Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (commonly referred to as Dodd–Frank) is a United States federal law that was enacted on July 21, 2010.[1] The law overhauled financial regulation in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and it made changes affecting all federal financial regulatory agencies and almost every part of the nation's financial services industry.

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act to promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system, to end "too big to fail", to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts, to protect consumers from abusive financial services practices, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Dodd–Frank Act |

| Enacted by | the 111th United States Congress |

| Effective | July 21, 2010 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 111–203 |

| Statutes at Large | 124 Stat. 1376–2223 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Commodity Exchange Act Consumer Credit Protection Act Federal Deposit Insurance Act Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 Federal Reserve Act Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 International Banking Act of 1978 Protecting Tenants at Foreclosure Act Revised Statutes of the United States Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Truth in Lending Act |

| Titles amended | 12 U.S.C.: Banks and Banking 15 U.S.C.: Commerce and Trade |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act | |

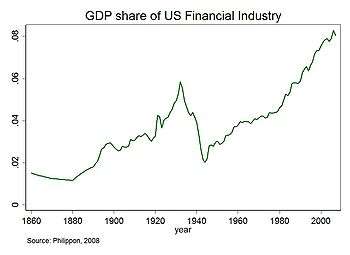

Responding to widespread calls for changes to the financial regulatory system, in June 2009 President Barack Obama introduced a proposal for a "sweeping overhaul of the United States financial regulatory system, a transformation on a scale not seen since the reforms that followed the Great Depression". Legislation based on his proposal was introduced in the United States House of Representatives by Congressman Barney Frank, and in the United States Senate by Senator Chris Dodd. Most congressional support for Dodd-Frank came from members of the Democratic Party, but three Senate Republicans voted for the bill, allowing it to overcome the Senate filibuster.

Dodd-Frank reorganized the financial regulatory system, eliminating the Office of Thrift Supervision, assigning new responsibilities to existing agencies like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and creating new agencies like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB was charged with protecting consumers against abuses related to credit cards, mortgages, and other financial products. The act also created the Financial Stability Oversight Council and the Office of Financial Research to identify threats to the financial stability of the United States, and gave the Federal Reserve new powers to regulate systemically important institutions. To handle the liquidation of large companies, the act created the Orderly Liquidation Authority. One provision, the Volcker Rule, restricts banks from making certain kinds of speculative investments. The act also repealed the exemption from regulation for security-based swaps, requiring credit-default swaps and other transactions to be cleared through either exchanges or clearinghouses. Other provisions affect issues such as corporate governance, 1256 Contracts, and credit rating agencies.

Dodd-Frank is generally regarded as one of the most significant laws enacted during the presidency of Barack Obama.[2] Studies have found the Dodd–Frank Act has improved financial stability and consumer protection,[3] although there has been debate regarding its economic effects.[4][5] In 2017, Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen stated that "the balance of research suggests that the core reforms we have put in place have substantially boosted resilience without unduly limiting credit availability or economic growth." Some critics have argued that the law had a negative impact on economic growth and small banks, or failed to provide adequate regulation to the financial industry. Many Republicans have called for the partial or total repeal of the law.

Origins and proposal

The financial crisis of 2007–10 led to widespread calls for changes in the regulatory system.[7] In June 2009, President Obama introduced a proposal for a "sweeping overhaul of the United States financial regulatory system, a transformation on a scale not seen since the reforms that followed the Great Depression".[8]

As the finalized bill emerged from conference, President Obama said that it included 90 percent of the reforms he had proposed.[9] Major components of Obama's original proposal, listed by the order in which they appear in the "A New Foundation" outline,[8] include

- The consolidation of regulatory agencies, elimination of the national thrift charter, and new oversight council to evaluate systemic risk

- Comprehensive regulation of financial markets, including increased transparency of derivatives (bringing them onto exchanges)

- Consumer protection reforms including a new consumer protection agency and uniform standards for "plain vanilla" products as well as strengthened investor protection

- Tools for financial crisis, including a "resolution regime" complementing the existing Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) authority to allow for orderly winding down of bankrupt firms, and including a proposal that the Federal Reserve (the "Fed") receive authorization from the Treasury for extensions of credit in "unusual or exigent circumstances"

- Various measures aimed at increasing international standards and cooperation including proposals related to improved accounting and tightened regulation of credit rating agencies

At President Obama's request, Congress later added the Volcker Rule to this proposal in January 2010.[10]

Legislative response and passage

The bills that came after Obama's proposal were largely consistent with the proposal, but contained some additional provisions and differences in implementation.[11]

The Volcker Rule was not included in Obama's initial June 2009 proposal, but Obama proposed the rule[10] later in January 2010, after the House bill had passed. The rule, which prohibits depository banks from proprietary trading (similar to the prohibition of combined investment and commercial banking in the Glass–Steagall Act[12]), was passed only in the Senate bill,[11] and the conference committee enacted the rule in a weakened form, Section 619 of the bill, that allowed banks to invest up to 3 percent of their tier 1 capital in private equity and hedge funds[13] as well as trade for hedging purposes.

On December 2, 2009, revised versions of the bill were introduced in the House of Representatives by then–financial services committee chairman Barney Frank, and in the Senate Banking Committee by former chairman Chris Dodd.[14] The initial version of the bill passed the House largely along party lines in December by a vote of 223 to 202,[15] and passed the Senate with amendments in May 2010 with a vote of 59 to 39[15] again largely along party lines.[15]

The bill then moved to conference committee, where the Senate bill was used as the base text[16] although a few House provisions were included in the bill's base text.[17] The final bill passed the Senate in a vote of 60-to-39, the minimum margin necessary to defeat a filibuster. Olympia Snowe, Susan Collins, and Scott Brown were the only Republican senators who voted for the bill, while Russ Feingold was the lone Senate Democrat to vote against the bill.[18]

One provision on which the White House did not take a position[19] and remained in the final bill[19] allows the SEC to rule on "proxy access"—meaning that qualifying shareholders, including groups, can modify the corporate proxy statement sent to shareholders to include their own director nominees, with the rules set by the SEC. This rule was unsuccessfully challenged in conference committee by Chris Dodd, who—under pressure from the White House[20]—submitted an amendment limiting that access and ability to nominate directors only to single shareholders who have over 5 percent of the company and have held the stock for at least two years.[19]

The "Durbin amendment"[21] is a provision in the final bill aimed at reducing debit card interchange fees for merchants and increasing competition in payment processing. The provision was not in the House bill;[11] it began as an amendment to the Senate bill from Dick Durbin[22] and led to lobbying against it.[23]

The New York Times published a comparison of the two bills prior to their reconciliation.[24] On June 25, 2010, conferees finished reconciling the House and Senate versions of the bills and four days later filed a conference report.[15][25] The conference committee changed the name of the Act from the "Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2010". The House passed the conference report, 237–192 on June 30, 2010.[26] On July 15, the Senate passed the Act, 60–39.[27][28] President Obama signed the bill into law on July 21, 2010.[29]

Repeal efforts

Since the passage of Dodd-Frank, many Republicans have called for a partial or total repeal of Dodd-Frank.[30] On June 9, 2017, The Financial Choice Act, legislation that would "undo significant parts" of Dodd-Frank, passed the House 233–186.[31][32][33][34][35]

On March 14, 2018, the Senate passed the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act exempting dozens of U.S. banks from the Dodd–Frank Act's banking regulations.[36] On May 22, 2018, the law passed in the House of Representatives.[37] On May 24, 2018, President Trump signed the partial repeal into law.[38]

Overview

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act is categorized into 16 titles and, by one law firm's count, it requires that regulators create 243 rules, conduct 67 studies, and issue 22 periodic reports.[39]

The stated aim of the legislation is

To promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system, to end "too big to fail," to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts, to protect consumers from abusive financial services practices, and for other purposes.[40]

The Act changes the existing regulatory structure, by creating a number of new agencies (while merging and removing others) in an effort to streamline the regulatory process, increasing oversight of specific institutions regarded as a systemic risk, amending the Federal Reserve Act, promoting transparency, and additional changes. The Act's intentions are to provide rigorous standards and supervision to protect the economy and American consumers, investors and businesses; end taxpayer-funded bailouts of financial institutions; provide for an advanced warning system on the stability of the economy; create new rules on executive compensation and corporate governance; and eliminate certain loopholes that led to the 2008 economic recession.[41] The new agencies are either granted explicit power over a particular aspect of financial regulation, or that power is transferred from an existing agency. All of the new agencies, and some existing ones that are not currently required to do so, are also compelled to report to Congress on an annual (or biannual) basis, to present the results of current plans and explain future goals. Important new agencies created include the Financial Stability Oversight Council, the Office of Financial Research, and the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection.

Of the existing agencies, changes are proposed, ranging from new powers to the transfer of powers in an effort to enhance the regulatory system. The institutions affected by these changes include most of the regulatory agencies currently involved in monitoring the financial system (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Federal Reserve (the "Fed"), the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), etc.), and the final elimination of the Office of Thrift Supervision (further described in Title III—Transfer of Powers to the Comptroller, the FDIC, and the FED).

As a practical matter, prior to the passage of Dodd–Frank, investment advisers were not required to register with the SEC if the investment adviser had fewer than 15 clients during the previous 12 months and did not hold himself out generally to the public as an investment adviser. The act eliminates that exemption, rendering numerous additional investment advisers, hedge funds, and private equity firms subject to new registration requirements.[42]

Certain nonbank financial institutions and their subsidiaries will be supervised by the Fed[43] in the same manner and to the same extent as if they were a bank holding company.[44]

To the extent that the Act affects all federal financial regulatory agencies, eliminating one (the Office of Thrift Supervision) and creating two (Financial Stability Oversight Council and the Office of Financial Research) in addition to several consumer protection agencies, including the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection, this legislation in many ways represents a change in the way America's financial markets will operate in the future. Few provisions of the Act became effective when the bill was signed.[45]

Provisions

Title I – Financial Stability

Title I, or the "Financial Stability Act of 2010,"[46] outlines two new agencies tasked to monitor systemic risk and research the state of the economy and clarifies the comprehensive supervision of bank holding companies by the Federal Reserve.

Title I creates the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) and the Office of Financial Research (OFR) in the U.S. Treasury Department. These two agencies are designed to work closely together. The council is formed of 10 voting members, 9 of whom are federal regulators and 5 nonvoting supporting members, to encourage interagency collaboration and knowledge transfer.[47] The treasury secretary is chairman of the council, and the head of the Financial Research Office is appointed by the president with confirmation from the Senate.

Title I introduced the ability to impose stricter regulations on certain institutions by classifying them as SIFI's (systemically important financial institutions); according to Paul Krugman, this has resulted in institutions reducing risk to avoid such classification.[48]

Under section 165d, certain institutions must prepare resolution plans (so-called living wills), the first round of which was rejected by the Federal Reserve System in 2014.[49] The process can be seen as a way to regulate and reduce shadow banking activities by banking institutions.[50]

Financial Stability Oversight Council

The Financial Stability Oversight Council is tasked to identify threats to the financial stability of the United States, promote market discipline, and respond to emerging risks in order to stabilize the United States financial system. At a minimum, it must meet quarterly.

The Council is required to report to Congress on the state of the financial system and may direct the Office of Financial Research to conduct research.[51] Notable powers include

- With a two-thirds vote, it may place nonbank financial companies or domestic subsidiaries of international banks under the supervision of the Federal Reserve if it appears that these companies could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States.[52]

- Under certain circumstances, the council may provide for more stringent regulation of a financial activity by issuing recommendations to the primary financial regulatory agency, which the primary financial agency is obliged to implement—the council reports to Congress on the implementation or failure to implement such recommendations.[53]

- The council may require any bank or nonbank financial institution with assets over $50 billion to submit certified financial reports.[54]

- With the approval of the council, the Federal Reserve may promulgate safe harbor regulations to exempt certain types of foreign banks from regulation.[55]

Office of Financial Research

The Office of Financial Research is designed to support the Financial Stability Oversight Council through data collection and research. The director has subpoena power and may require from any financial institution (bank or nonbank) any data needed to carry out the functions of the office.[56] The Office can also issue guidelines to standardizing the way data is reported; constituent agencies have three years to implement data standardization guidelines.[57]

It is intended to be self-funded through the Financial Research Fund within two years of enactment, with the Federal Reserve providing funding in the initial interim period.[58]

In many ways, the Office of Financial Research is to be operated without the constraints of the Civil Service system. For example, it does not need to follow federal pay-scale guidelines (see above), and it is mandated that the office have workforce development plans[59] that are designed to ensure that it can attract and retain technical talent, which it is required to report about congressional committees for its first five years.[60]

Title II—Orderly Liquidation Authority

Before Dodd–Frank, federal laws to handle the liquidation and receivership of federally regulated banks existed for supervised banks, insured depository institutions, and securities companies by the FDIC or Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC). Dodd–Frank expanded these laws to potentially handle insurance companies and nonbank financial companies and changed these liquidation laws in certain ways.[61] Once it is determined that a financial company satisfied the criteria for liquidation, if the financial company's board of directors does not agree, provisions are made for judicial appeal.[62] Depending on the type of financial institution, different regulatory organizations may jointly or independently, by two-thirds vote, determine whether a receiver should be appointed for a financial company:[63]

- In General—FDIC and/or the Federal Reserve

- Broker Dealers—SEC and/or the Federal Reserve

- Insurance Companies—Federal Insurance Office (part of the Treasury Department and established in this Act) and/or the Federal Reserve

Provided that the secretary of treasury, in consultation with the president, may also determine to appoint a receiver for a financial company.[64] Also, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) shall review and report to Congress about the secretary's decision.[65]

When a financial institution is placed into receivership under these provisions, within 24 hours, the secretary shall report to Congress. Also, within 60 days, there shall be a report to the general public.[66] The report on recommending to place a financial company into receivership shall contain various details on the state of the company, the impact of its default on the company, and the proposed action.[67]

FDIC liquidation

Unless otherwise stated, the FDIC is the liquidator for financial institutions who are not banking members (such as the SIPC) nor insurance companies (such as the FDIC). In taking action under this title, the FDIC shall comply with various requirements:[68]

- Determine that such action is necessary for purposes of the financial stability of the United States, and not for the purpose of preserving the covered financial company

- Ensure that the shareholders of a covered financial company do not receive payment until after all other claims and the Funds are fully paid

- Ensure that unsecured creditors bear losses in accordance with the priority of claim provisions

- Ensure that management responsible for the failed condition of the covered financial company is removed (if such management has not already been removed at the time at which the corporation is appointed receiver)

- Ensure that the members of the board of directors (or body performing similar functions) responsible for the failed condition of the covered financial company are removed, if such members have not already been removed at the time the corporation is appointed as receiver

- Not take an equity interest in or become a shareholder of any covered financial company or any covered subsidiary

Orderly Liquidation Fund

To the extent that the Act expanded the scope of financial firms that may be liquidated by the federal government, beyond the existing authorities of the FDIC and SIPC, there had to be an additional source of funds, independent of the FDIC's Deposit Insurance Fund, used in case of a non-bank or non-security financial company's liquidation. The Orderly Liquidation Fund is to be an FDIC-managed fund, to be used by the FDIC in the event of a covered financial company's liquidation[69] that is not covered by FDIC or SIPC.[70]

Initially, the fund is to be capitalized over a period no shorter than five years, but no longer than 10; however, in the event the FDIC must make use of the fund before it is fully capitalized, the secretary of the treasury and the FDIC are permitted to extend the period as determined necessary.[40] The method of capitalization is by collecting risk-based assessment fees on any "eligible financial company"—which is defined as ". . . any bank holding company with total consolidated assets equal to or greater than $50 billion and any nonbank financial company supervised by the Board of Governors." The severity of the assessment fees can be adjusted on an as-needed basis (depending on economic conditions and other similar factors), and the relative size and value of a firm is to play a role in determining the fees to be assessed.[40] The eligibility of a financial company to be subject to the fees is periodically reevaluated; or, in other words, a company that does not qualify for fees in the present will be subject to the fees in the future if it crosses the 50 billion line, or become subject to Federal Reserve scrutiny.[40]

To the extent that a covered financial company has a negative net worth and its liquidation creates an obligation to the FDIC as its liquidator, the FDIC shall charge one or more risk-based assessment such that the obligation will be paid off within 60 months of the issuance of the obligation.[71] The assessments will be charged to any bank holding company with consolidated assets greater than $50 billion and any nonbank financial company supervised by the Federal Reserve. Under certain conditions, the assessment may be extended to regulated banks and other financial institutions.[72]

Assessments will be implemented according to a matrix that the Financial Stability Oversight Council recommends to the FDIC. The matrix shall take into account[73]

- Economic conditions—higher assessments during more favorable economic conditions

- Whether the institution is

- An insured depositary institution that is a member of the FDIC

- A member of the SIPC

- An insured credit union

- An insurance company, assessed pursuant to applicable state law to cover costs of rehabilitation or liquidation

- Strength of its balance sheet, both on-balance sheet and off-balance sheet assets, and its leverage

- Relevant market share

- Potential exposure to sudden calls on liquidity precipitated by economic distress with other financial companies

- The amount, maturity, volatility, and stability of the liabilities of the company, including the degree of reliance on short-term funding, taking into consideration existing systems for measuring a company's risk-based capital

- The stability and variety of the company's sources of funding

- The company's importance as a source of credit for households, businesses, and state and local governments and as a source of liquidity for the financial system

- The extent to which assets are simply managed and not owned by the financial company and the extent to which ownership of assets under management is diffuse

- The amount, different categories, and concentrations of liabilities, both insured and uninsured, contingent and noncontingent, including both on-balance sheet and off-balance sheet liabilities, of the financial company and its affiliates

Obligation limit and funding

When liquidating a financial company under this title (as opposed to FDIC or SIPD) there is a maximum limit of the government's liquidation obligation, i.e., the government's obligation can not exceed[74]

- 10 percent of the total consolidated assets, or

- 90 percent of the fair value of the total consolidated assets

In the event that the Fund and other sources of capital are insufficient, the FDIC is authorized to buy and sell securities on behalf of the company (or companies) in receivership to raise additional capital.[40] Taxpayers shall bear no losses from liquidating any financial company under this title, and any losses shall be the responsibility of the financial sector, recovered through assessments:[75]

- Liquidation is required for all financial companies put into receivership under this title

- All funds expended in the liquidation of a financial company under this title shall be recovered from the disposition of assets or assessments on the financial sector

Orderly Liquidation Authority Panel

Established inside the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware, the panel is tasked with evaluating the conclusion of the secretary of treasury that a company is in (or in danger of) default. The panel consists of three bankruptcy judges drawn from the District of Delaware, all of whom are appointed by the chief judge of the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware. In his appointments, the chief judge is instructed to weigh the financial expertise of the candidates.[40] If the panel concurs with the secretary, the company in question is permitted to be placed into receivership; if it does not concur, the secretary has an opportunity to amend and refile his or her petition.[40] In the event that a panel decision is appealed, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has jurisdiction; in the event of further appeal, a writ of certiorari may be filed with the U.S. Supreme Court. In all appellate events, the scope of review is limited to whether the decision of the secretary that a company is in (or in danger of) default is supported by substantial evidence.[40]

Title III—Transfer of Powers to the Comptroller, the FDIC, and the Fed

Title III, or the "Enhancing Financial Institution Safety and Soundness Act of 2010,"[76] is designed to streamline banking regulation. It also is intended to reduce competition and overlaps between different regulators by abolishing the Office of Thrift Supervision and transferring its power over the appropriate holding companies to the board of governors of the Federal Reserve System, state savings associations to the FDIC, and other thrifts to the office of the Comptroller of the Currency.[77] The thrift charter is to remain, although weakened. Additional changes include:

- The amount of deposits insured by the FDIC and the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (NCUSIF) is permanently increased from $100,000 to $250,000.[78][79]

- Each of the financial regulatory agencies represented on the Council shall establish an Office of Minority and Women Inclusion that shall be responsible for all matters of the agency in relation to diversity in management, employment, and business activities.[80]

Title IV—Regulation of Advisers to Hedge Funds and Others

Title IV, or the "Private Fund Investment Advisers Registration Act of 2010,"[81] requires certain previously exempt investment advisers to register as investment advisers under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.[82] Most notably, it requires many hedge fund managers and private equity fund managers to register as advisers for the first time.[83] Also, the act increases the reporting requirements of investment advisers as well as limiting these advisers' ability to exclude information in reporting to many of the federal government agencies.

Title V—Insurance

Title V—Insurance is split into two subtitles: A.) Federal Insurance Office, and B.) State-Based Insurance Reform.

Subtitle A—Federal Insurance Office

Subtitle A, also called the "Federal Insurance Office Act of 2010",[84] establishes the Federal Insurance Office within the Treasury Department, which is tasked with:[85]

- Monitoring all aspects of the insurance industry (except health insurance, some long-term care insurance, and crop insurance), including the identification of gaps in regulation of insurers that could contribute to financial crisis[86]

- Monitoring the extent to which traditionally under-served communities and consumers, minorities, and low-and moderate-income persons have access to affordable insurance (except health insurance)

- Making recommendations to the Financial Stability Oversight Council about insurers that may pose a risk, and to help any state regulators with national issues

- Administering the Terrorism Insurance Program

- Coordinating international insurance matters

- Determining whether state insurance measure are preempted by covered agreements (states may have more stringent requirements)

- Consulting with the states (including state insurance regulators) regarding insurance matters of national importance and prudential insurance matters of international importance;

The office is headed by a director appointed for a career-reserved term by the secretary of the treasury.[87]

Generally, the Insurance Office may require any insurer company to submit such data as may be reasonably required in carrying out the functions of the office.[88]

A state insurance measure shall be preempted if, and only to the extent that, the director determines that the measure results in a less favorable treatment of a non–U.S. insurer whose parent corporation is located in a nation with an agreement or treaty with the United States.[89]

Subtitle B—State-Based Insurance Reform

Subtitle B, also called the "Nonadmitted and Reinsurance Reform Act of 2010"[90] applies to nonadmitted insurance and reinsurance. Regarding to nonadmitted insurance, the Act provides that the placement of nonadmitted insurance will be subject only to the statutory and regulatory requirements of the insured's home state and that no state, other than the insured's home state, may require a surplus lines broker to be licensed to sell, solicit, or negotiate nonadmitted insurance respecting the insured.[91] The Act also provides that no state, other than the insured's home state, may require any premium tax payment for nonadmitted insurance.[92] However, states may enter into a compact or otherwise establish procedures to allocate among the states the premium taxes paid to an insured's home state.[93] A state may not collect any fees in relation to the licensing of an individual or entity as a surplus lines broker in the state unless that state has in effect by July 21, 2012, laws or regulations providing for participation by the state in the NAIC's national insurance producer database, or any other equivalent uniform national database, for the licensure of surplus lines brokers and the renewal of these licenses.[94]

Title VI—Improvements to Regulation

Provisions

Title VI, or the "Bank and Savings Association Holding Company and Depository Institution Regulatory Improvements Act of 2010,"[95] introduces the so-called Volcker Rule after former chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker by amending the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956. With aiming to reduce the amount of speculative investments on the balance sheets of large firms, it limits banking entities to owning no more than 3 percent in a hedge fund or private equity fund of the total ownership interest.[96] All of the banking entity's interests in hedge funds or private equity funds cannot exceed 3 percent of the banking entity's Tier 1 capital. Furthermore, no bank with a direct or indirect relationship with a hedge fund or private equity fund "may enter into a transaction with the fund, or with any other hedge fund or private equity fund that is controlled by such fund" without disclosing the relationship's full extent to the regulating entity, and ensuring that there is no conflict of interest.[97] "Banking entity" includes an insured depository institution, any company controlling an insured depository institution, and such a company's affiliates and subsidiaries. Also, it must comply with the Act within two years of its passing, although it may apply for time extensions. Responding to the Volcker Rule and anticipating of its ultimate impact, several commercial banks and investment banks operating as bank holding companies have already begun downsizing or disposing their proprietary trading desks.[98]

The rule distinguishes transactions by banking entities from transactions by nonbank financial companies supervised by the Federal Reserve Board.[99] The rule states that generally "an insured depository institution may not purchase an asset from, or sell an asset to, an executive officer, director, or principal shareholder of the insured depository institution, or any related interest of such person . . . unless the transaction is on market terms; and if the transaction represents more than 10 percent of the capital stock and surplus of the insured depository institution, the transaction has been approved in advance by a majority of the members of the board of directors of the insured depository institution who do not have an interest in the transaction."[100] Providing for the regulation of capital, the Volcker Rule says that regulators are required to impose upon institutions capital requirements that are "countercyclical, so that the amount of capital required to be maintained by a company increases in times of economic expansion and decreases in times of economic contraction," to ensure the safety and soundness of the organization.[101][102] The rule also provides that an insured state bank may engage in a derivative transaction only if the law with respect to lending limits of the state in which the insured state bank is chartered takes into consideration credit exposure to derivative transactions.[103] The title provides for a three-year moratorium on approving FDIC deposit insurance received after November 23, 2009, for an industrial bank, a credit card bank, or a trust bank either directly or indirectly owned or controlled by a commercial firm.[104]

In accordance with section 1075 of the law, payment card networks must allow merchants to establish a minimum dollar amount for customers using payment cards, as long as the minimum is no higher than $10.[105]

Background

The Volcker Rule was first publicly endorsed by President Obama on January 21, 2010.[106][107] The final version of the Act prepared by the conference committee included a strengthened Volcker rule by containing language by Senators Jeff Merkley (D-Oregon) and Carl Levin (D-Michigan), covering a greater range of proprietary trading than originally proposed by the administration, except notably for trading in U.S. government securities and bonds issued by government-backed entities. The rule also bans conflict-of-interest trading.[101][108] The rule seeks to ensure that banking organizations are both well capitalized and well managed.[109] The proposed draft form of the Volcker Rule was presented by regulators for public comment on October 11, 2011, with the rule due to go into effect on July 21, 2012.[110]

Title VII—Wall Street Transparency and Accountability

Title VII, also called the Wall Street Transparency and Accountability Act of 2010,[111] concerns regulation of over the counter swaps markets.[112] This section includes the credit default swaps and credit derivative that were the subject of several bank failures c. 2007. Financial instruments have the means given the terms in section 1a of the Commodity Exchange Act (7 U.S.C. § 1a).[113] On a broader level, the Act requires that various derivatives known as swaps, which are traded over the counter, must be cleared through either exchanges or clearinghouses.[114]

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) both regulate derivatives known as swaps under the Act, but the SEC has authority over "security-based swaps." The Act repeals exemption from regulation for security-based swaps under the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act[115]:55 The regulators are required to consult with each other before implementing any rule-making or issuing orders regarding several different types of security swaps.[116] The CFTC and SEC, consultating with the Federal Reserve, are charged with further defining swap related terms that appear in Commodity Exchange Act (7 U.S.C. § 1a(47)(A)(v)) and section 3(a)(78) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. § 78c(a)(78)).[117]

The title provides that "except as provided otherwise, no Federal assistance may be provided to any swaps entity with respect to any swap, security-based swap, or other activity of the swaps entity."[118] An "Interagency Group" is constituted to handle the oversight of existing and prospective carbon markets to ensure an efficient, secure, and transparent carbon market, including oversight of spot markets and derivative markets.[119]

Title VIII—Payment, Clearing, and Settlement Supervision

Title VIII, called the Payment, Clearing, and Settlement Supervision Act of 2010,[120] aims to mitigate systemic risk within and promote stability in the financial system by tasking the Federal Reserve to create uniform standards for the management of risks by systemically important financial organizations and institutions by providing the Fed with an "enhanced role in the supervision of risk management standards for systemically important financial market utilities; strengthening the liquidity of systemically important financial market utilities; and providing the Board of Governors an enhanced role in the supervision of risk management standards for systemically important payment, clearing, and settlement activities by financial institutions."[121]

Title IX—Investor Protections and Improvements to the Regulation of Securities

Title IX, sections 901 to 991, known as the Investor Protections and Improvements to the Regulation of Securities,[122] revises the Securities and Exchange Commission's powers and structure, as well as credit rating organizations and the relationships between customers and broker-dealers or investment advisers. This title calls for various studies and reports from the SEC and Government Accountability Office (GAO). This title contains 10 subtitles, lettered A through J.

Subtitle A—Increasing Investor Protection

Subtitle A contains provisions

- To prevent regulatory capture within the SEC and increase the influence of investors, the Act creates an Office of the Investor Advocate,[123] an investor advisory committee composed of 12 to 22 members who serve four-year terms,[124] and an ombudsman appointed by the Office of the Investor Advocate.[125] The investor advisory committee was actually created in 2009 and, therefore, it predates the Act's passage. However, it is specifically authorized under the Act.[115]

- SEC is specifically authorized to issue "point-of-sale disclosure" rules when retail investors purchase investment products or services; these disclosures include concise information on costs, risks, and conflicts of interest.[115]:160–1 This authorization follows up the SEC's failure to implement proposed point-of-sale disclosure rules between 2004 and 2005.[126] These proposed rules generated opposition because they were perceived as burdensome to broker–dealers. For example, they would require oral disclosures for telephone transactions; they were not satisfied by cheap internet or email disclosures, and they could allow the customer to request disclosures specific to the amount of their investment. To determine the disclosure rules, the Act authorizes the SEC to perform "investor testing" and to rely on experts to study financial literacy among retail investors.[127]

Subtitle A provides authority for the SEC to impose regulations requiring "fiduciary duty" by broker–dealers to their customers.[115]:158 Although the Act does not create such a duty immediately, it does authorize the SEC to establish a standard. It also requires the SEC to study the standards of care that broker–dealers and investment advisers apply to their customers and to report to Congress on the results within six months.[115] Under the law, commission and limited product range would not violate the duty and broker–dealers would not have a continuing duty after receiving the investment advice.[128]

Subtitle B—Increasing Regulatory Enforcement and Remedies

Subtitle B gives the SEC further powers of enforcement, including a "whistleblower bounty program",[129] which is partially based upon the successful qui tam provisions of the 1986 Amendments to the False Claims Act as well as an IRS whistleblower reward program Congress created in 2006. The SEC program rewards individuals providing information resulting in an SEC enforcement action in which more than $1 million in sanctions is ordered.[72] Whistleblower rewards range from 10 to 30 percent of the recovery. The law also provides job protections for SEC whistleblowers and promises confidentiality for them.[130]

Section 921I controversially limited FOIA's applicability to the SEC,[131] a change partially repealed a few months later.[132] The SEC had previously used a narrower existing exemption for trade secrets when refusing Freedom of Information Requests.[133]

Subtitle C—Improvements to the Regulation of Credit Rating Agencies

Recognizing credit ratings that credit rating agencies had issued, including nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (NRSROs), are matters of national public interest, that credit rating agencies are critical "gatekeepers" in the debt market central to capital formation, investor confidence, and the efficient performance of the United States economy, Congress expanded regulation of credit rating agencies.[134]

Subtitle C cites findings of conflicts of interest and inaccuracies during the recent financial crisis contributed significantly to the mismanagement of risks by financial institutions and investors, which in turn adversely impacted the US economy as factors necessitating increased accountability and transparency by credit rating agencies.[135]

Subtitle C mandates the creation by the SEC of an Office of Credit Ratings (OCR) to provide oversight over NRSROs and enhanced regulation of such entities.[136]

Enhanced regulations of nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (NRSROs) include the following:

- Establish, maintain, enforce, and document an effective internal control structure governing the implementation of and adherence to policies, procedures, and methodologies for determining credit ratings.[137]

- Submit to the OCR an annual internal control report.

- Adhere to rules established by the Commission to prevent sales and marketing considerations from influencing the ratings issued by a NRSRO.

- Policies and procedures with regard to (1) certain employment transitions to avoid conflicts of interest, (2) the processing of complaints regarding NRSRO noncompliance, and (3) notification to users of identified significant errors are required.

- Compensation of the compliance officer may not be linked to the financial performance of the NRSRO.

- The duty to report to appropriate authorities credible allegations of unlawful conduct by issuers of securities.[137]

- The consideration of credible information about an issuer from sources other than the issuer or underwriter that is potentially significant to a rating decision.

- The Act establishes corporate governance, organizational, and management of conflict of interest guidelines. A minimum of 2 independent directors is required.[137]

Subtitle C grants the Commission some authority to either temporarily suspend or permanently revoke the registration of an NRSRO respecting a particular class or subclass of securities if after noticing and hearing that the NRSRO lacks the resources to produce credit ratings with integrity.[137] Additional key provisions of the Act are

- The Commission shall prescribe rules with respect to credit rating procedures and methodologies.

- OCR is required to conduct an examination of each NRSRO at least annually and shall produce a public inspection report.

- To facilitate transparency of credit ratings performance, the Commission shall require NRSROs to publicly disclose information on initial and revised credit ratings issued, including the credit rating methodology utilized and data relied on, to enable users to evaluate NRSROs.

Moreover, Subtitle C requires the SEC to conduct a study on strengthening the NRSRO's independence, and it recommends the organization to utilize its rule-making authority to establish guidelines preventing improper conflicts of interest arising from the performance of services unrelated to the issuance of credit ratings such as consulting, advisory, and other services.[138] The Act requires the comptroller general of the United States to conduct a study on alternative business models for compensating NRSROs[139]

Subtitle D—Improvements to the Asset-backed Securitization Process

In Subtitle D, the term "Asset-Backed Security" is defined as a fixed-income or other security collateralized by any self-liquidating financial asset, such as a loan, lease, mortgage, allowing the owner of the asset-backed security to receive payments depending on the cash flow of the (ex.) loan. For regulation purposes, asset-backed securities include (but are not limited to)[140]

- collateralized mortgage obligation

- collateralized debt obligation (CDOs)

- collateralized bond obligation

- collateralized debt obligation of asset-backed securities

- collateralized debt obligation of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs Squared)

The law required credit risk retention regulations (where 5% of the risk was retained) within nine months of enactment,.[141] Proposals had been highly criticized due to restrictive definitions on "qualified residential mortgages" with restrictive down-payment and debt-to-income requirements.[142] In the August 2013 proposal, the 20% down-payment requirement was dropped.[143] In October 2014, six federal agencies (Fed, OCC, FDIC, SEC, FHFA, and HUD) finalized their joint asset-backed securities rule.[144]

Regulations for assets that are

- Residential in nature are jointly prescribed by the SEC, the secretary of housing and urban development, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency

- In general, the federal banking agencies and the SEC

Specifically, securitizers are

- Prohibited from hedging or transferring the credit risk it is required to retain with respect to the assets

- Required to retain not less than 5 percent of the credit risk for an asset that is not a qualified residential mortgage,[145]

- For commercial mortgages or other types of assets, regulations may provide for retention of less than 5 percent of the credit risk, provided that there is also disclosure

The regulations are to prescribe several asset classes with separate rules for securitizers, including (but not limited to) residential mortgages, commercial mortgages, commercial loans, and auto loans. Both the SEC and the federal banking agencies may jointly issue exemptions, exceptions, and adjustments to the rules issues provided that they[146]

- Help ensure high-quality underwriting standards for the securitizers and originators of assets that are securitized or available for securitization

- Encourage appropriate risk management practices by the securitizers and originators of assets, improve the access of consumers and businesses to credit on reasonable terms, or otherwise be in the public interest and for the protection of investors

Additionally, the following institutions and programs are exempt:

- Farm Credit System

- Qualified Residential Mortgages (which are to be jointly defined by the federal banking agencies, SEC, secretary of housing and urban development, and the director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency)

The SEC may classify issuers and prescribe requirements appropriate for each class of issuers of asset-backed securities.[147] The SEC must also adopt regulations requiring each issuer of an asset-backed security to disclose, for each tranche or class of security, information that will help identify each asset backing that security.[148] Within six months of enactment, the SEC must issue regulations prescribing representations and warranties in the marketing of asset-backed securities:[149]

- Require each Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization to include in any report accompanying a credit rating a description of:

- The representations, warranties, and enforcement mechanisms available to investors

- How they differ from the representations, warranties, and enforcement mechanisms in issuances of similar securities

- Require any securitizer to disclose fulfilled and unfulfilled repurchase requests across all trusts aggregated by the securitizer, so that investors may identify asset originators with clear underwriting deficiencies

The SEC shall also prescribe a due diligence analysis/review of the assets underlying the security, and a disclosure of that analysis.

Subtitle E—Accountability and Executive Compensation

Within one year of enactment, the SEC must issue rules directing the national securities exchanges and associations to prohibit the listing of any security of an issuer not in compliance of the requirements of the compensation sections.[150] At least once every three years, a public corporation is required to submit the approval of executive compensation to a shareholder vote. And once every six years, there should be a submitted to shareholder vote whether the required approval of executive compensation should be usually that once every three years.[151] Shareholders may disapprove any Golden Parachute compensation to executives via a non-binding vote.[152] Shareholders must be informed of the relationship between executive compensation actually paid and the financial performance of the issuer, taking into account any change in the value of the shares of stock and dividends of the issuer and any distributions[153] as well as[154]

- The median of the annual total compensation of all employees of the issuer, except the chief executive officer (or any equivalent position)

- The annual total compensation of the chief executive officer, or any equivalent position

- The ratio of the amount of the median of the annual total with the total CEO compensation

The company must also disclose to shareholders whether any employee or member of the board of directors is permitted to purchase financial instruments designed to hedge or offset any decrease in the market value of equity securities that are part of a compensation package.[155] Members of the board of director's compensation committee have to be independent in the board of directors, a compensation consultant or legal counsel, as provided by rules issued by the SEC.[156] Within 9 months of enacting this legislation, federal regulators shall proscribe regulations that a covered company must disclose to the appropriate federal regulator, all incentive-based compensation arrangements with sufficient information such that the regulator may determine[157]

- Whether the compensation package could lead to material financial loss to the company

- Provides the employee/officer with excessive compensation, fees, or benefits

Subtitle F—Improvements to the Management of the Securities and Exchange Commission

Subtitle F contains various managerial changes intended to increase and implement the agency's efficiency, including reports on internal controls, a triennial report on personnel management by the head of the GAO (the Comptroller General of the United States), a hotline for employees to report problems in the agency, a report by the GAO on the oversight of National Securities Associations, and a report by a consultant on reform of the SEC. Under Subtitle J, the SEC will be funded through "match funding," which will in effect mean that its budget will be funded through filing fees.[115]:81

Subtitle G—Strengthening Corporate Governance

Subtitle G provides the SEC to issue rules and regulations including a requirement permitting a shareholder to use a company's proxy solicitation materials for nominating individuals to membership on the board of directors.[158] The company is also required to inform investors regarding why the same person is to serve as the board of directors' chairman and its chief executive officer, or the reason that different individuals must serve as the board's chairman or CEO.[159]

Subtitle H – Municipal Securities

This provision of the statute creates a guarantee of trust correlating a municipal adviser (who provides advice to state and local governments regarding investments)[160] with any municipal bodies providing services. Also, it alters the make-up of the Municipal Securities rulemaking board ("MSRB") and mandates that the comptroller general conduct studies in relation to municipal disclosure and municipal markets. The new MSRB will be composed of 15 individuals. Also, it will have the authority to regulate municipal advisers and will be permitted to charge fees regarding trade information. Furthermore, it is mandated that the comptroller general make several recommendations, which must be submitted to Congress within 24 months of enacting the law.[160][161]

Subtitle I—Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, Portfolio Margining, and Other Matters

Subtitle I is concerned with establishing a public company accounting oversight board (PCAOB). The PCAOB has the authority to establish oversight of certified public accounting firms. Its provision allows the SEC to authorize necessary rules respecting securities for borrowing. The SEC shall, as deemed appropriate, exercise transparency within this sector of the financial industry.[162] A council of inspectors general on financial oversight, composed of several members of federal agencies (such as the Department of the Treasury, the FDIC, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency) will be established.[163] The council will more easily allow the sharing of data with inspectors general (which includes members by proxy or in person from the SEC and CFTC) with a focus on dealings that may be applicable to the general financial sector largely focusing on the financial oversight's improvement.[164]

Subtitle J—Securities and Exchange Commission Match Funding

Subtitle J provides adjustments to Section 31 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 regarding the "Recovery Cost of Annual Appropriation," the "Registration of Fees" and the "Authorization of Appropriations" provisions of the Act.

Title X—Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection

Title X, or the "Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010",[165] establishes the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection. The new Bureau regulates consumer financial products and services in compliance with federal law.[40] The Bureau is headed by a director appointed by the President, with advice and consent from the Senate, for five-year term.[40] The Bureau is subject to financial audit by the GAO, and must report to the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee bi-annually. The Financial Stability Oversight Council may issue a "stay" to the Bureau with an appealable 2/3 of the vote. The Bureau is not placed within the Fed, but instead operates independently.[166] The Fed is prohibited from interfering with matters before the Director, directing any employee of the Bureau, modifying the Bureau's functions and responsibilities or impeding an order of the Bureau.[40] The Bureau is separated into six divisions:[40]

- Supervision, Enforcement, and Fair Lending

- Research, Markets, and Regulations

- Office of the Chief Operating Officer

- General Counsel

- Consumer Education and Engagement

- External Affairs.[167]

Within the Bureau, a new Consumer Advisory Board assists the Bureau and informs it of emerging market trends.[40] This Board is appointed by the Bureau's Director, with at least six members recommended by regional Fed Presidents.[40] Elizabeth Warren was the first appointee of the President as an adviser to get the Bureau operating. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau can be found on the web.

The Bureau was formally established when Dodd–Frank was enacted, on July 21, 2010. After a one-year "stand up" period, the Bureau obtained enforcement authority and began most activities on July 21, 2011.[168]

The Durbin Amendment targeting interchange fees is also in Title X, under Subtitle G, section 1075.[169]

Title XI – Federal Reserve System Provisions

Governance and oversight

A new position is created on the Board of Governors, the "Vice Chairman for Supervision", to advise the Board in several areas and[170]

- Serves in the absence of the chairman

- Is responsible for developing policy recommendations to the Board regarding supervision and regulation of financial institution supervised by the board

- Oversees the supervision and regulation of such firms

- Reports to Congress on a semiannual basis to disclose their activities and efforts, testifying before Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs of the Senate and the Committee on Financial Services of the House of Representatives

Additionally, the GAO is now required to perform several different audits of the Fed:[170]

- A one-time audit of any emergency lending facility established by the Fed since December 1, 2007 and ending with the date of enactment of this Act

- A Federal Reserve Governance Audit that shall examine:

- The extent to which the current system of appointing Federal reserve bank directors represents "the public, without discrimination on the basis of race, creed, color, sex or national origin, and with due but not exclusive consideration to the interests of agriculture, commerce, industry, services, labor, and consumers"

- Whether there are actual or potential conflicts of interest

- Examine each facilities operation

- Identify changes to selection procedures for Federal reserve bank directors or to other aspects of governance that would improve public representation and increase the availability of monetary information

Standards, plans & reports, and off-balance-sheet activities

The Fed is required to establish prudent standards for the institutions they supervise that include:[171]

- Risk-Based Capital Requirements and Leverage Limits

- Liquidity requirements;

- Resolution plan and credit exposure report requirements;[172]

- Overall risk management requirements; and

- Concentration limits.

The Fed may establish additional standards that include, but are not limited to

- A contingent capital requirement

- Enhanced public disclosure

- Short-term debt limits

The Fed may require supervised companies to "maintain a minimum amount of contingent capital that is convertible to equity in times of financial stress".[173]

Title XI requires companies supervised by the Fed to periodically provide additional plans and reports, including:"[174]

- A plan for a rapid and orderly liquidation of the company in the event of material financial distress or failure,

- A credit exposure report describing the nature to which the company has exposure to other companies, and credit exposure cannot exceed 25% of the capital stock and surplus of the company."[175]

The title requires that in determining capital requirements for regulated organizations, off-balance-sheet activities shall be taken into consideration, being those things that create an accounting liability such as, but not limited to"[176]

- Direct credit substitutes in which a bank substitutes its own credit for a third party, including standby letters of credit

- Irrevocable letters of credit that guarantee repayment of commercial paper or tax-exempt securities

- Risk participations in bankers' acceptances

- Sale and repurchase agreements

- Asset sales with recourse against the seller

- Interest rate swaps

- Credit swaps

- Commodities contracts

- Forward contracts

- Securities contracts

Title XII—Improving Access to Mainstream Financial Institutions

Title XII, known as the "Improving Access to Mainstream Financial Institutions Act of 2010",[177] provides incentives that encourage low- and medium-income people to participate in the financial systems. Organizations that are eligible to provide these incentives are 501(c)(3) and IRC § 501(a) tax exempt organizations, federally insured depository institutions, community development financial institutions, state, local or tribal governments.[178] Multi-year programs for grants, cooperative agreements, etc., are also available to[179]

- Enable low- and moderate-income individuals to establish one or more accounts in a federal insured bank

- Make micro loans, typically under $2,500

- Provide financial education and counseling

Title XIII—Pay It Back Act

Title XIII, or the "Pay It Back Act",[122] amends the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 to limit the Troubled Asset Relief Program, by reducing the funds available by $225 billion (from $700 billion to $475 billion) and further mandating that unused funds cannot be used for any new programs.[180]

Amendments to the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 and other sections of the federal code to specify that any proceeds from the sale of securities purchased to help stabilize the financial system shall be[181]

- Dedicated for the sole purpose of deficit reduction

- Prohibited from use as an offset for other spending increases or revenue reductions

The same conditions apply for any funds not used by the state under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 by December 31, 2012, provided that the President may waive these requirements if it is determined to be in the best interest of the nation.[182]

Title XIV—Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act

Title XIV, or the "Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act",[183] whose subtitles A, B, C, and E are designated as Enumerated Consumer Law, which will be administered by the new Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection.[184] The section focuses on standardizing data collection for underwriting and imposes obligations on mortgage originators to only lend to borrowers who are likely to repay their loans.

Subtitle A—Residential Mortgage Loan Organization Standards

A "Residential Mortgage Originator" is defined as any person who either receives compensation for or represents to the public that they will take a residential loan application, assist a consumer in obtaining a loan, or negotiate terms for a loan. A residential Mortgage Originator is not a person who provides financing to an individual for the purchase of 3 or less[185] properties in a year, or a licensed real estate broker/associate.[186] All Mortgage Originators are to include on all loan documents any unique identifier of the mortgage originator provided by the Registry described in the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008[187]

For any residential mortgage loan, no mortgage originator may receive compensation that varies based on the term of the loan, other than the principal amount. In general, the mortgage originator can only receive payment from the consumer, except as provided in rules that may be established by the Board. Additionally, the mortgage originator must verify the consumer's ability to pay. A violation of the "ability to repay" standard, or a mortgage that has excessive fees or abusive terms, may be raised as a foreclosure defense by a borrower against a lender without regard to any statute of limitations. The Act bans the payment of yield spread premiums or other originator compensation that is based on the interest rate or other terms of the loans.[188]

Subtitle B—Minimum Standards for Mortgages

In effect, this section of the Act establishes national underwriting standards for residential loans. It is not the intent of this section to establish rules or regulations that would require a loan to be made that would not be regarded as acceptable or prudential by the appropriate regulator of the financial institution. However, the loan originator shall make a reasonable and good faith effort based on verified and documented information that "at the time the loan is consummated, the consumer has a reasonable ability to repay the loan, according to the terms, and all applicable taxes, insurance (including mortgage guarantee insurance), and other assessments". Also included in these calculations should be any payments for a second mortgage or other subordinate loans. Income verification is mandated for residential mortgages.[189] Certain loan provisions, including prepayment penalties on some loans, and mandatory arbitration on all residential loans, are prohibited.[190]

This section also defined a "Qualified Mortgage" as any residential mortgage loan that the regular periodic payments for the loan does not increase the principal balance or allow the consumer to defer repayment of principal (with some exceptions), and has points and fees being less than 3% of the loan amount. The Qualified Mortgage terms are important to the extent that the loan terms plus an "Ability to Pay" presumption create a safe harbor situation concerning certain technical provisions related to foreclosure.[191]

Subtitle C—High-Cost Mortgages

A "High-Cost Mortgage" as well as a reverse mortgage are sometimes referred to as "certain home mortgage transactions" in the Fed's Regulation Z (the regulation used to implement various sections of the Truth in Lending Act) High-Cost Mortgage is redefined as a "consumer credit transaction that is secured by the consumer's principal dwelling" (excluding reverse mortgages that are covered in separate sections), which include:[192]

- Credit Transactions secured by consumer's principal dwelling and interest rate is 6.5% more than the prime rate for comparable transactions

- subordinated (ex. second mortgage) if secured by consumer's principal dwelling and interest rate is 8.5% more than the prime rate for comparable transactions

- Points and Fees, excluding Mortgage Insurance, if the transaction is:

- less than $20,000, total points and fees greater than 8% or $1000

- greater than $20,000, total points and fees greater than 6%

- under certain conditions, if the fees and points may be collected more than 36 months after loan is executed

New provisions for calculating adjustable rates as well as definitions for points and fees are also included.

When receiving a High-Cost mortgage, the consumer must obtain pre-loan counseling from a certified counselor.[193] The Act also stipulates there are additional "Requirements to Existing Residential Mortgages". The changes to existing contracts are:

Subtitle D—Office of Housing Counseling

Subtitle D, known as the Expand and Preserve Home Ownership Through Counseling Act,[197] creates a new Office of Housing Counseling, within the department of Housing and Urban Development. The director reports to the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. The Director shall have primary responsibility within the Department for consumer oriented homeownership and rental housing counseling. To advise the Director, the Secretary shall appoint an advisory committee of not more than 12 individuals, equally representing mortgage and real estate industries, and including consumers and housing counseling agencies. Council members are appointed to 3-year terms. This department will coordinate media efforts to educate the general public in home ownership and home finance topics.[198]

The secretary of housing and urban development is authorized to provide grants to HUD-approved housing counseling agencies and state Housing Finance Agencies to provide education assistance to various groups in home ownership.[199] The Secretary is also instructed, in consultation with other federal agencies responsible for financial and banking regulation, to establish a database to track foreclosures and defaults on mortgage loans for 1 through 4 unit residential properties.[200]

Subtitle E—Mortgage Servicing

Subtitle E concerns jumbo rules concerning escrow and settlement procedures for people who are in trouble repaying their mortgages, and also makes amendments to the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act of 1974. In general, in connection with a residential mortgage there should be an established escrow or impound account for the payment of taxes, hazard insurance, and (if applicable) flood insurance, mortgage insurance, ground rents, and any other required periodic payments. Lender shall disclose to borrower at least three business days before closing the specifics of the amount required to be in the escrow account and the subsequent uses of the funds.[201] If an escrow, impound, or trust account is not established, or the consumer chooses to close the account, the servicer shall provide a timely and clearly written disclosure to the consumer that advises the consumer of the responsibilities of the consumer and implications for the consumer in the absence of any such account.[202] The amendments to the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act of 1974 (or RESPA) change how a Mortgage servicer (those who administer loans held by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, etc.) should interact with consumers.[203]

Subtitle F—Appraisal Activities

A creditor may not extend credit for a higher-risk mortgage to a consumer without first obtaining a written appraisal of the property with the following components:[204]

- Physical Property Visit – including a visit of the interior of the property

- Second Appraisal Circumstances – creditor must obtain a second appraisal, with no cost to the applicant, if the original appraisal is over 180 days old or if the current acquisition price is lower than the previous sale price

A "certified or licensed appraiser" is defined as someone who:

- is certified or licensed by the state in which the property is located

- performs each appraisal in conformity with Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice and title XI of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989

The Fed, Comptroller of the Currency, FDIC, National Credit Union Administration Board, Federal Housing Finance Agency and Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (created in this law) shall jointly prescribe regulations.

The use of Automated Valuation Models to be used to estimate collateral value for mortgage lending purposes.[205]

Automated valuation models shall adhere to quality control standards designed to,

- ensure a high level of confidence in the estimates produced by automated valuation models;

- protect against the manipulation of data;

- seek to avoid conflicts of interest;

- require random sample testing and reviews; and

- account for any other such factor that those responsible for formulating regulations deem appropriate

The Fed, the comptroller of the currency, the FDIC, the National Credit Union Administration Board, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection, in consultation with the staff of the appraisal subcommittee and the Appraisal Standards Board of The Appraisal Foundation, shall promulgate regulations to implement the quality control standards required under this section that devises Automated Valuation Models.

Residential and 1- to 4-unit single family residential real estate are enforced by: Federal Trade Commission, the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection, and a state attorney general. Commercial enforcement is by the Financial regulatory agency that supervised the financial institution originating the loan.

Broker Price Opinions may not be used as the primary basis to determine the value of a consumer's principal dwelling; but valuation generated by an automated valuation model is not considered a Broker Price Opinion.

The standard settlement form (commonly known as the HUD 1) may include, in the case of an appraisal coordinated by an appraisal management company, a clear disclosure of:[206]

- the fee paid directly to the appraiser by such company

- the administration fee charged by such company

Within one year, the Government Accountability Office shall conduct a study on the effectiveness and impact of various appraisal methods, valuation models and distribution channels, and on the home valuation code of conduct and the appraisal subcommittee.[207]

Subtitle G—Mortgage Resolution and Modification

The Secretary of Housing and Urban Development is charged with developing a program to ensure protection of current and future tenants and at-risk multifamily (5 or more units) properties. The Secretary may coordinate the program development with the Secretary of the Treasury, the FDIC, the Fed, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and any other federal government agency deemed appropriate. The criteria may include:[208]

- creating sustainable financing of such properties, that may take into consideration such factors as:

- the rental income generated by such properties

- the preservation of adequate operating reserves

- maintaining the current level of federal, state, and city subsidies

- funds for rehabilitation

- facilitating the transfer of such properties, when appropriate and with the agreement of owners

Previously the Treasury Department has created the Home Affordable Modification Program, set up to help eligible home owners with loan modifications on their home mortgage debt. This section requires every mortgage servicer participating in the program and denies a re-modification request to provide the borrower with any data used in a net present value (NPV) analysis. The Secretary of the Treasury is also directed to establish a Web-based site that explains NPV calculations.[209]

The Secretary of the Treasury is instructed to develop a Web-based site to explain the Home Affordable Modification Program and associated programs, that also provides an evaluation of the impact of the program on home loan modifications.[210]

Subtitle H—Miscellaneous Provisions

- It is the sense of the Congress that significant structural reforms of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are required[211]

- GAO is commissioned to study current inter-agency efforts to reduce mortgage foreclosure and eliminate rescue scams and loan modification fraud.[212]

- HUD is commissioned to study the impact of defective drywall imported from China from 2004 through 2007 and their effect on foreclosures.[213]

- Additional funding for Mortgage Relief and Neighborhood Stabilization programs ($1 billion each)[214]

- HUD to establish legal assistance for foreclosure-related issues with $35 million authorized for fiscal years 2011 through 2012.[215]

Title XV—Miscellaneous Provisions

The following sections have been added to the Act:

Restriction on U.S. approval of loans issued by International Monetary Fund

The US Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund is instructed to evaluate any loan to a country if

- The amount of the public debt of the country exceeds the annual gross domestic product of the country

- the country is not eligible for assistance from the International Development Association and to oppose any loans unlikely to be repaid in full.[216]

Disclosures on conflict materials in or near the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- The SEC is mandated to create rules that address potential conflict materials (e.g. coltan, tantalum, tin, tungsten, gold or their derivatives) and to assess whether materials originating in or near the Democratic Republic of the Congo are benefiting armed groups in the area.[217]

- The Secretary of State and Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development are required to develop a strategy to address the linkages between human rights abuses, armed groups, mining of conflict minerals, and commercial products, and promoted peace and security in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[217]

- An industry group has complained that the legislation goes beyond voluntary industry initiative such as the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme.[218][219]

- The United Nations Security Council committee charged with overseeing conflict minerals issues reported that this legislation was a "catalyst" for efforts to save lives by cutting off a key source of funding for armed groups.[220]

Reporting on mine safety

Requires the SEC to report on mine safety by gathering information on violations of health or safety standards, citations and orders issued to mine operators, number of flagrant violations, value of fines, number of mining-related fatalities, etc., to determine whether there is a pattern of violations.[221]

Reporting on payments by oil, gas and minerals industries for acquisition of licenses

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 is amended by section 1504 Dodd-Frank Act to require disclosure of payments relating to the acquisition of licenses for exploration, production, etc., where "payment" includes fees, production entitlements, bonuses, and other material benefits.[222] These documents should be made available online to the public.[222] Rule 240.13q-1 would have required most corporations to begin disclosing payments in 2019, but this rule has been removed in order to reduce the regulatory burden facing corporations. [223]

Study on effectiveness of inspectors general