British Overseas citizen

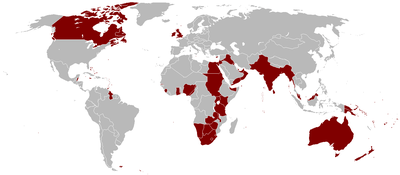

A British Overseas citizen (BOC) is a member of a class of British nationality largely granted under limited circumstances to people connected with former British colonies who do not have close ties to the United Kingdom or its remaining overseas territories. Individuals with this nationality are British nationals and Commonwealth citizens, but not British citizens. Nationals of this class are subject to immigration controls when entering the United Kingdom and do not have the automatic right of abode there or any other country.

| British citizenship and nationality law |

|---|

|

| Introduction |

|

| Nationality classes |

|

| See also |

|

| Relevant legislation |

|

This nationality gives its holders favoured status when they are resident in the United Kingdom, conferring eligibility to vote, obtain citizenship under a simplified process, and serve in public office or non-reserved government positions. About 12,000 British Overseas citizens currently hold active British passports with this status and enjoy consular protection when travelling abroad.[1] However, individuals who only hold BOC nationality are effectively stateless as they are not guaranteed the right to enter the country in which they are nationals.

Background

Before 1983, all citizens of the British Empire held a common nationality. Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKCs) had the unrestricted right to enter and live in the UK.[2] Immigration from the colonies and other Commonwealth countries was gradually restricted by Parliament from 1962 to 1971, when subjects originating from outside of the British Islands first had immigration controls imposed on them when entering the United Kingdom.[3] As Britain withdrew from its remaining overseas possessions during decolonisation, some former colonial subjects remained CUKCs despite the independence of their colonies. After passage of the British Nationality Act 1981, CUKCs were reclassified in 1983 into different nationality groups based on their ancestry, birthplace, and immigration status: CUKCs with the right of abode in the United Kingdom or were closely connected with the UK, Channel Islands, or Isle of Man became British citizens while those connected with a remaining colony became British Dependent Territories citizens (BDTCs). 1.5 million people[4] who could not be reclassified into either of these statuses and were no longer associated with a British territory became British Overseas citizens.[5][6]

Debate over full citizenship rights

The creation of different British nationality classes with a disparity in United Kingdom residency rights between the several classes drew criticism for institutionalising an inherently racist system. The vast majority of people who were classified as British citizens in 1983 were white, while those assigned BDTC or BOC status were predominately Asian.[7] The deprivation of full nationality rights was particularly distressful for the Indian diaspora in Southeast Africa, many of whom migrated to Africa during colonial rule while working in the civil service.[8] As former East African colonies gained independence, aggressive Africanisation policies and an increasingly discriminatory environment in the post-colonial countries against the Asian population caused many among them to seek migration to Britain.[9] While CUKCs without strong ties to the British Islands were already subject to immigration controls starting in 1962, the subdivision of nationality reinforced the idea that British identity depended on race.[10] Parliament ultimately granted remaining BOCs who held no other nationality the right to register as full British citizens in 2002.[11]

Prior to 2002, British Overseas citizens from Malaysia had been able to petition for British citizenship after renouncing Malaysian citizenship.[12] After passage of the British Overseas Territories Act 2002 and the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, these requests were no longer considered. However, a number of Malaysian BOCs continued their applications after this change in immigration policy and renounced their Malaysian citizenship after being given incorrect legal advice. Due to differences in how the governments recognise nationality renunciation, both the British and Malaysian governments consider this group of individuals nationals of the other country and refuse to give them any form of permanent status.[13] Debate over ultimate responsibility for this group of BOCs continues while they remain stateless without a territory that they have a guaranteed right to remain in.[14]

Acquisition and loss

Naturalisation as a British Overseas citizen is not possible. It is expected that BOCs will obtain citizenship in the country they reside in and that the number of active status holders will eventually dwindle until there are none.[15] Currently, it is only possible to transfer BOC status by descent if an individual born to a BOC parent would otherwise be stateless.[16] Due to the broad nature of the governing Acts that determine BOC eligibility, there are a variety of circumstances in which an individual could have acquired the status.[5] These include:

- CUKCs connected with a former colony or protectorate who did not acquire that country's citizenship on independence[17] (applicable particularly to some former colonies, such as Kenya, that did not grant citizenship to CUKCs born or naturalised in that colony)[18]

- persons who remained CUKCs on independence of their colony, but retained the status based on a connection to another colony which subsequently became independent before 1983[19]

- persons who remained CUKCs on independence of their colony (applicable to the former Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca, as well as Cyprus)

- BDTCs connected with Hong Kong who failed to register for British National (Overseas) status and would otherwise have been stateless after the transfer of sovereignty to China on 1 July 1997[20]

- women who acquired CUKC by marriage on or after 28 October 1971[21]

- persons registered as CUKCs by descent before 1983 based on birth in a non-Commonwealth country to a CUKC father[21]

- minor children who acquired CUKC by registration at the British high commission of an independent Commonwealth country on or after 28 October 1971[21]

- eligible descendants of Sophia of Hanover who have never been members of the Catholic Church[22]

Several early independence acts did not remove CUKC status from certain citizens of newly independent states. In the former Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca, around one million Straits Chinese were allowed to continue as CUKCs with Malayan citizenship when the Federation of Malaya became independent in 1957. Consequently, when Malaya merged with North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore to form Malaysia in 1963, CUKC status was not rescinded from individuals already holding Malayan citizenship.[23] Similarly, when Cyprus became independent in 1960, Cypriots who were not resident in Cyprus for the five years leading up to independence and were also living in another Commonwealth country would not have lost CUKC status.[24]

Sophia of Hanover was placed in the English line of succession in 1705 to prevent a reigning Catholic monarch. Because she was German, Parliament passed an Act to naturalise the Electress as a British subject, along with all of her lineal descendants. Although the British Nationality Act 1948 ended the naturalisation of further direct descendants, eligible non-Catholic persons born before 1949 would have already become British subjects. Those individuals would also be able to transmit British nationality to at least one further generation. Because such persons would not automatically have the right of abode in the United Kingdom, some current claimants to British nationality through the Sophia Naturalization Act 1705 would receive British Overseas citizenship.[22]

British Overseas citizenship can be relinquished by a declaration made to the Home Secretary, provided that an individual already possesses or intends to acquire another nationality. BOC status may also be deprived if it was fraudulently acquired. There is no path to restore BOC status once lost.[25]

Rights and privileges

British Overseas citizens are exempted from obtaining a visa or entry certificate when visiting the United Kingdom for less than six months.[26] They are eligible to apply for two-year working holiday visas and do not face annual quotas or sponsorship requirements.[27] When travelling in other countries, they may seek British consular protection.[28] BOCs are not considered foreign nationals when residing in the UK and are entitled to certain rights as Commonwealth citizens.[5] These include exemption from registration with local police[29], voting eligibility in UK elections,[30] and the ability to enlist in the British Armed Forces.[31] British Overseas citizens are also eligible to serve in non-reserved Civil Service posts,[32] be granted British honours, receive peerages, and sit in the House of Lords.[5] If given indefinite leave to remain (ILR), they are eligible to stand for election to the House of Commons and local government.[30] ILR status usually expires if an individual leaves the UK and remains abroad for over two years, but this limitation does not apply to BOCs. Prior to 2002, BOCs who entered the UK on a work permit were automatically given indefinite leave to remain.[33]

BOCs may become British citizens by registration, rather than naturalisation, after residing in the United Kingdom for more than five years and possessing ILR for more than one year. Registration confers citizenship otherwise than by descent, meaning that children born outside of the UK to those successfully registered will be British citizens by descent. Becoming a British citizen has no effect on BOC status; BOCs may also simultaneously be British citizens.[34] BOCs who do not hold and have not lost any other nationality on or after 4 July 2002 are entitled to register as British citizens.[11]

Restrictions

BOCs who hold no other nationality are de facto stateless because they are deprived of entering the country that claims them as nationals.[35] The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 allowed these individuals to register as British citizens, after which statelessness was generally resolved for people who were solely BOCs.[11] However, there remain circumstances in which BOCs are effectively stateless after 4 July 2002, including:

- a BOC is also a citizen of a country that considers acquisition of a foreign passport to be grounds for citizenship deprivation (e.g. Malaysia). A Malaysian-BOC dual national applying for a BOC passport would consequently have their Malaysian citizenship deprived.[36]

- a BOC is also a citizen of a country that only permits dual citizenship for minors and requires renunciation of all other nationalities before a certain age (e.g. Japan). A Japanese-BOC dual national would potentially have their Japanese citizenship revoked at age 22.[37]

United Kingdom

British Overseas citizens are subject to immigration controls and have neither the right of abode or the right to work in the United Kingdom.[28] BOCs are required to pay a "health surcharge" to access National Health Service benefits when residing in the UK for longer than six months.[38]

European Union

Before the United Kingdom withdrew from the European Union on 31 January 2020, full British citizens were European Union citizens.[39] British Overseas citizens have never been EU citizens and did not enjoy freedom of movement in other EU countries.[40] They were,[41] and continue to be, exempted from obtaining visas when visiting the Schengen Area.[39]

References

Citations

- FOI Letter on Passports.

- McKay 2008.

- Evans 1972.

- Chin and Another v Home Secretary [2017] UKUT 15 (IAC), at para. 15

- British Nationality Act 1981.

- Re Canavan [2017] HCA 45, at para. 126

- "Disputed Citizenship Law in Effect in Britain". The New York Times. 2 January 1983. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "UK to right 'immigration wrong'". BBC News. 5 July 2002. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Hansen 1999, pp. 809–810.

- Dixon 1983, p. 162.

- Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

- "Malaysians left 'stateless' in UK after passport gamble backfires". The Daily Telegraph. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Low 2017, pp. 28–31.

- Teh v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWHC 1586 (Admin), at para. 37.

- Hansen 2000, p. 219.

- INPD Letter on BOCs, at para. 19

- "British overseas citizens" (PDF). 1.0. Home Office. 14 July 2017. p. 4. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- White 1988, p. 228.

- "Guide NS" (PDF). Home Office. December 2017. pp. 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "British National (Overseas) and British Dependent Territories Citizens" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "British Nationality: Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "Hanover (Electress Sophia of)" (PDF). Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Alec Douglas-Home, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs (13 November 1972). "Malaysian Citizens". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 25W. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Re Canavan [2017] HCA 45, at para. 126–128

- "Nationality policy: renunciation of all types of British nationality" (PDF). 3.0. Home Office. 30 January 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Check if you need a UK visa". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Youth Mobility Scheme visa (Tier 5)". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Types of British nationality: British overseas citizen". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- "UK visas and registering with the police". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Representation of the People Act 1983.

- "Nationality". British Army. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Civil Service Nationality Rules" (PDF). Cabinet Office. November 2007. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "United Kingdom Passports" (PDF). Immigration Directorates' Instructions (Report). Government of the United Kingdom. November 2004. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Guide B(OTA): Registration as a British citizen" (PDF). Home Office. March 2019. p. 4. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Kaur [2001] C-192/99, at para. 17

- Low 2017, p. 2.

- Steger, Isabella (28 January 2019). "Naomi Osaka will soon be forced to choose whether to play for the US or Japan". Quartz. Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "UK announces health surcharge". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- Regulation (EU) No 2019/592.

- Kaur [2001] C-192/99, at para. 19–27

- Regulation (EU) No 2018/1806 Annex II.

Sources

Publications

- Dixon, David (1983). "Thatcher's People: The British Nationality Act 1981". Journal of Law and Society. 10 (2): 161–180. doi:10.2307/1410230. JSTOR 1410230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, J. M. (1972). "Immigration Act 1971". The Modern Law Review. 35 (5): 508–524. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.1972.tb02363.x. JSTOR 1094478.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hansen, Randall (2000). Citizenship and Immigration in Post-war Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924054-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hansen, Randall (1999). "The Kenyan Asians, British Politics, and the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, 1968". The Historical Journal. 42 (3): 809–834. JSTOR 3020922.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Low, Choo Chin (2017). Report on citizenship law : Malaysia and Singapore (Report). European University Institute. hdl:1814/45371.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKay, James (2008). "The Passage of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, a Case-Study of Backbench Power". Observatoire de la société britannique (6): 89–108. doi:10.4000/osb.433.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Robin M. (1988). "Nationality Aspects of the Hong Kong Settlement". Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law. 20 (1): 225–251.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Case law

- Chin and Another v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] UKUT 15 (IAC), Upper Tribunal (UK)

- Re Canavan [2017] HCA 45 (27 October 2017), High Court (Australia)

- Teh v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWHC 1586, High Court (England and Wales)

- The Queen v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte: Manjit Kaur [2001] EUECJ C-192/99, Case C-192/99, European Court of Justice

Legislation

- Regulation (EU) No 2018/1806 of 14 November 2018 listing the third countries whose nationals must be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt from that requirement

- Regulation (EU) No 2019/592 of 10 April 2019 amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1806 listing the third countries whose nationals must be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt from that requirement, as regards the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the Union

- "British Nationality Act 1981", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1981 c. 61

- "Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002: Section 12", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2002 c. 41 (s. 12)

- "Representation of the People Act 1983: Section 4", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1983 c. 2 (s. 4)

Correspondence

- Director, Immigration and Nationality Policy Directorate (19 June 2002). "British Overseas citizens – Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Bill" (PDF). Letter to Beverley Hughes and the Home Secretary. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Smith, T (11 February 2020). "Freedom of Information Request" (PDF). Letter to Luke Lo. HM Passport Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.