Charter school

A charter school is a school that receives government funding but operates independently of the established state school system in which it is located.[1][2] It is independent in the sense that it operates according to the basic principle of autonomy for accountability, that it is freed from the rules but accountable for results.[3]

Public vs. private school

There is debate on whether charter schools ought to be described as private schools or state schools.[4] Advocates of the charter model state[5] that they are public schools because they are open to all students and do not charge tuition, while critics cite charter schools' private operation and loose regulations regarding public accountability and labor issues[6] as arguments against the concept.[4] It is also described as a form of public education that is controlled by parents and small constituencies.[3] On the other hand, charter schools are often established, operated, and maintained by for-profit organizations.[7]

By country

Australia

All Australian private schools have received some federal government funding since the 1970s.[8] Since then they have educated approximately 30% of high school students. None of them are charter schools, as all charge tuition fees.

Since 2009, the Government of Western Australia has been trialling the Independent Public School (IPS) Initiative.[9] These public schools have greater autonomy and could be regarded as akin to 'charter' Schools (but the term is not used in Australia).

Canada

The Canadian province of Alberta enacted legislation in 1994 enabling charter schools.[10] The first charter schools under the new legislation were established in 1995: New Horizons Charter School, Suzuki Charter School, and the Centre for Academic and Personal Excellence.[11] As of 2015, Alberta remains the only Canadian province that has enabled charter schools.[12]

There are 23 charter school campuses operated by 13 Alberta charter schools.[13][14] The number of charter schools is limited to a maximum of 15.[15]

Cambodia

In 2015, Charter School first introduced to the Royal Government of Cambodia. This initiative is running by a local NGO called “Kampuchean Action for Primary Education” as the implementor and funded by the Royal Government of Cambodia through the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports. This school is 100% public school which is receiving high investment and the condition of producing high quality performance. This model is a new Public-Private Partnership which the non-state actor plays the implementation and invested from all stakeholders, government, community, and other generous donors. There are three kinds of schools that could invest in the New Generation School (Cambodia Charter School Initiative) 1). New School refers to school where has nothing that means everything has to start to build a new building, recruit school head, administration and teachers and students. 2). Contracting school, refers to a school that failed and lost the number of students who are getting a school to become smaller and smaller. 3). Existing school that school wants to run in a school in a school model or the whole school by starting for a low grade then scale up following until the complete the whole school. This initiative is aiming to 1). Create autonomous public schools governed by strict rules of performance accountability linked to high investment, 2). Create new governance boards, 3). Create an accreditation system, 4). Provide new institutional freedoms, 5). Enable the education system to be more efficient and socially equitable with respect to the teaching and learning process, 6). Improve teaching standards through new approaches, 7). Expand educational services for Cambodian youth. To achieve these objectives, the policy, itself, introduces 15 strategies for implementation; rigorous school selection, partnership (relationship between the state and non-state actors to implement the policy), school accountability, direct controls from national level, teacher incentives, operational autonomy linked with innovation, intensive use of technology to drive innovation, youth empowerment, increased teaching and learning hours, introduced subject-theme, social equity-fund, school in a school model (apply to big school that face a lot challenges regarding to teachers involvement), reduced the pupils and teachers ration, changed individual mindsets, modernized the learning environments. To achieve the above strategies, the following activities should have adhered to the established mechanism, formulation of regulations, financial supports, human resource training, and project implementation process. The policy also introduces the details of implementation on the operational guideline that there are specific guidelines, principles with annexes and frameworks for a local educational authority to adapt and follow.

Chile

Chile has a very long history of private subsidized schooling, akin to charter schooling in the United States. Before the 1980s, most private subsidized schools were religious and owned by churches or other private parties, but they received support from the central government. In the 1980s, the government of Augusto Pinochet promoted neoliberal reforms in the country.[16] In 1981 a competitive voucher system in education was adopted.[17] These vouchers[18] could be used in public schools or private subsidized schools (which can be run for profit). After this reform, the share of private subsidized schools, many of them secular, grew from 18.5% of schools in 1980 to 32.7% of schools in 2001.[19] As of 2012, nearly 60% of Chilean students study in charter schools.[20]

Colombia

Colombia, like Chile, has a long tradition of religious and private schools. With the economic crisis of religious orders, different levels of the state have had to finance these schools to keep them functioning.[21] Also, in some cities such as Bogotá, there are programs of private schools financed by public resources, giving education access to children from poor sectors. These cases, however, are very small and about 60% of children and young people study in private schools paid for by their families. Moreover, private schools have higher quality than public ones.[22]

England and Wales

The United Kingdom established grant-maintained schools in England and Wales in 1988.[23] They allowed individual schools that were independent of the local school authority. When they were abolished in 1998, most turned into foundation schools, which are really under their local district authority but still have a high degree of autonomy.

Prior to the 2010 general election, there were about 200 academies (publicly funded schools with a significant degree of autonomy) in England.[24] The Academies Act 2010 aims to vastly increase this number.

Germany

Due to Art. 7 of the Grundgesetz (German constitution), private schools may only be set up if they do not increase the segregation of pupils by their parents' income class.[25] In return, all private schools are supported financially by government bodies, comparable to charter schools. The amount of control over school organization, curriculum etc. taken over by the state differs from state to state and from school to school. Average financial support given by government bodies was 85% of total costs in 2009.[26] Academically, all private schools must lead their students to the ability to attain standardized, government-provided external tests such as the Abitur.[27]

Hong Kong

Some private schools in Hong Kong receive government subsidy under the Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS).[28] DSS schools are free to design their curriculum, select their own students, and charge for tuition. A number of DSS schools were formerly state schools prior to joining the scheme.

Ireland

Charter schools in Ireland were set up mostly in the 1700s by the Church of Ireland to educate the poor. They were state or charity sponsored, but run by the church. The model to copy was Kilkenny College, but critics like Bernard Mandeville felt that educating too many poor children would lead them to have unrealistic expectations. Notable examples are the Collegiate School Celbridge, Midleton College, Wilson's Hospital School and The King's Hospital.

New Zealand

Charter schools in New Zealand, labelled as Partnership schools | kura hourua,[29] were allowed for after an agreement between the National Party and the ACT Party following the 2011 general election. The controversial legislation passed with a five-vote majority. A small number of charter schools started in 2013 and 2014. All cater for students who have struggled in the normal state school system. Most of the students have issues with drugs, alcohol, poor attendance and achievement. Most of the students are Maori or Pacific Islander. One of the schools is set up as a military academy. One of the schools ran into major difficulties within weeks of starting. It is now being run by an executive manager from Child, Youth and Family, a government social welfare organization, together with a commissioner appointed by the Ministry of Education. 36 organizations have applied to start charter schools.

Norway

As in Sweden, the publicly funded but privately run charter schools in Norway are named friskoler and was formally instituted in 2003, but dismissed in 2007. Private schools have since medieval times been a part of the education system, and is today consisting of 63 Montessori and 32 Steiner (Waldorf) charter schools, some religious schools and 11 non-governmental funded schools like the Oslo International School, the German School Max Tau and the French School Lycée Français, a total of 195 schools.

All charter schools can have a list of admission priorities, but only the non-governmental funded schools are allowed to select their students and to make a profit. The charter schools cannot have entrance exams, and supplemental fees are very restricted. In 2013, a total of 19,105 children were enrolled in privately run schools.[30]

Sweden

The Swedish system of friskolor ("charter schools") was instituted in 1992.[17] These are publicly funded by school vouchers and can be run by not-for-profits as well as for-profit companies.[31] The schools are restricted: for example, they are prohibited from supplementing the public funds with tuition or other fees; pupils must be admitted on a first-come, first-served basis; and entrance exams are not permitted.[32] There are about 900 charter schools throughout the country.[33]

United States

According to the Education Commission of the States, "charter schools are semi-autonomous public schools that receive public funds. They operate under a written contract with a state, district or other entity (referred to as an authorizer or sponsor). This contract – or charter – details how the school will be organized and managed, what students will be expected to achieve, and how success will be measured. Many charters are exempt from a variety of laws and regulations affecting other public schools if they continue to meet the terms of their charters."[35] These schools, however, need to follow State-mandated curriculum and are subject to the same rules and regulations that cover it, although there is flexibility in the way it is designed.[36]

Minnesota passed the first charter school law in the United States in 1991. As of 2015, Minnesota had 165 registered charter schools, with over 41,000 students attending. The first of these to be approved, Bluffview Montessori School in Winona, Minnesota, opened in 1992. The first charter to operate was City Academy in St. Paul. Some specialized Minnesota charter schools include the Metro Deaf School (1993), Community of Peace Academy (1995), and the Mainstreet School of Performing Arts (2004).[37]

As of December 2011 approximately 5,600 charter schools enrolled an estimated total of more than 2 million students nationwide.[38] The numbers equate to a 13% growth in students in just one year, while more than 400,000 students remain on charter school waitlists. Over 500 new charter schools opened their doors in the 2011–12 school year, an estimated increase of 200,000 students. This year marks the largest single-year increase ever recorded in terms of the number of additional students attending charter schools.[39][40]

The most radical experimentation with charter schools in the United States possibly occurred in New Orleans, Louisiana, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina (2005). As of 2009 the New Orleans Public Schools system was engaged in reforms aimed at decentralizing power away from the pre-Katrina public school board to individual charter school principals and boards, monitoring charter school performance by granting renewable, five-year operating contracts permitting the closure of those not succeeding, and parents the choice to enroll their children in almost any school in the district.[41] New Orleans is one of two cities in the United States of America where the majority of school students attend charter schools.[42] 78% of all New Orleans schoolchildren studied in charter schools during the 2011–12 school year.[43] As of May 2014, all but five of New Orleans' schools were charter schools.[44]

Unlike their public counterparts, laws governing charter schools vary greatly from state to state. The three states with the highest number of students enrolled in charter schools are California, Arizona, and Michigan.[45] These differences largely relate to what types of public agencies are permitted to authorize the creation of charter schools, whether or not and through what processes private schools can convert to charter schools, and what certification, if any, charter school teachers require.

In California, local school districts are the most frequent granters of school charters. If a local school district denies a charter application, or if the proposed charter school provides services not provided by the local school districts, a county board consisting of superintendents from state schools or the state board of education can grant a charter.[46] The Arizona State Board for Charter Schools grants charters in Arizona. Local school districts and the state board of education can also grant charters. In contrast, the creation of charter schools in Michigan can be authorized only by local school boards or by the governing school boards of state colleges and universities.[47]

Different states with charter school legislation have adopted widely different positions in regard to the conversion of private schools to charter schools. California, for example, does not allow the conversion of private schools into charter schools. Both Arizona and Michigan allow such conversions, but with different requirements. A private school wishing to convert to a charter school in Michigan, for example, must show that at least 25% of its student population is made up of new students. Legislation in Arizona stipulates that private schools that wish to become charter schools within that state must have admission policies that are fair and non-discriminatory. Also, while Michigan and California require teachers at charter schools to hold state certification, those in Arizona do not.

Charter schools were targeted as a major component of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002.[48] Specifically, the act specifies that students attending schools labeled as under-performing by state standards now have the option to transfer to a different school in the district, whether it is a state, private, or charter school. The act also suggested that if a failing school cannot show adequate yearly progress, it will be designated a charter school.

As of 2005 there were almost 100 charter schools in North Carolina, the limit passed by legislation in 1996.[49] The 1996 legislation dictates that there will be no more than five charter schools operating within one school district at any given time. It was passed in order to offer parents options in regard to their children and the school they attend, with most of the cost being covered by tax revenue. After the first several years of permitting charter schools in North Carolina, the authority to grant charters shifted from local boards of education to the State Board of Education. This can also be compared with several other states that have various powers that accept charter school applications.

There is strong demand for charter schools from the private sector.[50] Typically, charter schools operate as nonprofits. However, the buildings in which they operate are generally owned by private landlords. Accordingly, this asset class is generating interest from real-estate investors who are looking towards the development of new schools. State and local governments have also shown willingness to help with financing. Charter schools have grown in popularity over the recent past. In 2014–2015, 500 new charter schools opened in the country. As of 2015, 6,700 charter schools enroll approximately 2.9 million students in the United States.[51][52]

Cyber schools

Charter cyber schools operate like typical charter schools in that they are independently organized schools, but are conducted partly or entirely over the Internet. Proponents say this allows for much more flexibility compared with traditional schools.[53]

For 2000–2001, studies estimated that there are about 45,000 online K–12 students nationally.[54] Six years later, a study by Picciano and Seamon (2006) found that over 1 million students were involved.[54] These numbers increased to 6.7 million students in 2013.[54] A study by Watson, Murin, Vashaw, Gemin, and Rapp found that cyber charter schools are currently (as of 2014) operating in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.[54]

The increase of these online campuses has aroused controversy.[54] In November, 2015, researchers at the University of Washington, Stanford University, and the Mathematica Policy Research group published the first major study of online charter schools in the United States, the "National Study of Online Charter Schools". It found "significantly weaker academic performance" in mathematics and reading in such schools when compared to conventional ones. The study resulted from research carried out in 17 US states which had online charter schools. It concluded that keeping online pupils focused on their work was the biggest problem faced by online charter schools and that in mathematics the difference in attainment between online pupils and their conventionally-educated peers equated to the cyber pupils missing a whole academic year in school.[55]

Four states have adopted specific legislation tailored to cyber charter schools. One example is Arizona, which has about 3,500 students in cyber schools, about half of them cyber charter schools and the other half governed by traditional, brick-and-mortar public school districts. The cyber schools teach students from kindergarten to 12th grade, and the setting varies from being entirely online in one's home to spending all of the class time in a formal school building while learning over the Internet.

Cyber charter school diplomas have been unevenly valued by post-secondary institutions. Universities sometimes apply additional requirements or have cyber-charter quotas limiting the number of applicants. The US military also classifies non-traditional diplomas at a lower tier, although as of 2012 this could be bypassed by high ASVAB test scores.[54]

Charter schools and public schools

Charter schools have gradually become popular since the system was introduced in 1996. The United States Department of Education defined these institutions as "public schools that do not charge tuition fees established through a charter or agreement between the school and local district school board." Through said accord, the charter schools get more autonomy than conventional public schools, in exchange for the higher level of accountability.[56]

In 2014, New Orleans made headlines for becoming the first school district in the United States to become an all charter district. [57]

A 2017 policy statement from the National Education Association expressed its strong commitment to public schools. Charter schools are funded by taxpayers so there must be the same liability, transparency, safeguards, and impartiality as public schools. 44 American states along with the District of Columbia implement legislation on state charter schools. However, many states do not compel charters to abide by open meeting statutes as well as prerequisites on conflict of interest that pertain to school districts, boards, and employees.[58] The NEA was quoted as declaring that certain state laws, rules, and guidelines may still be relevant to charter schools. These institutions are not supervised by the state but by a board of directors. The establishment of charter schools was meant to promote competition among students and provide parents with more options for enrolling their children. Heightened competition can result in effective educational programs nationwide.[59]

Department of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos espoused "school choice" before accepting the position in President Donald Trump's administration. School choice refers to spending funds for public charter schools and some private schools. DeVos said in an interview on March 12, 2018, that charter schools can improve the long-established public school system. Betsy DeVos was a campaigner for the American Federation of Children.[60] The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools circulated a research study, “The Health of the Public School Charter Movement: A State by State Analysis.” This report pointed out data regarding the movement's condition along indicators of quality, progress, and innovation.

See also

| Library resources about Charter school |

- Bradley Foundation

- Charter School Growth Fund

- DreamBox (company)

- Broad Foundation

- Koch Family Foundations

- Walton Foundation

References

- "Why hedge funds love charter schools". Washington Post. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Sarah Knopp (2008). "Charter schools and the attack on public education". International Socialist Review (62). Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Weinberg, Lawrence D. (2007). Religious Charter Schools: Legalities and Practicalities. Charlotte, NC: IAP. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-60752-622-3.

- Brown, Emma (4 February 2015). "Are charter schools public or private?". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Charter Law Database | National Alliance for Public Charter Schools". www.publiccharters.org. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Ravitch, Diane (8 December 2016). "When Public Goes Private, as Trump Wants: What Happens?". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Tell, Shawgi (1 April 2016). Charter School Report Card. Charlotte, NC: IAP. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-68123-296-6.

- "Here's how our schools are funded – and we promise not to mention Gonski". ABC News. 30 May 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "WA's Independent Public Schools initiative to come under parliamentary microscope". ABC News. 26 February 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Action on Research and Innovation: The Future of Charter Schools in Alberta" (PDF). Government of Alberta. January 2011. p. 1. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Ritchie, Shawna (January 2010). "Innovation in Action: An Examination of Charter Schools in Alberta" (PDF). the West in Canada Research Series. CanadaWest Foundation. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- "A Primer on Charter Schools". The Fraser Institute. 10 December 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Charter Schools List" (PDF). Alberta Education. 4 December 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Charter Schools in Alberta". Alberta Education. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "School Act: Charter Schools Regulation" (PDF). Province of Alberts. March 2007. p. 8. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "What Pinochet Did for Chile". Hoover Institution. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Carnoy, Martin (August 1998). "National Voucher Plans in Chile and Sweden: Did Privatization Reforms Make for Better Education?". Comparative Education Review. 42 (3): 309–337. doi:10.1086/447510. JSTOR 1189163.

- "Chile's School Voucher System: Enabling Choice or Perpetuating Social Inequality?". New America. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Larrañaga, Osvaldo (2004). "Competencia y Participación Privada: La experiencia Chilena en Educación". Estudios Públicos. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jarroud, Marianela (11 August 2011). "Chilean student protests point to deep discontent". Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- Bgcenter. "Colombian Educational Systems". www.bgcenter.com. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Private education in Colombia". Just Landed. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Grant Maintained Schools Database". The National Digital Archive of Datasets. The National Archives. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- "Q&A: Academies and free schools". BBC News Online. 26 May 2010.

- "Germany: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Finanzen der Schulen – Schulen in freier Trägerschaft und Schulen des Gesundheitswesens" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt. 14 June 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "German Higher Education Entrance Qualification". Study in Germany for Free. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Two-thirds of Hong Kong's direct subsidy scheme schools raise fees". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Zealand, Education in New. "Partnership Schools | Kura Hourua (Charter Schools)". Education in New Zealand. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Elevar i grunnskolen, 1. oktober 2015". Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Fisman, Ray (15 July 2014). "Sweden's School Choice Disaster". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "The Swedish model". The Economist. 12 June 2008.

- Buonadonna, Paola (26 June 2008). "Free schools". BBC News Online.

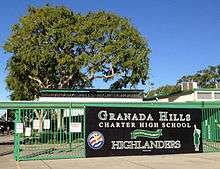

- DiMassa, Cara Mia. "Granada Hills Gets Charter OK." Los Angeles Times. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "50-State Comparison: Charter School Policies". www.ecs.org.

- Government Printing Office (2011). Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Barack Obama, 2009. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-16-088007-0.

- "Minnesota Charter Schools". 2015. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Zinsmeister, Karl. (Spring 2014). "From Promising to Proven: The charter school boom ahead". Philanthropy Magazine.

- National Center for Education Statistics (2016). "Charter School Fast Facts".

- Education Digest (2014). "Number and enrollment of public elementary and secondary schools, by school level, type, and charter and magnet".

- Vallas wants no return to old ways. The Times-Picayune (New Orleans). 25 July 2009.

- RSD looks at making charters pay rent, The Times-Picayune, 18 December 2009.

- Executive Summary, http://www.coweninstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/SPENO-20121.pdf Archived 23 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Rebecca Klein, Huffington Post, 30 May 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/05/30/new-orleans-traditional-public-schools_n_5414372.html

- Powers, Jeanne M. "Charter Schools." Encyclopedia of the Social and Cultural Foundations of Education. 2008. SAGE Publications. 5 December 2011.

- Premack, Eric. "Charter schools: California's education reform 'power tool.'(Special Section on Charter Schools)." Phi Delta Kappan 78.1 (1996): 60+. Academic OneFile. Web. 5 December 2011.

- Lacireno-Paquet, Natalie. "Moving Forward or Sliding Backward: The Evolution of Charter School Policies in Michigan and the District of Columbia." Educational policy (Los Altos, CA) 21. (2007): 202. Web. 5 December 2011. Educational policy (Los Altos, CA).

- US Department of Education (7 November 2004). "Questions and Answers on No Child Left Behind...Charter Schools".

- Knight, Meghan. "Cyber Charter Schools: An Analysis of North Carolina's Current Charter School Legislation." North Carolina journal of law . 6. (2005): 395. Web. 6 December 2011. http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/ncjl6.

- Sarah R. Cohodes; Elizabeth M. Setren; Christopher R. Walters; Joshua D. Angrist; Parag A. Pathak (October 2013). "Charter School Demand and Effectiveness" (PDF).

- Grant, Peter (13 October 2015). "Charter-School Movement Grows – for Real-Estate Investors: New niche develops as more charters open doors; some states help with financing". Real estate. The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- NCES, The Condition of Education – Charter School Enrollment, April 2016

- Pennsylvania Department of Education, Cyber Charter Schools, 2014

- Barkovich, David (2014). A Study of College Admission Officers' Attitudes and Perceptions About Cyber-Charter High School Applicants (doctoral dissertation). pp. 2–136 – via ProQuest.

Estimations of K–12 online learners in 2000-2001 placed the enrollment nationally at 40–50,000 students (Clark, 2000) while just a year later The Peak Group (2002) placed the number at 180,000.

- Coughlan, Sean (4 November 2015). "Online schools 'worse than traditional teachers'". BBC News Online. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- "Charter vs public school: What's the difference?". WTLV. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Greenblatt, Alan. "New Orleans District Moves To An All-Charter System". NPR. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Charter Schools". NEA. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "Charter Schools vs. Traditional Public Schools: Which One is Under-Performing?". PublicSchoolReview.com. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Brown, Elisha (12 March 2018). "Betsy DeVos Says Charter Schools Make Public Schools Better. Her Home State Shows That's Not True". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 4 June 2018.