George M. Dallas

George Mifflin Dallas (July 10, 1792 – December 31, 1864) was an American politician and diplomat who served as mayor of Philadelphia from 1828 to 1829 and as the 11th vice president of the United States from 1845 to 1849.

George M. Dallas | |

|---|---|

| |

| 11th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1845 – March 4, 1849 | |

| President | James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | John Tyler |

| Succeeded by | Millard Fillmore |

| United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office April 4, 1856 – May 16, 1861 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce James Buchanan Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Charles Francis Adams Sr. |

| United States Minister to Russia | |

| In office August 6, 1837 – July 29, 1839 | |

| President | Martin Van Buren |

| Preceded by | John Randolph Clay |

| Succeeded by | Churchill C. Cambreleng |

| 17th Attorney General of Pennsylvania | |

| In office October 14, 1833 – December 1, 1835 | |

| Governor | George Wolf |

| Preceded by | Ellis Lewis |

| Succeeded by | James Todd |

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania | |

| In office December 13, 1831 – March 3, 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Isaac D. Barnard |

| Succeeded by | Samuel McKean |

| 80th Mayor of Philadelphia | |

| In office 1828–1829 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Wood Richards |

| United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania | |

| In office 1829–1831 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Charles Jared Ingersoll |

| Succeeded by | Henry D. Gilpin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Mifflin Dallas July 10, 1792 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | December 31, 1864 (aged 72) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. Peter's Episcopal Church |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Sophia Chew |

| Children | 8 |

| Relatives | Alexander Dallas (Father) |

| Education | Princeton University (BA) |

| Signature | |

The son of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas, George Dallas attended elite preparatory schools before embarking on a legal career. He served as the private secretary to Albert Gallatin and worked for the Treasury Department and the Second Bank of the United States. He emerged as a leader of the "Family party" faction of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party, and Dallas developed a rivalry with James Buchanan, the leader of the "Amalgamator" faction. Between 1828 and 1835, he served as the mayor of Philadelphia, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and the Pennsylvania Attorney General. He also represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1831 to 1833 but declined to seek re-election. President Martin Van Buren appointed Dallas to the post of Minister to Russia, and Dallas held that position from 1837 to 1839.

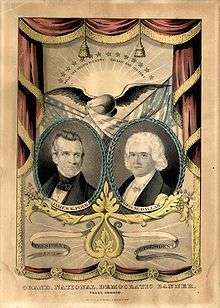

Dallas supported Van Buren's bid for another term in the 1844 presidential election, but James K. Polk won the party's presidential nomination. The 1844 Democratic National Convention nominated Dallas as Polk's running mate, and Polk and Dallas defeated the Whig ticket in the general election. A supporter of expansion and popular sovereignty, Dallas called for the annexation of all of Mexico during the Mexican–American War. He sought to position himself for contention in the 1848 presidential election, but his vote to lower the tariff destroyed his base of support in his home state. Dallas served as the ambassador to Britain from 1856 to 1861 before retiring from public office.

Family and early life

George Mifflin Dallas was born on July 10, 1792, to Alexander James Dallas and Arabella Maria Smith Dallas (born Devon, England) in Philadelphia.[1] His father, born in Kingston, Jamaica, and educated in Edinburgh, was the Secretary of the Treasury under United States President James Madison, and was also briefly the Secretary of War.[1] George Dallas was given his middle name after Thomas Mifflin, another politician who was good friends with his father.[2]

Dallas was the second of six children,[1] another of whom, Alexander, would become the commander of Pensacola Navy Yard. During Dallas's childhood, the family lived in a mansion on Fourth Street, with a second home in the countryside, situated on the Schuylkill River. He was educated privately at Quaker-run preparatory schools, before studying at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), from which he graduated with highest honors in 1810.[2] While at College, he participated in several activities, including the American Whig–Cliosophic Society.[3] Afterwards, he studied law in his father's office, and he was admitted to the bar in 1813.[1]

Early legal, diplomatic and financial service

As a new graduate, Dallas had little enthusiasm for legal practice; he wanted to fight in the War of 1812, a plan that he dropped due to his father's objection.[1] Just after this, Dallas accepted an offer to be the private secretary of Albert Gallatin, and he went to Russia with Gallatin who was sent there to try to secure its aid in peace negotiations between Great Britain and the United States.[1] Dallas enjoyed the opportunities offered to him by being in Russia, but after six months there he was ordered to go to London to determine whether the War of 1812 could be resolved diplomatically.[1] In August 1814, he arrived in Washington, D.C., and delivered a preliminary draft of Britain's peace terms.[1] There, he was appointed by James Madison to become the remitter of the treasury, which is considered a "convenient arrangement" because Dallas's father was serving at the time as that department's secretary.[1] Since the job did not entail a large workload, Dallas found time to develop his grasp of politics, his major vocational interest.[1] He later became the counsel to the Second Bank of the United States.[1] In 1817, Dallas's father died, ending Dallas's plan for a family law practice, and he stopped working for the Second Bank of the United States and became the deputy attorney general of Philadelphia, a position he held until 1820.[1]

Political career

After the War of 1812 ended, Pennsylvania's political climate was chaotic, with two factions in that state's Democratic party vying for control.[1] One, the Philadelphia-based "Family party", was led by Dallas, and it espoused the beliefs that the Constitution of the United States was supreme, that an energetic national government should exist that would implement protective tariffs, a powerful central banking system, and undertake internal improvements to the country in order to facilitate national commerce.[1] The other faction was called the "Amalgamators", headed by the future President James Buchanan.[1]

Voters elected Dallas mayor of Philadelphia as the candidate of the Family party, after the party had gained control of the city councils.[1] However, he quickly grew bored of that post, and became the United States attorney for the eastern district of Pennsylvania in 1829, a position his father had held from 1801 to 1814, and continued in that role until 1831.[1] In December of that year, he won a five-man, eleven-ballot contest in the state legislature, that enabled him to become the Senator from Pennsylvania in order to complete the unexpired term[1] of the previous senator who had resigned.[4]

Dallas served less than fifteen months—from December 13, 1831, to March 3, 1833. He was chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs. Dallas declined to seek re-election, in part due to a fight over the Second Bank of the United States, and in part because his wife did not want to leave Philadelphia for Washington.[5]

Dallas resumed the practice of law, was attorney general of Pennsylvania from 1833 to 1835, was initiated to the Scottish Rite Freemasonry at the Franklin Lodge #134, Pennsylvania,[6][7] and served as the Grand Master of Freemasons in Pennsylvania in 1835.[8] He was appointed by President Martin Van Buren as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Russia from 1837 to 1839, when he was recalled at his own request. Dallas was offered the role of Attorney General, but declined, and resumed his legal practice.[5] In the lead-up to the 1844 presidential election, Dallas worked to help Van Buren win the Democratic nomination over Dallas's fellow Pennsylvanian, James Buchanan.[5]

At the May 1844 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, James K. Polk and Silas Wright were nominated as the Democratic ticket. However, Wright declined the nomination, and the delegates chose Dallas as his replacement. Dallas, who was not at the convention, was awakened at his home by convention delegates who had traveled to Philadelphia to tell him the news. Dallas somewhat reluctantly accepted the nomination. The Democratic candidates won the popular vote by a margin of 1.5%, and won the election with an electoral vote of 170 out of 275.[5]

Dallas was influential as the presiding officer of the Senate, where he worked to support Polk's agenda and cast several tie-breaking votes. Dallas called for the annexation of all of the Oregon Territory and all of Mexico during the Mexican–American War, but was satisfied with compromises that saw the United States annex parts of both areas. Though Dallas was unsuccessful in preventing Polk from appointing Buchanan as Secretary of State, he helped convince Polk to appoint Robert J. Walker as Secretary of the Treasury. As Vice President, Dallas sought to maneuver himself into contention for the presidency in the 1848 election, as Polk had promised to serve only one term. However, Dallas's reluctant vote to lower a tariff destroyed much of his base in Pennsylvania, and Dallas's advocacy of popular sovereignty on the question of slavery strengthened opposition against him. Dallas served as Vice President from March 4, 1845 to March 4, 1849.[5]

In 1856, Franklin Pierce appointed Dallas minister to Great Britain, and continued in that post from February 4, 1856, until the appointment by President Lincoln of Charles F. Adams, who relieved him on May 16, 1861. At the very beginning of his diplomatic service in England he was called to act upon the Central American question, and the request made by the United States to the British government that Sir John Crampton, the British minister to the United States, should be recalled. Mr. Dallas managed these delicate questions in a conciliatory spirit, but without any sacrifice of national dignity, and both were settled amicably. At the close of his diplomatic career Dallas returned to private life and took no further part in public affairs except to express condemnation of secession.[5]

Rivalry with James Buchanan

Dallas was a political rival of fellow Pennsylvanian James Buchanan, the future 15th President of the United States. The rivalry was rooted in the power struggle in the Pennsylvania Democratic Party between the "Family party" and the "Amalgamators".

Led by Dallas, the Philadelphia-based "Family party" shared his belief in the supremacy of the Constitution and in an active national government that would impose protective tariffs, operate a strong central banking system, and promote so-called internal improvements to facilitate national commerce. The opposing "Amalgamators" were led by the equally patrician James Buchanan of Harrisburg; their strength lay among the farmers of western Pennsylvania.

The Family party gained control of the Philadelphia city councils, and in 1828 elected Dallas as mayor. Boredom with that post quickly led Dallas—in his father's path—to the position of district attorney for the eastern district of Pennsylvania, where he stayed from 1829 to 1831. In December 1831 he won a five-man, eleven-ballot contest in the state legislature for election to an unexpired term in the U.S. Senate. In the Senate for only fourteen months, he chaired the Naval Affairs Committee and supported President Andrew Jackson's views on protective tariffs and the use of force to enforce the federal tariff in South Carolina.[5]

The tension with Buchanan intensified in 1833–1834, when Buchanan returned from his diplomatic post in Russia and was elected to Pennsylvania's other seat in the U.S. Senate.

Although off the national stage, Dallas remained active in state Democratic politics. Dallas turned down opportunities to return to the Senate and to become U.S. Attorney General. Instead, he accepted an appointment as state Attorney General, holding that post until 1835, when control of the state party machinery shifted from the declining Family party to Buchanan's Amalgamators."[5]

In 1837, it was Dallas's turn for political exile, as newly elected President Martin Van Buren named him U.S. minister to Russia. Although Dallas enjoyed the social responsibilities of that post, he soon grew frustrated at its lack of substantive duties and returned to the United States in 1839. He found that during his absence in St. Petersburg, Buchanan had achieved a commanding position in Pennsylvania politics.[5]

In December 1839, Van Buren offered to appoint Dallas as U.S. Attorney General after Buchanan had rejected the post. Dallas again declined the offer and spent the following years building his Philadelphia law practice. His relations with Buchanan remained troubled throughout this period.

He remained at odds with Buchanan for many years. In 1845, when Buchanan was appointed Secretary of State by President Polk, Dallas vehemently objected.[9]

Tariffs

Dallas determined that he would use his vice-presidential position to advance two of the administration's major objectives: tariff reduction and territorial expansion. As a Pennsylvanian, Dallas had traditionally supported the protectionist tariff policy that his state's coal and iron interests demanded. But as vice president, elected on a platform dedicated to tariff reduction, he agreed to do anything necessary to realize that goal. Dallas equated the vice president's constitutional power to break tied votes in the Senate with the president's constitutional power to veto acts of Congress. At the end of his vice-presidential term, Dallas claimed that he cast thirty tie-breaking votes during his four years in office (although only nineteen of these have been identified in Senate records). Taking obvious personal satisfaction in this record, Dallas singled out this achievement and the fairness with which he believed he accomplished it in his farewell address to the Senate. Not interested in political suicide, however, Dallas sought to avoid having to exercise his singular constitutional prerogative on the tariff issue, actively lobbying senators during the debate over Treasury Secretary Walker's tariff bill in the summer of 1846. He complained to his wife (whom he sometimes addressed as "Mrs. Vice") that the Senate speeches on the subject were "as vapid as inexhaustible ... All sorts of ridiculous efforts are making, by letters, newspaper-paragraphs, and personal visits, to affect the Vice's casting vote, by persuasion or threat."

Despite Dallas's efforts to avoid taking a stand, the Senate completed its voting on the Walker Tariff with a 27-to-27 tie. (A twenty-eighth vote in favor was held in reserve by a Senator who opposed the measure but agreed to follow the instructions of his state legislature to support it.) When he cast the tie-breaking vote in favor of the tariff on July 28, 1846, Dallas rationalized that he had studied the distribution of Senate support and concluded that backing for the measure came from all regions of the country. Additionally, the measure had overwhelmingly passed the House of Representatives, a body closer to public sentiment. He apprehensively explained to the citizens of Pennsylvania that "an officer, elected by the suffrages of all twenty-eight states, and bound by his oath and every constitutional obligation, faithfully and fairly to represent, in the execution of his high trust, all the citizens of the Union" could not "narrow his great sphere and act with reference only to [Pennsylvania's] interests." While his action, based on a mixture of party loyalty and political opportunism, earned Dallas the respect of the President and certain party leaders—and possible votes in 1848 from the southern and western states that supported low tariffs—it effectively demolished his home state political base, ending any serious prospects for future elective office. (He even advised his wife in a message hand-delivered by the Senate Sergeant at Arms, "If there be the slightest indication of a disposition to riot in the city of Philadelphia, owing to the passage of the Tariff Bill, pack up and bring the whole brood to Washington.")

While Dallas's tariff vote destroyed him in Pennsylvania, his aggressive views on Oregon and the Mexican War crippled his campaign efforts elsewhere in the nation. In his last hope of building the necessary national support to gain the White House, the Vice President shifted his attention to the aggressive, expansionist foreign policy program embodied in the concept of "Manifest Destiny." He actively supported efforts to gain control of Texas, the Southwest, Cuba, and disputed portions of the Oregon territory.[5]

Death

Dallas returned to Philadelphia, and lived in Philadelphia until his death from a heart attack on December 31, 1864, at the age of 72.[10] He is interred in St. Peter's Churchyard.

Legacy

Dallas County, Iowa[11] and one of its cities, Dallas Center, Iowa,[12] were named after the Vice President. In addition, Dallas County, Arkansas, Dallas County, Missouri,[13] and Dallas County, Texas[14] were named in his honor.

Other U.S. cities and towns named in Dallas's honor include Dallas, Georgia (the county seat of Paulding County, Georgia),[15] Dallas, North Carolina (the former county seat of Gaston County, North Carolina),[16] Dallas, Oregon (the county seat of Polk County, Oregon)[17] and Dallastown, Pennsylvania[18] It is debated whether the city of Dallas, Texas is named after the Vice President—see History of Dallas, Texas (1839–1855) for more information.

References

- "George Mifflin Dallas, 11th Vice President (1845–1849)".

- Belohlavek. "George Mifflin Dallas", p. 109.

- "Daily Princetonian – Special Class of 1979 Issue 25 July 1975 — Princeton Periodicals". Theprince.princeton.edu. 1975-07-25. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- "Barnard, Isaac Dutton, (1791–1834)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "George Mifflin Dallas, 11th Vice President (1845–1849)". U.S. Senate: Art & History Home. Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- "Celebrating more than 100 years of the Freemasonry: famous Freemasons in the history". Mathawan Lodge No 192 F.A. & A.M., New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008.

- Berre Heleen (1837). Journal. 47 (Part 2). pp. 576–577. ISBN 978-1847245748. OCLC 145380045. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved Oct 24, 2018.

Report attempting upon the account of George M. Dallas, a witness attending before the committed appointed to inquire into the evils of Freemasonry, at the session of 1835-1836.

- "George Mifflin Dallas – 1835". Pagrandlodge.org. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- Seigenthaler (2004), pp. 107–108.

- Belohlavek, "George Mifflin Dallas", p. 118.

- "Profile for Dallas County, Iowa, IA". ePodunk. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Dallas Center, Iowa". City-Data.com. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Profile for Dallas County, Missouri MO". ePodunk. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Profile for Dallas County, Texas, TX". ePodunk. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Profile for Dallas, Georgia, GA". ePodunk. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Profile for Dallas, North Carolina, NC". ePodunk. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Profile for Dallas, Oregon, OR". ePodunk. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Profile for Dallastown, Pennsylvania, PA". ePodunk. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

Bibliography

- Ambacher, Bruce (1975). "George M. Dallas and the Bank War". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 42 (2): 116–135. JSTOR 27772269.

- Ambacher, Bruce (1973). "George M. Dallas, Cuba, and the Election of 1856". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 97 (3): 318–332. JSTOR 20090763.

- Ambacher, Bruce Irwin (1971). George M. Dallas: Leader of the "Family" Party. Temple University.

- Belohlavek, John M. (1972). "Dallas, the Democracy, and the Bank War of 1832". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 96 (3): 377–390. JSTOR 20090654.

- Belohlavek, John M. (1974). "The Democracy in a Dilemma: George M. Dallas, Pennsylvania, and the Election of 1844". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 41 (4): 390–411. JSTOR 27772234.

- Belohlavek, John (2010). "George Mifflin Dallas". In L.Edward Purcell (ed.). Vice Presidents: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. pp. 108–118. ISBN 9781438130712.

- "George Mifflin Dallas." Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936.

- Hatfield, Mark O. George Mifflin Dallas. Vice-Presidents of the United States, 1789–1983. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1979.

- "George Mifflin Dallas, 11th Vice President (1845–1849)". United States Senate. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about George M. Dallas. |

- "George Mifflin Dallas". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- George Mifflin Dallas at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- A Series of Letters Written from London by George M. Dallas

- Manuscript Diaries of George M. Dallas at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries

- George M. Dallas at Find a Grave

- "Barnard, Isaac Dutton, (1791–1834)". United States Congress.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Joseph Watson |

Mayor of Philadelphia 1828–1829 |

Succeeded by Benjamin Wood Richards |

| Preceded by John Tyler |

Vice President of the United States 1845–1849 |

Succeeded by Millard Fillmore |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by Charles Jared Ingersoll |

U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania 1829–1831 |

Succeeded by Henry D. Gilpin |

| Preceded by Ellis Lewis |

Attorney General of Pennsylvania 1833–1835 |

Succeeded by James Todd |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by Isaac D. Barnard |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Pennsylvania 1831–1833 Served alongside: William Wilkins |

Succeeded by Samuel McKean |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by John Clay |

United States Minister to Russia 1837–1839 |

Succeeded by Churchill C. Cambreleng |

| Preceded by James Buchanan |

United States Minister to Britain 1856–1861 |

Succeeded by Charles Adams |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Richard Mentor Johnson Littleton Tazewell James K. Polk1 |

Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States 1844 |

Succeeded by William Orlando Butler |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. The Democratic vice presidential nominee was split this year among three candidates. | ||