Enalapril

Enalapril, sold under the brand name Vasotec among others, is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, diabetic kidney disease, and heart failure.[2] For heart failure, it is generally used with a diuretic, such as furosemide.[3] It is given by mouth or by injection into a vein.[2] Onset of effects are typically within an hour when taken by mouth and last for up to a day.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vasotec, Renitec, Enacard, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a686022 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | ACE inhibitor |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% (by mouth) |

| Metabolism | liver (to enalaprilat) |

| Elimination half-life | 11 hours (enalaprilat) |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

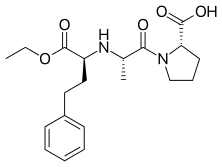

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.119.661 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H28N2O5 |

| Molar mass | 376.447 g/mol g·mol−1 |

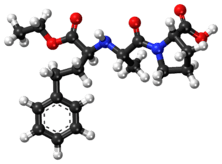

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 143 to 144.5 °C (289.4 to 292.1 °F) |

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include headache, tiredness, feeling lightheaded with standing, and cough.[2] Serious side effects include angioedema and low blood pressure.[2] Use during pregnancy is believed to result in harm to the baby.[2] It is in the angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor family of medications.[2]

Enalapril was patented in 1978, and came into medical use in 1984.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[5] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.08 to US$0.80 per month.[6] In the United States, it costs about US$25 to US$50 per month.[7] In 2017, it was the 122nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than six million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical uses

Enalapril is used to treat hypertension, symptomatic heart failure, and asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction.[10] It has been proven to protect the function of the kidneys in hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes, and may be used in the absence of hypertension for its kidney protective effects.[11] It is widely used in chronic kidney failure.[12] Furthermore, enalapril is an emerging treatment for psychogenic polydipsia. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that when used for this purpose, enalapril led to decreased water consumption (determined by urine output and osmality) in 60% of patients.[13]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Enalapril is pregnancy category D. Some evidence suggests it will cause injury and death to a developing fetus. Patients are advised not to become pregnant while taking enalapril and to notify their doctors immediately if they become pregnant. In pregnancy, enalapril may result in damage to the fetus's kidneys and resulting oligohydramnios (not enough amniotic fluid). Enalapril is secreted in breast milk and is not recommended for use while breastfeeding.[14]

Side effects

The most common side effects of enalapril include increased serum creatinine (20%), dizziness (2–8%), low blood pressure (1–7%), syncope (2%), and dry cough (1–2%). The most serious common adverse event is angioedema (swelling) (0.68%) which often affects the face and lips, endangering the patient's airway. Angioedema can occur at any point during treatment with enalapril, but is most common after the first few doses.[14] Angioedema and fatality therefrom are reportedly higher among black people.[14]

Mechanism of action

Normally, angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II by an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Angiotensin II constricts blood vessels, increasing blood pressure. Enalaprilat, the active metabolite of enalapril, inhibits ACE. Inhibition of ACE decreases levels of angiotensin II, leading to less vasoconstriction and decreased blood pressure.[14]

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic data of enalapril:[14]

- Onset of action: about 1 hour

- Peak effect: 4–6 hours

- Duration: 12–24 hours

- Absorption: ~60%

- Metabolism: prodrug, undergoes biotransformation to enalaprilat[15]

History

Squibb developed the first ACE inhibitor, captopril, but it had adverse effects such as a metallic taste (which, as it turned out, was due to the sulfhydryl group). Merck & Co. developed enalapril as a competing prodrug.[16][17]:12–13

Enalaprilat was developed partly to overcome these limitations of captopril. The sulfhydryl moiety was replaced by a carboxylate moiety, but additional modifications were required in its structure-based design to achieve a potency similar to captopril. Enalaprilat, however, had a problem of its own in that it had poor oral availability. This was overcome by the researchers at Merck by the esterification of enalaprilat with ethanol to produce enalapril.[17]:13

Merck introduced enalapril to market in 1981; it became Merck's first billion dollar-selling drug in 1988.[17]:13 The patent expired in 2000, opening the way for generics.[18]

References

- "Enalapril Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Enalaprilat/Enalapril Maleate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 286. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 467. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Enalapril". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 120. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Enalapril Maleate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Last Revised October 1, 2010 MedlinePlus: Enalapril Archived 2015-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- McMurray JJ (January 2010). "Clinical practice. Systolic heart failure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (3): 228–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0909392. PMID 20089973.

Two large trials showed that when patients with NYHA class II, III, or IV heart failure were treated with enalapril, as compared with placebo, in addition to diuretics and digoxin, the rates of admission to the hospital were reduced, and the relative risk reduction for death was 16 to 40%.

- He YM, Feng L, Huo DM, Yang ZH, Liao YH (September 2013). "Enalapril versus losartan for adults with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nephrology. 18 (9): 605–14. doi:10.1111/nep.12134. PMID 23869492.

- Greendyke RM, Bernhardt AJ, Tasbas HE, Lewandowski KS (April 1998). "Polydipsia in chronic psychiatric patients: therapeutic trials of clonidine and enalapril". Neuropsychopharmacology. 18 (4): 272–81. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00159-0. PMID 9509495.

- FDA Label: Enalapril Maleate Tablet Archived 2014-04-16 at the Wayback Machine Last updated April 2011

- Menard J and Patchett A. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Pp 14-76 in Drug Discovery and Design. Volume 56 of Advances in Protein Chemistry. Eds Richards FM, Eisenberg DS, and Kim PS. Series Ed. Scolnick EM. Academic Press, 2001. ISBN 9780080493381. Pg 30 Archived 2017-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Bryan J (April 2009). "From snake venom to ACE inhibitor--The discovery and rise of captopril". Pharmaceutical Journal. 282 (7548): 455.

- Li JJ (April 2013). "Chapter 1: History of Drug Discovery". In Li JJ, Corey EJ (eds.). Drug Discovery: Practices, Processes, and Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118354469.

- Staff, Drug Discovery Online. Patent expiry looms: 18 blockbusters expose $37 billion to generic competition by 2005 Archived 2016-05-12 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed April 23, 2016