Durga

Durga (Sanskrit: दुर्गा, IAST: Durgā), identified as Adi Parashakti, is a principal and popular form of the Hindu Goddess.[4][5][6] She is a goddess of war, the warrior form of Parvati, whose mythology centres around combating evils and demonic forces that threaten peace, prosperity, and Dharma the power of good over evil.[5][7] Durga is also a fierce form of the protective mother goddess, who unleashes her divine wrath against the wicked for the liberation of the oppressed, and entails destruction to empower creation.[8]

| Durga | |

|---|---|

Durga | |

| Affiliation | Adi-Parashakti, Sati, Parvati, Ambika, Kaushiki, Mahakali, Bhagavati, Chandi |

| Weapon | Chakra (discus), Shankha (conch shell), Trishula (Trident), Gada (mace), Bow and Arrow, Khanda (sword) and Shield, Ghanta (bell) |

| Mount | Tiger or Lion[1][2] |

| Festivals | Durga Puja, Durga Ashtami, Navratri, Vijayadashami |

| Personal information | |

| Siblings | Ganga Vishnu |

| Consort | Shiva[3] |

| Children | Kartikeya, Ganesha, Ashok Sundari |

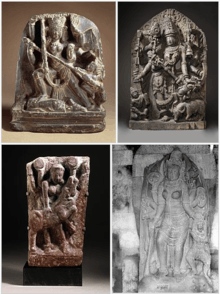

Durga is depicted in the Hindu pantheon as a Goddess riding a lion or tiger, with many arms each carrying a weapon,[2] often defeating Mahishasura (lit. buffalo demon).[9][10][11] The three principal forms of Durga worshiped are Maha Durga, Chandika and Aparajita. Of these, Chandika has two forms called Chandi who is of the combined power and form of Saraswati, Lakshmi and Parvati and of Chamunda who is a form of Kali created by the goddess for killing demons Chanda and Munda. Maha Durga has three forms: Ugrachanda, Bhadrakali and Katyayani.[12][13] Bhadrakali Durga is also worshiped in the form of her nine epithets called Navadurga.

She is a central deity in Shaktism tradition of Hinduism, where she is equated with the concept of ultimate reality called Brahman.[14][7] One of the most important texts of Shaktism is Devi Mahatmya, also known as Durgā Saptashatī or Chandi patha, which celebrates Durga as the goddess, declaring her as the supreme being and the creator of the universe.[15][16][17] Estimated to have been composed between 400 and 600 CE,[18][19][20] this text is considered by Shakta Hindus to be as important a scripture as the Bhagavad Gita.[21][22] She has a significant following all over India, Bangladesh and Nepal, particularly in its eastern states such as West Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand, Assam and Bihar. Durga is revered after spring and autumn harvests, specially during the festival of Navratri.[23][24]

Etymology and nomenclature

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

|

Main traditions

|

|

Concepts

|

|

Practices Worship

Arts

Festivals

|

|

Philosophical schools

|

|

Gurus, saints, philosophers

|

|

Texts Scriptures

Other texts

Text classification

|

|

Other topics

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Shaktism |

|---|

|

|

Scriptures and texts

|

|

Schools |

|

Scholars

|

|

Festivals and temples

|

|

|

The word Durga (दुर्गा) literally means "impassable",[23] [4] "invincible, unassailable".[25] It is related to the word Durg (दुर्ग) which means "fortress, something difficult to defeat or pass". According to Monier Monier-Williams, Durga is derived from the roots dur (difficult) and gam (pass, go through).[26] According to Alain Daniélou, Durga means "beyond defeat".[27]

The word Durga and related terms appear in the Vedic literature, such as in the Rigveda hymns 4.28, 5.34, 8.27, 8.47, 8.93 and 10.127, and in sections 10.1 and 12.4 of the Atharvaveda.[26][28][note 1] A deity named Durgi appears in section 10.1.7 of the Taittiriya Aranyaka.[26] While the Vedic literature uses the word Durga, the description therein lacks the legendary details about her that is found in later Hindu literature.[30]

The word is also found in ancient post-Vedic Sanskrit texts such as in section 2.451 of the Mahabharata and section 4.27.16 of the Ramayana.[26] These usages are in different contexts. For example, Durg is the name of an Asura who had become invincible to gods, and Durga is the goddess who intervenes and slays him. Durga and its derivatives are found in sections 4.1.99 and 6.3.63 of the Ashtadhyayi by Pāṇini, the ancient Sanskrit grammarian, and in the commentary of Nirukta by Yaska.[26] Durga as a demon-slaying goddess was likely well established by the time the classic Hindu text called Devi Mahatmya was composed, which scholars variously estimate to between 400 and 600 CE.[18][19][31] The Devi Mahatmya and other mythologies describe the nature of demonic forces symbolised by Mahishasura as shape-shifting and adapting in nature, form and strategy to create difficulties and achieve their evil ends, while Durga calmly understands and counters the evil in order to achieve her solemn goals.[32][33][note 2]

There are many epithets for Durga in Shaktism and her nine appellations are (Navadurga): Shailaputri, Brahmacharini, Chandraghanta, Kushmanda, Skandamata, Katyayini, Kaalratri, Mahagauri and Siddhidatri. A list of 108 names of the goddess are recited in order to worship her and is popularly known as the "Ashtottarshat Namavali of Goddess Durga".

Other meanings may include: "the one who cannot be accessed easily",[26] "the undefeatable goddess".[27]

One famous shloka states the definition and origin of the term 'Durga': "Durge durgati nashini", meaning Durga is the one who destroys all distress.

History and texts

One of the earliest evidence of reverence for Devi, the feminine nature of God, appears in chapter 10.125 of the Rig Veda, one of the scriptures of Hinduism. This hymn is also called the Devi Suktam hymn (abridged):[35][36]

I am the Queen, the gatherer-up of treasures, most thoughtful, first of those who merit worship.

Thus gods have established me in many places with many homes to enter and abide in.

Through me alone all eat the food that feeds them, – each man who sees, breathes, hears the word outspoken.

They know it not, yet I reside in the essence of the Universe. Hear, one and all, the truth as I declare it.

I, verily, myself announce and utter the word that gods and men alike shall welcome.

I make the man I love exceedingly mighty, make him nourished, a sage, and one who knows Brahman.

I bend the bow for Rudra [Shiva], that his arrow may strike, and slay the hater of devotion.

I rouse and order battle for the people, I created Earth and Heaven and reside as their Inner Controller.

On the world's summit I bring forth sky the Father: my home is in the waters, in the ocean as Mother.

Thence I pervade all existing creatures, as their Inner Supreme Self, and manifest them with my body.

I created all worlds at my will, without any higher being, and permeate and dwell within them.

The eternal and infinite consciousness is I, it is my greatness dwelling in everything.

Devi's epithets synonymous with Durga appear in Upanishadic literature, such as Kali in verse 1.2.4 of the Mundaka Upanishad dated to about the 5th century BCE.[38] This single mention describes Kali as "terrible yet swift as thought", very red and smoky colored manifestation of the divine with a fire-like flickering tongue, before the text begins presenting its thesis that one must seek self-knowledge and the knowledge of the eternal Brahman.[39]

Durga, in her various forms, appears as an independent deity in the Epics period of ancient India, that is the centuries around the start of the common era.[40] Both Yudhisthira and Arjuna characters of the Mahabharata invoke hymns to Durga.[38] She appears in Harivamsa in the form of Vishnu's eulogy, and in Pradyumna prayer.[40] Various Puranas from the early to late 1st millennium CE dedicate chapters of inconsistent mythologies associated with Durga.[38] Of these, the Markandeya Purana and the Devi-Bhagavata Purana are the most significant texts on Durga.[41][42] The Devi Upanishad and other Shakta Upanishads, mostly dated to have been composed in or after the 9th century, present the philosophical and mystical speculations related to Durga as Devi and other epithets, identifying her to be the same as the Brahman and Atman (self, soul).[43][44]

Origins

The historian Ramaprasad Chanda stated in 1916 that Durga evolved over time in the Indian subcontinent. A primitive form of Durga, according to Chanda, was the result of "syncretism of a mountain-goddess worshiped by the dwellers of the Himalaya and the Vindhyas", a deity of the Abhiras conceptualised as a war-goddess. Durga then transformed into Kali as the personification of the all-destroying time, while aspects of her emerged as the primordial energy (Adya Sakti) integrated into the samsara (cycle of rebirths) concept and this idea was built on the foundation of the Vedic religion, mythology and philosophy.[45]

Epigraphical evidence indicates that regardless of her origins, Durga is an ancient goddess. The 6th-century CE inscriptions in early Siddhamatrika script, such as at the Nagarjuni hill cave during the Maukhari era, already mention the legend of her victory over Mahishasura (buffalo-hybrid demon).[46]

European traders and colonial era references

Some early European accounts refer to a deity known as Deumus, Demus or Deumo. Western (Portuguese) sailors first came face to face with the murti of Deumus at Calicut on the Malabar Coast and they concluded it to be the deity of Calicut. Deumus is sometimes interpreted as an aspect of Durga in Hindu mythology and sometimes as deva. It is described that the ruler of Calicut (Zamorin) had a murti of Deumus in his temple inside his royal palace.[47]

Attributes and iconography

Durga has been a warrior goddess, and she is depicted to express her martial skills. Her iconography typically resonates with these attributes, where she rides a lion or a tiger,[1] has between eight and eighteen hands, each holding a weapon to destroy and create.[48][49] She is often shown in the midst of her war with Mahishasura, the buffalo demon, at the time she victoriously kills the demonic force. Her icon shows her in action, yet her face is calm and serene.[50][51] In Hindu arts, this tranquil attribute of Durga's face is traditionally derived from the belief that she is protective and violent not because of her hatred, egotism or getting pleasure in violence, but because she acts out of necessity, for the love of the good, for liberation of those who depend on her, and a mark of the beginning of soul's journey to creative freedom.[51][52][53]

Durga traditionally holds the weapons of various male gods of Hindu mythology, which they give her to fight the evil forces because they feel that she is the shakti (energy, power).[54] These include chakra, conch, bow, arrow, sword, javelin, shield, and a noose.[55] These weapons are considered symbolic by Shakta Hindus, representing self-discipline, selfless service to others, self-examination, prayer, devotion, remembering her mantras, cheerfulness and meditation. Durga herself is viewed as the "Self" within and the divine mother of all creation.[56] She has been revered by warriors, blessing their new weapons.[57] Durga iconography has been flexible in the Hindu traditions, where for example some intellectuals place a pen or other writing implements in her hand since they consider their stylus as their weapon.[57]

Archeological discoveries suggest that these iconographic features of Durga became common throughout India by about the 4th century CE, states David Kinsley – a professor of religious studies specialising on Hindu goddesses.[58] Durga iconography in some temples appears as part of Mahavidyas or Saptamatrkas (seven mothers considered forms of Durga). Her icons in major Hindu temples such as in Varanasi include relief artworks that show scenes from the Devi Mahatmya.[59]

Durga appears in Hindu mythology in numerous forms and names, but ultimately all these are different aspects and manifestations of one goddess. She is imagined to be terrifying and destructive when she has to be, but benevolent and nurturing when she needs to be.[60] While anthropomorphic icons of her, such as those showing her riding a lion and holding weapons, are common, the Hindu traditions use aniconic forms and geometric designs (yantra) to remember and revere what she symbolises.[61]

Worship and festivals

Durga is worshipped in Hindu temples across India and Nepal by Shakta Hindus. Her temples, worship and festivals are particularly popular in eastern and northeastern parts of Indian subcontinent during Durga puja, Dashain and Navaratri.[2][23][62]

Durga puja

As per Markandya Puran, Durga puja can be performed either for 9 days or 4 days (last four in sequence). The four-day-long Durga Puja is a major annual festival in Bengal, Odisha, Assam, Jharkhand and Bihar.[2][23] It is scheduled per the Hindu luni-solar calendar in the month of Ashvin,[63] and typically falls in September or October. Since it is celebrated during Sharad (literally, season of weeds), it is called as Sharadiya Durga Puja or Akal-Bodhan to differentiate it from the one celebrated originally in spring. The festival is celebrated by communities by making special colorful images of Durga out of clay,[64] recitations of Devi Mahatmya text,[63] prayers and revelry for nine days, after which it is taken out in procession with singing and dancing, then immersed in water. The Durga puja is an occasion of major private and public festivities in the eastern and northeastern states of India.[2][65][66]

The day of Durga's victory is celebrated as Vijayadashami (Bijoya in Bengali), Dashain (Nepali) or Dussehra (in Hindi) – these words literally mean "the victory on the Tenth (day)".[67]

This festival is an old tradition of Hinduism, though it is unclear how and in which century the festival began. Surviving manuscripts from the 14th century provide guidelines for Durga puja, while historical records suggest royalty and wealthy families were sponsoring major Durga puja public festivities since at least the 16th century.[65] The 11th or 12th century Jainism text Yasatilaka by Somadeva mentions a festival and annual dates dedicated to a warrior goddess, celebrated by the king and his armed forces, and the description mirrors attributes of a Durga puja.[63]

The prominence of Durga puja increased during the British Raj in Bengal.[68] After the Hindu reformists identified Durga with India, she became an icon for the Indian independence movement.

Dashain

In Nepal, the festival dedicated to Durga is called Dashain (sometimes spelled as Dasain), which literally means "the ten".[62] Dashain is the longest national holiday of Nepal, and is a public holiday in Sikkim and Bhutan. During Dashain, Durga is worshipped in ten forms (Shailaputri, Brahmacharini, Chandraghanta, Kushmanda, Skandamata, Katyayani, Kalaratri, Mahagauri, Mahakali and Durga) with one form for each day in Nepal. The festival includes animal sacrifice in some communities, as well as the purchase of new clothes and gift giving. Traditionally, the festival is celebrated over 15 days, the first nine-day are spent by the faithful by remembering Durga and her ideas, the tenth day marks Durga's victory over Mahisura, and the last five days celebrate the victory of good over evil.[62]

During the first nine days, nine aspects of Durga known as Navadurga are meditated upon, one by one during the nine-day festival by devout Shakti worshippers. Durga Puja also includes the worship of Shiva, who is Durga's consort, in addition to Lakshmi, Saraswati, Ganesha and Kartikeya, who are considered to be Durga's children.[69] Some Shaktas worship Durga's symbolism and presence as Mother Nature. In South India, especially Andhra Pradesh, Dussera Navaratri is also celebrated and the goddess is dressed each day as a different Devi, all considered equivalent but another aspect of Durga.

Other countries

In Bangladesh, the four-day-long Sharadiya Durga Puja is the most important religious festival for the Hindus and celebrated across the country with Vijayadashami being a national holiday. In Sri Lanka, Durga in the form of Vaishnavi, bearing Vishnu's iconographic symbolism is celebrated. This tradition has been continued by Sri Lankan diaspora.[70]

In Buddhism

According to Hajime Nakamura, over its history, some Buddhist traditions adopted Vedic and Hindu ideas and symbols. For example, the fierce Vajrayana Buddhist meditational deity Yamantaka, also known as Vajrabhairava, developed from the pre-Buddhist god of death, Yama.[72] The Tantric traditions of Buddhism included Durga and developed the idea further.[73] In Japanese Buddhism, she appears as Butsu-mo (sometimes called Koti-sri).[74] In Tibet, the goddess Palden Lhamo is similar to the protective and fierce Durga.[75][71]

In Jainism

The Sacciya mata found in major medieval era Jain temples mirrors Durga, and she has been identified by Jainism scholars to be the same or sharing a more ancient common lineage.[76] In the Ellora Caves, the Jain temples feature Durga with her lion mount. However, she is not shown as killing the buffalo demon in the Jain cave, but she is presented as a peaceful deity.[77]

In Sikhism

Durga is exalted as the divine in Dasam Granth, a sacred text of Sikhism that is traditionally attributed to Guru Gobind Singh.[78] According to Eleanor Nesbitt, this view has been challenged by Sikhs who consider Sikhism to be monotheistic, who hold that a feminine form of the Supreme and a reverence for the Goddess is "unmistakably of Hindu character".[78]

Outside Indian subcontinent

Archeological site excavations in Indonesia, particularly on the island of Java, have yielded numerous statues of Durga. These have been dated to be from 6th century onwards.[79] Of the numerous early to mid medieval era Hindu deity stone statues uncovered on Indonesian islands, at least 135 statues are of Durga.[80] In parts of Java, she is known as Loro Jonggrang (literally, "slender maiden").[81]

In Cambodia, during its era of Hindu kings, Durga was popular and numerous sculptures of her have been found. However, most differ from the Indian representation in one detail. The Cambodian Durga iconography shows her standing on top of the cut buffalo demon head.[82]

Durga statues have been discovered at stone temples and archaeological sites in Vietnam, likely related to Champa or Cham dynasty era.[83][84]

Influence

Durga is a major goddess in Hinduism, and the inspiration of Durga Puja – a large annual festival particularly in the eastern and northeastern states of India.[85]

One of the devotees of her form as Kali was Sri Ramakrishna who was the guru of Swami Vivekananda. He is the founder of the Ramakrishna Mission.

Durga as the mother goddess is the inspiration behind the song Vande Mataram, written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, during Indian independence movement, later the official national song of India. Durga is present in Indian Nationalism where Bharat Mata i.e. Mother India is viewed as a form of Durga. This is completely secular and keeping in line with the ancient ideology of Durga as Mother and protector to Indians. She is present in pop culture and blockbuster Bollywood movies like Jai Santoshi Maa. The Indian Army uses phrases like "Durga Mata ki Jai!" and "Kaali Mata ki Jai!". Any woman who takes up a cause to fight for goodness and justice is said to have the spirit of Durga in her.[86][87]

See also

- Surath

- Garh Jungle

- Devi-Bhagavata Purana

- Devi Mahatmya

- Durga Puja

- Loro Jonggrang – Javanese name for Durga

- Lehara Durga Mandir

- Shaktism

- Churrio Jabal

- Jwaladevi Temple

Notes

- It appears in Khila (appendix, supplementary) text to Rigveda 10.127, 4th Adhyaya, per J. Scheftelowitz.[29]

- In the Shakta tradition of Hinduism, many of the stories about obstacles and battles have been considered as metaphors for the divine and demonic within each human being, with liberation being the state of self-understanding whereby a virtuous nature and society emerging victorious over the vicious.[34]

References

- Robert S Ellwood & Gregory D Alles 2007, p. 126.

- Wendy Doniger 1999, p. 306.

- "Early Hinduism (2nd century BCE–4th century CE)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Encyclopedia Britannica 2015.

- David R Kinsley 1989, pp. 3–4.

- Charles Phillips, Michael Kerrigan & David Gould 2011, pp. 93–94.

- Paul Reid-Bowen 2012, pp. 212–213.

- Laura Amazzone 2012, pp. 3–5.

- David R Kinsley 1989, pp. 3–5.

- Laura Amazzone 2011, pp. 71–73.

- Donald J LaRocca 1996, pp. 5–6.

- "Durga". www.kamakotimandali.com. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "kAtyAyanI". www.kamakotimandali.com. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Lynn Foulston & Stuart Abbott 2009, pp. 9–17.

- June McDaniel 2004, pp. 215–216.

- David Kinsley 1988, pp. 101–102.

- Laura Amazzone 2012, p. xi.

- Cheever Mackenzie Brown 1998, p. 77 note 28.

- Thomas B. Coburn 1991, pp. 13.

- Thomas B. Coburn 2002, p. 1.

- Ludo Rocher 1986, p. 193.

- Hillary Rodrigues 2003, pp. 50–54.

- James G Lochtefeld 2002, p. 208.

- Constance Jones & James D Ryan 2006, pp. 139–140, 308–309.

- Laura Amazzone 2012, p. xxii.

- Monier Monier Williams (1899), Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press, page 487

- Alain Daniélou 1991, p. 21.

- Maurice Bloomfield (1906), A Vedic concordance, Series editor: Charles Lanman, Harvard University Press, page 486;

Example Sanskrit original: "अहन्निन्द्रो अदहदग्निरिन्दो पुरा दस्यून्मध्यंदिनादभीके । दुर्गे दुरोणे क्रत्वा न यातां पुरू सहस्रा शर्वा नि बर्हीत् ॥३॥ – Rigveda 4.28.8, Wikisource - J Scheftelowitz (1906). Indische Forschungen. Verlag von M & H Marcus. pp. 112 line 13a.

- David Kinsley 1988, pp. 95–96.

- Thomas B. Coburn 2002, pp. 1–7.

- Alain Daniélou 1991, p. 288.

- June McDaniel 2004, pp. 215–219.

- June McDaniel 2004, pp. 20–21, 217–219.

- June McDaniel 2004, p. 90.

- Cheever Mackenzie Brown 1998, p. 26.

- The Rig Veda/Mandala 10/Hymn 125 Ralph T.H. Griffith (Translator); for Sanskrit original see: ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १०.१२५

- Rachel Fell McDermott 2001, pp. 162–163.

- Mundaka Upanishad, Robert Hume, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 368–377 with verse 1.2.4

- Rachel Fell McDermott 2001, p. 162.

- Ludo Rocher 1986, pp. 168–172, 191–193.

- C Mackenzie Brown 1990, pp. 44–45, 129, 247–248 with notes 57–60.

- Douglas Renfrew Brooks 1992, pp. 76–80.

- June McDaniel 2004, pp. 89–91.

- June McDaniel 2004, p. 214.

- Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3.

- Jörg Breu d. Ä. zugeschrieben, Idol von Calicut, in: Ludovico de Varthema, 'Die Ritterlich und lobwürdig Reisz', Strassburg 1516. (Bild: Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich

- Laura Amazzone 2012, pp. 4–5.

- Chitrita Banerji 2006, pp. 3–5.

- Donald J LaRocca 1996, pp. 5–7.

- Linda Johnsen (2002). The Living Goddess: Reclaiming the Tradition of the Mother of the Universe. Yes International Publishers. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-936663-28-9.

- Laura Amazzone 2012, pp. 4–9, 14–17.

- Malcolm McLean 1998, pp. 60–65.

- Alf Hiltebeitel; Kathleen M. Erndl (2000). Is the Goddess a Feminist?: The Politics of South Asian Goddesses. New York University Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-8147-3619-7.

- Charles Russell Coulter & Patricia Turner 2013, p. 158.

- Linda Johnsen (2002). The Living Goddess: Reclaiming the Tradition of the Mother of the Universe. Yes International Publishers. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-936663-28-9.

- Alf Hiltebeitel; Kathleen M. Erndl (2000). Is the Goddess a Feminist?: The Politics of South Asian Goddesses. New York University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-8147-3619-7.

- David Kinsley 1988, pp. 95–105.

- David Kinsley 1997, pp. 30–35, 60, 16–22, 149.

- Patricia Monaghan 2011, pp. 73–74.

- Patricia Monaghan 2011, pp. 73–78.

- J Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 239–241. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- David Kinsley 1988, pp. 106–108.

- David Kinsley 1997, pp. 18–19.

- Rachel Fell McDermott 2001, pp. 172–174.

- Lynn Foulston & Stuart Abbott 2009, pp. 162–169.

- Esposito, John L.; Darrell J Fasching; Todd Vernon Lewis (2007). Religion & globalization: world religions in historical perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-19-517695-7.

- "Article on Durga Puja". Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- Kinsley, David (1988) Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06339-2 p. 95

- Joanne Punzo Waghorne (2004). Diaspora of the Gods: Modern Hindu Temples in an Urban Middle-Class World. Oxford University Press. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0-19-803557-2.

- Miranda Eberle Shaw (2006). Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 0-691-12758-1.

- Hajime Nakamura (1980). Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 315. ISBN 978-81-208-0272-8.

- Shoko Watanabe (1955), On Durga and Tantric Buddhism, Chizan Gakuho, number 18, pages 36-44

- Louis-Frédéric (1995). Buddhism. Flammarion. p. 174. ISBN 978-2-08-013558-2.

- Bernard Faure (2009). The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender. Princeton University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1400825615.

- Lawrence A. Babb (1998). Ascetics and kings in a Jain ritual culture. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 146–147, 157. ISBN 978-81-208-1538-4.

- Lisa Owen (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-90-04-20630-4.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-19-106277-3.

- John N. Miksic (2007). Icons of Art: The Collections of the National Museum of Indonesia. BAB Pub. Indonesia. pp. 106, 224–238. ISBN 978-979-8926-25-9.

- Ann R Kinney; Marijke J Klokke; Lydia Kieven (2003). Worshiping Siva and Buddha: The Temple Art of East Java. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 131–145. ISBN 978-0-8248-2779-3.

- Roy E Jordaan; Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Netherlands) (1996). In praise of Prambanan: Dutch essays on the Loro Jonggrang temple complex. KITLV Press. pp. 147–149. ISBN 978-90-6718-105-1.

- Trudy Jacobsen (2008). Lost Goddesses: The Denial of Female Power in Cambodian History. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press. pp. 20–21 with figure 2.2. ISBN 978-87-7694-001-0.

- Heidi Tan (2008). Vietnam: from myth to modernity. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum. pp. 56, 62–63. ISBN 978-981-07-0012-6.

- Catherine Noppe; Jean-François Hubert (2003). Art of Vietnam. Parkstone. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-85995-860-5.

- "Durga Puja – Hindu festival". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2015.

- Sabyasachi Bhattacharya (2003). Vande Mataram, the Biography of a Song. Penguin. pp. 5, 90–99. ISBN 978-0-14-303055-3.

- Sumathi Ramaswamy (2009). The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India. Duke University Press. pp. 106–108. ISBN 978-0-8223-9153-1.

Bibliography

- Laura Amazzone (2012). Goddess Durga and Sacred Female Power. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-5314-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laura Amazzone (2011). Patricia Monaghan (ed.). Goddesses in World Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35465-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chitrita Banerji (2006). The Hour of the Goddess: Memories of Women, Food, and Ritual in Bengal. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-400142-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Douglas Renfrew Brooks (1992). Auspicious Wisdom. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1145-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- C Mackenzie Brown (1990). The Triumph of the Goddess: The Canonical Models and Theological Visions of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0364-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cheever Mackenzie Brown (1998). The Devi Gita: The Song of the Goddess: A Translation, Annotation, and Commentary. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3939-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas B. Coburn (1991). Encountering the Goddess: A translation of the Devi-Mahatmya and a Study of Its Interpretation. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0446-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas B. Coburn (2002). Devī Māhātmya, The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition. South Asia Books. ISBN 81-208-0557-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charles Russell Coulter; Patricia Turner (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-96397-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paul Reid-Bowen (2012). Denise Cush; Catherine Robinson; Michael York (eds.). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-18979-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robert S Ellwood; Gregory D Alles (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1038-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lynn Foulston; Stuart Abbott (2009). Hindu Goddesses: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-902210-43-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Constance Jones; James D Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- David R Kinsley (1989). The Goddesses' Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- David Kinsley (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- David Kinsley (1997). Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91772-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donald J LaRocca (1996). The Gods of War: Sacred Imagery and the Decoration of Arms and Armor. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-779-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James G Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- June McDaniel (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534713-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rachel Fell McDermott (2001). Mother of My Heart, Daughter of My Dreams: Kali and Uma in the Devotional Poetry of Bengal. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803071-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malcolm McLean (1998). Devoted to the Goddess: The Life and Work of Ramprasad. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3689-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patricia Monaghan (2011). Goddesses in World Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35465-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sree Padma (2014). Inventing and Reinventing the Goddess: Contemporary Iterations of Hindu Deities on the Move. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-9002-9.

- Charles Phillips; Michael Kerrigan; David Gould (2011). Ancient India's Myths and Beliefs. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4488-5990-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ludo Rocher (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447025225.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sen Ramprasad (1720–1781). Grace and Mercy in Her Wild Hair: Selected Poems to the Mother Goddess. Hohm Press. ISBN 0-934252-94-7.

- Hillary Rodrigues (2003). Ritual Worship of the Great Goddess: The Liturgy of the Durga Puja with Interpretations. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8844-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Durga - Hindu mythology". Encyclopedia Britannica. 19 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

External links

- Durga Battling the Buffalo Demon: Iconography, Carlos Museum, Emory University

- Devi Durga, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Overview Of World Religions – Devotion to Durga