Ancient higher-learning institutions

A variety of ancient higher-learning institutions were developed in many cultures to provide institutional frameworks for scholarly activities. These ancient centres were sponsored and overseen by courts; by religious institutions, which sponsored cathedral schools, monastic schools, and madrasas; by scientific institutions, such as museums, hospitals, and observatories; and by individual scholars. They are to be distinguished from the Western-style university, an autonomous organization of scholars that originated in medieval Europe[1] and has been adopted in other regions in modern times (see list of oldest universities in continuous operation).[2]

Europe and the Near East

Hellenism

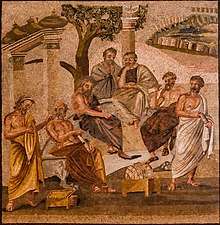

The Platonic Academy (sometimes referred to as the University of Athens),[3][4] founded ca. 387 BC in Athens, Greece, by the philosopher Plato, lasted 916 years (until AD 529) with interruptions.[5] It was emulated during the Renaissance by the Florentine Platonic Academy, whose members saw themselves as following Plato's tradition.

Around 335 BC, Plato's successor Aristotle founded the Peripatetic school, the students of which met at the Lyceum gymnasium in Athens. The school ceased in 86 BC during the famine, siege and sacking of Athens by Sulla.[6]

During the Hellenistic period, the Museion in Alexandria (which included the Library of Alexandria) became the leading research institute for science and technology from which many Greek innovations sprang. The engineer Ctesibius (fl. 285–222 BC) may have been its first head. It was suppressed and burned between AD 216 and 272, and the library was destroyed between 272 and 391.

The reputation of these Greek institutions was such that at least four central modern educational terms derive from them: the academy, the lyceum, the gymnasium and the museum.

Christian Europe

The University of Constantinople, founded as an institution of higher learning in 425, educated graduates to take on posts of authority in the imperial service or within the Church.[7] It was reorganized as a corporation of students in 849 by the regent Bardas of emperor Michael III, is considered by some to be the earliest institution of higher learning with some of the characteristics we associate today with a university (research and teaching, auto-administration, academic independence, et cetera). If a university is defined as "an institution of higher learning" then it is preceded by several others, including the Academy that it was founded to compete with and eventually replaced. If the original meaning of the word is considered "a corporation of students" then this could be the first example of such an institution. The Preslav Literary School and Ohrid Literary School were the two major literary schools of the First Bulgarian Empire.

In Western Europe during the Early Middle Ages, bishops sponsored cathedral schools and monasteries sponsored monastic schools, chiefly dedicated to the education of clergy. The earliest evidence of a European episcopal school is that established in Visigothic Spain at the Second Council of Toledo in 527.[8] These early episcopal schools, with a focus on an apprenticeship in religious learning under a scholarly bishop, have been identified in Spain and in about twenty towns in Gaul during the 6th and 7th centuries.[9]

In addition to these episcopal schools, there were monastic schools which educated monks and nuns, as well as future bishops, at a more advanced level.[10] Around the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, some of them developed into autonomous universities. A notable example is when the University of Paris grew out of the schools associated with the Cathedral of Notre Dame, the Monastery of Ste. Geneviève, and the Abbey of St. Victor.[11][12]

Asia

Ancient India

Major Buddhist monasteries (mahaviharas), notably those at Pushpagiri, Nalanda, Valabhi, and Taxila, included schools that were some of the primary institutions of higher learning in ancient India.

Pushpagiri

The school in Pushpagiri was established in the 3rd century AD as present Odisha, India. As of 2007, the ruins of this Mahavihara had not yet been fully excavated. Consequently, much of the Mahavihara's history remains unknown. Of the three Mahavihara campuses, Lalitgiri in the district of Cuttack is the oldest. Iconographic analysis indicates that Lalitgiri had already been established during the Shunga period of the 2nd century BC, making it one of the oldest Buddhist establishments in the world. The Chinese traveller Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang), who visited it in AD 639, as Puphagiri Mahavihara,[13][14] as well as in medieval Tibetan texts. However, unlike Takshila and Nalanda, the ruins of Pushpagiri were not discovered until 1995, when a lecturer from a local college first stumbled upon the site.[15][16] The task of excavating Pushpagiri's ruins, stretching over 58 hectares (143 acres) of land, was undertaken by the Odisha Institute of Maritime and South East Asian Studies between 1996 and 2006. It is now being carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).[17] The Nagarjunakonda inscriptions also mention about this learning center. [18][19]

Nalanda

Nalanda was established in the fifth century AD in Bihar, India[22] and survived until circa 1200 AD. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war.[23]

The center had eight separate compounds, ten temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, housing 10,000 students in the school’s heyday and providing accommodation for 2,000 professors.[24] Nalanda attracted pupils and scholars from Sri Lanka, Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey, who left accounts of the center.[25]

In 2014 a modern Nalanda University was launched in nearby Rajgir.

Taxila

Ancient Taxila or Takshashila, in ancient Gandhara, was an early Hindu and Buddhist centre of learning. According to scattered references that were only fixed a millennium later, it may have dated back to at least the fifth century BC.[26] Some scholars date Takshashila's existence back to the sixth century BC.[27] The school consisted of several monasteries without large dormitories or lecture halls where the religious instruction was most likely still provided on an individualistic basis.[26]

Takshashila is described in some detail in later Jātaka tales, written in Sri Lanka around the fifth century AD.[28]

It became a noted centre of learning at least several centuries BC, and continued to attract students until the destruction of the city in the fifth century AD. Takshashila is perhaps best known because of its association with Chanakya. The famous treatise Arthashastra (Sanskrit for The knowledge of Economics) by Chanakya, is said to have been composed in Takshashila itself. Chanakya (or Kautilya),[29] the Maurya Emperor Chandragupta[30] and the Ayurvedic healer Charaka studied at Taxila.[31]

Generally, a student entered Takshashila at the age of sixteen. The Vedas and the Eighteen Arts, which included skills such as archery, hunting, and elephant lore, were taught, in addition to its law school, medical school, and school of military science.[31]

Vikramashila

Vikramashila was one of the two most important centres of learning in India during the Pala Empire, along with Nalanda. Vikramashila was established by King Dharmapala (783 to 820) in response to a supposed decline in the quality of scholarship at Nalanda. Atisha, the renowned pandita, is sometimes listed as a notable abbot. It was destroyed by the forces of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji around 1200.[32]

Vikramashila is known to us mainly through Tibetan sources, especially the writings of Tāranātha, the Tibetan monk historian of the 16th–17th centuries.[33]

Vikramashila was one of the largest Buddhist universities, with more than one hundred teachers and about one thousand students. It produced eminent scholars who were often invited by foreign countries to spread Buddhist learning, culture and religion. The most distinguished and eminent among all was Atisha Dipankara, a founder of the Sarma traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Subjects like philosophy, grammar, metaphysics, Indian logic etc. were taught here, but the most important branch of learning was tantrism.

Other

Further centres include Telhara in Bihar[34] (probably older than Nalanda[35]), Odantapuri, in Bihar (circa 550 - 1040), Somapura Mahavihara, in Bangladesh (from the Gupta period to the Turkic Muslim conquest), Sharada Peeth, Pakistan, Jagaddala Mahavihara, in Bengal (from the Pala period to the Turkic Muslim conquest), Nagarjunakonda, in Andhra Pradesh, Vikramashila, in Bihar (circa 800-1040), Valabhi, in Gujarat (from the Maitrak period to the Arab raids), Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh (eighth century to modern times), Kanchipuram, in Tamil Nadu, Manyakheta, in Karnataka, Mahavihara, Abhayagiri Vihāra, and Jetavanaramaya, in Sri Lanka.

East Asia

In China, the ancient imperial academy known as Taixue was established by the Han Dynasty. It was intermittently inherited by succeeding Chinese dynasties up until the Qing dynasty, in some of which the name was changed to Guozixue or Guozijian. Peking University (Imperial University of Peking) established in 1898 is regarded as the replacement of Taixue. By 725 AD, Shuyuan or Academies of Classical Learning were private learning institutions established during the medieval Chinese Tang dynasty.

In Japan, Daigakuryo was founded in 671 and Ashikaga Gakko was founded in the 9th century and restored in 1432.

In Korea, Taehak was founded in 372 and Gukhak was established in 682. Seowons were private institutions established during the Joseon dynasty which combined functions of a Confucian shrine and a preparatory school. The Seonggyungwan was founded by in 1398 to offer prayers and memorials to Confucius and his disciples, and to promote the study of the Confucian canon. It was the successor to Gukjagam from the Goryeo Dynasty (992). It was reopened as a private Western-style university in 1946.

Ancient Persia

The Academy of Gondishapur was established in the 3rd century AD under the rule of Sassanid kings and continued its scholarly activities up to four centuries after Islam came to Iran. It was an important medical centre of the 6th and 7th centuries and a prominent example of higher education model in pre-Islam Iran.[36] When the Platonic Academy in Athens was closed in 529, some of its pagan scholars went to Gundishahpur, although they returned within a year to Byzantium.

See also

- Madrasah

- Medieval university

- Nezamiyeh

- History of Academia, Academy, University

- Pirivena

References

- Furley, David (2003a), "Peripatetic School", in Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-860641-9

- Irwin, T. (2003), "Aristotle", in Craig, Edward (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge

- Lynch, J. (1997), "Lyceum", in Zeyl, Donald J.; Devereux, Daniel; Mitsis, Phillip (eds.), Encyclopedia of Classical Philosophy, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-28775-9

- Riché, Pierre. Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1978. ISBN 0-87249-376-8.

Notes

- Stephen C. Ferruolo, The Origins of the University: The Schools of Paris and Their Critics, 1100-1215, (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1985) pp. 4-5 ISBN 0-8047-1266-2

- Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (1994). A History of the University in Europe: Universities in the middle ages / ed. Hilde de Ridder-Symoens. ISBN 978-0-521-36105-7.

- Ellwood P. Cubberley (2004). The History of Education. Kessinger Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4191-6605-1.

- Howard Eugene Wilson (1939). Harvard Educational Review. Harvard University.

- C. Leor Harris (1981). Evolution, Genesis and Revelations: With Readings from Empedocles to Wilson. SUNY Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4384-0584-1.

- 336 BC: Furley 2003a, p. 1141; 335 BC: Lynch 1997, p. 311; 334 BC: Irwin 2003

- Constantinides, C. N. (2003). "Rhetoric in Byzantium: Papers from the Thirty-Fifth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies". In Jeffreys, Elizabeth (ed.). Teachers and students of rhetoric in the late Byzantine period. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 39–53. ISBN 0-7546-3453-1.

- Riché, Education and Culture, pp. 126-7.

- Riché, Education and Culture, pp. 282-90.

- Riché, Education and Culture, pp. 290-8.

- Pedersen, Olaf (1997). The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe. pp. 130–31. ISBN 978-0-521-59431-8.

- The rise of universities. Cornell University Press. 1957. pp. 12–16. ISBN 978-0-8014-9015-6.

- Binayak Misra (1986). Indian culture and cult of Jagannātha. Punthi Pustak. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "Orissa's treasures". February 2005. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- H. K. Mohapatra (December 2004). "Great Heritages of Orissa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2009.

- "ASI hope for hill heritage – Conservation set to start at Orissa site". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. 29 January 2007.

- "Archaeological Survey of India takes over Orissa Buddhist site". 17 November 2006.

- Thomas E. Donaldson (2001). Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa: Text. Abhinav Publications. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-81-7017-406-6. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Pratapaditya Pal; Marg Publications (31 March 2001). Orissa revisited. Marg Publications. ISBN 978-81-85026-51-0. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1965). Education in Ancient India, Sixth, Varanasi: Nand Kishore & Bros.

- "Really Old School," Garten, Jeffrey E. New York Times, 9 December 2006.

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1965). Education in Ancient India, Sixth, Varanasi: Nand Kishore & Bros.

- OpEd in New York Times: Nalanda University

- "Official website of Nalanda University". Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "History and Revival". Nalanda University. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Scharfe, Hartmut; Bronkhorst, Johannes; Spuler, Bertold; Altenmüller, Hartwig (2002). Handbuch Der Orientalistik: India. Education in ancient India. p. 141. ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8.

- "History of Education", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- Marshall 1975:81

- Kautilya Archived 10 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya And His Times. Motilal Banarsidass Pub. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0.

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1990). Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist. Motilal Banarsidass Pub. pp. 478–489. ISBN 978-81-208-0423-4.

- Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 89.

- "Excavated Remains at Nalanda". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- "TELHARA (NALANDA) EXCAVATION A Brief Report" (PDF). yac.bih.nic.in. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- "Telhara University's ruins older than Nalanda, Vikramshila". firstpost. 14 December 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Salari, H. "University in Iran". paper. jazirehdanesh. Retrieved 13 May 2011.