourteenth Century: 1307–1399. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821712-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maxwell, Herbert (1913). The Chronicle of Lanercost, 1272–1346. Glasgow: J. Maclehose. OCLC 27639133.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicholson, Ranald (1961). "The Siege of Berwick, 1333". The Scottish Historical Review. XXXX (129): 19–42. JSTOR 25526630. OCLC 664601468.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oman, Charles (1998) [1924]. A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages: 1278–1485 A.D. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-332-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ormrod, W. M. (2005). "Henry of Lancaster, First Duke of Lancaster (c.1310–1361)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12960.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Prestwich, M. (2007). J.M. Roberts (ed.). Plantagenet England 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922687-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rodger, N. A. M. (2004). The Safeguard of the Sea. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-029724-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogers, Clifford J. (2004). Bachrach, Bernard S.; DeVries, Kelly; Rogers, Clifford J. (eds.). The Bergerac Campaign (1345) and the Generalship of Henry of Lancaster. Journal of Medieval Military History. 2. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-040-5. ISSN 0961-7582.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogers, Clifford J. (2010). "Aiguillon, Siege of". In Rogers, Clifford J. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0195334036.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strickland, Matthew; Hardy, Robert (2011). The Great Warbow: From Hastings to the Mary Rose. Somerset: J. H. Haynes & Co. ISBN 978-0-85733-090-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sumption, Jonathan (1990). The Hundred Years War I: Trial by Battle. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-20095-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vale, Malcolm (1999). "The War in Aquitaine". In Curry, Anne; Hughes, Michael (eds.). Arms, Armies and Fortifications in the Hundred Years War. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 69–82. ISBN 978-0-85115-755-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wagner, John A. (2006). "Auberoche, Battle of (1345)". Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Greenwood. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waugh, Scott L. (September 2004). "Henry of Lancaster, third Earl of Lancaster and third Earl of Leicester (c.1280–1345)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12959.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Weir, Alison (2006). Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-34545-320-4. Retrieved 25 March 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wyntourn, Andrew (1907). Amours, François Joseph (ed.). The Original Chronicle of Scotland. II. Edinburgh: Blackwood. OCLC 61938371.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

Maddicott, J. R. (1970). Thomas of Lancaster, 1307–1322: A study in the reign of Edward II. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821837-0.

External links

- Britannia.com

- Online version of Livre de seyntz medicines (in the original Anglo-Norman)

- Inquisition Post Mortem #118, dated 1361.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Earl of Lancaster |

Lord High Steward 1345–1361 |

Succeeded by Duke of Lancaster |

| Peerage of England | ||

| New creation | Duke of Lancaster First creation 1351–1361 |

Extinct |

| Earl of Lincoln Fifth Creation 1349–1361 | ||

| Earl of Derby 1337–1361 |

Succeeded by John of Gaunt | |

| Preceded by Henry of Lancaster |

Earl of Leicester Earl of Lancaster 1345–1361 | |