Deliverance

Deliverance is a 1972 American thriller film produced and directed by John Boorman, and starring Jon Voight, Burt Reynolds, Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox, with the latter two making their feature film debuts. The screenplay was adapted by James Dickey from his 1970 novel of the same name. The film was a critical success, earning three Oscar nominations and five Golden Globe Award nominations.

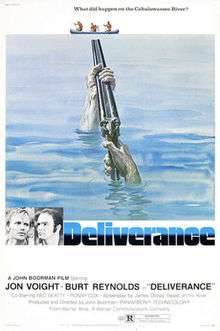

| Deliverance | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | John Boorman |

| Produced by | John Boorman |

| Screenplay by | James Dickey |

| Based on | Deliverance by James Dickey |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Eric Weissberg |

| Cinematography | Vilmos Zsigmond |

| Edited by | Tom Priestley |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million |

| Box office | $46.1 million[1] |

Widely acclaimed as a landmark picture, the film is noted for a music scene near the beginning, with one of the city men playing "Dueling Banjos" on guitar with a banjo-strumming country boy, and for its visceral and notorious rape scene. In 2008, Deliverance was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Plot

Four Atlanta businessmen, Lewis Medlock, Ed Gentry, Bobby Trippe and Drew Ballinger, decide to canoe down a river in the remote northern Georgia wilderness, expecting to have fun and witness the area's unspoiled nature before the fictional Cahulawassee River valley is flooded by construction of a dam. Lewis, an experienced outdoorsman, is the leader. Ed is a good friend of Lewis and also a veteran of several trips but lacks Lewis' machismo. Bobby and Drew are novices. While traveling to their launch site, the men (Bobby in particular) are condescending towards the locals, who are unimpressed by the "city boys". At a local gas station Drew engages a young boy (implied to be inbred) in a musical duel, with the boy on banjo and Drew on his guitar. Although the duel appears mutual and Drew enjoys it, the boy does not acknowledge him when prompted for a congratulatory handshake.

The men spend the first day canoeing without incident, successfully negotiating the rapids that dot the river. About to go to sleep, Lewis takes off into the dark only to return a few moments later saying that he thought he had heard something or someone. In the morning while the others are still asleep Ed takes Lewis's recurve bow to hunt but misses a clear shot he has of a deer.

Traveling in pairs, the foursome, in their two canoes, are briefly separated. Bobby and Ed, in the one craft, land briefly and encounter a pair of local hillbillies emerging from the woods, one of whom is carrying a shotgun. After a verbal altercation, Bobby is forced at gunpoint to strip, his ear twisted to bring him to his hands and knees, and then ordered to "squeal like a pig" before being raped by one of the locals. Ed is bound to a tree and held at gunpoint by the other man.

While the second local prepares to assault Ed sexually after the first has finished with Bobby, Lewis and Drew arrive, unnoticed by the locals. As soon as Lewis kills one of the rapists with an arrow from his bow, the other man dashes away into the woods.

A brief but hotheaded debate between Lewis and Drew concludes with Bobby and Ed's voting for Lewis's recommendation to bury the dead man's body and continue on as if nothing had happened. Drew had wanted to inform the authorities, but Lewis has argued that the four of them would receive no fair trial for the killing, since the local jury would be composed of the dead man's friends and relatives. His view is that the body will soon be buried by the water backed up by the dam and will never be found. Bobby, for his part, doesn't want what happened to him to be known.

The four continue downriver but soon disaster strikes as the canoes reach a dangerous stretch of rapids. As Drew and Ed reach the rapids in the lead canoe, Drew shakes his head and falls into the water. It is unclear why.

When the survivors' canoes collide on the rocks, spilling Lewis, Bobby and Ed into the river, Lewis breaks his femur and the others are washed ashore alongside him. Encouraged by the badly injured Lewis, who believes the escaped local is stalking them and shot Drew, Ed climbs a nearby rock face in order to dispatch the stalker with his bow. Bobby stays behind to look after Lewis. After reaching the top and hiding out until the next morning, Ed sees a man he takes to be the stalker appear on the cliff top with a rifle and look down into the gorge where Lewis and Bobby are located. Ed clumsily shoots and manages to kill the man, accidentally stabbing himself with one of his own spare arrows in the process.

Returning to the others with the body of the man he has killed, Bobby is uncertain that the dead man is the man who had fled from them earlier, but Ed convinces him that he is. Bobby and Ed weigh down the body in the river, to ensure it will never be found, and repeat the same with Drew's body, which they encounter downriver. Lewis is too distracted with pain to do anything more than encourage this compounding of their hiding of what they've experienced.

Upon finally reaching the small town of Aintry, Bobby and Ed take Lewis to the hospital. To the authorities, the men present a cover story that Drew's death and disappearance were accidental, with no mention of the four men's encounter with the two locals. The story is clearly doubted by the local Sheriff Bullard and by Bullard's deputy, whose brother-in-law, the sheriff says, hasn't returned from a hunting trip back up there in the mountains. Having no legal basis to hold the men, Bullard simply tells them never to come back. Affecting levity, Bobby replies that they sure won't.

With Lewis still hospitalized and in danger of losing his leg, Bobby and Ed take leave of each other to head home separately. Declining Bobby's offer to handle it, Ed says he will carry out the duty of informing Drew's wife of Drew's death.

At his own home, Ed is comforted by his wife and returns to his role of husband and father. One night, Ed dreams of a dead man’s hand rising from a lake, which wakes him up and causes him to bolt upright in bed. His wife gently settles him back down beside her and tells him to go to sleep.

Cast

- Jon Voight as Ed

- Burt Reynolds as Lewis

- Ned Beatty as Bobby

- Ronny Cox as Drew

- Bill McKinney as Mountain Man

- Herbert "Cowboy" Coward as Toothless Man

- James Dickey as Sheriff Bullard

- Billy Redden as Lonnie, the banjo boy

- Macon McCalman as Deputy Queen, whose brother-in-law is missing

In addition, Ned Beatty's then wife, Belinda Beatty, and director John Boorman's son, Charley Boorman, briefly appear as the wife and young child of Jon Voight's character.

Production

Deliverance was shot primarily in Rabun County in northeastern Georgia. The canoe scenes were filmed in the Tallulah Gorge southeast of Clayton and on the Chattooga River. This river divides the northeastern corner of Georgia from the northwestern corner of South Carolina. Additional scenes were shot in Salem, South Carolina.

A scene was also shot at the Mount Carmel Baptist Church cemetery. This site has since been flooded and lies 130 feet under the surface of Lake Jocassee, on the border between Oconee and Pickens counties in South Carolina.[2][3] The dam shown under construction is Jocassee Dam.

During the filming of the canoe scene, author James Dickey showed up inebriated and entered into a bitter argument with producer-director John Boorman, who had rewritten Dickey's script. They allegedly had a brief fistfight in which Boorman, a much smaller man than Dickey, suffered a broken nose and four shattered teeth.[4] Dickey was thrown off the set, but no charges were filed against him. The two reconciled and became good friends, and Boorman gave Dickey a cameo role as the sheriff at the end of the film.

The inspiration for the Cahulawassee River was the Coosawattee River, which was dammed in the 1970s and contained several dangerous whitewater rapids before being flooded by Carters Lake.[5]

Casting

Casting was by Lynn Stalmaster. Dickey had initially wanted Sam Peckinpah to direct the film.[4] Dickey also wanted Gene Hackman to portray Ed Gentry whereas Boorman wanted Lee Marvin to play the role.[4] Boorman also wanted Marlon Brando to play Lewis Medlock.[4] Jack Nicholson was considered for the role of Ed,[4] while both Donald Sutherland and Charlton Heston turned down the role of Lewis.[4] Other actors who were attached to the project included Robert Redford, Henry Fonda, George C. Scott and Warren Beatty.[4]

Stunts

The film is infamous for cutting costs by not insuring the production and having the actors perform their own stunts (most notably, Jon Voight climbed the cliff himself). In one scene, the stunt coordinator decided that a scene showing a canoe with a dummy of Burt Reynolds in it looked phony; he said it looked "like a canoe with a dummy in it". Reynolds requested to have the scene re-shot with himself in the canoe rather than the dummy. After shooting the scene, Reynolds, coughing up river water and nursing a broken coccyx, asked how the scene looked. The director responded, "like a canoe with a dummy in it".

Regarding the courage of the four main actors in the movie performing their own stunts without insurance protection, Dickey was quoted as saying all of them "had more guts than a burglar." In a nod to their stunt-performing audacity, early in the movie Lewis says, "Insurance? I've never been insured in my life. I don't believe in insurance. There's no risk".

"Squeal like a pig"

Several people have been credited with the phrase "squeal like a pig", the now-famous line spoken during the graphic rape scene. Ned Beatty said he thought of it while he and actor McKinney (who played Beatty's rapist) were improvising the scene.[6] James Dickey's son, Christopher Dickey, wrote in his memoir about the film production, Summer of Deliverance, that because Boorman had rewritten so much dialogue for the scene one of the crewmen suggested that Beatty's character should just "squeal like a pig".[7] Boorman himself, however, in a DVD commentary he made for the film said the line was used because the studio wanted the male rape scene to be filmed in two ways: one for cinematic release and one that would be acceptable for television. As Boorman did not want to do that, he decided that the phrase "squeal like a pig", suggested by Rabun County liaison Frank Rickman, was a good replacement for the original dialogue in the script.[8]

Soundtrack and copyright dispute

The film's soundtrack brought new attention to the musical work "Dueling Banjos", which had been recorded numerous times since 1955. Only Eric Weissberg and Steve Mandel were originally credited for the piece. The onscreen credits state that the song is an arrangement of the song "Feudin' Banjos", showing Combine Music Corp as the copyright owner. Songwriter and producer Arthur "Guitar Boogie" Smith, who had written "Feudin' Banjos" in 1955, and recorded it with five-string banjo player Don Reno, filed a lawsuit for songwriting credit and a percentage of royalties. He was awarded both in a landmark copyright infringement case.[9] Smith asked Warner Bros. to include his name on the official soundtrack listing, but reportedly asked to be omitted from the film credits because he found the film offensive.[10]

No credit was given for the film score. The film has a number of sparse, brooding passages of music scattered throughout, including several played on a synthesizer. Some prints of the movie omit much of this extra music.

Boorman was given a gold record for the "Dueling Banjos" hit single; this was later stolen from his house by the Dublin gangster Martin Cahill. Boorman recreated this scene in The General (1998), his biographical film about Cahill.[11]

Reception

Deliverance was a box office success in the United States, becoming the fifth-highest grossing film of 1972, with a domestic take of over $46 million.[1] The film's financial success continued the following year, when it went on to earn $18 million in North American "distributor rentals" (receipts).[12]

Critical reception

Deliverance was well received by critics and is widely regarded as one of the best films of 1972.[13][14][15][16] The film is in the top tier of films on review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, with a 90% rating based on reviews from 61 critics.[17]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film four stars out of four and wrote, "It is a gripping horror story that at times may force you to look away from the screen, but it is so beautifully filmed that your eyes will eagerly return."[18] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "an engrossing adventure, a demonstrable labor of love whose pains have largely paid off in making us empathize with stirring deeds in a setting of cruel beauty. Reynolds suggests that given the right material he is more than just another pretty hand and Voight, in the most substantial role he has had since 'Midnight Cowboy' proves again what a versatile actor he is. Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox are excellent in the briefer roles as the other voyagers."[19] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote that the film was "certainly a distinctive and gripping piece of work, with a deliberately brooding, ominous tone and visual style that put you in a grave, fearful frame of mind, almost in spite of yourself."[20]

Not all reviews were positive. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times said:

Dickey, who wrote the original novel and the screenplay, lards this plot with a lot of significance – universal, local, whatever happens to be on the market. He is clearly under the impression that he is telling us something about the nature of man, and particularly civilized man's ability to survive primitive challenges[…] But I don't think it works that way.[…] What the movie totally fails at, however, is its attempt to make some kind of significant statement about its action.[…] [W]hat James Dickey has given us here is a fantasy about violence, not a realistic consideration of it.[…] It's possible to consider civilized men in a confrontation with the wilderness without throwing in rapes, cowboy-and-Indian stunts and pure exploitative sensationalism.[21]

Arthur D. Murphy of Variety wrote that the setting was "majestic" but it was "in the fleshing out that the script fumbles, and with it the direction and acting."[22] Vincent Canby of The New York Times was also generally negative, calling the film "a disappointment" because "so many of Dickey's lumpy narrative ideas remain in his screenplay that John Boorman's screen version becomes a lot less interesting than it has any right to be."[23]

The instrumental piece, "Dueling Banjos", won the 1974 Grammy Award for Best Country Instrumental Performance. The film was selected by The New York Times as one of The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made, while the viewers of Channel 4 in the United Kingdom voted it #45 on a list of The 100 Greatest Films.

Reynolds later called it "the best film I've ever been in".[24] However, he stated that the rape scene went "too far".[25]

Awards and nominations

- Nominated

- Academy Award for Best Picture

- Academy Award for Best Director — John Boorman

- Academy Award for Best Film Editing — Tom Priestley

- New York Film Critics Circle for Best Film and Best Director

- Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama

- Golden Globe Award for Best Director – Motion Picture — John Boorman

- Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama — Jon Voight

- Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song — Arthur "Guitar Boogie" Smith, Eric Weissberg, and Steve Mandel

- Golden Globe Award for Best Screenplay — James Dickey

American Film Institute lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills—#15

Legacy

Following the film's release, Governor Jimmy Carter established a state film commission to encourage television and movie production in Georgia. The state has "become one of the top five production destinations in the U.S".[26] Tourism increased to Rabun County by the tens of thousands after the film's release. By 2012, tourism was the largest source of revenue in the county.[26] Jon Voight's stunt double for this film, Claude Terry, later purchased equipment used in the movie from Warner Brothers. He founded what is now the oldest whitewater rafting adventure company on the Chattooga River, Southeastern Expeditions.[27] By 2012, rafting had developed as a $20 million industry in the region.[26]

See also

- List of American films of 1972

- Survival film, about the film genre, with a list of related films

References

- "Deliverance, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- Simon, Anna (2009-02-20). "Cable network to detail history of Lake Jocassee". The Greenville News. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- Heldenfels, Rich (2009-11-05). "Body double plays banjo". Akron Beacon Journal. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- Lyttleton, Oliver (30 July 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About 'Deliverance,' Released 40 Years Ago Today". IndieWire. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Roper, Daniel M. "The Story of the Coosawattee River Gorge". North Georgia Journal (Summer 1995). Archived from the original on 2010-12-22.

- Burger, Mark. (2006, March 19). "BEATTY GIVEN MASTER OF CINEMA AWARD; CHARACTER ACTOR IS A VETERAN OF MORE THAN 200 FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTIONS", Winston-Salem Journal, Page B1

"Regarding his debut film, Deliverance (1972), in which his character undergoes an unforgettably vivid sexual assault, Beatty said: 'The whole "squeal like a pig" thing ... came from guess who.' As the audience laughed, he theatrically put his head in his hands and silently pointed to himself, before elaborating how director Boorman encouraged him to improvise the scene with his onscreen tormentor, Bill McKinney." - Dickey, Christopher (2010). Summer of Deliverance: A Memoir of Father and Son. Simon and Schuster. p. 186. ISBN 1439129592.

- "Rabun County Historical Society". www.rabunhistory.org. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "Country guitarist Arthur Smith dies". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- McArdle, Terence (6 April 2014). "Arthur Smith, guitarist who wrote 'Guitar Boogie' and 'Duelin' Banjos,' dies at 93". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Artistic reunion brings Martin Cahill to life". The Irish Echo. May 27 – June 2, 1998. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Big Rental Films of 1973," Variety, 9 January 1974 p 19

- "Greatest Films of 1972". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- "The Best Movies of 1972 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- "Best Films of the 1970s". Cinepad.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- IMDb: Year: 1972

- "Deliverance". Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- Siskel, Gene (October 5, 1972). "Deliverance". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 4.

- Champlin, Charles (August 13, 1972). "Men Against River—of Life?—in 'Deliverance'". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 17.

- Arnold, Gary (October 5, 1972). "' Deliverance': A Gripping Piece of Work". The Washington Post. B1.

- "Deliverance." Chicago Sun-Times.

- Murphy, Arthur D. (July 19, 1972). "Film Reviews: Deliverance". Variety. 14.

- Canby, Vincent (July 31, 1972). "The Screen: James Dickey's 'Deliverance' Arrives". The New York Times. 21.

- Workaholic Burt Reynolds sets up his next task: Light comedy Siskel, Gene. Chicago Tribune (1963–Current file) [Chicago, Ill] 28 Nov 1976: e2.

- "Reynolds: 'Deliverance Rape Scene Went Too Far'". Contactmusic.com. 21 January 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Welles, Cory (August 22, 2012). "40 years later, 'Deliverance' causes mixed feelings in Georgia". Marketplace. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- "About us". Southeastern Expeditions. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

Further reading

- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp 94–95.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Deliverance |