Catenaccio

Catenaccio (Italian pronunciation: [kateˈnattʃo]) or The Chain is a tactical system in football with a strong emphasis on defence. In Italian, catenaccio means "door-bolt", which implies a highly organised and effective backline defence focused on nullifying opponents' attacks and preventing goal-scoring opportunities.

History

Predecessors and influences

Italian Catenaccio was influenced by the verrou (also "doorbolt/chain" in French) system invented by Austrian coach Karl Rappan.[1] As coach of Switzerland in the 1930s and 1940s, Rappan played a defensive sweeper called the verrouilleur, positioned just ahead of the goalkeeper.[2] Rappan's verrou system, proposed in 1932, when he was coach of Servette, was implemented with four fixed defenders, playing a strict man-to-man marking system, plus a playmaker in the middle of the field who played the ball together with two midfield wings.

Italian catenaccio

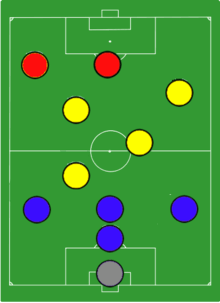

In the 1950s, Nereo Rocco's Padova pioneered catenaccio in Italy where it would be used again by the Internazionale team of the early 1960s.[3][4] Rocco's tactic, often referred to as the real Catenaccio, was shown first in 1947 with Triestina: the most common mode of operation was a 1–3–3–3 formation with a strictly defensive team approach. With catenaccio, Triestina finished the Serie A tournament in a surprising second place. Some variations include 1–4–4–1 and 1–4–3–2 formations. He later had great success with Milan using the catenaccio system during the 60s and 70s, winning several titles, including two Serie A titles, three Coppa Italia titles, two European Cups, two European Cup Winners' Cups, and an Intercontinental Cup.[5][6]

The key innovation of Catenaccio was the introduction of the role of a libero ("free") defender, also called "sweeper", who was positioned behind a line of three defenders. The sweeper's role was to recover loose balls, nullify the opponent's striker and double-mark when necessary. Another important innovation was the counter-attack, mainly based on long passes from the defence.

In Helenio Herrera's version in the 1960s, four man-marking defenders were tightly assigned to the opposing attackers while an extra player, the sweeper, would pick up any loose ball that escaped the coverage of the defenders. The emphasis of this system in Italian football spawned the rise of many top Italian defenders who became known for their hard-tackling and ruthless defending. However, despite the defensive connotations, Herrera claimed shortly before his death that the system was more attacking than people remembered, saying 'the problem is that most of the people who copied me copied me wrongly. They forgot to include the attacking principles that my Catenaccio included. I had Picchi as a sweeper, yes, but I also had Facchetti, the first full back to score as many goals as a forward.' Indeed, although his Grande Inter side were known primarily for their defensive strength, they were equally renowned for their ability to score goals with few touches from fast, sudden counter-attacks, due to Herrera's innovative use of attacking, overlapping full-backs. Under Herrera, Inter enjoyed a highly successful spell, which saw them win three Serie A titles, two European Cups, and two Intercontinental Cups.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

Jock Stein's Celtic defeated the catenaccio system in the 1967 European Cup Final. They beat Inter Milan 2–1 on the 25th of May 1967 creating the blue print for Michels total football, a continuation of Stein's free flowing attacking football.

Total Football, invented by Rinus Michels in the 1970s, exposed weaknesses in Herrera's version of Catenaccio. In Total Football, no player is fixed in his nominal role; anyone can assume in the field the duties of an attacker, a midfielder or a defender, depending on the play. Man-marking alone was insufficient to cope with this fluid system. Coaches began to create a new tactical system that mixed man-marking with zonal defense. In 1972, Michels' Ajax defeated Inter 2–0 in the European Cup final and Dutch newspapers announced the "destruction of Catenaccio" at the hands of Total Football. In 1973, Ajax defeated Cesare Maldini's Milan 6–0 for the European Super Cup in a match in which the defensive Milan system was unable to stop Ajax.

Modern use of catenaccio

Pure Catenaccio is rarely used in modern football tactics. Two major characteristics of this style – the man-to-man marking and the libero ("free") position – are very rarely employed. Highly defensive structures with little attacking intent are often arbitrarily labelled as Catenaccio, but this deviates from the original design of the system.[13]

Although Catenaccio has still come to be associated with the Italian national side and Italian club teams, due to its historic association with Italian football, it is actually used quite infrequently by Serie A and Italian national teams in contemporary football, who instead currently prefer to apply balanced tactics and formations, mostly using the 5–3–2 or 3–5–2 system.[14] For example, under manager Cesare Prandelli, the Italian national football team also initially used the 3–5–2 formation – which had been popularised by Juventus manager Antonio Conte – with a sweeper and wing-backs in their first clashes of UEFA Euro 2012 Group C; the system resulted in two 1–1 draws against Spain and Croatia. He subsequently switched to a stylish attacking possession-based system using their 'standard' 4–4–2 diamond formation for the knockout stages; the switch proved to be effective, as the team went on to reach the final, where they suffered a 4–0 defeat to a similarly offensive-minded Spanish side.[15][16][17][18]

Several of Italy's previous coaches, such as Cesare Maldini and Giovanni Trapattoni, used elements of catenaccio at international level,[19][20] and both failed to go far in the tournaments in which they took part; under Maldini, Italy lost on penalties to hosts France in the 1998 FIFA World Cup quarter-finals, following a 0–0 draw,[21] while Trapattoni lost early in the second round of the 2002 FIFA World Cup to co-hosts South Korea on a golden goal,[22] and subsequently suffered a first-round elimination at UEFA Euro 2004.[23]

While Dino Zoff's 5–2–1–2 system largely deviated from the defensive-minded system of his predecessors who were in charge of the Italian national side by introducing younger players and adopting a more attractive and offensive-minded approach,[17][24][25] he also made use of a sweeper, a tight back-line, and put Catenaccio to good use for Italy in the semi-final of UEFA Euro 2000 against co-hosts Netherlands, when the team went down to ten men; despite coming under criticism in the media for his defensive playing style during the match, following a penalty shoot-out victory after a 0–0 draw, he secured a place in the final.[21][26][27][28][29] In the final, Italy only lost on the golden goal rule to France.[30][31]

Previously, Azeglio Vicini, on the other hand, had led Italy to the semi-finals of both UEFA Euro 1988 and the 1990 FIFA World Cup, on home soil, thanks to a more attractive, offensive-minded possession based system, which was combined with a solid back-line and elements of the Italian zona mista approach (or "Gioco all'Italiana"), which was a cross between zonal marking and man-marking systems, such as catenaccio. Despite their more aggressive attacking approach under Vicini during the latter tournament, Italy initially struggled in the first round, before recovering their form in the knock-out stages, and produced small wins in five hard-fought games against defensive sides, in which they scored little but risked even less, totalling only seven goals for and none against leading up to the semi-finals of the competition. Italy would then lose a tight semifinal on penalties following a 1–1 draw to Argentina, due in no small part to a more defensive strategy from Carlos Bilardo, who then went on to lose the final 1–0 to a much more offensive-minded Germany side led by manager Franz Beckenbauer. Italy then claimed the bronze medal match with a 2–1 victory over England.[32][33][34][35][36][37] Vicini's successor as the Italian national side's manager, Arrigo Sacchi, also attempted to introduce his tactical philosophy, which had been highly successful with Milan, to the Italian national team, namely an aggressive high-pressing system, which used a 4–4–2 formation, an attractive, fast, attacking, and possession-based playing style, and which also used innovative elements such as zonal marking and a high defensive line playing the offside trap. Italy struggled to replicate the system successfully and encountered mixed results: under Sacchi, Italy reached the final of the 1994 FIFA World Cup after a slow start, only to lose on penalties following a 0–0 draw with Brazil, but later also suffered a first-round exit at Euro 1996.[38][39][40][41][42]

At the 1978 FIFA World Cup, Enzo Bearzot's Italian side often adopted an attractive, offensive-minded possession game based on passing, creativity, movement, attacking flair, and technique, due to the individual skill of his players; the front three would also often change positions with one another, in order to disorient the opposing defenders. Italy finished the tournament in fourth place, a result they replicated two years later at UEFA Euro 1980 on home soil. At the 1982 FIFA World Cup, he a adopted a more flexible and balanced tactical approach, which was based on the zona mista system, and which used a fluid 4–3–3 formation. While the team were organised and highly effective defensively, they were also capable of getting forward and scoring from quick counter-attacks. The system proved to be highly effective as Italy went on to win the title.[29][43][44]

However, Catenaccio has also had its share of success stories in recent years. Trapattoni himself successfully employed aspects of the system in securing a Portuguese Liga title with Benfica in 2005. German coach Otto Rehhagel also used a similarly defensive approach for his Greece side in UEFA Euro 2004, going on to surprisingly win the tournament despite Greece being considered as underdogs prior to the tournament.[45]

Similarly, although Italy successfully used a more offensive-minded approach under manager Marcello Lippi during the 2006 FIFA World Cup, which saw a record ten of the team's 23 players find the back of the net, with the side scoring 12 goals in total as they went on to claim the title, the team's organised back-line only conceded two goals, neither of which came in open play.[46][47] Notwithstanding their more attacking minded playing style throughout the tournament, when Italy was reduced to ten men in the 50th minute of the 2nd round match against Australia, following Marco Materazzi's red card, coach Lippi changed the Italians' formation to a defensive orientation which caused the British newspaper The Guardian to note that "the timidity of Italy's approach had made it seem that Helenio Herrera, the high priest of Catenaccio, had taken possession of the soul of Marcello Lippi." The ten-man team was playing with a 4–3–2 scheme, just a midfielder away from the team's regular 4–4–2 system. In a tightly-contested match, Italy went on to keep a clean sheet and earned a 1–0 victory through a controversial injury-time penalty.[48]

Legacy

Although pure catenaccio is no longer as commonplace in Italian football, the stereotypical association of ruthless defensive tactics with the Serie A and the Italian national team continues to be perpetuated by foreign media, particularly with the predominantly Italian defences of A.C. Milan of the 1990s and Juventus F.C. from the 2010s onwards being in the spotlight.[49] Rob Bagchi wrote in British newspaper The Guardian: "Italy has also produced defenders with a surplus of ability, composure and intelligence. For every Gentile there was an Alessandro Nesta."[50] Critics and foreign footballers who have played in the Serie A have described Italian defenders as being "masters of the dark arts"[51][52][53] motivated by a Machiavellian philosophy of winning a game at all costs by cunning and calculating methods.[54] Historian John Foot summed up the mentality: "...the tactics are a combination of subtlety and brutality. [...] The 'tactical foul' is a way of life for Italian defenders".[55]

See also

| Look up catenaccio in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Zona mista

- Formation (association football)

- Football tactics and skills

Notes

- Elbech, Søren Florin. "Background on the Intertoto Cup". Mogiel.net (Pawel Mogielnicki). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Andy Gray with Jim Drewett. Flat Back Four: The Tactical Game. Macmillan Publishers Ltd, London, 1998.

- cbcsports.com 1962 Chile

- fifa.com Intercontinental Cup 1969

- "What Nereo Rocco would say about AC Milan and the Azzurri". Calciomercato. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "El Paròn Nereo Rocco, l'allenatore della prima Coppa Campioni" (in Italian). Pianeta Milan. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Helenio Herrera: More than just catenaccio". www.fifa.com. FIFA.com. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- "Mazzola: Inter is my second family". FIFA.com. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- "La leggenda della Grande Inter" [The legend of the Grande Inter] (in Italian). Inter.it. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- "La Grande Inter: Helenio Herrera (1910-1997) – "Il Mago"" (in Italian). Sempre Inter. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- "Great Team Tactics: Breaking Down Helenio Herrera's 'La Grande Inter'". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Fox, Norman (11 November 1997). "Obituary: Helenio Herrera – Obituaries, News". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Wilson, Jonathan (22 September 2009). "The Question: Could the sweeper be on his way back?". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Will Tidey (8 August 2012). "4-2-3-1 Is the New Normal, but Is Serie A's 3-5-2 the Antidote?". BleacherReport.com. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Fleming, Scott (26 June 2012). "Prandelli's revolution". Football Italia. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Hayward, Paul (29 June 2012). "Euro 2012: Cesare Prandelli gets Italy playing with as much heart as head to reach final against Spain". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "L'Italia che cambia: per ogni ct c'è un modulo diverso" (in Italian). sport.sky.it. 20 December 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "Napolitano a Prandelli "Se andava via mi sarei arrabbiato" –" (in Italian). La Repubblica online, www.repubblica.it. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "Mondiali: Trapattoni, "Catenaccio"? Noi giochiamo così..." [World Cup: Trapattoni, "Catenaccio"? We play that way...] (in Italian). ADNKronos. 4 June 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- Foot, John (24 August 2007). Winning at All Costs: A Scandalous History of Italian Soccer. Nation Books. p. 481.

- Bortolotti, Adalberto; D'Orsi, Enzo; Dotto, Matteo; Ricci, Filippo Maria. "CALCIO - COMPETIZIONI PER NAZIONALI" (in Italian). Treccani: Enciclopedia dello Sport (2002). Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Vincenzi, Massimo (19 June 2002). "Vieri la star Maldini il peggiore". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Cassano's last-gasp winner all for nought as Trapattoni pays price for early exit". The Guardian. 23 June 2004. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Veltroni, Walter (12 September 2015). "Zoff: «Berlusconi, Bearzot e Totti. Vi svelo tutto»". Il Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "Juventus rallies around stricken legend Dino Zoff". The Score. 28 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Giancarlo Mola (29 June 2000). "Italia, finale da leggenda Olanda spreca e va fuori" (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Casert, Raf (30 June 2000). "Pele picks France in Euro final". CBC. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- MARCO E. ANSALDO (18 May 1990). "'SUBITO LIBERO DA QUESTA JUVE'". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ANDREA COCCHI (8 July 2012). "Bearzot, un genio della tattica" (in Italian). Mediaset. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "2000, Italia battuta in finale. L'Europeo alla Francia". Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- Ivan Speck (4 July 2000). "Zoff resigned after attack from Berlusconi". espnfc.com. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- MURA, GIANNI (13 October 1991). "L' ITALIA S' ARRENDE E VICINI DICE ADDIO". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- BOCCA, FABRIZIO (31 January 2018). "E' morto Azeglio Vicini, ex ct della Nazionale di calcio". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "La storia della Nazionale ai Mondiali" (in Italian). FIGC. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Glanville, Brian (2018). The Story of the World Cup. Faber and Faber. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-571-32556-6.

After half-time, the game grew harsher, when Klaus Augenthaler was blantanly tripped in the box by Goycoecha, Germany had far stronger claims for a penalty than that which won the match. Sensini bought down Völler in the area Codesal gave a penalty, Argentina protested furiously, and seemed to have a pretty good case.

- Scime, Miguel (7 June 2018). "Por qué el penal más polémico de los Mundiales fue un error en Italia 1990 y hoy no sería cuestionado". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Jones, Grahame L. (28 April 1994). "Losers Cried Foul : Bad Game in '90 Cup Final Might End Up Good for Game". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- "Sacchi to take over at Parma". ESPN.com Soccernet. 9 January 2001. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Vincenzi, Massimo (26 June 2000). "I ct degli altri sport difendono l'Italia di Zoff". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "Gli italiani si dividono tra Zoff e Sacchi". La Repubblica (in Italian). 16 June 2000. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- CATALANO, ANDREA (23 March 2018). "USA 94 E L'ITALIA DI ARRIGO SACCHI" (in Italian). www.rivistacontrasti.it. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Schianchi, Andrea (28 May 2014). "È il Mondiale del Codino. I miracoli e le lacrime". La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "Bearzot: 'Football is first and foremost a game'". FIFA.com. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Brian Glanville (21 December 2010). "Enzo Bearzot obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Tosatti, Giorgio (5 July 2004). "La Grecia nel mito del calcio. Con il catenaccio" [Greece in the football legends. With Catenaccio] (in Italian). Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- "Italy of '06 in numbers". FIFA.com. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Italy conquer the world as Germany wins friends". FIFA.com. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Williams, Richard (27 June 2006). "Totti steps up to redeem erratic Italy". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- David Hytner (17 December 2012). "Santi Cazorla's hat-trick at Reading gives Arsène Wenger breathing space". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Rob, Bagchi (4 June 2008). "Dark arts and cool craft of Italy's defensive fraternity". The Guardian.

- Smith, Rory (2010). Mister: The men who taught the world how to beat England at their own game. Simon & Schuster.

- Malyon, Ed (14 June 2016). "Belgium 0-2 Italy: Azzurri stun Red Devils in Lyon thriller - 5 things we learned". Daily Mirror.

- Ridley, Ian (9 October 1997). "Football: Sheringham reveals Italy's dark arts". The Independent.

- Garganese, Carlo (4 March 2014). "Four World Cups and 28 European trophies - why are Italy the most successful football nation in history?". Goal.com.

- Foot, John (2010). Calcio: A History of Italian Football. Harper Perennial.

References

- Giulianotti, Richard, Football: A Sociology of the Global Game. London: Polity Press 2000. ISBN 0-7456-1769-7