Black-headed gull

The black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) is a small gull that breeds in much of the Palearctic including Europe and also in coastal eastern Canada. Most of the population is migratory and winters further south, but some birds reside in the milder westernmost areas of Europe. Some black-headed gulls also spend the winter in northeastern North America, where it was formerly known as the common black-headed gull. As is the case with many gulls, it was previously placed in the genus Larus.

| Black-headed gull | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Adult summer plumage | |

| Adult winter plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Chroicocephalus |

| Species: | C. ridibundus |

| Binomial name | |

| Chroicocephalus ridibundus (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| |

| Map of eBird reports of C. ridibundus Year-Round Range Summer Range Winter Range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Larus ridibundus Linnaeus, 1766 | |

The genus name Chroicocephalus is from Ancient Greek khroizo, "to colour", and kephale, "head". The specific ridibundus is Latin for "laughing", from ridere "to laugh".[2]

The black-headed gull displays a variety of compelling behaviours and adaptations. Some of these include removing eggshells from ones nest after hatching, begging coordination between siblings, differences between sexes, conspecific brood parasitism, and extra-pair paternity. They are an overwintering species, found in a variety of different habitats.[3]

Description

This gull is 38–44 cm (15–17 in) long with a 94–105 cm (37–41 in) wingspan. In flight, the white leading edge to the wing is a good field mark. The summer adult has a chocolate-brown head (not black, although does look black from a distance), pale grey body, black tips to the primary wing feathers, and red bill and legs. The hood is lost in winter, leaving just two dark spots. Immature birds have a mottled pattern of brown spots over most of the body.[4] It breeds in colonies in large reed beds or marshes, or on islands in lakes, nesting on the ground. Like most gulls, it is highly gregarious in winter, both when feeding or in evening roosts. It is not a pelagic species and is rarely seen at sea far from coasts.

The black-headed gull is a bold and opportunistic feeder. It eats insects, fish, seeds, worms, scraps, and carrion in towns, or invertebrates in ploughed fields with equal relish. It is a noisy species, especially in colonies, with a familiar "kree-ar" call. Its scientific name means laughing gull.

This species takes two years to reach maturity. First-year birds have a black terminal tail band, more dark areas in the wings, and, in summer, a less fully developed dark hood. Like most gulls, black-headed gulls are long-lived birds, with a maximum age of at least 32.9 years recorded in the wild, in addition to an anecdote now believed of dubious authenticity regarding a 63-year-old bird.[5]

Distribution

To be found over much of Europe, except Spain, Italy and Greece.[4] It is also found in across the Palearctic to Japan and E China.[6] It is an occasional visitor to the east coast of North America.

And also in some Caribbean islands.

Behaviour

Eggshell removal

Eggshell removal is a behaviour seen in birds once the chicks have hatched, observed mostly to reduce risk of predation.[7] Removing the eggshell acts as a way of camouflage to avoid predators seeing the nest.[8] The further away egg shells are from the nest, the lower the predation risk.[7] Black-headed gull eggs experience predation from different species of birds, foxes, stoats, and even other black-headed gulls. Although mothers show some form of aggressiveness when a predator is near, in the first 30 minutes, wet chicks can be easily taken by other black-headed gulls after hatching when the parents of the wet chick are distracted.[8]

Black headed gulls also carry away other objects that do not belong in the nest. The removal of eggshells and other objects is important not only in the incubation period but also during the first few days after the eggs hatch. However, the removal process seems to increase as time goes on.[9] The removal is done by both the male and female parents, normally lasts a few seconds and is done three times a year.[8]

A black-headed gull is able to differentiate an egg shell from an egg by acknowledging its thin, serrated, white, edge. Therefore, the weight of the egg or eggshell does not play a role when determining its value.[10]

Earlier eggshell removal hypotheses

Other hypotheses have attempted to explain the survival value of black-headed gulls removing their eggshells from the nest, including:[8]

- The sharp edges of the shells after hatching could harm the chicks[8]

- The eggshell could somehow intrude during the brooding[8]

- The eggshell could slip over the unhatched egg, creating a double shell[8]

- Some of the moist organic material left from the shell could lead to a production of bacteria and mould[8]

Breeding

Begging coordination between siblings

Black-headed gulls feed their young by regurgitating it onto the ground, rather than into each chick one at a time. The parents tend to accommodate their regurgitation amounts for how intense the nest begging is, from both an individual chick or a group of chicks begging together. Chicks who are siblings, have learned this behaviour and begin synchronizing their begging signals to decrease the costs as an individual and increase the benefits as a whole.[11] The rate of parental food regurgitation to chicks increases with begging intensity.[12]

The amount and response of begging signals differs throughout the nestling period. Usually, there is 3-5 begging events/hour, each lasting around one minute.[11] High intensity begging behaviour appears at the end of the first week in the nest, but the coordination between multiple chicks emerge during the last week of the nestling period. The more siblings present, the more they coordinate their begging while decreasing the number of begging.[11]

Sex differences

Male chicks have less of a chance of survival when compared to female chicks. Black-headed gulls are a sexually size-dimorphic species, so the larger sex is at a disadvantage when the amount of food sources are low.[13]

Male birds are more likely to be born in the first egg and female birds are more likely to be born in the third. The position of a female black-headed gull in response to the food available when laying the eggs can predict the offsprings characteristics.[14]

Conspecific brood parasitism

Conspecific brood parasitism is a behaviour that occurs when females lay their eggs in another females nest, of the same species.[15] It can reduce the cost of incubation and nestling young by passing it on to another bird. Black-headed gulls usually lay three egg clutches, and the first two are normally larger than the third.[15] The third egg normally has the lowest survival rate, while the first or second are usually the parasitic eggs.[15]

Most of the egg dumping occurs within the beginning of the egg laying period. The parasitic eggs being laid in another conspecifics nest increases the chance of hatching and may occur because of nest desertion or a nest being taken over by another bird.[15]

Multiple eggs in a nest from different mothers may also result from intra-specific nest parasitism,[16] joint female nesting,[17] and nest takeover.[18] Intra-specific nest parasitism is a disadvantage to the hosts because the female could end up taking care of the parasitic chicks over her own and therefore neglecting them and reducing their fitness. Another disadvantage for the host is that incubating more chicks than their own takes up more energy.[19]

Extra-pair paternity

The rate of extra-pair paternity (EPP) has a large variation between populations of black-headed gulls. It is primarily a context-dependent strategy, meaning not all black headed gulls experience this behaviour.[20] The variation between populations of extra-pair paternity can be explained by the variation it has on the advantages and disadvantages it has on a female, as well, as the variation in pressure on a females choice.[21]

The differences in the rate of EPP may be determined by multiple different factors: life history traits, ecological factors or different behavioural strategies of males.[20]

Central–periphery gradient within colonies

Egg-laying can be earlier in Black-headed Gulls nesting in the centre of the colony, with central pairs tending to lay larger eggs, which have a higher hatching success, than pairs nesting at the periphery of the colony. Centrally nesting individuals have also been found to be in better condition and have higher genetic quality.[22]

Walking displays

Black-headed gulls display both head-bobbing walking (HBW) and non-bobbing walking (NBW). Head-bobbing walking is expressed by a hold phase and a thrust phase. The hold phase in black-headed gulls occurs mainly during the single support phase and is when the bird balances its head to equal the environment.[23] Head-bobbing walking occurs during a seeking type foraging by walking through water and includes benefits such as enhancing motion and pattern detection and gathering depth information from motion parallax during the thrust phase.[23] Non-bobbing walking occurs when black-headed gulls are displaying a waiting behaviour while foraging on flat surfaces.[23]

Uses

The eggs of the black-headed gull are considered a delicacy by some in the UK and are eaten hard boiled.[24][25]

Synchronization

Observations on the behavior of black-headed gulls show that black-headed gulls individuals synchronize their activity with other black-headed gulls neighbors. Synchronization in black-headed gulls groups is dependent on the distance between the black-headed gulls members.[26]

Gallery

Ringing of black-headed gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Laridae) nestling

Ringing of black-headed gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Laridae) nestling_nesting.jpg) nesting, Rye Harbour SSSI

nesting, Rye Harbour SSSI_chick.jpg) chick, Rye Harbour SSSI

chick, Rye Harbour SSSI_chicks.jpg) chicks swimming, Rye Harbour SSSI

chicks swimming, Rye Harbour SSSI Adult winter plumage in St James's Park, London

Adult winter plumage in St James's Park, London Adult breeding plumage

Adult breeding plumage Adult summer plumage, North Devon coast, England

Adult summer plumage, North Devon coast, England Juvenile plumage

Juvenile plumage- Adult summer plumage, Pangong Tso

In flight

In flight_juvenile.jpg) Juvenile at Farmoor Reservoir, Oxfordshire

Juvenile at Farmoor Reservoir, Oxfordshire At Farmoor Reservoir, Oxfordshire

At Farmoor Reservoir, Oxfordshire At Farmoor Reservoir, Oxfordshire

At Farmoor Reservoir, Oxfordshire In Baku, Azerbaijan

In Baku, Azerbaijan First winter plumage, at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire

First winter plumage, at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire ID composite

ID composite in flight near Großenbrode, Schleswig-Holstein. The bird is in a near-vertical position.

in flight near Großenbrode, Schleswig-Holstein. The bird is in a near-vertical position.

References

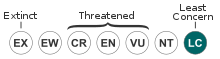

- Butchart, S.; Symes, A. (2012). "Larus ridibundus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T22694420A38851158. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22694420A38851158.en.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 104, 171. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Scott, Paul; Duncan, Peter; Green, Jonathan A. (2 January 2015). "Food preference of the Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus differs along a rural–urban gradient". Bird Study. 62 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1080/00063657.2014.984655. ISSN 0006-3657.

- Peterson, R., Mountfort, G. and Hollom, P.A.D.1967. A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. Collins

- "Longevity, ageing, and life history of Chroicocephalus ridibundus". The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Attenborough, D. 1998. The Life of Birds. BBC ISBN 0563-38792-0

- SORDAHL, TEX A. (2006). "Field Experiments on Eggshell Removal by Mountain Plovers". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 118 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1676/1559-4491(2006)118[0059:feoerb]2.0.co;2. ISSN 1559-4491.

- Houghton, J.C.W.; Feekes, F.; Broekhuysen, G.J.; Tinbergen, N.; Szulc, E.; Kruuk, H. (1962). "Egg Shell Removal By the Black-Headed Gull, Larus Ridibundus L.; a Behaviour Component of Camouflage". Behaviour. 19 (1–2): 74–116. doi:10.1163/156853961x00213. ISSN 0005-7959.

- Beer, C.G. (1963). "Incubation and Nest-Building Behaviour of Black-Headed Gulls Iv: Nest-Building in the Laying and Incubation Periods". Behaviour. 21 (3–4): 155–176. doi:10.1163/156853963x00158. ISSN 0005-7959.

- Tinbergen, N.; Kruuk, H.; Paillette, M. (1962). "Egg shell removal by the Black-headed Gull (Larus r. ridibundus L.) II. The effects of experience on the response to colour". Bird Study. 9 (2): 123–131. doi:10.1080/00063656209476020. ISSN 0006-3657.

- Blanc, Alain; Ogier, Nicolas; Roux, Angélique; Denizeau, Sébastien; Mathevon, Nicolas (2010). "Begging coordination between siblings in Black-headed Gulls". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 333 (9): 688–693. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2010.06.002. ISSN 1631-0691. PMID 20816649.

- Mathevon, N.; Charrier, I. (7 May 2004). "Parent–offspring conflict and the coordination of siblings in gulls". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 271 (suppl_4): S145–S147. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0117. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1810040. PMID 15252967.

- MULLER, WENDT; GROOTHUIS, TON G. G.; EISING, CORINE M.; DIJKSTRA, COR (2005). "An experimental study on the causes of sex-biased mortality in the black-headed gull - the possible role of testosterone" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology. 74 (4): 735–741. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00964.x. ISSN 0021-8790.

- Lezalova, Radka; Tkadlec, Emil; Obornik, Miroslav; Simek, Jaroslav; Honza, Marcel (7 September 2005). "Should males come first? The relationship between offspring hatching order and sex in the black-headed gull Larus ridibundus". Journal of Avian Biology. 0: 060118052425010––. doi:10.1111/j.2005.0908-8857.03466.x. ISSN 0908-8857.

- Duda, Norbert; Chętnicki, Włodzimierz (2012). "Conspecific Brood Parasitism is Biased Towards Relatives in the Common Black-Headed Gull". Ardea. 100 (1): 63–70. doi:10.5253/078.100.0110. ISSN 0373-2266.

- YOM-TOV, YORAM (28 June 2008). "An updated list and some comments on the occurrence of intraspecific nest parasitism in birds". Ibis. 143 (1): 133–143. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2001.tb04177.x. ISSN 0019-1019.

- Vehrencamp, Sandra L. (2000). "Evolutionary routes to joint-female nesting in birds". Behavioral Ecology. 11 (3): 334–344. doi:10.1093/beheco/11.3.334. ISSN 1465-7279.

- Waldeck, Peter; Andersson, Malte (2006). "Brood Parasitism and Nest Takeover in Common Eiders". Ethology. 112 (6): 616–624. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2005.01187.x. ISSN 0179-1613.

- Duda, Norbert; Ch e ˛ tnicki, Wlodzimierz; Waldeck, Peter; Andersson, Malte (7 January 2008). "Multiple maternity in black-headed gull Larus ridibundus clutches as revealed by protein fingerprinting". Journal of Avian Biology. 0: 080205233540538–0. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04111.x. ISSN 0908-8857.

- Indykiewicz, Piotr; Podlaszczuk, Patrycja; Minias, Piotr (2017). "Extra-pair paternity in the black-headed gull: is it exceptional among colonial waterbirds?". Behaviour. 154 (11): 1081–1099. doi:10.1163/1568539x-00003459. ISSN 0005-7959.

- Petrie, Marion; Kempenaers, Bart (1998). "Extra-pair paternity in birds: explaining variation between species and populations". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 13 (2): 52–58. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01232-9. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 21238200.

- Indykiewicz, P.; Podlaszczuk, P.; Kamiński, M.; Włodarczyk, R.; Minias, P. (2019). "Central–periphery gradient of individual quality within a colony of Black‐headed Gulls". Ibis. 161 (4): 744–758. doi:10.1111/ibi.12689.

- Fujita, Masaki (24 January 2006). "Head-bobbing and non-bobbing walking of black-headed gulls (Larus ridibundus)". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 192 (5): 481–488. doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0083-4. ISSN 0340-7594. PMID 16432727.

- Copping, Jasper (28 March 2009). "Top restaurants face shortage of seagull eggs". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- "Conservation (Natural Habitats&c" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2010.

- Evans, Madeleine H. R., et al. “Black-Headed Gulls Synchronise Their Activity with Their Nearest Neighbours.” Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28378-x.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chroicocephalus ridibundus. |

| Look up black-headed gull in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Black-headed gull stamps from many countries at bird-stamps.org

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.0 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Feathers of Black-headed Gull (Larus ridibundus) at Ornithos.de

- BirdLife species factsheet for Larus ridibundus

- "Chroicocephalus ridibundus". Avibase.

- "Common black-headed gull media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Black-headed gull photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Larus ridibundus at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Black-headed gull on Xeno-canto.

- Chroicocephalus ridibundus in the Flickr: Field Guide Birds of the World

- Black-headed gull media from ARKive