Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (DPM) is a senior member of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom. The office of the Deputy Prime Minister is not a permanent position,[1] existing only at the discretion of the Prime Minister, who may appoint to other offices, such as First Secretary of State, to give seniority to a particular cabinet minister. Due to the two offices tending not to coincide, and both representing the Prime Minister's deputy, some journalists may refer informally to the First Secretary of State as the Deputy PM. More recently, under the Second May ministry, the functions of this office were exercised by the Minister for the Cabinet Office.

| Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Royal Arms of Her Majesty's Government | |

Incumbent (Office not in use) since 2015 | |

| Government of the United Kingdom | |

| Style | Deputy Prime Minister (informal) The Right Honourable (UK and Commonwealth) |

| Member of | Cabinet Privy Council National Security Council |

| Reports to | Prime Minister |

| Residence | None, may use Grace and favour residences |

| Seat | Westminster, London |

| Appointer | The Monarch on advice of the Prime Minister |

| Term length | No fixed term |

| Formation | 19 February 1942 |

| First holder | Clement Attlee |

| Website | www.gov.uk |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

|

Elizabeth II

Rishi Sunak (C)

|

|

Legislature

Elizabeth II

The Lord Fowler

Sir Lindsay Hoyle

Sir Keir Starmer (L)

|

|

Judiciary Elizabeth II (Queen-on-the-Bench)

The Lord Reed

The Lord Hodge

|

|

|

|

Elections

UK General Elections

European Parliament Elections (1979–2019)

Scottish Parliament Elections

Northern Ireland Assembly Elections

Welsh Parliament (Senedd Cymru) Elections

Referendums

|

|

Devolution

|

Northern Ireland

|

|

|

Foreign relations

|

|

Unlike analogous offices in some other nations, such as the Vice President of the United States or the Deputy Prime Minister of Ireland (or Tánaiste), the British deputy prime minister possesses no special constitutional powers as such, though he or she will always have particular responsibilities in government. The DPM does not assume the duties and powers of the Prime Minister in the latter's absence, illness, or death, such as the powers to seek a dissolution of Parliament, appoint peers or brief the sovereign.

The designation of someone to the role of Deputy Prime Minister may provide additional practical status within the cabinet, enabling exercise of de facto, if not de jure, power. However, the Deputy Prime Minister does not automatically succeed the Prime Minister when the latter is incapacitated, or resigns from the leadership of his or her party.

In a coalition government, such as the 2010–2015 coalition government between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, the appointment of the leader of the smaller party (in the 2010 case, Nick Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrats) as Deputy Prime Minister is done to give that person more authority within the Cabinet to enforce the coalition's agreed-upon agenda. The Deputy Prime Minister usually deputises for the Prime Minister at official functions, such as Prime Minister's Questions.

Absence of the office in the constitution

Many theories exist as to the absence of a formal post of Deputy Prime Minister in Britain's uncodified constitution. Theoretically the sovereign possesses the unrestricted right to choose someone to form a government[note 1] following the death, resignation or dismissal of a Prime Minister.[note 2][2] One argument made to justify the non-existence of a permanent deputy premiership is that such an office-holder would be seen as possessing a presumption of succession to the premiership, thereby effectively limiting the sovereign's right to choose a prime minister.[note 3]

However, only two Deputy Prime Ministers have gone on to become Prime Minister. Clement Attlee led his party to victory in the 1945 general election and succeeded Winston Churchill's first premiership after their coalition broke up, but only after a two-month interval when Attlee was not a member of the government. Anthony Eden succeeded Churchill after his second premiership in 1955, not because he had been Deputy Prime Minister, but because he had long been seen as Churchill's heir apparent and natural successor.

The intermittent existence of a Deputy Prime Minister has been on occasion so informal that there have been a number of occasions on which dispute has arisen as to whether or not the title has actually been conferred.

The position of Deputy Prime Minister is not recognised in United Kingdom law, so any post-holder must be given an additional title in order to have legal status and to be paid a salary additional to the parliamentary one. Nick Clegg, Deputy Prime Minister from 2010 to 2015, was appointed Lord President of the Council, a minister who presides over meetings of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council and has few other formal responsibilities, for this reason. On some occasions the post of First Secretary of State has been used; when John Prescott lost his departmental responsibilities in a reshuffle in 2001, he was given the office to enable him to retain a ministerial post, and Michael Heseltine was similarly appointed.

Choice

The Deputy Prime Ministership, where it exists, may bring with it practical influence depending on the status of the holder, rather than the status of the position.

Labour Party leader Clement Attlee held the post in the wartime coalition government led by Winston Churchill, and had general responsibility for domestic affairs, allowing Churchill to concentrate on the war. Rab Butler held the post in 1962–63 under Harold Macmillan, but was passed over for the premiership in favour of Alec Douglas-Home.

During Edward Heath's government (1970–1974), the title of Deputy Prime Minister was not formally used. However, in his Memoirs, Home Secretary Reginald Maudling described himself as Deputy Prime Minister under Heath from 1970 to his resignation in 1972 over the Poulson affair. William Armstrong, head of the Civil Service, was also called Heath's Deputy Prime Minister.[3] The Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, Ted Short, was Leader of the House of Commons from 1974 to 1976 under Harold Wilson and often thought of as Deputy Prime Minister; he was referred to as such in the citation for being made an Honorary Freeman of the City of Newcastle upon Tyne.

William Whitelaw was Margaret Thatcher's de facto deputy from 1979–1988,[4] an unofficial position he combined with that of Home Secretary in 1979–1983 and Leader of the House of Lords after 1983. Sir Geoffrey Howe was bestowed the title of Deputy Prime Minister by Thatcher in 1989,[4] on being removed from the post of Foreign Secretary. He resigned as her deputy in 1990, making a resignation speech that is widely thought to have hastened Thatcher's downfall. Thatcher's successor John Major did not appoint a Deputy Prime Minister until 1995, when Michael Heseltine was given the title.

John Prescott, who was elected Deputy Leader of the Labour Party in opposition, was appointed Deputy Prime Minister by Tony Blair in 1997, in addition to being Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions. In 2001 this "superdepartment" was split up, with Prescott being given his own Office of the Deputy Prime Minister with fewer specific responsibilities. In May 2006, the department was removed from the control of the Deputy Prime Minister and renamed as the Department for Communities and Local Government with Ruth Kelly as the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government.

Following the 2010 general election, which returned a hung parliament, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats agreed to form a coalition government. As leader of the smaller of the two parties in the coalition, Nick Clegg was appointed Deputy Prime Minister on the advice of the new Prime Minister, Conservative leader David Cameron.

Clegg was the last person to officially hold the post as, following the subsequent 2015 election, in which the Conservatives won an overall majority in the House of Commons, Cameron decided not to appoint a replacement. He chose instead to appoint the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne as First Secretary of State— effectively his deputy. After the 2016 referendum on European Union membership, and David Cameron's subsequent resignation, his successor as Prime Minister, Theresa May, also chose not to appoint an individual to either position. Following the 2017 snap general election, May again did not appoint a Deputy Prime Minister but did appoint Damian Green as First Secretary of State.[5]

After Green's resignation in 2017, the de facto Deputy Prime Minister function and responsibility was carried out by David Lidington in the office as Minister for the Cabinet Office, before passing to new First Secretary of State Dominic Raab in 2019.

Office and residence

The Deputy Prime Minister's Office (DPMO) is a non-statutory office, only being formed when a deputy prime minister is appointed which consists of the staff members and advisers who assist the deputy prime minister in his or her role. The most recent Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg maintained an office at the Cabinet Office headquarters, 70 Whitehall, which is linked to 10 Downing Street.[6] Clegg's predecessor, John Prescott, maintained his main office at 26 Whitehall.[7] The office is not an official single department and as such is part of and organised as part of the Cabinet Office.

Given that there is no constitutional office of Deputy Prime Minister, with the position being recreated on a case by case basis, the person who holds the post has no official residence. As a cabinet minister, however, they may have the use of a grace and favour London residence and country house. While in office, Nick Clegg resided at his private residence in Putney, London, and he shared Chevening House with former Foreign Secretary William Hague as a weekend residence.[8] Clegg's predecessor, John Prescott, had the use of a flat in Admiralty House and used Dorneywood as his country residence.

List of Deputy Prime Ministers

| Name | Picture | Term of office | Party | Ministerial office(s) | PM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clement Attlee |  |

19 February 1942 | 23 May 1945 | Labour (Leader)[note 4] |

|

Churchill (Coalition) | ||

| Herbert Morrison |  |

26 July 1945 | 26 October 1951 | Labour (Deputy Leader) |

|

Attlee (I & II) | ||

| Anthony Eden | .jpg) |

26 October 1951 | 6 April 1955 | Conservative |

|

Churchill (III) | ||

| Office not in use | 1955–1962 | N/A | Eden | |||||

| Macmillan | ||||||||

| Rab Butler |  |

13 July 1962 | 18 October 1963 | Conservative |

| |||

| Office not in use | 1963–1989[note 5] | N/A | Home | |||||

| Wilson | ||||||||

| Heath | ||||||||

| Wilson | ||||||||

| Callaghan | ||||||||

| Thatcher | ||||||||

| Geoffrey Howe | .jpg) |

24 July 1989 | 1 November 1990 | Conservative |

| |||

| Office not in use | 1990–1995 | N/A | Major | |||||

| Michael Heseltine | .jpg) |

20 July 1995 | 2 May 1997 | Conservative |

| |||

| John Prescott |  |

2 May 1997 | 27 June 2007 | Labour (Deputy Leader) |

|

Blair | ||

| Office not in use | 2007–2010 | N/A | Brown | |||||

| Nick Clegg | .jpg) |

11 May 2010 | 8 May 2015 | Liberal Democrats (Leader)[note 4] |

|

Cameron (Coalition) | ||

| Office not in use | 2015–present | N/A | Cameron (Majority) | |||||

| May | ||||||||

| Johnson | ||||||||

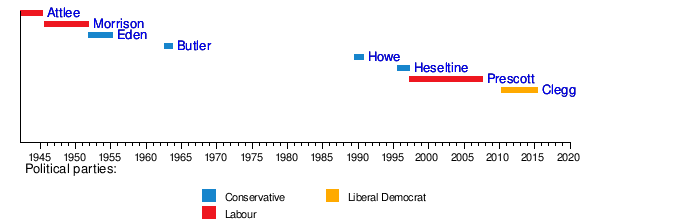

Timeline

See also

- Deputy Leader of the Conservative Party (UK)

- Deputy Leader of the Labour Party (UK)

- First Secretary of State

Footnotes

- In the British constitutional tradition, the sovereign invites someone to form a government "capable of surviving in the House of Commons". This is not the same as having a majority. In theory a minority government could survive if the opposition parties were divided on issues and so failed to all vote together against the government. In times of national emergency, sovereigns set a different, higher standard, namely that a government be formed "capable of commanding a majority in the House of Commons". In the event of no party possessing a majority, this forces the party invited to form a government to enter into a coalition with another party. This latter request was made on only a handful of cases, most notably in 1916 when King George V invited Bonar Law to form a government, who declined so the King invited David Lloyd George to form a government. Lloyd George was forced by the nature of his commission to form a coalition government.

- No Prime Minister has been dismissed by a sovereign since 1834. Except in exceptional circumstances it is thought unlikely that a prime minister would ever be dismissed.[2]

- In practice the monarch's choice has been limited by the evolution of a clear party structure, with each party possessing a structure by which leaders are elected. Only where no party has a majority, or where a division exists between the person chosen by the party's electoral college and its MPs on who should be prime minister, can a modern sovereign expect to freely choose whom to appoint.

- Leader of the junior party in a coalition government.

- William Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw served as deputy leader of the Conservative Party under Thatcher and Major from 1975 to 1991. Although he served in cabinet from 1979 to 1988 he never officially acquired the title of Deputy Prime Minister.[4]

References

- "Deputy prime minister: Glossary item: Glossary – TheyWorkForYou". TheyWorkForYou. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Stanley de Smith and Rodney Brazier, Constitutional and Administrative Law (Penguin, 1989) p.116.

- Ziegler, Philip. "How the last Tory-Liberal deal fell apart" The Sunday Times, 9 May 2010.

- Hennessy, Peter (2001). "A Tigress Surrounded by Hamsters: Margaret Thatcher, 1979–90". The Prime Minister: The Office and Its Holders since 1945. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-028393-8.

- Stewart, Heather. "Theresa May appoints close ally Damian Green as first secretary of state". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- "Nick Clegg could be given use of stately home where John Prescott played croquet". Telegraph. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Deputy Prime Minister | Contact us". Archive.cabinetoffice.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Hague and Clegg given timeshare of official residence". BBC News. 18 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Clegg To Be Cameron's Deputy In New Cabinet Sky News Archived 15 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg to be deputy PM". Reuters. 12 May 2010.